Writing about women

- This Wikipedia essay was first published on February 26, 2015 and written by 53 other editors. Essays are not project guidelines, policies, or part of the Wikipedia's Manual of Style. They may or may not have broad support among the Wikipedia commuity. You may edit this essay if you wish, but please do it at the original essay page.

When writing about women on Wikipedia, make sure articles do not use sexist language, perpetuate sexist stereotypes or otherwise demonstrate a prejudice against women.

As of June 2019, 16.7% of editors on the English Wikipedia who have declared a gender say they are female.[1] The gender disparity, together with the need for reliable sources, contributes to the gender imbalance of our content; as of March 2020, only 18.27% of our biographies are about women.[2] This page may help to identify the subtle and more obvious ways in which titles, language, images, and linking practices can discriminate against women.

Data

Among editors of the English Wikipedia who specify a gender in their preferences, 115,941 (16.7%) were female and 576,106 male as of 13 June 2019.[1][a]

As of 10 March 2020, the English Wikipedia hosted 1,693,225 biographies, 291,649 (18.27%) of which were about women.[2] As a result of sourcing issues, almost all biographies before 1900 are of men.[5]

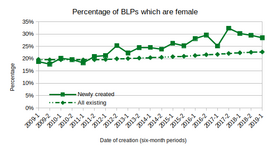

In 2009 the percentage of biographies of living persons (BLPs) about women was under 20%, but the numbers have been rising steadily since 2012–2013. As of 5 May 2019, the English Wikipedia hosted 906,720 BLPs, according to figures produced by Andrew Gray using Wikidata. Wikidata identified 697,402 of these as male and 205,117 as female.[b] The percentages of those that specified a gender were 77.06% male and 22.67% female; 0.27% had another gender.[6]

Male is not the default

Avoid language that makes female the Other to a male Self.[7]

Researchers have found that Wikipedia articles about women are more likely to contain words such as woman, female and lady, than articles about men are to contain man, male, or gentleman. This suggests that editors write with an assumption of male as the default gender and expect that individuals are assumed to be male unless otherwise stated.[8][9] This tendency is easily countered by removing unnecessary specification of sex or gender. Avoid labelling a Margaret Atwood as a female author or Margaret Thatcher as female politician except in specific sentences or paragraphs in which their gender is explicitly relevant.

Categories are equally susceptible to asymmetric treatment of genders. In April 2013 several media stories noted that editors of the English Wikipedia had begun moving women from Category:American novelists to Category:American women novelists, while leaving men in the main category.[10][11] Labelling a male author as a "writer" and a female author as a "woman writer" presents women as marked—requiring an adjective to differentiate them from a male default.[12] Symmetry of categories has improved since 2013, but where editors encounter an imbalance they should correct it by moving male subjects to explicitly male categories (for as long as the current consensus regarding gendered categories holds).

Use surnames

In most situations, avoid referring to a woman by her first name, which can serve to infantilize her.[c] As a rule, after the initial introduction ("Susan Smith is an Australian anthropologist"), refer to women by their surnames ("Smith is the author of ..."). Here is an example of an editor correcting the inappropriate use of a woman's first name.

First names are sometimes needed for clarity. For example, when writing about a family with the same surname, after the initial introductions they can all be referred to by first names. A first name might also be used when a surname is long and double-barreled, and its repetition would be awkward to read and write. When a decision is made to use first names for editorial reasons, use them for both women and men.

Writing the lead

Importance of the lead

According to Graells-Garrido et al. (2015), the lead is a "good proxy for any potential biases expressed by Wikipedia contributors".[14] The lead may be the only part of an article that is read—especially on mobile devices—so pay close attention to how women are described there. Again, giving women "marked" treatment can convey subtle assumptions to readers.

First woman

An article about a woman does not pass the Finkbeiner test if it mentions that "she's the first woman to ...." The test raises awareness of how gender becomes more important than a person's achievements.

Avoid language that places being a woman ahead of the subject's achievements. Opening the lead with "Smith was the first woman to do X", or "Smith was the first female X", immediately defines her in terms of men who have done the same thing, and it can inadvertently imply: "She may not have been a very good X, but at least she was the first woman."[15] When prioritizing that the subject is a "first woman", make sure it really is the only notable thing about her. Otherwise start with her own position or accomplishments, and mention the fact that she is a woman afterwards if it is notable.

For example, as of 10 March 2015, Wikipedia described Russian chemist Anna Volkova solely in terms of four first-woman benchmarks.[16] But the biographies of Indira Gandhi and Margaret Thatcher, as of the same date, began with the positions they held, and only then said that they were the first or only women to have held them.[17]

Infoboxes

Infoboxes are an important source of metadata (see DBpedia) and a source of discrimination against women. For example, the word spouse is more likely to appear in a woman's infobox than in a man's.[18]

When writing about a woman who works or has worked as, but is not primarily known for being a model, avoid ((Infobox model)). It includes parameters for hair and eye colour and previously contained parameters for bust, hip, waist size and weight. The latter were removed in March 2016 following this discussion. If you add an infobox (they are not required), consider using ((Infobox person)) instead.

Relationships

Defining women by their relationships

Wherever possible, avoid defining a notable woman, particularly in the title or first sentence, in terms of her relationships (wife/mother/daughter of). Do not begin a biography with: "Susan Smith is the daughter of historian Frank Smith and wife of actor John Jones. She is known for her work on game theory." An example of the kind of title the Wikipedia community has rejected is Sarah Brown (wife of Gordon Brown).

Researchers have found that Wikipedia articles about women are more likely to discuss their family, romantic relationships, and sexuality, while articles about men are more likely to contain words about cognitive processes and work. This suggests that Wikipedia articles are objectifying women.[19][d] Women's biographies mention marriage and divorce more often than men's biographies do.[21] Biographies that refer to the subject's divorce are 4.4 times more likely to be about a woman on the English Wikipedia. The figures are similar on the German, Russian, Spanish, Italian and French Wikipedias.[e]

[T]he greater frequency and burstiness of words related to cognitive mechanisms in men, as well as the more frequent words related to sexuality in women, may indicate a tendency to objectify women in Wikipedia. ... [M]en are more frequently described with words related to their cognitive processes, while women are more frequently described with words related to sexuality. In the full biography text, the cognitive processes and work concerns categories are more bursty in men biographies, meaning that those aspects of men's lives are more important than others at the individual level."[15]

A woman's relationships are inevitably discussed prominently when essential to her notability, but try to focus on her own notable roles or accomplishments first. For example, consider starting articles about women who were First Lady of the United States, which is a significant role, with "served as First Lady of the United States from [year] to [year]", followed by a brief summary of her achievements, rather than "is/was the wife of President X".

Marriage

When discussing a woman who is married to a man, write "A is married to B" instead of "A is the wife of B", which casts the male as possessor. Avoid the expression "man and wife", which generalizes the husband and marks the wife. Do not refer to a woman as Mrs. John Smith; when using an old citation that does this, try to find and use the woman's own name, as in: "Susan Smith (cited as Mrs. J. Smith)".

When introducing a woman as the parent of an article subject, avoid the common construction, "Smith was born in 1960 to John Smith and his wife, Susan." Consider whether there is an editorial reason to begin with the father's name. If not, try "Susan Jones and her husband, John Smith" or, if the woman has taken her husband's name, "Susan Smith, née Jones, and her husband, John", or "Susan and John Smith". Where there are several examples of "X and spouse" in an article, alternate the order of male and female names.

Internal links

The focus on relationships in articles about women affects internal linking and therefore search-engine results. One study found that women on Wikipedia are more linked to men than men are linked to women. When writing an article about a woman, if you include an internal link to an article about a man, consider visiting the latter to check that it includes reciprocal information about the relationship; if it merits mention in the woman's article, it is likely germane to his. Failure to mention the relationship in both can affect search algorithms in a way that discriminates against women.[f]

Language

Gender-neutral language

Use gender-neutral nouns when describing professions and positions: actor, author, aviator, bartender, chair, comedian, firefighter, flight attendant, hero, poet, police officer. Avoid adding gender (female pilot, male nurse) unless the topic requires it.

Do not refer to human beings as a group as man or mankind. Sentences such as "man has difficulty in childbirth" illustrate that these are not inclusive generic terms.[24] Depending on the context, use humanity, humankind, human beings, women and men, or men and women.

Word order

Some will set the cart before the horse, as thus: "My mother and my father are both at home", even as though the goodman of the house did wear no breeches, or that the gray mare were the better horse. ... in speaking at the least let us keep a natural order and set the man before the woman for manners' sake.

— Thomas Wilson (Arte of Rhetorique, 1553).[25]

The order in which groups are introduced—man and woman, male and female, Mr. and Mrs., husband and wife, brother and sister, ladies and gentlemen—has implications for their status, so consider alternating the order as you write.[26]

Girls, ladies

Do not refer to adult women as girls or ladies,[27] unless using common expressions, proper nouns, or titles that cannot be avoided (e.g., leading lady, lady-in-waiting, ladies' singles, Ladies' Gaelic Football Association, First Lady). The inappropriate use of ladies can be seen in Miss Universe 1956, which on 12 March 2015 said there had been "30 young ladies in the competition", and in Mixer dance, which discussed "the different numbers of men and ladies".[28]

Pronouns: Avoid generic he

The use of the generic he (masculine pronouns such as he, him, his) is increasingly avoided in sentences that might refer to women and men or girls and boys.[29] Instead of "each student must hand in his assignment", try one of the following.

- Rewrite the sentence in the plural: "students must hand in their assignments."

- Use feminine pronouns: "each student must hand in her assignment." This is often done to signal the writer's rejection of the generic he,[30] the "linguistic equivalent of affirmative action".[31] See WP:HER.

- Alternate between the masculine and feminine in different paragraphs or sections.[31]

- Rewrite the sentence to remove the pronoun: "student assignments must be handed in."

- Write out the alternatives—he or she, him or her, his or her; him/her, his/her.

- Use a composite form for the nominative—s/he or (s)he.[32]

- Use the singular they: "each student must hand in their assignment". It is most often used with someone, anyone, everyone, no one.[33]

| Nominative (subject) |

Accusative (object) |

Dependent possessive pronoun | Independent possessive pronoun | Reflexive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| When I tell someone a joke, they laugh. | When I greet a friend, I hug them. | When someone leaves the library, their book is stamped. | A friend lets me borrow theirs. | Each person drives there themselves (or, nonstandard, themself). |

Sources

Avoid using openly sexist sources unless there is a strong editorial reason to use them. For example, do not use pornographic or men's websites and magazines (such as AskMen, Playboy, and Maxim) in the biographies of female actors. Be careful not to include trivia that appeals predominantly to men. A source need not be overtly sexist to set a bad example. For example, most women are underrepresented in certain institutions that are slow to change. Often such institutions can be fine to use as a source for men, but for women, not so much.

Images

Avoid images that objectify women. In particular, do not use pornography images in articles that are not about pornography. Wikipedia:Manual of Style/Images states that "photographs taken in a pornography context would normally be inappropriate for articles about human anatomy".

Except when the topic is necessarily tied to it (examples: downblouse and upskirt), avoid examples of male-gaze imagery, where women are presented as objects of heterosexual male appreciation.[34] When adding an image of part of a woman's body, consider cropping the image to focus on that body part.

When illustrating articles about women's health and bodies, use authoritative medical images wherever possible.

Medical issues

When writing about women's health, make sure medical claims are sourced according to the medical sourcing guideline, WP:MEDRS. As a rule this means avoiding primary sources, which in this context refers to studies in which the authors participated. Rely instead on peer-reviewed secondary sources that offer an overview of several studies. Secondary sources acceptable for medical claims include review articles (systematic reviews and literature reviews), meta-analyses and medical guidelines.

To find these sources, enter the search term (e.g., "mammography") into the National Institutes of Health search engine PubMed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/, and select "reviews" from the "article types" menu. A search for review articles on "mammography" brings up this list. Or select "customize", then the article type (e.g., meta-analysis or guideline). To check an article type (e.g., P. M. Otto, C. B. Blecher, "Controversies surrounding screening mammography", Missouri Medicine, 111(5), Sep–Oct 2014), open the drop-down menu "Publication type" under the abstract. In this case, the classification is "Review". When in doubt, ask for help at Wikipedia talk:WikiProject Medicine.

See also

- WP:GGTF, Gender gap task force

- WP:HER, an essay encouraging the use of feminine pronouns

- Wikipedia:WikiProject Women in Red, addressing the content gender gap

- Wikipedia:WikiProject Women in Red/Essays/Writing women into the encyclopedia

Notes

- ^ Women are thought to comprise between 8.5%[3] and 16.1%[4] of editors on the English Wikipedia.

- ^ Another 2,464 had some other value, 1,220 had none, and 517 were not on Wikidata.

- ^ Milman (2014): "More stylistic choices by journalists further contributed to the paternalistic construction of the [Mothers' movement] protesters as girls and their subjugation to father-like figures ...[T]he press ... infantilized the protesters by referring to them as "the girls" ... and by using their first names rather than referring to them by their family names as is the custom when writing about political figures ..."[13]

- ^ Graells-Garrido, Lalmas and Menczer (2015): "Sex-related content is more frequent in women biographies than men's, while cognition-related content is more highlighted in men biographies than women's."[20]

- ^ Wagner et al. (2015): "[I]n the English Wikipedia an article about a notable person that mentions that the person is divorced is 4.4 times more likely to be about a woman rather than a man. We observe similar results in all six language editions. For example, in the German Wikipedia an article that mentions that a person is divorced is 4.7 times more likely about a woman, in the Russian Wikipedia its 4.8 times more likely about a woman and in the Spanish, Italian and French Wikipedia it is 4.2 times more likely about a women. This example shows that a lexical bias is indeed present on Wikipedia and can be observed consistently across different language editions. This result is in line with (Bamman and Smith 2014) who also observed that in the English Wikipedia biographies of women disproportionately focus on marriage and divorce compared to those of men."[22]

- ^ Wagner et al. (2015): "[W]omen on Wikipedia tend to be more linked to men than vice versa, which can put women at a disadvantage in terms of—for example—visibility or reachability on Wikipedia. In addition, we find that women's romantic relationships and family-related issues are much more frequently discussed in their Wikipedia articles than in articles on men. This suggests differences in how the Wikipedia community conceptualizes notable men and women. Because modern search and recommendation algorithms exploit both structural and lexical information on Wikipedia, women might be discriminated when it comes to ranking articles about notable people. To reduce such effects, the editor community could pay particular attention to the gender balance of links included in articles about men and women, and could adopt a more gender-balanced vocabulary when writing articles about notable people."[23]

References

- ^ a b "Overall ratio of declared genders". quarry.wmflabs.org. 13 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Gender by language: All time, as of Mar '20". Wikidata Human Gender Indicators (WHGI).

- ^ WMF 2011, p. 2.

- ^ Hill & Shaw 2013.

- ^ Graells-Garrido, Lalmas & Menczer 2015.

- ^ Gray, Andrew (6 May 2019). "Gender and deletion on Wikipedia". generalist.org.uk.

- ^ Jule 2008, p. 13ff.

- ^ Wagner et al. 2015.

- ^ "Computational Linguistics Reveals How Wikipedia Articles Are Biased Against Women", MIT Technology Review, 2 February 2015.Titlow, John Paul (2 February 2015). "More Like Dude-ipedia: Study Shows Wikipedia's Sexist Bias", Fast Company.

- ^ Amanda Filipacchi (24 April 2013). "Wikipedia's Sexism Toward Female Novelists". The New York Times.

- ^ Alison Flood (25 April 2013). "Wikipedia bumps women from 'American novelists' category". The Guardian.

- ^ For marked and unmarked, see Deborah Tannen, "Marked Women, Unmarked Men", The New York Times Magazine, 20 June 1993.

- ^ Milman 2014, 73.

- ^ Graells-Garrido, Lalmas & Menczer 2015, p. 3.

- ^ a b Graells-Garrido, Lalmas & Menczer 2015, p. 8.

- ^ Anna Volkova, en.wikipedia.org, accessed 10 March 2015.

- ^ Indira Gandhi, Margaret Thatcher, en.wikipedia.org, accessed 10 March 2015.

- ^ Graells-Garrido, Lalmas & Menczer 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Graells-Garrido, Lalmas & Menczer 2015, pp. 2, 5–6, 8.

- ^ Graells-Garrido, Lalmas & Menczer 2015, p. 2.

- ^ Bamman & Smith 2014, p. 369.

- ^ Wagner et al. 2015, p. 460.

- ^ Wagner et al. 2015, p. 9.

- ^ Jule 2008, 14.

- ^ Wilson 1994, p. 193.

- ^ APA 2009, pp. 72–73; Hegarty 2014, pp. 69.

- ^ Eckert & McConnell-Ginet 2003, pp. 38–39; Lakoff 2004, 52–56; Holmes 2004, 151–157; Holmes 2000, pp. 143–155

- ^ "Miss Universe 1956" and Mixer dance, en.wikipedia.org, accessed 12 March 2015.

- ^ Huddleston & Pullum 2002, p. 492.

- ^ McConnell-Ginet 2014, p. 33; Adami 2009, pp. 297–298.

Wilder, Charly (5 July 2013). "Ladies First: German Universities Edit Out Gender Bias", Der Spiegel.

- ^ a b Huddleston & Pullum 2002, p. 493.

- ^ Huddleston & Pullum 2002, p. 493; Adami 2009, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Huddleston & Pullum 2002, 493; for a history of "singular they", see Bodine 1975, p. 131ff. Also see Whitman 2010.

- ^ "Male gaze", Geek Feminism Wiki.

Works cited

- Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th edition. American Psychological Association. 2009.

- "Wikipedia Editors' Survey" (PDF). Wikimedia. Wikimedia Foundation. April 2011.

- Adami, Elisabetta (2009). "To each reader his, their, or her pronoun". In Renouf, Antoinette; Kehoe, Andrew (eds.). Corpus Linguistics: Refinements and Reassessments. Rodopi. pp. 281–307.

- Bamman, David; Smith, Noel (2014). "Unsupervised Discovery of Biographical Structure from Text" (PDF). Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 2: 363–376. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00189. S2CID 10896312.

- Bodine, Ann (1975). "Androcentrism in prescriptive grammar: singular 'they,' sex-indefinite 'he,' and 'he or she'". Language in Society. 4 (2): 129–146. doi:10.1017/S0047404500004607. JSTOR 4166805. S2CID 146362006.

- Eckert, Penelope; McConnell-Ginet, Sally (2003). Language and Gender. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Graells-Garrido, Eduardo; Lalmas, Mounia; Menczer, Filippo (2015). "First Women, Second Sex: Gender Bias in Wikipedia". Proceedings of the 26th ACM Conference on Hypertext & Social Media - HT '15. New York: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 165–174. arXiv:1502.02341. doi:10.1145/2700171.2791036. ISBN 9781450333955. S2CID 1082360.

- Hegarty, Peter (2014). "Ladies and gentlemen: Word order and gender in English". In Corbett, Greville G. (ed.). The Expression of Gender. Walter de Gruyter.

- Hill, Benjamin Mako; Shaw, Aaron (2013). "The Wikipedia Gender Gap Revisited: Characterizing Survey Response Bias with Propensity Score Estimation". PLOS ONE. 8 (6): e65782. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...865782H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065782. PMC 3694126. PMID 23840366.

- Holmes, Janet (2004). "Power, Ladies and Linguistic Politeness". In Bucholtz, Mary (ed.). Language and Woman's Place: Text and Commentaries. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Holmes, Janet (2000). "Ladies and gentlemen: corpus analysis and linguistic sexism". In Mair, Christine; Hundt, Marianne (eds.). Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory. Freiburg im Breisgau: 20th International Conference on English Language Research on Computerized Corpora, 1999. pp. 143–155.

- Huddleston, Rodney; Pullum, Geoffrey K. (2002). The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jule, Allyson (2008). A Beginner's Guide to Language and Gender. Multilingual Matters.

- Lakoff, Robin Tolmach (2004) [1975]. Bucholtz, Mary (ed.). Language and Woman's Place: Text and Commentaries. New York: Oxford University Press.

- McConnell-Ginet, Sally (2014). "Gender and its relation to sex: The myth of 'natural' gender". In Corbett, Greville G. (ed.). The Expression of Gender. Walter de Gruyter.

- Milman, Noa (2014). "Mothers, Mizrahi, and Poor: Contentious Media Framings of Mothers' Movements". In Woehrle, Lynne M. (ed.). Intersectionality and Social Change. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. pp. 53–82.

- Wagner, Claudia; Garcia, David; Jadidi, Mohsen; Strohmaier, Markus (2015). "It's a Man's Wikipedia? Assessing Gender Inequality in an Online Encyclopedia". Proceedings of the Ninth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media: 454–463. arXiv:1501.06307v1.

- Whitman, Neal (4 March 2010). "Do's and Don'ts for Singular 'They'". vocabulary.com.

- Wilson, Thomas (1994) [1553]. Medine, Peter E. (ed.). The Art of Rhetoric. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Further reading

General

- User:Tony1/How to improve your writing

- Dines, Gail (2 December 2014). "Growing Up in a Pornified Culture", TEDx (discusses sexualized images).

- Klein, Maximilian, et al. (17 August 2016). "Monitoring the Gender Gap with Wikidata Human Gender Indicators", Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Open Collaboration.

- Peters, Mark (30 March 2017). "The hidden sexism in workplace language", BBC.

- Safire, William (18 March 2007). "Language: Woman vs. female", The New York Times (discusses using woman instead of female to modify nouns, as in "woman doctor").

- Shariatmadari, David (27 January 2016). "Eight words that reveal the sexism at the heart of the English language". The Guardian.

Books, papers

- (chronological)

- Lakoff, Robin (April 1973). "Language and women's place". Language in Society, 2(1), 45–80.

- Lakoff, Robin (1975). Language and Women's Place. New York: Harper & Row.

- Miller, Casey and Swift, Kate (1976). Words and Women: New Language in New Times. Anchor Press/Doubleday.

- Spender, Dale (1980). Man Made Language, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Miller, Casey and Swift, Kate (1980). The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing for Writers, Editors and Speakers. New York: Lippincott and Crowell.

- McConnell-Ginet, Sally (1984). "The origins of sexist language in discourse", in S. J. White and V. Teller (eds.). Discourse and Reading in Linguistics. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. New York: The New York Academy of Sciences, 123–135.

- Cameron, Deborah (1985). Feminism and Linguistic Theory. London: Routledge; revised 2nd edition, 1992.

- Frank, Francine Harriet and Treichler, Paula A. (1989). Language, Gender, and Professional Writing. New York: Modern Language Association of America.

- Cameron, Deborah (ed.) (1990). The Feminist Critique of Language: A Reader. London and New York: Routledge.

- Penelope, Julia (1990). Speaking Freely: Unlearning the Lies of the Fathers' Tongues, New York: Pergamon Press.

- Tannen, Deborah (1990). You Just Don't Understand: Women and Men in Conversation, New York: William Morrow.

- Eckert, Penelope and McConnell-Ginet, Sally (2003). Language and Gender, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Curzon, Anne (2003). Gender Shifts in the History of English, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lakoff, Robin (2004). Language and Woman's Place (original text), in Robin Lakoff, Mary Bucholtz (ed.), Language and Woman's Place: Text and Commentaries. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ehrlich, Susan, Meyerhoff, Miriam, [and [Janet Holmes (linguist)|Holmes Janet]] (eds.) (2005). The Handbook of Language, Gender, and Sexuality, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2nd edition, 2014.

- Jule, Allyson (2008). A Beginner's Guide to Language and Gender, Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Corbett, Greville G. (ed.) (2014). The Expression of Gender. Walter de Gruyter.

Discuss this story

There looks to be a gross error here. The ref at note 2 takes you to: 62 English 1767980 329746 18.65 - rank, language, all bios, female, %. This is around the figure I'm used to, and the 329746 is WAAAY higher than the 291,649 in the essay. I don't believe it was much different in March. The % looks ok though.[Actually this movement since March seems ok] As a long discussion at WiR showed, you can't understand gender ratios in WP BLPs without allowing for the massive distorting effect of the vast number of sports bios we have, the great majority male. Exclude all sports people, and the female BLP % is around 30%, which is not far away from the %s in many easily countable always-notable types of people, such as national elected politicians, heads of quoted businesses, fellows of national science academies etc etc. Johnbod (talk) 03:45, 1 December 2020 (UTC)[reply]