Front façade of the museum | |

Location in Oxford | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | 1683 |

|---|---|

| Location | Beaumont Street, Oxford, England |

| Coordinates | 51°45′19″N 1°15′36″W / 51.7554°N 1.2600°W |

| Type | University Museum of Art and Archaeology |

| Visitors | 930,669 (2019)[1] |

| Director | Alexander Sturgis |

| Website | www |

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology (/æʃˈmoʊliən, ˌæʃməˈliːən/)[2] on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum.[3] Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University of Oxford in 1677. It is also the world's second university museum, after the establishment of the Kunstmuseum Basel in 1661 by the University of Basel.[4]

The present building was built between 1841 and 1845. The museum reopened in 2009 after a major redevelopment, and in November 2011, new galleries focusing on Egypt and Nubia were unveiled. In May 2016, the museum also opened redisplayed galleries of 19th-century art.

History

[edit]Broad Street

[edit]The museum opened on 24 May 1683,[5] with naturalist Robert Plot as the first keeper. The building on Broad Street (later known as the Old Ashmolean) is sometimes attributed to Sir Christopher Wren or Thomas Wood.[6] Elias Ashmole had acquired the collection from the gardeners, travellers, and collectors John Tradescant the Elder and his son, John Tradescant the Younger. It included antique coins, books, engravings, geological specimens, and zoological specimens—one of which was the stuffed body of the last dodo ever seen in Europe; but by 1755 the stuffed dodo was so moth-eaten that it was destroyed, except for its head and one claw.[7]

Beaumont Street

[edit]

The present building dates from 1841 to 1845. It was designed as the University Galleries by Charles Cockerell[8] in a classical style and stands on Beaumont Street. One wing of the building is occupied by the Taylor Institution, the modern languages faculty of the university, standing on the corner of Beaumont Street and St Giles' Street. This wing of the building was also designed by Charles Cockerell, using the Ionic order of Greek architecture.[9]

Sir Arthur Evans, who was appointed keeper in 1884 and retired in 1908, is largely responsible for the current museum.[10] Evans found that the keeper and the vice-chancellor (Benjamin Jowett) had managed to lose half of the Ashmole collection and had converted the original building into the Examination Rooms. Charles Drury Edward Fortnum had offered to donate his personal collection of antiques on condition that the museum was put on a sound footing.[11] A donation of £10,000 from Fortnum (£1.44 million as of 2024) enabled Evans to build an extension to the University Galleries and move the Ashmolean collection there in 1894. In 1908, the Ashmolean and the University Galleries were combined as the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology.[12] The museum became a depository for some of the important archaeological finds from Evans' excavations in Crete.[citation needed]

After the various specimens had been moved into new museums, the "Old Ashmolean" building was used as office space for the Oxford English Dictionary. Since 1924, the building has been established as the Museum of the History of Science, with exhibitions including the scientific instruments given to Oxford University by Lewis Evans, amongst them the world's largest collection of astrolabes.[13]

Charles Buller Heberden left £1,000 (£56,000 as of 2024) to the university in 1921, which was used for the Coin Room at the museum.[14]

In 2012, the Ashmolean was awarded a grant of $1.1m by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to establish the University Engagement Programme or UEP. The programme employs three teaching curators and a programme director to develop the use of the museum's collections in the teaching and research of the university.[15]

Renovations

[edit]

The interior of the Ashmolean has been extensively modernised in recent years and now includes a restaurant and large gift shop.[16]

In 2000, the Chinese Picture Gallery, designed by van Heyningen and Haward Architects, opened at the entrance of the Ashmolean and is partly integrated into the structure. It was inserted into a lightwell in the Grade 1 listed building, and was designed to support future construction from its roof. Apart from the original Cockerell spaces, this gallery was the only part of the museum retained in the rebuilding. The gallery houses the Ashmolean's own collection and is also used from time to time for the display of loan exhibitions and works by contemporary Chinese artists. It is the only museum gallery in Britain devoted to Chinese paintings.[17]

The Bodleian Art, Archaeology and Ancient World Library, incorporating the older library collections of the Ashmolean, opened in 2001 and has allowed an expansion of the book collection, which concentrates on classical civilization, archaeology and art history.[18]

Between 2006 and 2009, the museum was expanded to the designs of architect Rick Mather and the exhibition design company Metaphor, supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund. The $98.2 million[19] rebuilding resulted in five floors instead of three, with a doubling of the display space, as well as new conservation studios and an education centre.[20] The renovated museum re-opened on 7 November 2009.[21][22]

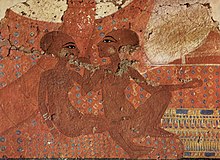

On 26 November 2011, the Ashmolean opened to the public the new galleries of Ancient Egypt and Nubia. This second phase of major redevelopment now allows the museum to exhibit objects that have been in storage for decades, more than doubling the number of coffins and mummies on display. The project received lead support from Lord Sainsbury's Linbury Trust, along with the Selz Foundation, Mr Christian Levett, as well as other trusts, foundations, and individuals. Rick Mather Architects led the redesign and display of the four previous Egypt galleries and the extension to the restored Ruskin Gallery, previously occupied by the museum shop.[23]

In May 2016, the museum opened new galleries dedicated to the display of its collection of Victorian art.[24] This development allowed for the return to the Ashmolean of the Great Bookcase, designed by William Burges, and described as "the most important example of Victorian painted furniture ever made."[24]

Collections

[edit]

The main museum contains huge collections of archaeological specimens and fine art. It has one of the best collections of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, majolica pottery, and English silver. The archaeology department includes the bequest of Arthur Evans and so has a collection of Greek and Minoan pottery. The department also has an extensive collection of antiquities from Ancient Egypt and the Sudan, and the museum hosts the Griffith Institute for the advancement of Egyptology.

Highlights of the Ashmolean's collection include:

- Drawings by Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci

- Paintings by Pablo Picasso, Giambattista Pittoni, Paolo Uccello, Anthony van Dyck, Peter Paul Rubens, Paul Cézanne, John Constable, Titian, Claude Lorrain, Samuel Palmer, John Singer Sargent, Piero di Cosimo, William Holman Hunt, and Edward Burne-Jones

- The Alfred Jewel

- Watercolours and paintings by J. M. W. Turner

- The Messiah Stradivarius, a violin made by Antonio Stradivari[25]

- The Daisy Linda Ward bequest in 1939 of 96 still life paintings, including works by Clara Peeters, Adriaen Coorte, and Rachel Ruysch

- The Pissarro Family Archive, donated in the 1950s to the Ashmolean, consisting of paintings, prints, drawings, books, and letters by Camille Pissarro, Lucien Pissarro, Orovida Camille Pissarro, and other members of the Pissarro family[26]

- Arab ceremonial dress owned by Lawrence of Arabia

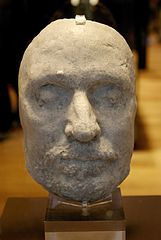

- A death mask of Oliver Cromwell

- The Crondall hoard, a rare set of Anglo-Saxon gold coins discovered in 1828

- A substantial number of Oxyrhynchus Papyri, including Old and New Testament biblical manuscripts

- Over 30 pieces of Late Roman gold glass roundels from the Catacombs of Rome, the 3rd largest collection after the Vatican and British Museum.[27]

- A collection of Posie rings.

- An extensive collection of antiquities from Prehistoric Egypt and the succeeding Early Dynastic Period of Egypt

- The Parian Marble, the earliest extant example of a Greek chronological table

- The Metrological Relief, showing Ancient Greek measurements

- The ceremonial cloak of Chief Powhatan

- The lantern that Gunpowder Plot conspirator Guy Fawkes carried in 1605

- The Minoan collection of Arthur Evans, the biggest outside Crete

- The Narmer Macehead and Scorpion Macehead

- The Kish tablet

- The Sumerian Kings List[28]

- The Abingdon Sword, an Anglo-Saxon sword found at Abingdon south of Oxford

- The Dalboki hoard of Thracian artefacts, central Bulgaria

- The Scythian antiquities from Nymphaeum, Crimea

Recent major bequests and acquisitions include:

- In 2017 the museum acquired a group portrait by William Dobson painted in Oxford around 1645, during the English Civil War. The group in the painting are Prince Rupert, Colonel William Legge (Governor of Oxford) and Colonel John Russell (commander of the prince's elite Blue Coats). The painting was acquired for the nation through the Acceptance in Lieu scheme, administered by Arts Council England.[29][30]

- In 2017 the museum acquired a Viking hoard that was discovered near Watlington in South Oxfordshire in 2015. It is the first large Viking hoard discovered in Oxfordshire, which once lay on the border of Wessex and Mercia. The hoard contains over 200 Anglo-Saxon coins, including many examples of previously rare coins of Alfred the Great, King of Wessex (871–899) and his less well-known contemporary, King Ceolwulf II of Mercia (874–879).[31][32]

- In 2015 the Ashmolean raised the money needed to acquire a major painting by J. M. W. Turner. With lead support from the Heritage Lottery Fund, a grant from the Art Fund, and a public appeal, the fundraising target was met to secure Turner's only full-size townscape in oils: The High Street, Oxford (1810). The painting was accepted by the nation through the Acceptance in Lieu scheme.[33]

- In October 2014 the Ashmolean acquired a painting by John Constable titled Willy Lott's House from the Stour (The Valley Farm). The painting was accepted by the nation through the Acceptance in Lieu scheme. The farm building depicted in the painting is also seen from a different angle in The Hay Wain, painted 1821 and now at the National Gallery.[34][35][36]

- In October 2014 the Ashmolean acquired a collection of historic English embroideries which was given to the museum by collectors Micheál and Elizabeth Feller. The gift comprises 61 pieces which span the whole of the seventeenth century.[37][38]

- In late 2013, art historian and collector Michael Sullivan bequeathed his collection of more than 400 works of art to the museum. The collection, which includes paintings by Chinese masters Qi Baishi, Zhang Daqian, and Wu Guanzhong, was considered one of the world's most significant collections of modern Chinese art. The museum has a gallery dedicated to Sullivan and his wife Khoan.[39]

- In 2013 the museum was given the sculpture Taichi Arch by Taiwanese artist Ju Ming, which was installed on the museum's main forecourt. It was given to the museum by the Juming Culture and Education Foundation in memory of art historian and collector Michael Sullivan.[40]

- In 2012 the museum was left a 500-piece collection of gold and silver objets d'art, including many pieces of Renaissance silverware, assembled by the antique dealer Michael Welby.[41][42]

- In 2012 the museum acquired Édouard Manet's Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus, painted in 1868, after a public campaign to raise £7.83million while a temporary export bar was placed on it by the RCEWA The campaign received £5.9m from the Heritage Lottery Fund, and a grant of £850,000 from The Art Fund.[43]

Collections gallery

[edit]-

The Brighton Pierrots, 1915, by Walter Sickert

-

The Alfred Jewel

-

Music, 1877, by Edward Burne-Jones

-

The "Two Dog Palette" from Hierakonpolis

-

The Messiah Stradivarius violin

-

Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus, by Édouard Manet

-

The Narmer Macehead

-

Studies of the Heads of two Apostles and of their Hands, by Raphael

-

Statue of Sobek, the crocodile god, from the pyramid temple of Amenemhat III

-

Acme and Septimius, c. 1868, by Frederic Leighton, 1st Baron Leighton

-

The Sumerian Kings List, dating to approximately 1800 BC

-

The Apotheosis of Germanicus, a copy after an antique Cameo painted in 1626 by Peter Paul Rubens

-

A death mask of Oliver Cromwell

-

The Return of the Dove to the Ark, 1851, by Sir John Everett Millais

-

A Greek tragic mask dating to the 1st century BC or 1st century AD.

-

Jeanne Holding a Fan, an oil on canvas painting by Camille Pissarro, c. 1874

-

The Holy Family with St John the Baptist, brush and brown wash on panel by Michelangelo

-

Tombstone, the doctor Claudius Agathemerus and his wife Myrtale, from Rome, about AD 100

-

Portrait of John Ruskin by John Everett Millais

-

The Mantle of Chief Powhatan, dating to the 17th century

-

The Abingdon Sword, dating from the late 9th or early 10th century

-

The Annunciation, attributed to Paolo Uccello

-

Restaurant de la Sirène, Asnières, by Vincent van Gogh

-

A Garden in Montmartre by Pierre-Auguste Renoir

-

Young Englishwoman, a costume study by Hans Holbein the Younger

-

A self-portrait by Samuel Palmer

-

A coin of Domitianus II

-

Egyptian Mummy Portrait

-

The Virgin and Child, by Bernardino Pintoricchio

-

Early Bronze Age Cycladic art figurine, 2800–2300 BC.

-

The Kish tablet cast

-

Guy Fawkes' Lantern, London, England c. 1605 Iron and horn

Arundel Marbles

[edit]-

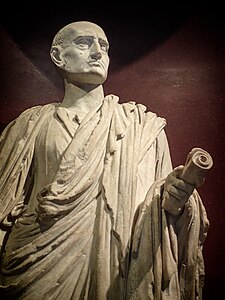

So-called Cicero excavated by the Earl of Arundel in Rome between 1613 and 1614

-

So-called Cicero excavated by the Earl of Arundel in Rome between 1613 and 1614

-

Man wearing a toga excavated in Rome 1613–1614 and later given the name "Caius Marius"

-

First century CE togate torso bearing a 17th century CE head dubbed Caius Marius by the Earl of Arundel excavated in 1613–1614 CE

-

Statue of a woman with hairstyle dating to the later Roman Republican or Augustan period but body dating to 200–100 BCE

-

Closeup of Statue of a woman with hairstyle dating to the later Roman Republican or Augustan period but body dating to 200–100 BCE

-

The Oxford Bust or "Sappho" with head and torso coming from different statues and probably put together by a sculptor in the 1600s

-

The Oxford Bust or "Sappho" with head and torso coming from different statues and probably put together by a sculptor in the 1600s View 2

-

Portrait of a young man with hairstyle, facial features and long neck pointing to portraits made in the early 100s CE

-

Sphinx commissioned by the Earl of Arundel to partner a Roman Sphinx, 17th century CE

-

Sphinx, Roman, 50–200 CE.

-

Roman statue of Eros, 100–200 CE depicting Eros sleeping, his torch turned down, a symbol of death used in many Roman memorials.

-

Closeup of Roman statue of Eros, 100–200 CE depicting Eros sleeping, his torch turned down, a symbol of death used in many Roman memorials.

-

Fragment of a marble sarcophagus depicting two drunken boys from a Bacchic revel, made in Athens 140–150 CE

Broadway Museum and Art Gallery

[edit]In 2013 a museum was opened in the 17th-century "Tudor House" at Broadway, Worcestershire, in the Cotswolds, in partnership with the Ashmolean Museum. In 2017 the museum became known as the Broadway Museum and Art Gallery. The collection includes paintings and furniture from the founding collections of the Ashmolean Museum, given by Elias Ashmole to the University of Oxford in 1683, and local exhibits expand upon elements of the timeline of the village.[44]

Major exhibitions

[edit]Upcoming planned exhibitions include:

- Labyrinth: Knossos, Myth and Reality: This exhibition opened at the Ashmolean in February 2023 and will be open until late July.[45]

Major exhibitions in recent years include:

- Pre-Raphaelites: Drawings & Watercolours: This exhibition, initially shown for 5 weeks in 2021, was re-mounted in 2022 for a longer run, opening in July. It is drawn from the Ashmolean's own collection of Pre-Raphaelite drawings and watercolours.[46]

- Pissarro: Father of Impressionism: Open from February until June 2022, this exhibition included artworks drawn from the Ashmolean's collections as well as international loans, spanning Camille Pissarro's entire career.[47]

- Tokyo: Art and Photography: Open from July 2021 until January 2022, this exhibition included artworks from the Ashmolean's collection as well as loans from Japan and new commissions by contemporary artists. It included woodblock prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige, photography of Moriyama Daido and Ninagawa Mika.[48]

- Pre-Raphaelites: Drawings & Watercolours: Open in May and June 2021, this exhibition was drawn from the Ashmolean's own collection of Pre-Raphaelite drawings and watercolours. The exhibition was curated by British art historian Christiana Payne.[49]

- Young Rembrandt: Open from August until November 2020, this exhibition was delayed due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and featured more than 120 of Rembrandt's paintings, drawings and prints from international and private collections. It focused on the first decade of Rembrandt's work, from 1624 to 1634, and included his early paintings Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem, Self-portrait in a Gorget, Rembrandt Laughing, Judas Repentant, Returning the Pieces of Silver, Portrait of Jacques de Gheyn III, and History Painting. The exhibition was the subject of a BBC television documentary, in its 2020 Museums in Quarantine series.[50][51]

- Last Supper in Pompeii: Open from July 2019 until January 2020, this exhibition explored what the people of the ancient Roman city of Pompeii loved to eat and drink. Many of the objects, on loan from Naples Museum and Pompeii, had never before left Italy.[52]

- Jeff Koons at the Ashmolean: Open from February until June 2019, this exhibition featured 17 major works by the American artist Jeff Koons, 14 of which had never been on display in the UK before. They included some of his most well-known series such as Equilibrium, Banality, Antiquity and his recent Gazing Ball paintings and sculptures. In the galleries of the museum, where the collections range from prehistory to the present, Jeff Koons's work was 'in conversation' with the history of art and ideas which has been his focus over the past four decades. The exhibition was curated by Koons and Norman Rosenthal.[53]

- Spellbound: Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft: Open from August 2018 until January 2019, this exhibition explored the history of magic over eight centuries. On display were 180 objects from 12th-century Europe to newly commissioned contemporary artworks.[54]

- America's Cool Modernism: O'Keeffe to Hopper: Open from March until July 2018 this major exhibition of works by American artists in the early 20th-century included over 80 paintings, photographs and prints, and the first American avant-garde film, Manhatta. Many of the paintings had never before travelled outside the US.[55]

- Imagining the Divine: Art and the Rise of World Religions: Open from October 2017 until February 2018 this exhibition explored Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam and Judaism, and was the first to look at the art of these five world religions as they spread across continents in the first millennium AD.[56]

- Raphael: The Drawings: Open from June 2017 until September 2017 this exhibition brought together over a hundred works by Raphael from international collections and aimed to transform public understanding of Raphael through a focus on the immediacy and expressiveness of his drawing.[57]

- Degas to Picasso: Creating Modernism in France: Open from February 2017 until May 2017, and featuring works by Matisse, Manet, Chagall, Braque, Delacroix, Renoir, Metzinger, Degas, Léger and Picasso, this exhibition told the story of the rise of Modernism through works from a private collection that had never been seen in Britain before.[58][59][60]

- Power and Protection: Islamic Art and the Supernatural: Open from October 2016 until January 2017, this was the first major exhibition to explore the supernatural in the art of the Islamic world. The exhibition included objects and works of art from the 12th to the 20th century, from Morocco to China, which have been used as sources of guidance and protection in the dramatic events of human history. These include dream-books, talismanic charts and amulets.[61][62]

- Storms, War and Shipwrecks: Treasures from the Sicilian Seas: Open from June until September 2016, this exhibition explored the roots of Sicily's multi-cultural heritage through the discoveries made by underwater archaeologists – from chance finds to excavated shipwrecks.[63] The exhibition also featured what has been described as a "flat pack" Byzantine church interior, intended for assembly at its destination, with marble items raised from a wreck off the southeast coast of Sicily in the 1960s by archaeologist Gerhard Kapitan.[64]

- Andy Warhol: Works from the Hall Collection: Open from February until May 2016, this exhibition featured over a hundred works, by Andy Warhol, from the Hall Collection (US), plus loans of films from The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh. Curated by Sir Norman Rosenthal, the exhibition spanned Warhol's entire output, from iconic pieces of the 1960s Pop pioneer to the experimental works of his last decade.[65][66]

- Elizabeth Price: A Restoration: Open from March until May 2016, this two-screen video installation by British artist Elizabeth Price was a newly commissioned work in response to the collections and archives of the Ashmolean and Pitt Rivers museums, in partnership with the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, and funded by the 2013 Contemporary Art Society Award. The main focus was the records of Arthur Evans's excavation of the Cretan city of Knossos.[67][68]

- Drawing in Venice: Titian to Canaletto: Open from October 2015 until January 2016, this exhibition featured a hundred drawings from The Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the Ashmolean, and Christ Church, Oxford. It was based on new research tracing continuities in Venetian drawing over three centuries, from around 1500 down to the foundation of the first academy of art in Venice in 1750.[69] The exhibition also featured 20 works on paper and canvas by contemporary artist Jenny Saville, produced in response to the Venetian drawings in the exhibition.[70]

- Great British Drawings: An exhibition open from March until August 2015 showing more than one hundred British drawings and watercolours from the Ashmolean's collection, spanning three hundred years.[71]

- An Elegant Society: Adam Buck, artist in the age of Jane Austen: Open from July until October 2015 this exhibition explored the work of Adam Buck, Irish Regency era portrait and miniature painter.[71]

- Love Bites: Caricatures by James Gillray: An exhibition in 2015 to mark the 200th anniversary of the death of British caricaturist James Gillray (1757–1815). The caricatures on display were from the collection of New College, Oxford.[71]

- William Blake: Apprentice and Master: Open from December 2014 until March 2015, this exhibition celebrated the work of William Blake.[72]

- Discovering Tutankhamun: a special exhibition, open from July until November 2014, explored Howard Carter's excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922. Original records, drawings and photographs from the Griffith Institute were on display.[73]

- The Eye of the Needle: English Embroideries from the Feller Collection: a special exhibition, open from August until October 2014, of 17th-century embroideries from the Feller Collection, together with examples from the Ashmolean's own holdings.[74]

- Cézanne and the Modern: a special exhibition, open from March to June 2014, displaying Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings and sketches from the Henry and Rose Pearlman Collection[75]

- Francis Bacon / Henry Moore: Flesh and Bone: a special exhibition, open from September 2013 until July 2014, displaying paintings by Francis Bacon and sculptures and drawings by Henry Moore.[76]

- Stradivarius: a special exhibition, open from June until August 2013, exploring the life and work of Antonio Stradivari. It was the first time twenty-one of his instruments, from guitar to cello to violin, were on display together in the UK.[77]

- Master Drawings: a special exhibition, open from May until August 2013, displaying a selection of the Ashmolean's on western art collection. The exhibition surveyed drawings of all types by some of the biggest names in art history, including Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael, as well as Gwen John, David Hockney and Antony Gormley.[78]

- Xu Bing: Landscape Landscript: a special exhibition of the work of Xu Bing, open from February until May 2013. It was the Ashmolean's first major exhibition of contemporary art.[79]

Keepers and Directors

[edit]| Name | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Robert Plot | 1683 | 1690 |

| Edward Lhuyd | 1690 | 1709 |

| David Parry | 1709 | 1714 |

| John Whiteside | 1714 | 1729 |

| George Shepheard | 1730 | 1731 |

| Joseph Andrews | 1731 | 1732 |

| George Huddesford[84] | 1732 | 1755 |

| William Huddesford[84] | 1755 | 1772 |

| William Sheffield | 1772 | 1795 |

| William Lloyd | 1796 | 1815 |

| Thomas Dunbar | 1815 | 1822 |

| John Shute Duncan | 1823 | 1829 |

| Philip Bury Duncan | 1829 | 1854 |

| John Phillips | 1854 | 1870 |

| John Henry Parker | 1870 | 1884 |

| Sir Arthur Evans | 1884 | 1908 |

| David George Hogarth | 1909 | 1927 |

| Edward Thurlow Leeds | 1928 | 1945 |

| Sir Karl Parker | 1945 | 1962 |

| Robert W. Hamilton | 1962 | 1972 |

Beginning in 1973, the position of Keeper was superseded by that of Director:

| Name | From | To |

|---|---|---|

| Sir David Piper | 1973 | 1985 |

| Professor Sir Christopher White | 1985 | 1997 |

| Roger Moorey | 1997 | 1998 |

| Christopher Brown | 1998[85] | 2014[19] |

| Alexander Sturgis | 2014 |

Notable people

[edit]Current keepers

[edit]- Christopher Howgego, Keeper of the Heberden Coin Room

- Mallica Kumbera Landrus, Keeper of Eastern Art

- Paul Roberts, Sackler Keeper of Antiquities

- Catherine Whistler, Keeper of Western Art

Former staff

[edit]- Michael Metcalf, former Keeper of the Heberden Coin Room

- Joan Crowfoot Payne, archaeologist and Cataloguer of the Egyptian and Nubian collectors (1957–1979)

- Jon Whiteley, former Assistant Keeper of Western Art

- Susan Sherratt, former Assistant Curator and Honorary Research Assistant to the Arthur Evans Archive

- Andrew Sherratt, former Assistant Keeper of Antiquities in the Ashmolean Museum

In popular culture

[edit]Books

[edit]- The Ashmolean Museum is a minor location within the book Babel, or the Necessity of Violence.

Comics

[edit]- The 21st book in the Belgian comics series Blake and Mortimer, titled The Oath of the Five Lords, centres around a series of burglaries at the Ashmolean and their connection to T. E. Lawrence.

Television

[edit]- The Alfred Jewel was the inspiration for the Inspector Morse episode "The Wolvercote Tongue" (1988), in which the museum's interior was used as a set.[86]

- The Ashmolean also figures prominently in several episodes of the successor series Lewis, particularly the episode "Point of Vanishing" where the painting The Hunt in the Forest (c. 1470) is a key plot element; the characters visit the painting at the museum and are instructed on its features by an art expert before solving the case.

Theft

[edit]

On 31 December 1999, during the fireworks that accompanied the celebration of the millennium, thieves used scaffolding on an adjoining building to climb onto the roof of the museum and stole Cézanne's landscape painting View of Auvers-sur-Oise. Valued at £3 million, the painting has been described as an important work illustrating the transition from early to mature Cézanne painting.[87] As the thieves ignored other works in the same room, and the stolen Cézanne has not been offered for sale, it is speculated that this was a case of an artwork stolen to order.[88][89] The Cezanne has not been recovered and is one of the FBI's Top Ten Art Crimes.[90]

In 2010 several of the Egypt Exploration Society's Oxyrhynchus Papyri held by the museum were allegedly stolen from the collection and sold to the American Museum of the Bible.[91]

Repatriation of artifacts

[edit]In 2024, the museum agreed to return a 500-year-old bronze sculpture of the Hindu poet and saint Thirumangai Alvar that it had purchased at an auction at Sotheby's in 1967, after the Indian High Commission in the United Kingdom filed a claim stating that the item was stolen from a temple in Tamil Nadu in 1957.[92]

See also

[edit]- Museums of the University of Oxford

- Museum of Oxford

- Oxford University Museum of Natural History

- Bate Collection of Musical Instruments

- Christ Church Picture Gallery

- Donation by Sultan bin Abdul-Aziz Al Saud

References

[edit]- ^ "ALVA – Association of Leading Visitor Attractions". www.alva.org.uk. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins Publishers. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ MacGregor, A. (2001). The Ashmolean Museum. A brief history of the museum and its collections. Ashmolean Museum & Jonathan Horne Publications, London.

- ^ "History of the Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel". kunstmuseumbasel.ch.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Pitt Rivers Museum. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ Salter, H. E.; Lobel, Mary D., eds. (1954). "Victoria County History". A History of the County of Oxford. 3: 47–49.

- ^ Bryson, Bill (2003). A Short History of Nearly Everything (1st ed.). New York: Broadway Books, Random House, Inc. p. 470. ISBN 0-7679-0818-X.

In 1755, some seventy years after the last dodo's death, the director of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford decided that the institution's stuffed dodo was becoming unpleasantly musty and ordered it tossed on a bonfire. This was a surprising decision as it was by this time the only dodo in existence, stuffed or otherwise. A passing employee, aghast, tried to rescue the bird but could save only its head and part of one limb.

- ^ Alden's Oxford Guide. Oxford: Alden & Company. 1946. p. 105.

- ^ Alden's Oxford Guide. Oxford: Alden & Company. 1946. p. 103.

- ^ Evans, Joan. Time and Chance: The story of Arthur Evans and his forebears. London, Longmans, 1943.

- ^ MacGregor, Arthur (2001). The Ashmolean Museum: A Brief History of the Museum and Its Collections. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum Oxford. p. 56.

- ^ "The Ashmolean Museum Oxford Conservation Plan" Archived 2 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine. admin.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved on 24 August 2018.

- ^ Johnston, Stephen. "Astrolabes in Medieval Jewish Society". The Warburg Institute. University of London, School of Advanced Study. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

The Museum of the History of Science in Oxford has the world's largest collection of astrolabes.

- ^ Kraay, C. M. & Sutherland, C. H. V. (1972). The Heberden Coin Room: Origin and Development (PDF) (Revised 1989 and 2001 ed.). Oxford: Ashmolean Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2006.

- ^ "News". Ashmolean.org. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ "Eating and Shopping- Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean.org. 15 April 2012. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ "Chinese Painting Gallery, Ashmolean Museum – van Heyningen and Haward Architects". Vhh.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ Park, Emma (9 November 2009). "Ashes to Ashmolean". Oxonian Review of Books. Archived from the original on 13 March 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

((cite news)): CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Vogel, Carol (20 June 2013). "Director of Ashmolean Museum at Oxford to Step Down". The New York Times.

- ^ The galleries are quirky and unpredictable, full of nooks and crannies and yet completely navigable even to the dyspraxically challenged, like me. That's as much to do with the layout by the exhibition designers Metaphor as with the architecture. Dorment, Richard (2 November 2009). "The reopening of The Ashmolean, review". Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 5 November 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum opens to public". BBC News. 7 November 2009. Archived from the original on 8 November 2009. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- ^ "Transforming: Transformed- Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean.org. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ "Transforming: Egypt – Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean.org. 26 November 2011. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ a b "News & Events".

- ^ "Messiah Violin by Stradivari | Ashmolean Museum". www.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Vickers, Michael, "The Wilshere Collection of Early Christian and Jewish Antiquities in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford," Miscellanea a Emilio Marin Sexagenario Dicata, Kacic, 41–43 (2009–2011), pp. 605–614, PDF Archived 19 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Vickers describes the whole collection, on loan to the museum from Pusey House until bought in 2007. The glass is described at 609–613

- ^ "Sumerian King List | Ashmolean Museum". www.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ "Ashmolean acquires great Civil War portrait by William Dobson". Ashmolean Museum Website. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "New Ashmolean portrait by William Dobson reveals Oxford's civil war role". Oxford Times Website. 16 May 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Funds raised to acquire the Hoard of King Alfred". Ashmolean Museum Website. 1 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Watlington hoard Relics purchased for £1.35m by Ashmolean Museum". BBC News Website. 1 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Ashmolean has raised the money needed to acquire a major painting by JMW Turner". 6 July 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ "John Constable painting transferred to public ownership in lieu of £1m tax". 28 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ "Constable painting donated to the nation". 28 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean acquires painting by John Constable". 28 October 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ "Museum_gets_hooks_into_butcher's_500k_collection". 27 September 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean acquires Feller collection of English Embroidery". 29 September 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean acquires major Chinese art collection". BBC. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean Acquires Monumental Sculpture". 15 November 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ "Metalwork, Jewellery and Watches | Ashmolean Museum". www.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (31 January 2013). "Ashmolean museum in Oxford bequeathed £10m hoard". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ "Manet portrait of Mademoiselle Claus stays in Oxford". BBC News Website. 8 August 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Broadway Museum website". 1 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Ashmolean Membership - Upcoming Exhibitions". www.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Pre-Raphaelites: Drawings & Watercolours Press Release". www.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "Pissarro: Father of Impressionism Exhibition". www.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "New Exhibition Schedule". www.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "Spring Exhibition". www.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "New Dates: Young Rembrandt". www.ashmolean.org. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "Museums in Quarantine, Series 1, Rembrandt". BBC Four. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum 2019 Exhibition Listings". Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum press release for Jeff Koons at the Ashmolean". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum press release for Spellbound". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition America's Cool Modernism". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition Imagining the Divine". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition Raphael The Drawings". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition Degas to Picasso". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition listings 2017". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ "Picasso, Cézanne and Raphael will feature in stunning Ashmolean Museum exhibitions". Oxford Mail news website. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition Power and Protection". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Art Fund What To See – Exhibition Power and Protection". Art Fund website. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition Storms War and Shipwrecks". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "The Storms, War and Shipwrecks' at the Ashmolean Museum in 2016". Archaeology News Network Blog Post. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition Andy Warhol". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Andy Warhol Cultural Icon Celebrity and Provocateur New Ashmolean Exhibition Announced". Artlyst web article: Ashmolean 2016 Andy Warhol exhibition. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition Elizabeth Price A Restoration". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "CAS Annual Award Winner Elizabeth Price's new work to open at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford". Contemporary Art Society website. 24 February 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition Titian to Canaletto". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum exhibition Titian to Canaletto Jenny Saville Drawing". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ a b c "Ashmolean Museum future exhibitions". Ashmolean website future exhibitions. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum". Ashmolean website. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "History 17th century". britisharchaeology.ashmus.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved on 1 September 2018.

- ^ "History 18th century". britisharchaeology.ashmus.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved on 1 September 2018.

- ^ "History 19th century". britisharchaeology.ashmus.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved on 1 September 2018.

- ^ "History 20th century". britisharchaeology.ashmus.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved on 1 September 2018.

- ^ a b M. St John Parker, 'Huddesford, William (bap. 1732, d. 1772)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 16 Feb 2010

- ^ Ashmolean Annual Report 1997-1998 Oxford University Gazette (9 December 1998)

- ^ "Itinerary for Inspector Morse Tour". Oxford, England. TourInADay. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

The Ashmolean Museum is home to The Alfred Jewel that inspired the Inspector Morse episode, The Wolvercote Tongue. This episode ... used the inside of the Ashmolean as a set.

- ^ "FBI – Cezanne". Fbi.gov. 31 December 1999. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (3 February 2000). "Art World Nightmare: Made-to-Order Theft; Stolen Works Like Oxford's Cezanne Can Vanish for Decades". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

... the thief carried with him exactly what he had come for, a $4.8 million Cézanne oil on canvas, 'Auvers-sur-Oise,' which was painted between 1879 and 1882 ...

- ^ Hopkins, Nick (8 January 2000). "How art treasures are stolen to order". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ "Theft of Cezanne's View of Auvers-sur-Oise". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Charlotte Higgins: A scandal in Oxford: the curious case of the stolen gospel - What links an eccentric Oxford classics don, billionaire US evangelicals, and a tiny, missing fragment of an ancient manuscript? Charlotte Higgins unravels a multimillion-dollar riddle, series The long read, The Guardian. In: theguardian.com

- ^ "Oxford University to return bronze sculpture of Hindu saint to India". Associated Press. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Sackler Library

- The Griffith Institute

- Virtual Tour of the Ashmolean Museum, photography from 2003 Archived 3 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Powhatan's Mantle – pictures, description and history

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Academics | |

| Artists | |

| People | |

| Other | |