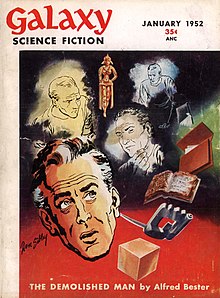

Cover of first edition (hardcover) | |

| Author | Alfred Bester |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Mark Reinsberg |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Shasta Publishers (first edition) |

Publication date | 1953 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | 250 |

| OCLC | 3638143 |

The Demolished Man is a science fiction novel by American writer Alfred Bester, which was the first Hugo Award winner in 1953. An inverted detective story, it was first serialized in three parts, beginning with the January 1952 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction,[1] followed by publication of the novel in 1953. The novel is dedicated to Galaxy's editor, H. L. Gold, who made suggestions during its writing. Bester's title was Demolition!, but Gold talked him out of it.

The Demolished Man is a science fiction police procedural set in a future where telepathy is common, although much of its effectiveness is derived from one individual having greater telepathic skill than another.

In the 24th century, telepaths—called Espers or "peepers"—are integrated into all levels of society. They are classed according to their abilities.

All Espers can telepathically communicate amongst themselves and the more powerful Espers can overwhelm their juniors. Telepathic ability is innate and inheritable but can remain latent and undetected in untrained persons. Once recognized, natural aptitude can be developed through instruction and exercise. There is a guild to improve Espers' telepathic skills, to set and enforce ethical conduct guidelines, and to increase the Esper population through intermarriage.

Some latent telepaths are undiscovered, or are aware of their abilities but refuse to submit to Guild rule. Some are ostracized as punishment for breaking the rules. One character in the story has suffered this fate for ten years, leaving him desperate for even vicarious contact with other telepaths.

Ben Reich is the paranoid, impetuous owner of Monarch Utilities & Resources, a commercial cartel that the Reich family has possessed for generations. Monarch Utilities & Resources is in danger of bankruptcy because of its chief rival, the D'Courtney Cartel, headed by the older Craye D'Courtney. Reich suffers recurring nightmares in which a "Man with No Face" persecutes him.

Desperate to end his suffering, Reich contacts D'Courtney and proposes a merger of their concerns but Reich's damaged psychological state causes him to misread D'Courtney's positive response as a refusal.[2] Frustrated and desperate, Reich determines to kill D'Courtney. The presence of "peepers" has prevented the commission of murder for more than seventy years so Reich devises an elaborate plan to ensure his freedom. If caught Reich will certainly face "Demolition", a terrible punishment described only at the end of the story.

Reich hires an Esper to "run interference" for him—hiding his murderous thoughts from any peepers present at the scene of the planned crime. Reich bribes Dr. Augustus ("Gus") Tate, a prominent peeper psychiatrist, and uses him to mentally steal information about D'Courtney's planned attendance at a party. To further conceal his intentions from telepaths, Reich visits a songwriter, Duffy Wygand, to teach him a jingle that makes his real thoughts hard to read.

From Monarch's research facility, Reich secures a small flash grenade which can disrupt a victim's perception of time by temporarily destroying the eyes' rhodopsin. He acquires an antique (20th-century) handgun from a pawn shop, making sure to have the bullets removed from the cartridges when he buys it. He knows how to replace the bullet in the handgun's ammunition with a gelatin capsule filled with water in order to eliminate ballistics evidence.

At the party, he influences the host to play a game of Sardines in total darkness. Reich executes his plan during the game but there is an unforeseen hitch: at the moment he shoots D'Courtney, D'Courtney's daughter Barbara witnesses the murder, struggles with Reich, grabs the gun, and runs away. She is later found suffering severe psychological shock that renders her catatonic and mute. Nobody but the party's hostess Maria knew Barbara was with her father. Reich recovers his composure, returns to the party and pretends to be lost. Just as he is about to leave, completing his getaway, a drop of blood from D'Courtney's body in the room above lands on him, and the party ends in chaos as the police are called.

A telepathic police detective, Lincoln Powell, is assigned to the case. As telepathically gathered evidence is legally inadmissible in court, but can be used to guide an investigation, the detective is obliged to assemble the murder case with traditional police procedures and to establish motive, opportunity, and method. The detective manages to read Reich's thoughts, sees that he is the murderer, and asks him to surrender. Reich refuses, relishing the thrill of the hunt to come.

Both sides center on finding and questioning (or, in Reich's case, silencing) Barbara D'Courtney. Although Reich finds her first, he is unable to kill her before Powell rescues her. The pursuit traverses the Solar System as Reich escapes the police and a series of mysterious assassination attempts. Others are attacked also: during Powell's attempt to interrogate the pawnbroker from whom Reich bought the gun, an unknown person attacks the pawnshop with a "harmonic gun" which kills by resonant sonic vibration. Reich tries but fails to murder Hassop, his own chief of communications (to try to prevent him from assisting the police with his knowledge of the corporate codes), and Powell succeeds in abducting Hassop.

Powell has already established opportunity and, eventually, method through discovery of a tiny fragment of gelatin in the body. Just as Powell believes that he has wrapped the case up entirely, the interrogation of Hassop yields disturbing results: D'Courtney had accepted the merger proposal. That dashes Powell's case; as he remarks, no court in the Solar System would believe Reich murdered D'Courtney when D'Courtney was needed alive for the merger (which would save Reich and give him all the power and wealth he dreamed of) to succeed.

Reich's tortured mental state is unknown to Reich himself, so Powell does not suspect that the motive for the murder was something other than financial. After more attempts on his life, and more dreams of the "Man with No Face", Reich attempts to kill Powell. Powell easily disarms him and then reads his mind. Suddenly Powell recognizes that the forces behind Reich's crime are greater than anticipated. He asks the help of every Esper in attempting to arrest Reich, channeling their collective mental energy through Powell in the dangerous telepathic procedure called the "Mass Cathexis Measure". He justifies this by claiming that Reich is an embryonic megalomaniac who will remake society in his own twisted image if not stopped.

Powell uses the power to construct a solipsistic fantasy for Reich to experience. One by one, he removes elements of reality, beginning with the stars in the sky, until Reich is left believing that he is the only real being in a world constructed around him, as a game. Finally Reich is left facing the "Man with No Face", who is both himself and Craye D'Courtney.

Reich is revealed to be the natural son of Craye D'Courtney, from an affair with Reich's mother — Reich's hatred of him was probably due to a latent, telepathic knowledge of that fact. Reich's knowledge is not explicitly stated but Barbara D'Courtney, whom Powell discovers to be Reich's half-sister, is herself revealed to be a peeper. The assassination attempts on Reich were carried out by Reich himself as a result of his disturbed state. Once arrested and convicted, Reich is sentenced to the dreaded Demolition— the stripping away of his memories and the upper layers of his personality, emptying his mind for re-education. This 24th-century society uses psychological demolition because it recognizes the social value of strong personalities able to successfully defy the law, seeking the salvaging of positive traits while ridding the person of the evil consciousness of the criminal.

Reviewer Groff Conklin characterized The Demolished Man as "a magnificent novel... as fascinating a study of character as I have ever read".[3] Boucher and McComas praised the novel as "a taut, surrealistic melodrama [and] a masterful compounding of science and detective fiction", singling out Bester's depiction of a "ruthless and money-mad [society] that is dominated and being subtly reshaped by telepaths" as particularly accomplished.[4] Imagination reviewer Mark Reinsberg received the novel favorably, citing its "brilliant depictions of future civilization and 24th century social life".[5]

After criticizing unrealistic science fiction, Carl Sagan in 1978 listed The Demolished Man as among stories "that are so tautly constructed, so rich in the accommodating details of an unfamiliar society that they sweep me along before I have even a chance to be critical".[6] For a 1996 reprint, author Harry Harrison wrote an introduction in which he called it "a first novel that was, and still is, one of the classics".[7] Richard Beard described the book as "full of vigorous action", saying, "the ripping pace of the book becomes part of what it's about".[8]

In an SF Site Featured Review, Todd Richmond wrote that the book is "a complicated game of manoeuvering, evasion, and deception, as Reich and Polwell [sic] square off against one another", adding:

The game is a very interesting one, because while Reich is a very rich man and has considerable resources, Polwell [sic] has an entire network of peepers to help him gather information and obtain evidence... The best part of Bester's story is its timelessness... There are few references to outlandish or dated technology (with the exception of a punch card computer!) or outrageous social practices or fashions. While Bester's future isn't utopia, neither is it a post-apocalyptic nightmare... Bester extrapolates his view of the 50s forward in time, recognizing that while things like technology will change, basic human nature will not. The Demolished Man is a welcome change for those tired of modern trilogies and series.[9]

In his "Books" column for F&SF, Damon Knight selected Bester's novel as one of the 10 best sf books of the 1950s.[10]

The Demolished Man won the 1953 Hugo Award for Best Novel and placed second for the year's International Fantasy Award for fiction.[11] The Orion Publishing Group chose the novel as its fourteenth selection for its series SF Masterworks in 1999.

The novel has several other characters who only marginally participate in the plot:

Bester played with typographic symbols when constructing various characters' names. This gave "Wyg&" for "Wygand", "@kins" for "Atkins", and "¼Maine" for "Quartermaine". He also used overtyping to strike out the "2" in Jerry Church's label of "Esper 2", to show that he has been expelled from the Esper community.

Jo Walton has said that The Demolished Man is shaped by Freudian psychology, comparing it to The Last Battle's relation to Christianity, and emphasizing that the resolution of the plot only makes sense in a Freudian context: Reich's hatred of D'Courtney is motivated by oedipal feelings.[13] Writer Richard Beard thought the Freudian aspects dubious: "Not all his future projections have worn so well. Reich's motives are stiffly dependent on Freudian theory, but most glaringly Bester fails to predict any type of feminism. The words girl and pretty always come as a pair."[8]

In 1959, novelist Thomas Pynchon applied for a Ford Foundation Fellowship to work with an opera company, proposing to write, among other possibilities, an adaptation of The Demolished Man. The application was turned down.[citation needed]

Since reading the novel as a young man, director Brian De Palma has considered adapting it for film.[14][15] Lack of financing has long since kept the film unproduced.

The Demolished Man was adapted for German radio by RIAS Berlin in 1973 under the title Demolition. It was the first radio drama recorded with the dummy head recording method.[16]

The Demolished Man was adapted for Norwegian NRK Radio in 1981 under the title Demolisjon.[17]

Donald Fagen of the band Steely Dan said of their hit song "Deacon Blues":

The concept of the "expanding man" that opens the song may have been inspired by Alfred Bester's The Demolished Man. Walter and I were major sci-fi fans. The guy in the song imagines himself ascending to the levels of evolution, "expanding" his mind, his spiritual possibilities, and his options in life.[18]

The TV series Babylon 5 features an organization similar to the telepathic guild, called Psi Corps. A character named Alfred Bester is a prominent member for the organization. Various other themes of the story are present in the episode "Passing Through Gethsemane", in particular a version of Demolition referred to as "death of personality".