| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

In mathematics, given two groups, (G,∗) and (H, ·), a group homomorphism from (G,∗) to (H, ·) is a function h : G → H such that for all u and v in G it holds that

where the group operation on the left side of the equation is that of G and on the right side that of H.

From this property, one can deduce that h maps the identity element eG of G to the identity element eH of H,

and it also maps inverses to inverses in the sense that

Hence one can say that h "is compatible with the group structure".

In areas of mathematics where one considers groups endowed with additional structure, a homomorphism sometimes means a map which respects not only the group structure (as above) but also the extra structure. For example, a homomorphism of topological groups is often required to be continuous.

Intuition

[edit]The purpose of defining a group homomorphism is to create functions that preserve the algebraic structure. An equivalent definition of group homomorphism is: The function h : G → H is a group homomorphism if whenever

- a ∗ b = c we have h(a) ⋅ h(b) = h(c).

In other words, the group H in some sense has a similar algebraic structure as G and the homomorphism h preserves that.

Types

[edit]- Monomorphism

- A group homomorphism that is injective (or, one-to-one); i.e., preserves distinctness.

- Epimorphism

- A group homomorphism that is surjective (or, onto); i.e., reaches every point in the codomain.

- Isomorphism

- A group homomorphism that is bijective; i.e., injective and surjective. Its inverse is also a group homomorphism. In this case, the groups G and H are called isomorphic; they differ only in the notation of their elements (except of identity element) and are identical for all practical purposes. I.e. we re-label all elements except identity.

- Endomorphism

- A group homomorphism, h: G → G; the domain and codomain are the same. Also called an endomorphism of G.

- Automorphism

- A group endomorphism that is bijective, and hence an isomorphism. The set of all automorphisms of a group G, with functional composition as operation, itself forms a group, the automorphism group of G. It is denoted by Aut(G). As an example, the automorphism group of (Z, +) contains only two elements, the identity transformation and multiplication with −1; it is isomorphic to (Z/2Z, +).

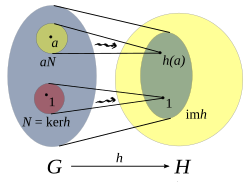

Image and kernel

[edit]We define the kernel of h to be the set of elements in G which are mapped to the identity in H

and the image of h to be

The kernel and image of a homomorphism can be interpreted as measuring how close it is to being an isomorphism. The first isomorphism theorem states that the image of a group homomorphism, h(G) is isomorphic to the quotient group G/ker h.

The kernel of h is a normal subgroup of G:

and the image of h is a subgroup of H.

The homomorphism, h, is a group monomorphism; i.e., h is injective (one-to-one) if and only if ker(h) = {eG}. Injection directly gives that there is a unique element in the kernel, and, conversely, a unique element in the kernel gives injection:

Examples

[edit]- Consider the cyclic group Z3 = (Z/3Z, +) = ({0, 1, 2}, +) and the group of integers (Z, +). The map h : Z → Z/3Z with h(u) = u mod 3 is a group homomorphism. It is surjective and its kernel consists of all integers which are divisible by 3.

- The set

forms a group under matrix multiplication. For any complex number u the function fu : G → C* defined by

- Consider a multiplicative group of positive real numbers (R+, ⋅) for any complex number u. Then the function fu : R+ → C defined by

- The exponential map yields a group homomorphism from the group of real numbers R with addition to the group of non-zero real numbers R* with multiplication. The kernel is {0} and the image consists of the positive real numbers.

- The exponential map also yields a group homomorphism from the group of complex numbers C with addition to the group of non-zero complex numbers C* with multiplication. This map is surjective and has the kernel {2πki : k ∈ Z}, as can be seen from Euler's formula. Fields like R and C that have homomorphisms from their additive group to their multiplicative group are thus called exponential fields.

- The function , defined by is a homomorphism.

- Consider the two groups and , represented respectively by and , where is the positive real numbers. Then, the function defined by the logarithm function is a homomorphism.

Category of groups

[edit]If h : G → H and k : H → K are group homomorphisms, then so is k ∘ h : G → K. This shows that the class of all groups, together with group homomorphisms as morphisms, forms a category.

Homomorphisms of abelian groups

[edit]If G and H are abelian (i.e., commutative) groups, then the set Hom(G, H) of all group homomorphisms from G to H is itself an abelian group: the sum h + k of two homomorphisms is defined by

- (h + k)(u) = h(u) + k(u) for all u in G.

The commutativity of H is needed to prove that h + k is again a group homomorphism.

The addition of homomorphisms is compatible with the composition of homomorphisms in the following sense: if f is in Hom(K, G), h, k are elements of Hom(G, H), and g is in Hom(H, L), then

- (h + k) ∘ f = (h ∘ f) + (k ∘ f) and g ∘ (h + k) = (g ∘ h) + (g ∘ k).

Since the composition is associative, this shows that the set End(G) of all endomorphisms of an abelian group forms a ring, the endomorphism ring of G. For example, the endomorphism ring of the abelian group consisting of the direct sum of m copies of Z/nZ is isomorphic to the ring of m-by-m matrices with entries in Z/nZ. The above compatibility also shows that the category of all abelian groups with group homomorphisms forms a preadditive category; the existence of direct sums and well-behaved kernels makes this category the prototypical example of an abelian category.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Dummit, D. S.; Foote, R. (2004). Abstract Algebra (3rd ed.). Wiley. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-471-43334-7.

- Lang, Serge (2002), Algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 211 (Revised third ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-95385-4, MR 1878556, Zbl 0984.00001

External links

[edit]- Rowland, Todd & Weisstein, Eric W. "Group Homomorphism". MathWorld.

![{\displaystyle \Phi (x)={\sqrt[{}]{2))x}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d48bfca15815808b381b168dddbc7991921afb54)