| Migraine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Woman with migraine headache | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Headaches, nausea, sensitivity to light, sound, and smell[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Around puberty[1] |

| Duration | Recurrent, long term[1] |

| Causes | Environmental and genetic[3] |

| Risk factors | Family history, female[4][5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Subarachnoid hemorrhage, venous thrombosis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, brain tumor, tension headache, sinusitis,[6] cluster headache[7][unreliable medical source?] |

| Prevention | Propranolol, amitriptyline, topiramate[8] |

| Medication | Ibuprofen, paracetamol (acetaminophen), triptans, ergotamines[5][9] |

| Prevalence | ~15%[10] |

Migraine (UK: /ˈmiːɡreɪn/, US: /ˈmaɪ-/)[11][12] is a genetically influenced complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea and light and sound sensitivity.[1] Other characterizing symptoms may include vomiting, cognitive dysfunction, allodynia, and dizziness. Exacerbation of headache symptoms during physical activity is another distinguishing feature.[13] Up to one-third of migraine sufferers experience aura, a premonitory period of sensory disturbance widely accepted to be caused by cortical spreading depression at the onset of a migraine attack.[13] Although primarily considered to be a headache disorder, migraine is highly heterogenous in its clinical presentation and is better thought of as a spectrum disease rather than a distinct clinical entity.[14] Disease burden can range from episodic discrete attacks to chronic disease.[14][15]

Migraine is believed to be caused by a mixture of environmental and genetic factors that influence the excitation and inhibition of nerve cells in the brain.[3] An older "vascular hypothesis" postulated that the aura of migraine is produced by vasoconstriction and the headache of migraine is produced by vasodilation, but the vasoconstrictive mechanism has been disproven,[16] and the role of vasodilation in migraine pathophysiology is uncertain.[17][18] The accepted hypothesis suggests that multiple primary neuronal impairments lead to a series of intracranial and extracranial changes, triggering a physiological cascade that leads to migraine symptomatology.[19]

Initial recommended treatment for acute attacks is with over-the-counter analgesics (pain medication) such as ibuprofen and paracetamol (acetaminophen) for headache, antiemetics (anti-nausea medication) for nausea, and the avoidance of triggers.[9] Specific medications such as triptans, ergotamines, or CGRP inhibitors may be used in those experiencing headaches that are refractory to simple pain medications.[20] For individuals who experience four or more attacks per month, or could otherwise benefit from prevention, prophylactic medication is recommended.[21] Commonly prescribed prophylactic medications include beta blockers like propranolol, anticonvulsants like sodium valproate, antidepressants like amitriptyline, and other off-label classes of medications.[8] Preventive medications inhibit migraine pathophysiology through various mechanisms, such as blocking calcium and sodium channels, blocking gap junctions, and inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases, among other mechanisms.[22][23] Nonpharmacological preventative therapies include nutritional supplementation, dietary interventions, sleep improvement, and aerobic exercise.[24]

Globally, approximately 15% of people are affected by migraine.[10] In the Global Burden of Disease Study, conducted in 2010, migraines ranked as the third-most prevalent disorder in the world.[25] It most often starts at puberty and is worst during middle age.[1] As of 2016[update], it is one of the most common causes of disability.[26]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Migraine typically presents with self-limited, recurrent severe headache associated with autonomic symptoms.[5][27] About 15–30% of people living with migraine experience episodes with aura,[9][28] and they also frequently experience episodes without aura.[29] The severity of the pain, duration of the headache, and frequency of attacks are variable.[5] A migraine attack lasting longer than 72 hours is termed status migrainosus.[30] There are four possible phases to a migraine attack, although not all the phases are necessarily experienced:[13]

- The prodrome, which occurs hours or days before the headache

- The aura, which immediately precedes the headache

- The pain phase, also known as headache phase

- The postdrome, the effects experienced following the end of a migraine attack

Migraine is associated with major depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and obsessive–compulsive disorder. These psychiatric disorders are approximately 2–5 times more common in people without aura, and 3–10 times more common in people with aura.[31]

Prodrome phase

[edit]Prodromal or premonitory symptoms occur in about 60% of those with migraines,[2][32] with an onset that can range from two hours to two days before the start of pain or the aura.[33] These symptoms may include a wide variety of phenomena,[34] including altered mood, irritability, depression or euphoria, fatigue, craving for certain food(s), stiff muscles (especially in the neck), constipation or diarrhea, and sensitivity to smells or noise.[32] This may occur in those with either migraine with aura or migraine without aura.[35] Neuroimaging indicates the limbic system and hypothalamus as the origin of prodromal symptoms in migraine.[36]

Aura phase

[edit] |

|

|

|

Aura is a transient focal neurological phenomenon that occurs before or during the headache.[2] Aura appears gradually over a number of minutes (usually occurring over 5–60 minutes) and generally lasts less than 60 minutes.[37][38] Symptoms can be visual, sensory or motoric in nature, and many people experience more than one.[39] Visual effects occur most frequently: they occur in up to 99% of cases and in more than 50% of cases are not accompanied by sensory or motor effects.[39] If any symptom remains after 60 minutes, the state is known as persistent aura.[40]

Visual disturbances often consist of a scintillating scotoma (an area of partial alteration in the field of vision which flickers and may interfere with a person's ability to read or drive).[2] These typically start near the center of vision and then spread out to the sides with zigzagging lines which have been described as looking like fortifications or walls of a castle.[39] Usually the lines are in black and white but some people also see colored lines.[39] Some people lose part of their field of vision known as hemianopsia while others experience blurring.[39]

Sensory aura are the second most common type; they occur in 30–40% of people with auras.[39] Often a feeling of pins-and-needles begins on one side in the hand and arm and spreads to the nose–mouth area on the same side.[39] Numbness usually occurs after the tingling has passed with a loss of position sense.[39] Other symptoms of the aura phase can include speech or language disturbances, world spinning, and less commonly motor problems.[39] Motor symptoms indicate that this is a hemiplegic migraine, and weakness often lasts longer than one hour unlike other auras.[39] Auditory hallucinations or delusions have also been described.[41]

Pain phase

[edit]Classically the headache is unilateral, throbbing, and moderate to severe in intensity.[37] It usually comes on gradually[37] and is aggravated by physical activity during a migraine attack.[13] However, the effects of physical activity on migraine are complex, and some researchers have concluded that, while exercise can trigger migraine attacks, regular exercise may have a prophylactic effect and decrease frequency of attacks.[42] The feeling of pulsating pain is not in phase with the pulse.[43] In more than 40% of cases, however, the pain may be bilateral (both sides of the head), and neck pain is commonly associated with it.[44] Bilateral pain is particularly common in those who have migraine without aura.[2] Less commonly pain may occur primarily in the back or top of the head.[2] The pain usually lasts 4 to 72 hours in adults;[37] however, in young children frequently lasts less than 1 hour.[45] The frequency of attacks is variable, from a few in a lifetime to several a week, with the average being about one a month.[46][47]

The pain is frequently accompanied by nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light, sensitivity to sound, sensitivity to smells, fatigue, and irritability.[2] Many thus seek a dark and quiet room.[48] In a basilar migraine, a migraine with neurological symptoms related to the brain stem or with neurological symptoms on both sides of the body,[49] common effects include a sense of the world spinning, light-headedness, and confusion.[2] Nausea occurs in almost 90% of people, and vomiting occurs in about one-third.[48] Other symptoms may include blurred vision, nasal stuffiness, diarrhea, frequent urination, pallor, or sweating.[50] Swelling or tenderness of the scalp may occur as can neck stiffness.[50] Associated symptoms are less common in the elderly.[51]

Silent migraine

[edit]Sometimes, aura occurs without a subsequent headache.[39] This is known in modern classification as a typical aura without headache, or acephalgic migraine in previous classification, or commonly as a silent migraine.[52][53] However, silent migraine can still produce debilitating symptoms, with visual disturbance, vision loss in half of both eyes, alterations in color perception, and other sensory problems, like sensitivity to light, sound, and odors.[54] It can last from 15 to 30 minutes, usually no longer than 60 minutes, and it can recur or appear as an isolated event.[53]

Postdrome

[edit]The migraine postdrome could be defined as that constellation of symptoms occurring once the acute headache has settled.[55] Many report a sore feeling in the area where the migraine was, and some report impaired thinking for a few days after the headache has passed. The person may feel tired or "hung over" and have head pain, cognitive difficulties, gastrointestinal symptoms, mood changes, and weakness.[56] According to one summary, "Some people feel unusually refreshed or euphoric after an attack, whereas others note depression and malaise."[57][unreliable medical source?]

Cause

[edit]The underlying causes of migraines are unknown.[58] However, they are believed to be related to a mix of environmental and genetic factors.[3] They run in families in about two-thirds of cases[5] and rarely occur due to a single gene defect.[59] While migraines were once believed to be more common in those of high intelligence, this does not appear to be true.[46] A number of psychological conditions are associated, including depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.[60]

Success of the surgical migraine treatment by decompression of extracranial sensory nerves adjacent to vessels[61] suggests that migraineurs may have anatomical predisposition for neurovascular compression that may be caused by both intracranial and extracranial vasodilation due to migraine triggers. This, along with the existence of numerous cranial neural interconnections,[62] may explain the multiple cranial nerve involvement and consequent diversity of migraine symptoms.[63]

Genetics

[edit]Studies of twins indicate a 34% to 51% genetic influence of likelihood to develop migraine.[3] This genetic relationship is stronger for migraine with aura than for migraines without aura.[29] It is clear from family and populations studies, that migraine is a complex disorders, where numerous of genetic risk variants exist, and where each variant increase the risk of migraine marginally.[64][65] It is also known that having several of these risk variants increase the risk by a small to moderate amount.[59]

Single gene disorders that result in migraines are rare.[59] One of these is known as familial hemiplegic migraine, a type of migraine with aura, which is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.[66][67] Four genes have been shown to be involved in familial hemiplegic migraine.[68] Three of these genes are involved in ion transport.[68] The fourth is the axonal protein PRRT2, associated with the exocytosis complex.[68] Another genetic disorder associated with migraine is CADASIL syndrome or cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy.[2] One meta-analysis found a protective effect from angiotensin converting enzyme polymorphisms on migraine.[69] The TRPM8 gene, which codes for a cation channel, has been linked to migraines.[70]

The common forms migraine are Polygenetic, where common variants of numerous genes contributes to the predisposition for migraine. These genes can be placed in three categories increaseing the risk of migraine in general, specifically migraine with aura, or migraine without aura.[71][72] Three of these genes, CALCA, CALCB, and HTR1F are already target for migraine specific treatments. Five genes are specific risk to migraine with aura, PALMD, ABO, LRRK2, CACNA1A and PRRT2, and 13 genes are specific to migriane without aura. Using the accumulated genetic risk of the common variations, into a so-called polygenetic risk, it is possible to assess e.g. the treatment response to triptans.[73][74]

Triggers

[edit]Migraine may be induced by triggers, with some reporting it as an influence in a minority of cases[5] and others the majority.[75] Many things such as fatigue, certain foods, alcohol, and weather have been labeled as triggers; however, the strength and significance of these relationships are uncertain.[75][76] Most people with migraines report experiencing triggers.[77] Symptoms may start up to 24 hours after a trigger.[5]

Physiological aspects

[edit]Common triggers quoted are stress, hunger, and fatigue (these equally contribute to tension headaches).[75] Psychological stress has been reported as a factor by 50 to 80% of people.[78] Migraine has also been associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and abuse.[79] Migraine episodes are more likely to occur around menstruation.[78] Other hormonal influences, such as menarche, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, perimenopause, and menopause, also play a role.[80] These hormonal influences seem to play a greater role in migraine without aura.[46] Migraine episodes typically do not occur during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, or following menopause.[2]

Dietary aspects

[edit]Between 12% and 60% of people report foods as triggers.[81][82]

There are many reports[83][84][85][86][87] that tyramine – which is naturally present in chocolate, alcoholic beverages, most cheeses, processed meats, and other foods – can trigger migraine symptoms in some individuals. Monosodium glutamate (MSG) has been reported as a trigger for migraine,[88] but a systematic review concluded that "a causal relationship between MSG and headache has not been proven... It would seem premature to conclude that the MSG present in food causes headache".[89]

Environmental aspects

[edit]A 2009 review on potential triggers in the indoor and outdoor environment concluded that while there were insufficient studies to confirm environmental factors as causing migraine, "migraineurs worldwide consistently report similar environmental triggers".[90]

Pathophysiology

[edit]

Migraine is believed to be primarily a neurological disorder,[91][92] while others believe it to be a neurovascular disorder with blood vessels playing the key role, although evidence does not support this completely.[93][94][95][96] Others believe both are likely important.[97][98][99][100] One theory is related to increased excitability of the cerebral cortex and abnormal control of pain neurons in the trigeminal nucleus of the brainstem.[101]

Sensitization of trigeminal pathways is a key pathophysiological phenomenon in migraine. It is debatable whether sensitization starts in the periphery or in the brain.[102][103]

Aura

[edit]Cortical spreading depression, or spreading depression according to Leão, is a burst of neuronal activity followed by a period of inactivity, which is seen in those with migraines with aura.[104] There are a number of explanations for its occurrence, including activation of NMDA receptors leading to calcium entering the cell.[104] After the burst of activity, the blood flow to the cerebral cortex in the area affected is decreased for two to six hours.[104] It is believed that when depolarization travels down the underside of the brain, nerves that sense pain in the head and neck are triggered.[104]

Pain

[edit]The exact mechanism of the head pain which occurs during a migraine episode is unknown.[105] Some evidence supports a primary role for central nervous system structures (such as the brainstem and diencephalon),[106] while other data support the role of peripheral activation (such as via the sensory nerves that surround blood vessels of the head and neck).[105] The potential candidate vessels include dural arteries, pial arteries and extracranial arteries such as those of the scalp.[105] The role of vasodilatation of the extracranial arteries, in particular, is believed to be significant.[107]

Neuromodulators

[edit]Adenosine, a neuromodulator, may be involved.[108] Released after the progressive cleavage of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine acts on adenosine receptors to put the body and brain in a low activity state by dilating blood vessels and slowing the heart rate, such as before and during the early stages of sleep. Adenosine levels have been found to be high during migraine attacks.[108][109] Caffeine's role as an inhibitor of adenosine may explain its effect in reducing migraine.[110] Low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin, also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), are also believed to be involved.[111]

Calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRPs) have been found to play a role in the pathogenesis of the pain associated with migraine, as levels of it become elevated during an attack.[9][43]

Diagnosis

[edit]The diagnosis of a migraine is based on signs and symptoms.[5] Neuroimaging tests are not necessary to diagnose migraine, but may be used to find other causes of headaches in those whose examination and history do not confirm a migraine diagnosis.[112] It is believed that a substantial number of people with the condition remain undiagnosed.[5]

The diagnosis of migraine without aura, according to the International Headache Society, can be made according the "5, 4, 3, 2, 1 criteria," which is as follows:[13]

- Five or more attacks – for migraine with aura, two attacks are sufficient for diagnosis.

- Four hours to three days in duration

- Two or more of the following:

- Unilateral (affecting one side of the head)

- Pulsating

- Moderate or severe pain intensity

- Worsened by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity

- One or more of the following:

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Sensitivity to both light (photophobia) and sound (phonophobia)

If someone experiences two of the following: photophobia, nausea, or inability to work or study for a day, the diagnosis is more likely.[113] In those with four out of five of the following: pulsating headache, duration of 4–72 hours, pain on one side of the head, nausea, or symptoms that interfere with the person's life, the probability that this is a migraine attack is 92%.[9] In those with fewer than three of these symptoms, the probability is 17%.[9]

Classification

[edit]Migraine was first comprehensively classified in 1988.[29]

The International Headache Society updated their classification of headaches in 2004.[13] A third version was published in 2018.[114] According to this classification, migraine is a primary headache disorder along with tension-type headaches and cluster headaches, among others.[115]

Migraine is divided into six subclasses (some of which include further subdivisions):[116]

- Migraine without aura, or "common migraine", involves migraine headaches that are not accompanied by aura.

- Migraine with aura, or "classic migraine", usually involves migraine headaches accompanied by aura. Less commonly, aura can occur without a headache, or with a nonmigraine headache. Two other varieties are familial hemiplegic migraine and sporadic hemiplegic migraine, in which a person has migraine with aura and with accompanying motor weakness. If a close relative has had the same condition, it is called "familial", otherwise it is called "sporadic". Another variety is basilar-type migraine, where a headache and aura are accompanied by difficulty speaking, world spinning, ringing in ears, or a number of other brainstem-related symptoms, but not motor weakness. This type was initially believed to be due to spasms of the basilar artery, the artery that supplies the brainstem. Now that this mechanism is not believed to be primary, the symptomatic term migraine with brainstem aura (MBA) is preferred.[49] Retinal migraine (which is distinct from visual or optical migraine) involves migraine headaches accompanied by visual disturbances or even temporary blindness in one eye.

- Childhood periodic syndromes that are commonly precursors of migraine include cyclical vomiting (occasional intense periods of vomiting), abdominal migraine (abdominal pain, usually accompanied by nausea), and benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood (occasional attacks of vertigo).

- Complications of migraine describe migraine headaches and/or auras that are unusually long or unusually frequent, or associated with a seizure or brain lesion.

- Probable migraine describes conditions that have some characteristics of migraines, but where there is not enough evidence to diagnose it as a migraine with certainty (in the presence of concurrent medication overuse).

- Chronic migraine is a complication of migraines, and is a headache that fulfills diagnostic criteria for migraine headache and occurs for a greater time interval. Specifically, greater or equal to 15 days/month for longer than 3 months.[117]

Abdominal migraine

[edit]The diagnosis of abdominal migraine is controversial.[118] Some evidence indicates that recurrent episodes of abdominal pain in the absence of a headache may be a type of migraine[118][119] or are at least a precursor to migraines.[29] These episodes of pain may or may not follow a migraine-like prodrome and typically last minutes to hours.[118] They often occur in those with either a personal or family history of typical migraine.[118] Other syndromes that are believed to be precursors include cyclical vomiting syndrome and benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood.[29]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Other conditions that can cause similar symptoms to a migraine headache include temporal arteritis, cluster headaches, acute glaucoma, meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage.[9] Temporal arteritis typically occurs in people over 50 years old and presents with tenderness over the temple, cluster headache presents with one-sided nose stuffiness, tears and severe pain around the orbits, acute glaucoma is associated with vision problems, meningitis with fevers, and subarachnoid hemorrhage with a very fast onset.[9] Tension headaches typically occur on both sides, are not pounding, and are less disabling.[9]

Those with stable headaches that meet criteria for migraines should not receive neuroimaging to look for other intracranial disease.[120][121][122] This requires that other concerning findings such as papilledema (swelling of the optic disc) are not present. People with migraines are not at an increased risk of having another cause for severe headaches.[citation needed]

Management

[edit]Management of migraine includes prevention of migraine attacks and rescue treatment. There are three main aspects of treatment: trigger avoidance, acute (abortive), and preventive (prophylactic) control.[123]

Prognosis

[edit]"Migraine exists on a continuum of different attack frequencies and associated levels of disability."[124] For those with occasional, episodic migraine, a "proper combination of drugs for prevention and treatment of migraine attacks" can limit the disease's impact on patients' personal and professional lives.[125] But fewer than half of people with migraine seek medical care and more than half go undiagnosed and undertreated.[126] "Responsive prevention and treatment of migraine is incredibly important" because evidence shows "an increased sensitivity after each successive attack, eventually leading to chronic daily migraine in some individuals."[125] Repeated migraine results in "reorganization of brain circuitry," causing "profound functional as well as structural changes in the brain."[127] "One of the most important problems in clinical migraine is the progression from an intermittent, self-limited inconvenience to a life-changing disorder of chronic pain, sensory amplification, and autonomic and affective disruption. This progression, sometimes termed chronification in the migraine literature, is common, affecting 3% of migraineurs in a given year, such that 8% of migraineurs have chronic migraine in any given year." Brain imagery reveals that the electrophysiological changes seen during an attack become permanent in people with chronic migraine; "thus, from an electrophysiological point of view, chronic migraine indeed resembles a never-ending migraine attack."[127] Severe migraine ranks in the highest category of disability, according to the World Health Organization, which uses objective metrics to determine disability burden for the authoritative annual Global Burden of Disease report. The report classifies severe migraine alongside severe depression, active psychosis, quadriplegia, and terminal-stage cancer.[128]

Migraine with aura appears to be a risk factor for ischemic stroke[129] doubling the risk.[130] Being a young adult, being female, using hormonal birth control, and smoking further increases this risk.[129] There also appears to be an association with cervical artery dissection.[131] Migraine without aura does not appear to be a factor.[132] The relationship with heart problems is inconclusive with a single study supporting an association.[129] Migraine does not appear to increase the risk of death from stroke or heart disease.[133] Preventative therapy of migraines in those with migraine with aura may prevent associated strokes.[134] People with migraine, particularly women, may develop higher than average numbers of white matter brain lesions of unclear significance.[135]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Migraine is common, with around 33% of women and 18% of men affected at some point in their lifetime.[136] Onset can be at any age, but prevalence rises sharply around puberty, and remains high until declining after age 50.[136] Before puberty, boys and girls are equally impacted, with around 5% of children experiencing migraines. From puberty onwards, women experience migraines at greater rates than men. From age 30 to 50, up to 4 times as many women experience migraines as men.[136], this is most pronouched in migraine without aura.[137]

Worldwide, migraine affects nearly 15% or approximately one billion people.[10] In the United States, about 6% of men and 18% of women experience a migraine attack in a given year, with a lifetime risk of about 18% and 43% respectively.[5] In Europe, migraines affect 12–28% of people at some point in their lives with about 6–15% of adult men and 14–35% of adult women getting at least one yearly.[138] Rates of migraine are slightly lower in Asia and Africa than in Western countries.[46][139] Chronic migraine occurs in approximately 1.4 to 2.2% of the population.[140]

During perimenopause symptoms often get worse before decreasing in severity.[141] While symptoms resolve in about two-thirds of the elderly, in 3–10% they persist.[51]

History

[edit]

An early description consistent with migraine is contained in the Ebers Papyrus, written around 1500 BCE in ancient Egypt.[142]

The word migraine is from the Greek ἡμικρᾱνίᾱ (hēmikrāníā), 'pain in half of the head',[143] from ἡμι- (hēmi-), 'half' and κρᾱνίον (krāníon), 'skull'.[144]

In 200 BCE, writings from the Hippocratic school of medicine described the visual aura that can precede the headache and a partial relief occurring through vomiting.[145]

A second-century description by Aretaeus of Cappadocia divided headaches into three types: cephalalgia, cephalea, and heterocrania.[146] Galen of Pergamon used the term hemicrania (half-head), from which the word migraine was eventually derived.[146] He also proposed that the pain arose from the meninges and blood vessels of the head.[145] Migraine was first divided into the two now used types – migraine with aura (migraine ophthalmique) and migraine without aura (migraine vulgaire) in 1887 by Louis Hyacinthe Thomas, a French Librarian.[145] The mystical visions of Hildegard von Bingen, which she described as "reflections of the living light", are consistent with the visual aura experienced during migraines.[147]

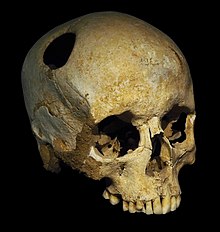

Trepanation, the deliberate drilling of holes into a skull, was practiced as early as 7,000 BCE.[142] While sometimes people survived, many would have died from the procedure due to infection.[148] It was believed to work via "letting evil spirits escape".[149] William Harvey recommended trepanation as a treatment for migraines in the 17th century.[150] The association between trepanation and headaches in ancient history may simply be a myth or unfounded speculation that originated several centuries later. In 1913, the world-famous American physician William Osler misinterpreted the French anthropologist and physician Paul Broca's words about a set of children's skulls from the Neolithic age that he found during the 1870s. These skulls presented no evident signs of fractures that could justify this complex surgery for mere medical reasons. Trepanation was probably born of superstitions, to remove "confined demons" inside the head, or to create healing or fortune talismans with the bone fragments removed from the skulls of the patients. However, Osler wanted to make Broca's theory more palatable to his modern audiences, and explained that trepanation procedures were used for mild conditions such as "infantile convulsions headache and various cerebral diseases believed to be caused by confined demons."[151]

While many treatments for migraine have been attempted, it was not until 1868 that use of a substance which eventually turned out to be effective began.[145] This substance was the fungus ergot from which ergotamine was isolated in 1918 [152] and first used to treat migraines in 1925.[153] Methysergide was developed in 1959 and the first triptan, sumatriptan, was developed in 1988.[152] During the 20th century with better study-design, effective preventive measures were found and confirmed.[145]

Society and culture

[edit]Migraine is a significant source of both medical costs and lost productivity. It has been estimated that migraine is the most costly neurological disorder in the European Community, costing more than €27 billion per year.[154] In the United States, direct costs have been estimated at $17 billion, while indirect costs – such as missed or decreased ability to work – is estimated at $15 billion.[155] Nearly a tenth of the direct cost is due to the cost of triptans.[155] In those who do attend work during a migraine attack, effectiveness is decreased by around a third.[154] Negative impacts also frequently occur for a person's family.[154]

Research

[edit]Prevention mechanisms

[edit]Transcranial magnetic stimulation shows promise,[9][156] as does transcutaneous supraorbital nerve stimulation.[157] There is preliminary evidence that a ketogenic diet may help prevent episodic and long-term migraine.[158][159]

Sex dependency

[edit]Statistical data indicates that women may be more prone to having migraine, showing migraine incidence three times higher among women than men.[160][161] The Society for Women's Health Research has also mentioned hormonal influences, mainly estrogen, as having a considerable role in provoking migraine pain. Studies and research related to the sex dependencies of migraine are still ongoing, and conclusions have yet to be achieved.[162][163][164]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Headache disorders Fact sheet N°277". October 2012. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Simon RP, Aminoff MJ, Greenberg DA (2009). Clinical neurology (7 ed.). New York, N.Y: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill. pp. 85–88. ISBN 9780071664332.

- ^ a b c d Piane M, Lulli P, Farinelli I, Simeoni S, De Filippis S, Patacchioli FR, et al. (December 2007). "Genetics of migraine and pharmacogenomics: some considerations". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 8 (6): 334–339. doi:10.1007/s10194-007-0427-2. PMC 2779399. PMID 18058067.

- ^ Lay CL, Broner SW (May 2009). "Migraine in women". Neurologic Clinics. 27 (2): 503–11. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2009.01.002. PMID 19289228.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bartleson JD, Cutrer FM (May 2010). "Migraine update. Diagnosis and treatment". Minnesota Medicine. 93 (5): 36–41. PMID 20572569.

- ^ Swanson JW, Sakai F (2006). "Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Migraines". In Olesen J (ed.). The Headaches. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-7817-5400-2. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Cluster Headache". American Migraine Foundation. 15 February 2017. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ a b Kumar A, Kadian R (September 2022). "Migraine Prophylaxis". StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29939650. Bookshelf ID: NBK507873. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gilmore B, Michael M (February 2011). "Treatment of acute migraine headache". American Family Physician. 83 (3): 271–280. PMID 21302868.

- ^ a b c Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- ^ Wells JC (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Jones D (2011). Roach P, Setter J, Esling J (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (2004). "The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition". Cephalalgia. 24 (Suppl 1): 9–160. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00653.x. PMID 14979299.

- ^ a b Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, Lipton RB (February 2012). "Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 16 (1): 86–92. doi:10.1007/s11916-011-0233-z. PMC 3258393. PMID 22083262.

- ^ Shankar Kikkeri N, Nagalli S (December 2022). "Migraine With Aura". StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32119498. Bookshelf ID: NBK554611. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Amin FM, Asghar MS, Hougaard A, Hansen AE, Larsen VA, de Koning PJ, et al. (May 2013). "Magnetic resonance angiography of intracranial and extracranial arteries in patients with spontaneous migraine without aura: a cross-sectional study". The Lancet. Neurology. 12 (5): 454–461. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70067-X. PMID 23578775. S2CID 25553357. Archived from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ Mason BN, Russo AF (2018). "Vascular Contributions to Migraine: Time to Revisit?". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 12: 233. doi:10.3389/fncel.2018.00233. PMC 6088188. PMID 30127722.

- ^ Jacobs B, Dussor G (December 2016). "Neurovascular contributions to migraine: Moving beyond vasodilation". Neuroscience. 338: 130–144. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.012. PMC 5083225. PMID 27312704.

- ^ Burstein R, Noseda R, Borsook D (April 2015). "Migraine: multiple processes, complex pathophysiology". The Journal of Neuroscience. 35 (17): 6619–6629. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0373-15.2015. PMC 4412887. PMID 25926442.

- ^ Tzankova V, Becker WJ, Chan TL (January 2023). "Diagnosis and acute management of migraine". CMAJ. 195 (4): E153–E158. doi:10.1503/cmaj.211969. PMC 9888545. PMID 36717129. Archived from the original on 4 July 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ Silberstein SD (August 2015). "Preventive Migraine Treatment". Continuum. 21 (4 Headache): 973–989. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000199. PMC 4640499. PMID 26252585. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ Noseda R, Burstein R (December 2013). "Migraine pathophysiology: anatomy of the trigeminovascular pathway and associated neurological symptoms, CSD, sensitization and modulation of pain". Pain. 154 (Suppl 1): S44–S53. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.021. PMC 3858400. PMID 24347803.

- ^ Spierings EL (July 2001). "Mechanism of migraine and action of antimigraine medications". The Medical Clinics of North America. 85 (4): 943–958, vi–vii. doi:10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70352-7. PMID 11480266. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ Haghdoost F, Togha M (1 January 2022). "Migraine management: Non-pharmacological points for patients and health care professionals". Open Medicine. 17 (1): 1869–1882. doi:10.1515/med-2022-0598. PMC 9691984. PMID 36475060.

- ^ Gobel H. "1. Migraine". ICHD-3 The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, et al. (GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (September 2017). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". Lancet. 390 (10100): 1211–1259. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2. PMC 5605509. PMID 28919117.

- ^ Bigal ME, Lipton RB (June 2008). "The prognosis of migraine". Current Opinion in Neurology. 21 (3): 301–8. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e328300c6f5. PMID 18451714. S2CID 34805084.

- ^ Gutman SA (2008). Quick reference neuroscience for rehabilitation professionals: the essential neurologic principles underlying rehabilitation practice (2nd ed.). Thorofare, NJ: SLACK. p. 231. ISBN 9781556428005. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Olesen J, Goadsby PJ (2006). "The Migraines: Introduction". In Olesen J (ed.). The Headaches (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-0-7817-5400-2. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ Tfelt-Hansen P, Young WB, Silberstein (2006). "Antiemetic, Prokinetic, Neuroleptic and Miscellaneous Drugs in the Acute Treatment of Migraine". In Olesen J (ed.). The Headaches (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 512. ISBN 978-0-7817-5400-2. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016.

- ^ Baskin SM, Lipchik GL, Smitherman TA (October 2006). "Mood and anxiety disorders in chronic headache". Headache. 46 (Suppl 3): S76-87. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00559.x. PMID 17034402. S2CID 35451906.

- ^ a b Lynn DJ, Newton HB, Rae-Grant A (2004). The 5-minute neurology consult. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 26. ISBN 9780683307238. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ Buzzi MG, Cologno D, Formisano R, Rossi P (October–December 2005). "Prodromes and the early phase of the migraine attack: therapeutic relevance". Functional Neurology. 20 (4): 179–83. PMID 16483458.

- ^ Rossi P, Ambrosini A, Buzzi MG (October–December 2005). "Prodromes and predictors of migraine attack". Functional Neurology. 20 (4): 185–91. PMID 16483459.

- ^ Ropper AH, Adams RD, Victor M, Samuels MA (2009). Adams and Victor's principles of neurology (9 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. Chapter 10. ISBN 9780071499927.

- ^ May A, Burstein R (November 2019). "Hypothalamic regulation of headache and migraine". Cephalalgia. 39 (13): 1710–1719. doi:10.1177/0333102419867280. PMC 7164212. PMID 31466456.

- ^ a b c d Tintinalli JE (2010). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. 1116–1117. ISBN 978-0-07-148480-0.

- ^ Ashina M (November 2020). "Migraine". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (19): 1866–1876. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1915327. PMID 33211930. S2CID 227078662.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Cutrer FM, Olesen J (2006). "Migraines with Aura and Their Subforms". In Olesen J (ed.). The Headaches (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 238–240. ISBN 978-0-7817-5400-2. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ Viana M, Sances G, Linde M, Nappi G, Khaliq F, Goadsby PJ, et al. (August 2018). "Prolonged migraine aura: new insights from a prospective diary-aided study". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 19 (1): 77. doi:10.1186/s10194-018-0910-y. PMC 6119171. PMID 30171359.

- ^ Slap, GB (2008). Adolescent medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 105. ISBN 9780323040730. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ Amin FM, Aristeidou S, Baraldi C, Czapinska-Ciepiela EK, Ariadni DD, Di Lenola D, et al. (September 2018). "The association between migraine and physical exercise". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 19 (1): 83. doi:10.1186/s10194-018-0902-y. PMC 6134860. PMID 30203180.

- ^ a b Qubty W, Patniyot I (June 2020). "Migraine Pathophysiology". Pediatric Neurology. 107: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.12.014. PMID 32192818. S2CID 213191464.

- ^ Tepper SJ, Tepper DE (1 January 2011). The Cleveland Clinic manual of headache therapy. New York: Springer. p. 6. ISBN 9781461401780. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016.

- ^ Bigal ME, Arruda MA (July 2010). "Migraine in the pediatric population--evolving concepts". Headache. 50 (7): 1130–43. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01717.x. PMID 20572878. S2CID 23256755.

- ^ a b c d Rasmussen BK (2006). "Epidemiology of Migraine". In Olesen J (ed.). The Headaches (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 238–240. ISBN 978-0-7817-5400-2. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ Dalessio DJ (2001). Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Dalessio DJ (eds.). Wolff's headache and other head pain (7 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 122. ISBN 9780195135183.

- ^ a b Lisak RP, Truong DD, Carroll W, Bhidayasiri R (2009). International neurology: a clinical approach. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 670. ISBN 9781405157384.

- ^ a b Kaniecki RG (June 2009). "Basilar-type migraine". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 13 (3): 217–20. doi:10.1007/s11916-009-0036-7. PMID 19457282. S2CID 22242504.

- ^ a b Glaser JS (1999). Neuro-ophthalmology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 555. ISBN 9780781717298. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ a b Dodick DW, Capobianco DJ (2008). "Chapter 14: Headaches". In Sirven JI, Malamut BL (eds.). Clinical neurology of the older adult (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 197. ISBN 9780781769471. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017.

- ^ Robblee J (21 August 2019). "Silent Migraine: A Guide". American Migraine Foundation. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ a b He Y, Li Y, Nie Z (February 2015). "Typical aura without headache: a case report and review of the literature". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 9 (1): 40. doi:10.1186/s13256-014-0510-7. PMC 4344793. PMID 25884682.

- ^ Leonard J (7 September 2018). Han S (ed.). "Silent migraine: Symptoms, causes, treatment, prevention". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Bose P, Goadsby PJ (June 2016). "The migraine postdrome". Current Opinion in Neurology. 29 (3): 299–301. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000310. PMID 26886356. S2CID 22445093.

- ^ Kelman L (February 2006). "The postdrome of the acute migraine attack". Cephalalgia. 26 (2): 214–20. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01026.x. PMID 16426278. S2CID 21519111.

- ^ Halpern AL, Silberstein SD (2005). "Ch. 9: The Migraine Attack—A Clinical Description". In Kaplan PW, Fisher RS (eds.). Imitators of Epilepsy (2 ed.). New York: Demos Medical. ISBN 978-1-888799-83-5. NBK7326. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ Robbins MS, Lipton RB (April 2010). "The epidemiology of primary headache disorders". Seminars in Neurology. 30 (2): 107–19. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1249220. PMID 20352581. S2CID 260317083.

- ^ a b c Schürks M (January 2012). "Genetics of migraine in the age of genome-wide association studies". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 13 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s10194-011-0399-0. PMC 3253157. PMID 22072275.

- ^ The Headaches, pp. 246–247

- ^ Bink T, Duraku LS, Ter Louw RP, Zuidam JM, Mathijssen IM, Driessen C (December 2019). "The Cutting Edge of Headache Surgery: A Systematic Review on the Value of Extracranial Surgery in the Treatment of Chronic Headache". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 144 (6): 1431–1448. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006270. PMID 31764666. S2CID 208273535.

- ^ Adair D, Truong D, Esmaeilpour Z, Gebodh N, Borges H, Ho L, et al. (May 2020). "Electrical stimulation of cranial nerves in cognition and disease". Brain Stimulation. 13 (3): 717–750. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2020.02.019. PMC 7196013. PMID 32289703.

- ^ Villar-Martinez MD, Goadsby PJ (September 2022). "Pathophysiology and Therapy of Associated Features of Migraine". Cells. 11 (17): 2767. doi:10.3390/cells11172767. PMC 9455236. PMID 36078174.

- ^ Gormley P, Kurki MI, Hiekkala ME, Veerapen K, Häppölä P, Mitchell AA, et al. (May 2018). "Common Variant Burden Contributes to the Familial Aggregation of Migraine in 1,589 Families". Neuron. 98 (4): 743–753.e4. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.04.014. PMC 5967411. PMID 29731251.

- ^ Harder AV, Terwindt GM, Nyholt DR, van den Maagdenberg AM (February 2023). "Migraine genetics: Status and road forward". Cephalalgia. 43 (2): 3331024221145962. doi:10.1177/03331024221145962. PMID 36759319.

- ^ de Vries B, Frants RR, Ferrari MD, van den Maagdenberg AM (July 2009). "Molecular genetics of migraine". Human Genetics. 126 (1): 115–32. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0684-z. PMID 19455354. S2CID 20119237.

- ^ Montagna P (September 2008). "Migraine genetics". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 8 (9): 1321–30. doi:10.1586/14737175.8.9.1321. PMID 18759544. S2CID 207195127.

- ^ a b c Ducros A (May 2013). "[Genetics of migraine]". Revue Neurologique. 169 (5): 360–71. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2012.11.010. PMID 23618705.

- ^ Wan D, Wang C, Zhang X, Tang W, Chen M, Dong Z, et al. (1 January 2016). "Association between angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism and migraine: a meta-analysis". The International Journal of Neuroscience. 126 (5): 393–9. doi:10.3109/00207454.2015.1025395. PMID 26000817. S2CID 34902092.

- ^ Dussor G, Cao YQ (October 2016). "TRPM8 and Migraine". Headache. 56 (9): 1406–1417. doi:10.1111/head.12948. PMC 5335856. PMID 27634619.

- ^ Bjornsdottir G, Chalmer MA, Stefansdottir L, Skuladottir AT, Einarsson G, Andresdottir M, et al. (November 2023). "Rare variants with large effects provide functional insights into the pathology of migraine subtypes, with and without aura". Nature Genetics. 55 (11): 1843–1853. doi:10.1038/s41588-023-01538-0. PMC 10632135. PMID 37884687.

- ^ Hautakangas H, Winsvold BS, Ruotsalainen SE, Bjornsdottir G, Harder AV, Kogelman LJ, et al. (February 2022). "Genome-wide analysis of 102,084 migraine cases identifies 123 risk loci and subtype-specific risk alleles". Nature Genetics. 54 (2): 152–160. doi:10.1038/s41588-021-00990-0. PMID 35115687.

- ^ Mikol DD, Picard H, Klatt J, Wang A, Peng C, Stefansson K (14 April 2020). "Migraine Polygenic Risk Score Is Associated with Severity of Migraine – Analysis of Genotypic Data from Four Placebo-controlled Trials of Erenumab (1214)". Neurology. 94 (15_supplement). doi:10.1212/WNL.94.15_supplement.1214. ISSN 0028-3878.

- ^ Kogelman LJ, Esserlind AL, Francke Christensen A, Awasthi S, Ripke S, Ingason A, et al. (December 2019). "Migraine polygenic risk score associates with efficacy of migraine-specific drugs". Neurology. Genetics. 5 (6): e364. doi:10.1212/NXG.0000000000000364. PMC 6878840. PMID 31872049.

- ^ a b c Levy D, Strassman AM, Burstein R (June 2009). "A critical view on the role of migraine triggers in the genesis of migraine pain". Headache. 49 (6): 953–7. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01444.x. PMID 19545256. S2CID 31707887.

- ^ Martin PR (June 2010). "Behavioral management of migraine headache triggers: learning to cope with triggers". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 14 (3): 221–7. doi:10.1007/s11916-010-0112-z. PMID 20425190. S2CID 5511782.

- ^ Pavlovic JM, Buse DC, Sollars CM, Haut S, Lipton RB (2014). "Trigger factors and premonitory features of migraine attacks: summary of studies". Headache. 54 (10): 1670–9. doi:10.1111/head.12468. PMID 25399858. S2CID 25016889.

- ^ a b Radat F (May 2013). "[Stress and migraine]". Revue Neurologique. 169 (5): 406–12. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2012.11.008. PMID 23608071.

- ^ Peterlin BL, Katsnelson MJ, Calhoun AH (October 2009). "The associations between migraine, unipolar psychiatric comorbidities, and stress-related disorders and the role of estrogen". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 13 (5): 404–12. doi:10.1007/s11916-009-0066-1. PMC 3972495. PMID 19728969.

- ^ Chai NC, Peterlin BL, Calhoun AH (June 2014). "Migraine and estrogen". Current Opinion in Neurology. 27 (3): 315–24. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000091. PMC 4102139. PMID 24792340.

- ^ Finocchi C, Sivori G (May 2012). "Food as trigger and aggravating factor of migraine". Neurological Sciences. 33 (Suppl 1): S77-80. doi:10.1007/s10072-012-1046-5. PMID 22644176. S2CID 19582697.

- ^ Rockett FC, de Oliveira VR, Castro K, Chaves ML, Perla A, Perry ID (June 2012). "Dietary aspects of migraine trigger factors". Nutrition Reviews. 70 (6): 337–56. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00468.x. PMID 22646127.

- ^ Ghose K, Carroll JD (1984). "Mechanism of tyramine-induced migraine: similarity with dopamine and interactions with disulfiram and propranolol in migraine patients". Neuropsychobiology. 12 (2–3): 122–126. doi:10.1159/000118123. PMID 6527752.

- ^ Moffett A, Swash M, Scott DF (August 1972). "Effect of tyramine in migraine: a double-blind study". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 35 (4): 496–499. doi:10.1136/jnnp.35.4.496. PMC 494110. PMID 4559027.

- ^ "Tyramine and Migraines: What You Need to Know". excedrin.com. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition (Second ed.). Academic Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-12-227055-0.

- ^ Özturan A, Şanlıer N, Coşkun Ö (2016). "The Relationship Between Migraine and Nutrition" (PDF). Turk J Neurol. 22 (2): 44–50. doi:10.4274/tnd.37132. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Sun-Edelstein C, Mauskop A (June 2009). "Foods and supplements in the management of migraine headaches" (PDF). The Clinical Journal of Pain. 25 (5): 446–452. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.530.1223. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31819a6f65. PMID 19454881. S2CID 3042635. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2017.

- ^ Obayashi Y, Nagamura Y (17 May 2016). "Does monosodium glutamate really cause headache? : a systematic review of human studies". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 17 (1): 54. doi:10.1186/s10194-016-0639-4. PMC 4870486. PMID 27189588.

- ^ Friedman DI, De ver Dye T (June 2009). "Migraine and the environment". Headache. 49 (6): 941–52. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01443.x. PMID 19545255. S2CID 29764274.

- ^ Andreou AP, Edvinsson L (December 2019). "Mechanisms of migraine as a chronic evolutive condition". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 20 (1): 117. doi:10.1186/s10194-019-1066-0. PMC 6929435. PMID 31870279.

- ^ "Migraine". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 11 July 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Hoffmann J, Baca SM, Akerman S (April 2019). "Neurovascular mechanisms of migraine and cluster headache". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 39 (4): 573–594. doi:10.1177/0271678x17733655. PMC 6446418. PMID 28948863.

- ^ Brennan KC, Charles A (June 2010). "An update on the blood vessel in migraine". Current Opinion in Neurology. 23 (3): 266–74. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833821c1. PMC 5500293. PMID 20216215.

- ^ Spiri D, Titomanlio L, Pogliani L, Zuccotti G (January 2012). "Pathophysiology of migraine: The neurovascular theory". Headaches: Causes, Treatment and Prevention: 51–64.

- ^ Goadsby PJ (January 2009). "The vascular theory of migraine--a great story wrecked by the facts". Brain. 132 (Pt 1): 6–7. doi:10.1093/brain/awn321. PMID 19098031.

- ^ Dodick DW (April 2008). "Examining the essence of migraine--is it the blood vessel or the brain? A debate". Headache. 48 (4): 661–7. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01079.x. PMID 18377395. S2CID 6272233.

- ^ Chen D, Willis-Parker M, Lundberg GP (October 2020). "Migraine headache: Is it only a neurological disorder? Links between migraine and cardiovascular disorders". Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 30 (7): 424–430. doi:10.1016/j.tcm.2019.10.005. PMID 31679956.

- ^ Jacobs B, Dussor G (December 2016). "Neurovascular contributions to migraine: Moving beyond vasodilation". Neuroscience. 338: 130–144. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.012. PMC 5083225. PMID 27312704.

- ^ Mason BN, Russo AF (2018). "Vascular Contributions to Migraine: Time to Revisit?". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 12: 233. doi:10.3389/fncel.2018.00233. PMC 6088188. PMID 30127722.

- ^ Dodick DW, Gargus JJ (August 2008). "Why migraines strike". Scientific American. 299 (2): 56–63. Bibcode:2008SciAm.299b..56D. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0808-56. PMID 18666680.

- ^ Edvinsson L, Haanes KA (May 2020). "Views on migraine pathophysiology: Where does it start?". Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience. 8 (3): 120–127. doi:10.1111/ncn3.12356. ISSN 2049-4173. S2CID 214320892.

- ^ Do TP, Hougaard A, Dussor G, Brennan KC, Amin FM (January 2023). "Migraine attacks are of peripheral origin: the debate goes on". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 24 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/s10194-022-01538-1. PMC 9830833. PMID 36627561.

- ^ a b c d The Headaches, Chp. 28, pp. 269–72

- ^ a b c Olesen J, Burstein R, Ashina M, Tfelt-Hansen P (July 2009). "Origin of pain in migraine: evidence for peripheral sensitisation". The Lancet. Neurology. 8 (7): 679–90. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70090-0. PMID 19539239. S2CID 20452008.

- ^ Akerman S, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ (September 2011). "Diencephalic and brainstem mechanisms in migraine". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 12 (10): 570–84. doi:10.1038/nrn3057. PMID 21931334. S2CID 8472711.

- ^ Shevel E (March 2011). "The extracranial vascular theory of migraine--a great story confirmed by the facts". Headache. 51 (3): 409–417. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01844.x. PMID 21352215. S2CID 6939786.

- ^ a b Burnstock G (January 2016). "Purinergic Mechanisms and Pain". In Barrett JE (ed.). Pharmacological Mechanisms and the Modulation of Pain. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 75. pp. 91–137. doi:10.1016/bs.apha.2015.09.001. ISBN 9780128038833. PMID 26920010.

- ^ Davidoff R (14 February 2002). Migraine: Manifestations, Pathogenesis, and Management. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803135-2. Archived from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Lipton RB, Diener HC, Robbins MS, Garas SY, Patel K (October 2017). "Caffeine in the management of patients with headache". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 18 (1): 107. doi:10.1186/s10194-017-0806-2. PMC 5655397. PMID 29067618.

- ^ Hamel E (November 2007). "Serotonin and migraine: biology and clinical implications". Cephalalgia. 27 (11): 1293–300. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01476.x. PMID 17970989. S2CID 26543041.

- ^

- Lewis DW, Dorbad D (September 2000). "The utility of neuroimaging in the evaluation of children with migraine or chronic daily headache who have normal neurological examinations". Headache. 40 (8): 629–32. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.040008629.x. PMID 10971658. S2CID 14443890.

- Silberstein SD (September 2000). "Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 55 (6): 754–62. doi:10.1212/WNL.55.6.754. PMID 10993991.

- Medical Advisory Secretariat (2010). "Neuroimaging for the evaluation of chronic headaches: an evidence-based analysis". Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series. 10 (26): 1–57. PMC 3377587. PMID 23074404.

- ^ Cousins G, Hijazze S, Van de Laar FA, Fahey T (July–August 2011). "Diagnostic accuracy of the ID Migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Headache. 51 (7): 1140–8. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01916.x. PMID 21649653. S2CID 205684294.

- ^ "Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition". Cephalalgia. 38 (1): 1–211. January 2018. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202. PMID 29368949.

- ^ Nappi G (September 2005). "Introduction to the new International Classification of Headache Disorders". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 6 (4): 203–4. doi:10.1007/s10194-005-0185-y. PMC 3452009. PMID 16362664.

- ^ "Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition". Cephalalgia. 38 (1): 1–211. January 2018. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202. ISSN 0333-1024. PMID 29368949.

- ^ Negro A, Rocchietti-March M, Fiorillo M, Martelletti P (December 2011). "Chronic migraine: current concepts and ongoing treatments". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 15 (12): 1401–20. PMID 22288302.

- ^ a b c d Davidoff RA (2002). Migraine : manifestations, pathogenesis, and management (2 ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780195137057. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016.

- ^ Russell G, Abu-Arafeh I, Symon DN (2002). "Abdominal migraine: evidence for existence and treatment options". Paediatric Drugs. 4 (1): 1–8. doi:10.2165/00128072-200204010-00001. PMID 11817981. S2CID 12289726.

- ^ Lewis DW, Dorbad D (September 2000). "The utility of neuroimaging in the evaluation of children with migraine or chronic daily headache who have normal neurological examinations". Headache. 40 (8): 629–32. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.040008629.x. PMID 10971658. S2CID 14443890.

- ^ Silberstein SD (September 2000). "Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 55 (6): 754–62. doi:10.1212/WNL.55.6.754. PMID 10993991.

- ^ Medical Advisory Secretariat (2010). "Neuroimaging for the evaluation of chronic headaches: an evidence-based analysis". Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series. 10 (26): 1–57. PMC 3377587. PMID 23074404.

- ^ Chawla J, Lutsep HL (13 June 2023). "Migraine Headache Treatment & Management". Medscape. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Silberstein SD, Lee L, Gandhi K, Fitzgerald T, Bell J, Cohen JM (November 2018). "Health care Resource Utilization and Migraine Disability Along the Migraine Continuum Among Patients Treated for Migraine". Headache. 58 (10): 1579–1592. doi:10.1111/head.13421. PMID 30375650. S2CID 53114546.

- ^ a b "Migraine Information Page: Prognosis" Archived 10 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine, National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institutes of Health (US).

- ^ "Key facts and figures about migraine". The Migraine Trust. 2017. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ a b Brennan KC, Pietrobon D (March 2018). "A Systems Neuroscience Approach to Migraine". Neuron. 97 (5): 1004–1021. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.01.029. PMC 6402597. PMID 29518355.

- ^ World Health Organization (2008). "Disability classes for the Global Burden of Disease study" (table 8), The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update Archived 13 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, p 33.

- ^ a b c Schürks M, Rist PM, Bigal ME, Buring JE, Lipton RB, Kurth T (October 2009). "Migraine and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 339: b3914. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3914. PMC 2768778. PMID 19861375.

- ^ Kurth T, Chabriat H, Bousser MG (January 2012). "Migraine and stroke: a complex association with clinical implications". The Lancet. Neurology. 11 (1): 92–100. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70266-6. PMID 22172624. S2CID 31939284.

- ^ Rist PM, Diener HC, Kurth T, Schürks M (June 2011). "Migraine, migraine aura, and cervical artery dissection: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Cephalalgia. 31 (8): 886–96. doi:10.1177/0333102411401634. PMC 3303220. PMID 21511950.

- ^ Kurth T (March 2010). "The association of migraine with ischemic stroke". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 10 (2): 133–9. doi:10.1007/s11910-010-0098-2. PMID 20425238. S2CID 27227332.

- ^ Schürks M, Rist PM, Shapiro RE, Kurth T (September 2011). "Migraine and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Cephalalgia. 31 (12): 1301–14. doi:10.1177/0333102411415879. PMC 3175288. PMID 21803936.

- ^ Weinberger J (March 2007). "Stroke and migraine". Current Cardiology Reports. 9 (1): 13–9. doi:10.1007/s11886-007-0004-y. PMID 17362679. S2CID 46681674.

- ^ Hougaard A, Amin FM, Ashina M (June 2014). "Migraine and structural abnormalities in the brain". Current Opinion in Neurology. 27 (3): 309–14. doi:10.1097/wco.0000000000000086. PMID 24751961.

- ^ a b c Ferrari MD, Goadsby PJ, Burstein R, Kurth T, Ayata C, Charles A, et al. (January 2022). "Migraine". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 8 (1): 2. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00328-4. PMID 35027572. S2CID 245883895.

- ^ Chalmer MA, Kogelman LJ, Callesen I, Christensen CG, Techlo TR, Møller PL, et al. (June 2023). "Sex differences in clinical characteristics of migraine and its burden: a population-based study". European Journal of Neurology. 30 (6): 1774–1784. doi:10.1111/ene.15778. PMID 36905094.

- ^ Stovner LJ, Zwart JA, Hagen K, Terwindt GM, Pascual J (April 2006). "Epidemiology of headache in Europe". European Journal of Neurology. 13 (4): 333–45. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01184.x. PMID 16643310. S2CID 7490176.

- ^ Wang SJ (March 2003). "Epidemiology of migraine and other types of headache in Asia". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 3 (2): 104–8. doi:10.1007/s11910-003-0060-7. PMID 12583837. S2CID 24939546.

- ^ Natoli JL, Manack A, Dean B, Butler Q, Turkel CC, Stovner L, et al. (May 2010). "Global prevalence of chronic migraine: a systematic review". Cephalalgia. 30 (5): 599–609. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01941.x. PMID 19614702. S2CID 5328642.

- ^ Nappi RE, Sances G, Detaddei S, Ornati A, Chiovato L, Polatti F (June 2009). "Hormonal management of migraine at menopause". Menopause International. 15 (2): 82–6. doi:10.1258/mi.2009.009022. PMID 19465675. S2CID 23204921.

- ^ a b Miller N (2005). Walsh and Hoyt's clinical neuro-ophthalmology (6 ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1275. ISBN 9780781748117. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017.

- ^ Liddell HG, Scott R. "ἡμικρανία". A Greek-English Lexicon. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. on Perseus

- ^ Anderson K, Anderson LE, Glanze WD (1994). Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary (4 ed.). Mosby. p. 998. ISBN 978-0-8151-6111-0.

- ^ a b c d e Borsook D (2012). The migraine brain : imaging, structure, and function. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–11. ISBN 9780199754564. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ a b Waldman SD (2011). Pain management (2 ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 2122–2124. ISBN 9781437736038. Archived from the original on 23 August 2023. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Sex(ism), Drugs, and Migraines". Distillations. Science History Institute. 15 January 2019. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Margaret C, Simon M (2002). Human osteology : in archaeology and forensic science (Repr. ed.). Cambridge [etc.]: Cambridge University Press. p. 345. ISBN 9780521691468. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013.

- ^ Colen C (2008). Neurosurgery. Colen Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 9781935345039.

- ^ Daniel BT (2010). Migraine. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. p. 101. ISBN 9781449069629. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017.

- ^ Butticè C (April 2022). What you need to know about headaches. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-4408-7531-1. OCLC 1259297708. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b Tfelt-Hansen PC, Koehler PJ (May 2011). "One hundred years of migraine research: major clinical and scientific observations from 1910 to 2010". Headache. 51 (5): 752–78. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01892.x. PMID 21521208. S2CID 31940152.

- ^ Tfelt-Hansen P, Koehler P (2008). "History of the Use of Ergotamine and Dihydroergotamine in Migraine from 1906 and Onward". Cephalalgia. 28 (8): 877–886. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01578.x. PMID 18460007.

- ^ a b c Stovner LJ, Andrée C (June 2008). "Impact of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 9 (3): 139–46. doi:10.1007/s10194-008-0038-6. PMC 2386850. PMID 18418547.

- ^ a b Mennini FS, Gitto L, Martelletti P (August 2008). "Improving care through health economics analyses: cost of illness and headache". The Journal of Headache and Pain. 9 (4): 199–206. doi:10.1007/s10194-008-0051-9. PMC 3451939. PMID 18604472.

- ^ Magis D, Jensen R, Schoenen J (June 2012). "Neurostimulation therapies for primary headache disorders: present and future". Current Opinion in Neurology. 25 (3): 269–76. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283532023. PMID 22543428.

- ^ Jürgens TP, Leone M (June 2013). "Pearls and pitfalls: neurostimulation in headache". Cephalalgia. 33 (8): 512–25. doi:10.1177/0333102413483933. PMID 23671249. S2CID 42537455.

- ^ Barbanti P, Fofi L, Aurilia C, Egeo G, Caprio M (May 2017). "Ketogenic diet in migraine: rationale, findings and perspectives". Neurological Sciences (Review). 38 (Suppl 1): 111–115. doi:10.1007/s10072-017-2889-6. PMID 28527061. S2CID 3805337.

- ^ Gross EC, Klement RJ, Schoenen J, D'Agostino DP, Fischer D (April 2019). "Potential Protective Mechanisms of Ketone Bodies in Migraine Prevention". Nutrients. 11 (4): 811. doi:10.3390/nu11040811. PMC 6520671. PMID 30974836.

- ^ Artero-Morales M, González-Rodríguez S, Ferrer-Montiel A (2018). "TRP Channels as Potential Targets for Sex-Related Differences in Migraine Pain". Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 5: 73. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2018.00073. PMC 6102492. PMID 30155469.

- ^ Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Celentano DD, Reed ML (January 1992). "Prevalence of migraine headache in the United States. Relation to age, income, race, and other sociodemographic factors". JAMA. 267 (1): 64–69. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480010072027. PMID 1727198.

- ^ "Speeding Progress in Migraine Requires Unraveling Sex Differences". SWHR. 28 August 2018. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Smith L (11 March 2021). Hamilton K (ed.). "Migraine in Women Needs More Sex-Specific Research". Migraine Again. Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Schroeder RA, Brandes J, Buse DC, Calhoun A, Eikermann-Haerter K, Golden K, et al. (August 2018). "Sex and Gender Differences in Migraine-Evaluating Knowledge Gaps". Journal of Women's Health. 27 (8): 965–973. doi:10.1089/jwh.2018.7274. PMID 30129895. S2CID 52048078.

Further reading

[edit]- Ashina M (November 2020). Ropper AH (ed.). "Migraine". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (19): 1866–1876. doi:10.1056/nejmra1915327. PMID 33211930. S2CID 227078662.

- Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Billinghurst L, Potrebic S, Gersz EM, Gloss D, et al. (September 2019). "Practice guideline update summary: Pharmacologic treatment for pediatric migraine prevention: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 93 (11): 500–509. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008105. PMC 6746206. PMID 31413170.

- Oskoui M, Pringsheim T, Holler-Managan Y, Potrebic S, Billinghurst L, Gloss D, et al. (September 2019). "Practice guideline update summary: Acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society". Neurology. 93 (11): 487–499. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000008095. PMID 31413171. S2CID 199662718.

External links

[edit]| External audio | |

|---|---|

Diseases of the nervous system, primarily CNS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brain/ encephalopathy |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Both/either |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Primary |

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary |

| ||||||||

| ICHD 13 | |||||||||

| Other | |||||||||

Antimigraine preparations (N02C) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analgesic/abortive |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Prophylactic |

| ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||