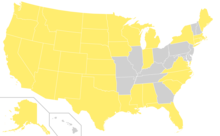

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. As of January 8, 2024[update], 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United States.[1][2] Of these, 228 are located in Alaska and 109 are located in California. 346 of the 574 federally recognized tribes are located in the contiguous United States.[3]

Description

[edit]

Federally recognized tribes are those Native American tribes recognized by the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs as holding a government-to-government relationship with the US federal government.[4] For Alaska Native tribes, see list of Alaska Native tribal entities.

In the United States, the Native American tribe is a fundamental unit of sovereign tribal government. As the Department of the Interior explains, "federally recognized tribes are recognized as possessing certain inherent rights of self-government (i.e., tribal sovereignty)...."[4] The constitution grants to the U.S. Congress the right to interact with tribes. More specifically, the Supreme Court of the United States in United States v. Sandoval, 231 U.S. 28 (1913), warned, "it is not... that Congress may bring a community or body of people within range of this power by arbitrarily calling them an Indian tribe, but only that in respect of distinctly Indian communities the questions whether, to what extent, and for what time they shall be recognized and dealt with as dependent tribes" (at 46).[5] Federal tribal recognition grants to tribes the right to certain benefits, and is largely administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

While trying to determine which groups were eligible for federal recognition in the 1970s, government officials became aware of the need for consistent procedures. To illustrate, several federally unrecognized tribes encountered obstacles in bringing land claims; United States v. Washington (1974) was a court case that affirmed the fishing treaty rights of Washington tribes; and other tribes demanded that the U.S. government recognize aboriginal titles. All the above culminated in the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, which legitimized tribal entities by partially restoring Native American self-determination.[citation needed]

Federal acknowledgment

[edit]Following the decisions made by the Indian Claims Commission in the 1950s, the BIA in 1978 published final rules with procedures that groups had to meet to secure federal tribal acknowledgment. There are seven criteria. Four have proven troublesome for most groups to prove: long-standing historical community, outside identification as Indians, political authority, and descent from a historical tribe. Tribes seeking recognition must submit detailed petitions to the BIA's Office of Federal Acknowledgment.

To be formally recognized as an Indian tribe, the US Congress can legislate recognition or a tribe can meet the seven criteria outlined by the Office of Federal Acknowledgment. These seven criteria are summarized as:

- 83.7(a): "Indian entity identification: The petitioner demonstrates that it has been identified as an American Indian entity on a substantially continuous basis since 1900."[6]

- 83.7(b): "Community: The petitioner demonstrates that it comprises a distinct community and existed as a community from 1900 until the present."[6]

- 83.7(c): "Political influence or authority: The petitioner demonstrates that it has maintained political influence or authority over its members as an autonomous entity from 1900 until the present."[6]

- 83.7(d): "Governing document: The petitioner provides a copy of the group's present governing document including its membership criteria. In the absence of a written document, the petitioner must provide a statement describing in full its membership criteria and current governing procedures."[6]

- 83.7(e): "Descent: The petitioner demonstrates that its membership consists of individuals who descend from a historical Indian tribe or from historical Indian tribes which combined and functioned as a single autonomous political entity."[6]

- 83.7(f): "Unique membership: The petitioner demonstrates that the membership of the petitioning group is composed principally of persons who are not members of any acknowledged North American Indian tribe."[6]

- 83.7(g): "Congressional termination: The Department demonstrates that neither the petitioner nor its members are the subject of congressional legislation that has expressly terminated or forbidden the Federal relationship."[6]

The federal acknowledgment process can take years, even decades; delays of 12 to 14 years have occurred. The Shinnecock Indian Nation formally petitioned for recognition in 1978 and was recognized 32 years later in 2010. At a Senate Committee on Indian Affairs hearing, witnesses testified that the process was "broken, long, expensive, burdensome, intrusive, unfair, arbitrary and capricious, less than transparent, unpredictable, and subject to undue political influence and manipulation."[7][8]

Recent additions

[edit]The number of tribes increased to 567 in May 2016 with the inclusion of the Pamunkey tribe in Virginia who received their federal recognition in July 2015.[2] The number of tribes increased to 573 with the addition of six tribes in Virginia under the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017, signed in January 2018 after the annual list had been published.[1] In July 2018 the United States' Federal Register issued an official list of 573 tribes that are Indian Entities Recognized and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs.[1] The Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana became the 574th tribe to gain federal recognition on December 20, 2019. The website USA.gov, the federal government's official web portal, also maintains an updated list of tribal governments. Ancillary information present in former versions of this list but no longer contained in the current listing has been included here in italic print.

Alphabetical list of federally recognized tribes

[edit]A

[edit]- Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

- Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians of the Agua Caliente Indian Reservation, California

- Ak-Chin Indian Community

(previously listed as Ak Chin Indian Community of the Maricopa (Ak Chin) Indian Reservation, Arizona) - Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas

(previously listed as Alabama-Coushatta Tribes of Texas) - Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town, Oklahoma

- Alturas Indian Rancheria, California

- Apache Tribe of Oklahoma

- Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation, Montana

- Augustine Band of Cahuilla Indians, California

(previously listed as Augustine Band of Cahuilla Mission Indians of the Augustine Reservation)

B

[edit]- Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians of the Bad River Reservation, Wisconsin

- Bay Mills Indian Community, Michigan

- Bear River Band of the Rohnerville Rancheria, California

- Berry Creek Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

- Big Lagoon Rancheria, California

- Big Pine Paiute Tribe of the Owens Valley

(previously listed as Big Pine Band of Owens Valley Paiute Shoshone Indians of the Big Pine Reservation, California) - Big Sandy Rancheria of Western Mono Indians of California

(previously listed as Big Sandy Rancheria of Mono Indians of California) - Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians of the Big Valley Rancheria, California

- Bishop Paiute Tribe

(previously listed as Paiute-Shoshone Indians of the Bishop Community of the Bishop Colony, California) - Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana

- Blue Lake Rancheria, California

- Bridgeport Indian Colony

(previously listed as Bridgeport Paiute Indian Colony of California) - Buena Vista Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians of California

- Burns Paiute Tribe

(previously listed as Burns Paiute Tribe of the Burns Paiute Indian Colony of Oregon)

C

[edit]- Cabazon Band of Cahuilla Indians

(previously listed as Cabazon Band of Mission Indians, California; Cabazon Band of Cahuilla Mission Indians of the Cabazon Reservation) - Cachil DeHe Band of Wintun Indians of the Colusa Indian Community of the Colusa Rancheria, California

- Caddo Nation of Oklahoma

(previously listed as Caddo Indian Tribe of Oklahoma) - Cahto Tribe of the Laytonville Rancheria

(previously listed as Cahto Indian Tribe of the Laytonville Rancheria, California) - Cahuilla Band of Indians

(previously listed as Cahuilla Band of Mission Indians of the Cahuilla Reservation, California) - California Valley Miwok Tribe, California

(previously listed as Sheep Ranch Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians of California) - Campo Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Campo Indian Reservation, California

- Capitan Grande Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of California:

- Catawba Indian Nation

(previously listed as Catawba Tribe of South Carolina) - Cayuga Nation

(previously listed as Cayuga Nation of New York) - Cedarville Rancheria, California

- Chemehuevi Indian Tribe of the Chemehuevi Reservation, California

- Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria, California

- Cherokee Nation

- Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, Oklahoma

(previously listed as Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma) - Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe of the Cheyenne River Reservation, South Dakota

- Chickahominy Indian Tribe

- Chickahominy Indian Tribe–Eastern Division

- Chicken Ranch Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians of California

- Chippewa Cree Indians of the Rocky Boy's Reservation, Montana

(previously listed as Chippewa-Cree Indians of the Rocky Boy's Reservation, Montana) - Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana

- Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Oklahoma

- Cloverdale Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California

- Cocopah Tribe of Arizona

- Coeur D'Alene Tribe

(previously listed as Coeur D'Alene Tribe of the Coeur D'Alene Reservation, Idaho) - Cold Springs Rancheria of Mono Indians of California

- Colorado River Indian Tribes of the Colorado River Indian Reservation, Arizona and California

- Comanche Nation, Oklahoma

(previously listed as Comanche Indian Tribe) - Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation

- Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation

(previously listed as Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Indian Nation of the Yakama Reservation) - Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians of Oregon

(previously listed as Confederated Tribes of the Siletz Reservation) - Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation

- Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation

- Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians

(previously listed as Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians of Oregon) - Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservation, Nevada and Utah

- Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon

- Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation

(previously listed as Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, Oregon) - Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon

- Coquille Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Coquille Tribe of Oregon) - Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana

- Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians

(previously listed as Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians of Oregon) - Cowlitz Indian Tribe

- Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians of California

(previously listed as Coyote Valley Band of Pomo Indians of California) - Crow Creek Sioux Tribe of the Crow Creek Reservation, South Dakota

- Crow Tribe of Montana

D

[edit]- Delaware Nation, Oklahoma

(previously listed as Absentee Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma; Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma) - Delaware Tribe of Indians

(previously listed as Cherokee Delaware; Eastern Delaware) - Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians, California

(previously listed as Dry Creek Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California) - Duckwater Shoshone Tribe of the Duckwater Reservation, Nevada

E

[edit]- Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

(previously listed as Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians of North Carolina) - Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- Eastern Shoshone Tribe of the Wind River Reservation, Wyoming

(previously listed as Shoshone Tribe of the Wind River Reservation, Wyoming) - Elem Indian Colony of Pomo Indians of the Sulphur Bank Rancheria, California

- Elk Valley Rancheria, California

- Ely Shoshone Tribe of Nevada

- Enterprise Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

- Ewiiaapaayp Band of Kumeyaay Indians, California

(previously listed as Cuyapaipe Community of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Cuyapaipe Reservation)

F

[edit]- Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, California

(previously listed as Graton Rancheria; Federated Coast Miwok) - Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe of South Dakota

- Forest County Potawatomi Community, Wisconsin

- Fort Belknap Indian Community of the Fort Belknap Reservation of Montana

- Fort Bidwell Indian Community of the Fort Bidwell Reservation of California

- Fort Independence Indian Community of Paiute Indians of the Fort Independence Reservation, California

- Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes of the Fort McDermitt Indian Reservation, Nevada and Oregon

- Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation, Arizona

(previously listed as Fort McDowell Mohave-Apache Community of the Fort McDowell Indian Reservation) - Fort Mojave Indian Tribe of Arizona, California & Nevada

- Fort Sill Apache Tribe of Oklahoma

G

[edit]- Gila River Indian Community of the Gila River Indian Reservation, Arizona

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Michigan

- Greenville Rancheria

(previously listed as Greenville Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California) - Grindstone Indian Rancheria of Wintun-Wailaki Indians of California

- Guidiville Rancheria of California

H

[edit]- Habematolel Pomo of Upper Lake, California

(previously listed as Upper Lake Band of Pomo Indians of Upper Lake Rancheria of California) - Hannahville Indian Community, Michigan

- Havasupai Tribe of the Havasupai Reservation, Arizona

- Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin

(previously listed as Wisconsin Winnebago Tribe) - Hoh Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Hoh Indian Tribe of the Hoh Indian Reservation, Washington) - Hoopa Valley Tribe, California

- Hopi Tribe of Arizona

- Hopland Band of Pomo Indians, California

(previously listed as Hopland Band of Pomo Indians of the Hopland Rancheria, California) - Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians

(previously listed as Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians of Maine) - Hualapai Indian Tribe of the Hualapai Indian Reservation, Arizona

I

[edit]- Iipay Nation of Santa Ysabel, California

(previously listed as Santa Ysabel Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Santa Ysabel Reservation) - Inaja Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Inaja and Cosmit Reservation, California

- Ione Band of Miwok Indians of California

- Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska

- Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma

J

[edit]- Jackson Band of Miwuk Indians

(previously listed as Jackson Rancheria of Me-Wuk Indians of California) - Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe

(previously listed as Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe of Washington) - Jamul Indian Village of California

- Jena Band of Choctaw Indians

- Jicarilla Apache Nation, New Mexico

(previously listed as Jicarilla Apache Tribe of the Jicarilla Apache Indian Reservation)

K

[edit]- Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians of the Kaibab Indian Reservation, Arizona

- Kalispel Indian Community of the Kalispel Reservation

- Karuk Tribe

(previously listed as Karuk Tribe of California) - Kashia Band of Pomo Indians of the Stewarts Point Rancheria, California

- Kaw Nation, Oklahoma

- Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, Michigan

- Kialegee Tribal Town

- Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas

(previously listed as Texas Band of Traditional Kickapoo) - Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas

- Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma

- Kiowa Indian Tribe of Oklahoma

- Klamath Tribes

- Kletsel Dehe Wintun Nation of the Cortina Rancheria

(previously listed as Kletsel Dehe Band of Wintun Indians) - Koi Nation of Northern California (previously listed as Lower Lake Rancheria, California)

- Kootenai Tribe of Idaho

L

[edit]- La Jolla Band of Luiseno Indians, California

(previously listed as La Jolla Band of Luiseno Mission Indians of the La Jolla Reservation, California) - La Posta Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the La Posta Indian Reservation, California

- Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin

- Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians of the Lac du Flambeau Reservation of Wisconsin

- Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, Michigan

- Las Vegas Tribe of Paiute Indians of the Las Vegas Indian Colony, Nevada

- Little River Band of Ottawa Indians, Michigan[9]

- Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana[10]

- Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, Michigan[9]

- Lone Pine Paiute-Shoshone Tribe

(previously listed as Paiute-Shoshone Indians of the Lone Pine Community of the Lone Pine Reservation, California) - Los Coyotes Band of Cahuilla and Cupeno Indians, California

(previously listed as Los Coyotes Band of Cahuilla & Cupeno Indians of the Los Coyotes Reservation, California; Los Coyotes Band of Cahuilla Mission Indians of the Los Coyotes Reservation) - Lovelock Paiute Tribe of the Lovelock Indian Colony, Nevada

- Lower Brule Sioux Tribe of the Lower Brule Reservation, South Dakota

- Lower Elwha Tribal Community

(previously listed as Lower Elwha Tribal Community of the Lower Elwha Reservation, Washington) - Lower Sioux Indian Community in the State of Minnesota

- Lummi Tribe of the Lummi Reservation

- Lytton Rancheria of California

M

[edit]- Makah Indian Tribe of the Makah Indian Reservation

- Manchester Band of Pomo Indians of the Manchester Rancheria, California

(previously listed as Manchester Band of Pomo Indians of the Manchester-Point Arena Rancheria, California) - Manzanita Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Manzanita Reservation, California

- Mashantucket Pequot Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Mashantucket Pequot Tribe of Connecticut) - Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

(previously listed as Mashpee Wampanoag Indian Tribal Council, Inc., Massachusetts) - Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians of Michigan

(previously listed as Gun Lake Indian Tribe; Gun Lake Village Band & Ottawa Colony Band of Grand River Ottawa Indians) - Mechoopda Indian Tribe of Chico Rancheria, California

- Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin

- Mesa Grande Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Mesa Grande Reservation, California

- Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Reservation, New Mexico

- Miami Tribe of Oklahoma

- Miccosukee Tribe of Indians

- Middletown Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California

- Mi'kmaq Nation

(previously listed as Aroostook Band of Micmacs; Aroostook Band of Micmac Indians) - Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, Minnesota

Six component reservations: - Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians

(previously listed as Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, Mississippi) - Moapa Band of Paiute Indians of the Moapa River Indian Reservation, Nevada

- Modoc Nation

(previously listed as The Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma) - Mohegan Tribe of Indians of Connecticut

(previously listed as Mohegan Indian Tribe of Connecticut) - Monacan Indian Nation

- Mooretown Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

- Morongo Band of Mission Indians, California

(previously listed as Morongo Band of Cahuilla Mission Indians of the Morongo Reservation, California) - Muckleshoot Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Muckleshoot Indian Tribe of the Muckleshoot Reservation, Washington)

N

[edit]- Nansemond Indian Nation

(previously listed as Nansemond Indian Tribe) - Narragansett Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Narragansett Indian Tribe of Rhode Island) - Navajo Nation, Arizona, New Mexico & Utah

- Nez Perce Tribe

(previously listed as Nez Perce Tribe of Idaho) - Nisqually Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Nisqually Indian Tribe of the Nisqually Reservation, Washington) - Nooksack Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Nooksack Indian Tribe of Washington) - Northern Arapaho Tribe of the Wind River Reservation, Wyoming

- Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, Montana

- Northfork Rancheria of Mono Indians of California

- Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation

(previously listed as Northwestern Band of Shoshoni Nation and Northwestern Band of Shoshoni Nation of Utah (Washakie)) - Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, Michigan

(previously listed as Huron Potawatomi, Inc.)

O

[edit]- Oglala Sioux Tribe, South Dakota

(previously listed as Oglala Sioux Tribe of the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota) - Ohkay Owingeh, New Mexico

(previously listed as Pueblo of San Juan) - Omaha Tribe of Nebraska

- Oneida Indian Nation

(previously listed as Oneida Nation of New York)[11] - Oneida Nation

(previously listed as Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin)[11] - Onondaga Nation, New York

(previously listed as Onondaga Nation of New York) - Otoe-Missouria Tribe of Indians, Oklahoma

- Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma

P

[edit]- Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah

- Paiute-Shoshone Tribe of the Fallon Reservation and Colony, Nevada

- Pala Band of Mission Indians

(previously listed as Pala Band of Luiseno Mission Indians of the Pala Reservation, California) - Pamunkey Indian Tribe[12]

- Pascua Yaqui Tribe of Arizona

- Paskenta Band of Nomlaki Indians of California

- Passamaquoddy Tribe

(previously listed as Passamaquoddy Tribe of Maine) - Pauma Band of Luiseno Mission Indians of the Pauma & Yuima Reservation, California

- Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma

- Pechanga Band of Indians

(previously listed as Pechanga Band of Luiseno Mission Indians of the Pechanga Reservation, California) - Penobscot Nation

(previously listed as Penobscot Tribe of Maine) - Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

- Picayune Rancheria of Chukchansi Indians of California

- Pinoleville Pomo Nation, California

(previously listed as Pinoleville Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California) - Pit River Tribe, California

includes: - Poarch Band of Creek Indians

(previously listed as Poarch Band of Creeks, Poarch Band of Creek Indians of Alabama, Creek Nation East of the Mississippi) - Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, Michigan and Indiana

- Ponca Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

- Ponca Tribe of Nebraska

- Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe

(previously listed as Port Gamble Band of S'Klallam Indians; Port Gamble Indian Community of the Port Gamble Reservation, Washington) - Potter Valley Tribe, California

(previously listed as Potter Valley Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California) - Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation

(previously listed as Prairie Band of Potawatomi Nation, Kansas; Prairie Band of Potawatomi Indians) - Prairie Island Indian Community in the State of Minnesota

- Pueblo of Acoma, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Cochiti, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Isleta, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Jemez, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Laguna, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Nambe, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Picuris, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Pojoaque, New Mexico

- Pueblo of San Felipe, New Mexico

- Pueblo of San Ildefonso, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Sandia, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Santa Ana, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Santa Clara, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Taos, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Tesuque, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Zia, New Mexico

- Pulikla Tribe of Yurok People[13]

(previously listed as Resighini Rancheria, California; Coast Indian Community of Yurok Indians of the Resighini Rancheria) - Puyallup Tribe of Indians

- Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe of the Pyramid Lake Reservation, Nevada

Q

[edit]- Quapaw Nation

(previously listed as Quapaw Tribe of Indians; Quapaw Tribe of Indians, Oklahoma) - Quartz Valley Indian Community of the Quartz Valley Reservation of California

- Quechan Tribe of the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation, California & Arizona

- Quileute Tribe of the Quileute Reservation

(previously listed as Quileute Tribe of the Quileute Reservation, Washington) - Quinault Indian Nation

(previously listed as Quinault Tribe of the Quinault Reservation, Washington)

R

[edit]- Ramona Band of Cahuilla, California

(previously listed as Ramona Band or Village of Cahuilla Mission Indians of California) - Rappahannock Tribe, Inc.

- Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin

- Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, Minnesota

- Redding Rancheria, California

- Redwood Valley or Little River Band of Pomo Indians of the Redwood Valley Rancheria California

(previously listed as Redwood Valley Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California) - Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, Nevada

- Rincon Band of Luiseno Mission Indians of Rincon Reservation, California

(previously listed as Rincon Band of Luiseno Indians) - Robinson Rancheria

(previously listed as Robinson Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians, California, and Robinson Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California) - Rosebud Sioux Tribe of the Rosebud Indian Reservation, South Dakota

- Round Valley Indian Tribes, Round Valley Reservation, California

(previously listed as Round Valley Indian Tribes of the Round Valley Reservation, California; Covelo Indian Community)

S

[edit]- Sac & Fox Nation of Missouri in Kansas and Nebraska

- Sac & Fox Nation, Oklahoma

- Sac & Fox Tribe of the Mississippi in Iowa

- Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan

- Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe

(previously listed as St. Regis Band of Mohawk Indians of New York) - Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community of the Salt River Reservation, Arizona

- Samish Indian Nation

(previously listed as Samish Indian Tribe, Washington) - San Carlos Apache Tribe of the San Carlos Reservation, Arizona

- San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe of Arizona

- San Pasqual Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of California

- Santa Rosa Band of Cahuilla Indians, California

(previously listed as Santa Rosa Band of Cahuilla Mission Indians of the Santa Rosa Reservation) - Santa Rosa Indian Community of the Santa Rosa Rancheria, California

- Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Mission Indians of the Santa Ynez Reservation, California

- Santee Sioux Nation, Nebraska

(previously listed as Santee Sioux Tribe of the Santee Reservation of Nebraska) - Santo Domingo Pueblo

(previously listed as Kewa Pueblo, New Mexico and Pueblo of Santo Domingo) - Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe of Washington) - Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, Michigan

(previously listed as Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Michigan) - Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians of California

- Seminole Tribe of Florida

(previously also listing its reservations:) - Seneca Nation of Indians

(previously listed as Seneca Nation of New York) - Seneca-Cayuga Nation

(previously listed as Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of Oklahoma) - Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community of Minnesota

- Shawnee Tribe

(previously listed as Shawnee Tribe, Oklahoma) - Sherwood Valley Rancheria of Pomo Indians of California

- Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians, Shingle Springs Rancheria (Verona Tract), California

- Shinnecock Indian Nation

(previously listed as Shinnecock Indian Nation, New York) - Shoalwater Bay Indian Tribe of the Shoalwater Bay Indian Reservation

(previously listed as Shoalwater Bay Tribe of the Shoalwater Bay Indian Reservation, Washington) - Shoshone-Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Reservation

(previously listed as Shoshone-Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Reservation of Idaho) - Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Reservation, Nevada

- Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate of the Lake Traverse Reservation, South Dakota

- Skokomish Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Skokomish Indian Tribe of the Skokomish Reservation, Washington) - Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians of Utah

- Snoqualmie Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Snoqualmie Tribe, Washington) - Soboba Band of Luiseno Indians, California

(previously listed as Soboba Band of Luiseno Mission Indians of the Soboba Reservation) - Sokaogon Chippewa Community, Wisconsin

- Southern Ute Indian Tribe of the Southern Ute Reservation, Colorado

- Spirit Lake Tribe, North Dakota

- Spokane Tribe of the Spokane Reservation

- Squaxin Island Tribe of the Squaxin Island Reservation

(previously listed as Squaxin Island Tribe of the Squaxin Island Reservation, Washington) - St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin

- Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North & South Dakota

- Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians of Washington

(previously listed as Stillaguamish Tribe of Washington) - Stockbridge Munsee Community, Wisconsin

- Summit Lake Paiute Tribe of Nevada

- Suquamish Indian Tribe of the Port Madison Reservation

(previously listed as Suquamish Indian Tribe of the Port Madison Reservation, Washington) - Susanville Indian Rancheria, California

- Swinomish Indian Tribal Community

(previously listed as Swinomish Indians of the Swinomish Reservation of Washington; Swinomish Indians of the Swinomish Reservation, Washington) - Sycuan Band of the Kumeyaay Nation

(previously listed as Sycuan Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of California)

T

[edit]- Table Mountain Rancheria

(previously listed as Table Mountain Rancheria of California) - Tejon Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Tejon Indian Tribe of California) - Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone Indians of Nevada

Four constituent bands: - The Chickasaw Nation

- The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma

- The Muscogee (Creek) Nation

(previously listed as Muscogee (Creek) Nation, Oklahoma) - The Osage Nation

(previously listed as Osage Tribe, Oklahoma) - The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma

(previously listed as Seminole Nation of Oklahoma) - Thlopthlocco Tribal Town, Oklahoma

- Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation, North Dakota

- Timbisha Shoshone Tribe

(previously listed as Death Valley Timbi-sha Shoshone Tribe of California; Death Valley Timbi-Sha Shoshone Band of California).[a] - Tohono O'odham Nation of Arizona

- Tolowa Dee-ni' Nation

(previously listed as Smith River Rancheria, California) - Tonawanda Band of Seneca

(previously listed as Tonawanda Band of Seneca Indians of New York) - Tonkawa Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma

- Tonto Apache Tribe of Arizona

- Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians, California

(previously listed as Torres-Martinez Band of Cahuilla Mission Indians of California) - Tulalip Tribes of Washington

(previously listed as Tulalip Tribes of the Tulalip Reservation, Washington) - Tule River Indian Tribe of the Tule River Reservation, California

- Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe of Louisiana) - Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians of the Tuolumne Rancheria of California

- Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians of North Dakota

- Tuscarora Nation

(previously listed as Tuscarora Nation of New York) - Twenty-Nine Palms Band of Mission Indians of California

U

[edit]- United Auburn Indian Community of the Auburn Rancheria of California

- United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma

- Upper Mattaponi Tribe

- Upper Sioux Community, Minnesota

- Upper Skagit Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Upper Skagit Indian Tribe of Washington) - Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah & Ouray Reservation, Utah

- Ute Mountain Ute Tribe

(previously listed as Ute Mountain Tribe of the Ute Mountain Reservation, Colorado, New Mexico & Utah) - Utu Utu Gwaitu Paiute Tribe of the Benton Paiute Reservation, California

V

[edit]W

[edit]- Walker River Paiute Tribe of the Walker River Reservation, Nevada

- Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)

(previously listed as Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) of Massachusetts; Wampanoag Tribal Council of Gay Head, Inc.) - Washoe Tribe of Nevada & California

- White Mountain Apache Tribe of the Fort Apache Reservation, Arizona

- Wichita and Affiliated Tribes (Wichita, Keechi, Waco & Tawakonie), Oklahoma

- Wilton Rancheria, California

- Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska

- Winnemucca Indian Colony of Nevada

- Wiyot Tribe, California

(previously listed as Table Bluff Reservation—Wiyot Tribe) - Wyandotte Nation

(previously listed as Wyandotte Nation, Oklahoma)

X

[edit]Y

[edit]- Yankton Sioux Tribe of South Dakota

- Yavapai-Apache Nation of the Camp Verde Indian Reservation, Arizona

- Yavapai-Prescott Indian Tribe

(previously listed as Yavapai-Prescott Tribe of the Yavapai Reservation, Arizona) - Yerington Paiute Tribe of the Yerington Colony & Campbell Ranch, Nevada

- Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation, California

(previously listed as Rumsey Indian Rancheria of Wintun Indians of California) - Yomba Shoshone Tribe of the Yomba Reservation, Nevada

- Ysleta del Sur Pueblo

(previously listed as Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo of Texas) - Yuhaaviatam of San Manuel Nation

(previously listed as San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, California; San Manuel Band of Serrano Mission Indians of the San Manuel Reservation, California) - Yurok Tribe of the Yurok Reservation, California

Z

[edit]See also

[edit]- United States

- List of Alaska Native tribal entities

- List of historical Indian reservations in the United States

- List of Indian reservations in the United States

- List of organizations that self-identify as Native American tribes

- Native American Heritage Sites (U.S. National Park Service)

- Native Americans in the United States

- Outline of United States federal Indian law and policy

- State-recognized tribes in the United States

- Tribal sovereignty

- (Federally or state) unrecognized tribes

- Federal recognition of Native Hawaiians

- Canada

Federal Register

[edit]The Federal Register is used by the BIA to publish the list of "Indian Entities Recognized and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Tribes in the contiguous 48 states and those in Alaska are listed separately.

Current version

[edit]Former versions

[edit]- Federal Register, Volume 87, FR 4636, dated January 12, 2023 (87 FR 4636) – 574 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 85, Number 20 dated January 30, 2020 (85 FR 5462) – 574 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 84, Number 22 dated February 1, 2019 (84 FR 1200) – 573 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 83, Number 141 dated July 23, 2018 (83 FR 34863) – 573 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 83, Number 20 dated January 30, 2018 (83 FR 4235) – 567 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 82, Number 10 dated January 17, 2017 (82 FR 4915) – 567 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 81, Number 86 dated May 4, 2016 (81 FR 26826) – 567 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 81, Number 19 dated January 29, 2016 (81 FR 5019) – 566 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 80, Number 9 dated January 14, 2015 (80 FR 1942) – 566 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 78, Number 87 dated May 6, 2013 (78 FR 26384) – 566 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 77, Number 155 dated August 10, 2012 (77 FR 47868) – 566 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 75, Number 190 dated October 1, 2010 (75 FR 60810), with a supplemental listing published in Federal Register, Volume 75, Number 207 dated October 27, 2010 (75 FR 66124) – 565+1 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 74, Number 153 dated August 11, 2009 (74 FR 40218) – 564 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 73, Number 66 dated April 4, 2008 (73 FR 18553) – 562 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 72, Number 55 dated March 22, 2007 (72 FR 13648) – 561 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 70, Number 226 dated November 25, 2005 (70 FR 71194) – 561 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 68, Number 234 dated December 5, 2003 (68 FR 68180) – 562 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 67, Number 134 dated July 12, 2002 (67 FR 46328) – 562 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 65, Number 49 dated March 13, 2000 (65 FR 13298) – 556 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 63, Number 250 dated December 30, 1998 (63 FR 71941) – 555 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 62, Number 205 dated October 23, 1997 (62 FR 55270) – 555 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 61, Number 220 dated November 13, 1996 (61 FR 58211) – 555 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 60, Number 32 dated February 16, 1995 (60 FR 9250) – 552 entities

- Federal Register, Volume 58, Number 202 dated October 21, 1993 (58 FR 54364)

- Federal Register, Volume 53, Number 250 dated December 29, 1988 (53 FR 52829)

- Federal Register, Volume 47, Number 227 dated November 24, 1982 (47 FR 53133) – First time listing that includes native entities within the state of Alaska

- Federal Register, Volume 44, Number 26 dated February 6, 1979 (44 FR 7235) – First listing of Indian tribal entities within the contiguous 48 states

Notes

[edit]- ^ The hyphen in Timbisha is actually ungrammatical and based on a clerical error. The tribe itself always uses Timbisha, without the hyphen. "Timbisha" is a compound of tüm 'rock' + pisa 'red paint', so the hyphen in the middle of pisa is impossible

References

[edit] This article incorporates public domain material from 85 FR 5462 - Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs. United States Government.

This article incorporates public domain material from 85 FR 5462 - Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs. United States Government.

- ^ a b c Bureau of Indian Affairs, Interior. (January 8, 2024). "Notice Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Federal Register. 89 (944): 944–48. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ a b Federal Acknowledgment of the Pamunkey Indian Tribe Archived 2015-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Alaska Region | Indian Affairs". www.bia.gov. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ^ a b "Why Tribes Exist Today in the United States". Frequently Asked Questions. Bureau of Indian Affairs, US Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

- ^ Sheffield (1998) p. 56

- ^ a b c d e f g "25 CFR Part 83 – Procedures for Federal Acknowledgment of Indian Tribes" (PDF). Office of Federal Acknowledgment. Office of Indian Affairs, US Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 22, 2022.

- ^ Toensing, Gale Courey (September 13, 2018). "Federal Recognition Process: A Culture of Neglect". Indian Country Today. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- ^ Fixing the Federal Acknowledgment Process (S. Hrg. 111-470), Hearing Before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate (Nov. 4, 2009). Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ a b "s 1357 in session 103 - A Bill To Reaffirm And Clarify The Federal Relationships Of The Little Traverse Bay Bands Of Odawa Indians And The Little River Band Of Ottawa Indians As Distinct Federally Recognized Indian Tribes, And For Other Purposes". Thepoliticalguide.com.

- ^ McLaughlin, Kathleen (December 21, 2019). "A big moment finally comes for the Little Shell: Federal recognition of their tribe". Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Federal Registrar, July 23, 2018: p. 34865

- ^ Heim, Joe (July 2, 2015). "A renowned Virginia Indian tribe finally wins federal recognition". Washington Post. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ "Resighini Rancheria Becomes Pulikla Tribe of Yurok People, Honoring Ancestral Lands and Cultural Heritage". Native News Online. July 11, 2024. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Miller, Mark Edwin. Forgotten Tribes: Unrecognized Indians and the Federal Acknowledgment Process. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004; Bison Books, 2006.