| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanomaterials |

|---|

|

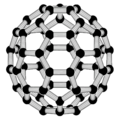

| Carbon nanotubes |

| Fullerenes |

| Other nanoparticles |

| Nanostructured materials |

Nanocellulose is a term referring to a familly of cellulosic materials that have a nanoscale dimension. Examples of nanocellulosic materials are microfibrilated cellulose, cellulose nanofibers or cellulose nanocrystals. Nanocellulose may be obtained from natural cellulose fibers through different production processes. This family of materials possess various interesting properties for a wide range of potential applications.

Microfibrilated cellulose (MFC) is a type of nanocellulose that is more heterogeneous than cellulose nanofibers or nanocrystals as it contains a mixture of nano- and micron-scale particles. The term is sometimes misused to refer to cellulose nanofibers instead.[1]

Cellulose nanofibers (CNF), also called nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), are nanosized cellulose fibrils with a high aspect ratio (length to width ratio). Typical fibril widths are 5–20 nanometers with a wide range of lengths, typically several micrometers.

The fibrils are isolated from any cellulose containing source including wood-based fibers (pulp fibers) through high-pressure, high temperature and high velocity impact homogenization, grinding or microfluidization (see manufacture below).[2][3][4]

Cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs), or nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC), can also be referred to as cellulose whiskers or cellulose nanowhiskers, though these last two terms are less used today. CNCs are rodlike highly crystalline (relative crystallinity index above 75%) nanoparticles that are shorter than CNFs (typically 100 to 1000 nanometers).[5]

Nanochitin is similar in its nanostructure to cellulose nanocrystals but extracted from chitin.

The discovery of nanocellulose can be traced back to late 1940s studies on the hydrolysis of cellulose fibers. Eventually it was noticed that cellulose hydrolysis seemed to occur preferentially at some "disordered" intercrystalline portions of the fibers, leaving unhydrolyzed residual material.[6] Further studies showed that the unhydrolyzed material was made of colloidally stable and highly crystalline nanorods particles that were later named CNCs.[7][8][9]

The terminology microfibrillated cellulose (MFC) was introduced by Turbak, Snyder and Sandberg in the 1980s at the ITT Rayonier labs in Shelton, Washington,[10] to describe a product prepared as a gel type material by passing wood pulp through a Gaulin type milk homogenizer at high temperatures and high pressures followed by ejection impact against a hard surface.

The terminology nanocellulose first appeared publicly in the early 1980s when a number of patents and publications were issued to ITT Rayonier on a new nanocellulose composition of matter. In later work, F. W. Herrick at ITT Rayonier Eastern Research Division (ERD) Lab in Whippany also published work on making a dry powder form of the gel.[11] Rayonier has produced purified pulps.[12][13][14] Rayonier gave free license to whoever wanted to pursue this new use for cellulose. Rayonier, as a company, never pursued scale-up. Rather, Turbak et al. pursued 1) finding new uses for the MFC. These included using MFC as a thickener and binder in foods, cosmetics, paper formation, textiles, nonwovens, etc. and 2) evaluate swelling and other techniques for lowering the energy requirements for MFC production.[15] After ITT closed the Rayonier Whippany Labs in 1983–84, Herric worked on making a dry powder form of MFC at the Rayonier labs in Shelton, Washington.[11]

In the mid-1990s, the group of Taniguchi and co-workers and later Yano and co-workers pursued the effort in Japan.[16]

Innventia AB (Sweden) established the first MFC pilot production plant 2010.[17]

Nanocellulose can be prepared from any cellulose source material including wood, cotton, agricultural[18] or household wastes,[19] algae,[20] bacteria or tunicate. Wood, in the form of wood pulp is currently the most commonly used starting material for the industrial production of nanocellulosic materials.

The nanocellulose fibrils may be isolated from the wood-based fibers using mechanical methods which expose the pulp to high shear forces, ripping the larger wood-fibres apart into nanofibers. For this purpose, high-pressure homogenizers, grinders or microfluidizers can be used.[citation needed] The homogenizers are used to delaminate the cell walls of the fibers and liberate the nanosized fibrils. This process consumes very large amounts of energy and values over 30 MWh/tonne are not uncommon.[citation needed]

To address this problem, sometimes enzymatic/mechanical pre-treatments[21] and introduction of charged groups for example through carboxymethylation[22] or TEMPO-mediated oxidation are used.[23] These pre-treatments can decrease energy consumption below 1 MWh/tonne.[24] "Nitro-oxidation" has been developed to prepare carboxycellulose nanofibers directly from raw plant biomass. Owing to fewer processing steps to extract nanocellulose, the nitro-oxidation method has been found to be a cost-effective, less-chemically oriented and efficient method to extract carboxycellulose nanofibers.[25][26] Functionalized nanofibers obtained using nitro-oxidation have been found to be an excellent substrate to remove heavy metal ion impurities such as lead,[27] cadmium,[28] and uranium.[29]

Spherical shaped carboxycellulose nanoparticles prepared by nitric acid-phosphoric acid treatment are stable in dispersion in its non-ionic form.[30] In April 2013 breakthroughs in nanocellulose production, by algae, were announced at an American Chemical Society conference, by speaker R. Malcolm Brown, Jr., Ph.D, who has pioneered research in the field for more than 40 years, spoke at the First International Symposium on Nanocellulose, part of the American Chemical Society meeting. Genes from the family of bacteria that produce vinegar, Kombucha tea and nata de coco have become stars in a project — which scientists said has reached an advanced stage - that would turn algae into solar-powered factories for producing the “wonder material” nanocellulose.[31]

A chemo-mechanical process for production of nanocellulose from cotton linters has been demonstrated with a capacity of 10 kg per day.[32]

CNCs are formed by the acid hydrolysis of native cellulose fibers commonly using sulfuric or hydrochloric acid. Disordered sections of native cellulose are hydrolysed and after careful timing, crystalline sections can be retrieved from the acid solution by centrifugation and washing. Their dimensions depend on the native cellulose source material, and hydrolysis conditions.[33]

The ultrastructure of nanocellulose derived from various sources has been extensively studied. Techniques such as transmission electron microscopy (TEM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), wide angle X-ray scattering (WAXS), small incidence angle X-ray diffraction and solid state 13C cross-polarization magic angle spinning (CP/MAS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and spectroscopy have been used to characterize typically dried nanocellulose morphology.[34]

A combination of microscopic techniques with image analysis can provide information on fibril widths, it is more difficult to determine fibril lengths, because of entanglements and difficulties in identifying both ends of individual nanofibrils.[35][36][page needed] Also, nanocellulose suspensions may not be homogeneous and can consist of various structural components, including cellulose nanofibrils and nanofibril bundles.[37]

In a study of enzymatically pre-treated nanocellulose fibrils in a suspension the size and size-distribution were established using cryo-TEM. The fibrils were found to be rather mono-dispersed mostly with a diameter of ca. 5 nm although occasionally thicker fibril bundles were present.[21] By combining ultrasonication with an "oxidation pretreatment", cellulose microfibrils with a lateral dimension below 1 nm has been observed by AFM. The lower end of the thickness dimension is around 0.4 nm, which is related to the thickness of a cellulose monolayer sheet.[38]

Aggregate widths can be determined by CP/MAS NMR developed by Innventia AB, Sweden, which also has been demonstrated to work for nanocellulose (enzymatic pre-treatment). An average width of 17 nm has been measured with the NMR-method, which corresponds well with SEM and TEM. Using TEM, values of 15 nm have been reported for nanocellulose from carboxymethylated pulp. However, thinner fibrils can also be detected. Wågberg et al. reported fibril widths of 5–15 nm for a nanocellulose with a charge density of about 0.5 meq./g.[22] The group of Isogai reported fibril widths of 3–5 nm for TEMPO-oxidized cellulose having a charge density of 1.5 meq./g.[39]

Pulp chemistry has a significant influence on nanocellulose microstructure. Carboxymethylation increases the numbers of charged groups on the fibril surfaces, making the fibrils easier to liberate and results in smaller and more uniform fibril widths (5–15 nm) compared to enzymatically pre-treated nanocellulose, where the fibril widths were 10–30 nm.[40] The degree of crystallinity and crystal structure of nanocellulose. Nanocellulose exhibits cellulose crystal I organization and the degree of crystallinity is unchanged by the preparation of the nanocellulose. Typical values for the degree of crystallinity were around 63%.[40]

The rheology of nanocellulose dispersions has been investigated.[41][21] and revealed that the storage and loss modulus were independent of the angular frequency at all nanocellulose concentrations between 0.125% to 5.9%. The storage modulus values are particularly high (104 Pa at 3% concentration)[21] compared to results for CNCs (102 Pa at 3% concentration).[41] There is also a strong concentration dependence as the storage modulus increases 5 orders of magnitude if the concentration is increased from 0.125% to 5.9%. Nanocellulose gels are also highly shear thinning (the viscosity is lost upon introduction of the shear forces). The shear-thinning behaviour is particularly useful in a range of different coating applications.[21]

It is pseudo-plastic and exhibits thixotropy, the property of certain gels or fluids that are thick (viscous) under normal conditions, but become less viscous when shaken or agitated. When the shearing forces are removed the gel regains much of its original state.

Crystalline cellulose has a stiffness about 140–220 GPa, comparable with that of Kevlar and better than that of glass fiber, both of which are used commercially to reinforce plastics. Films made from nanocellulose have high strength (over 200 MPa), high stiffness (around 20 GPa)[42] but lack of high strain[clarification needed] (12%). Its strength/weight ratio is 8 times that of stainless steel.[43] Fibers made from nanocellulose have high strength (up to 1.57 GPa) and stiffness (up to 86 GPa).[44]

In semi-crystalline polymers, the crystalline regions are considered to be gas impermeable. Due to relatively high crystallinity,[40] in combination with the ability of the nanofibers to form a dense network held together by strong inter-fibrillar bonds (high cohesive energy density), it has been suggested that nanocellulose might act as a barrier material.[39][45][46] Although the number of reported oxygen permeability values are limited, reports attribute high oxygen barrier properties to nanocellulose films. One study reported an oxygen permeability of 0.0006 (cm3 μm)/(m2 day kPa) for a ca. 5 μm thin nanocellulose film at 23 °C and 0% RH.[45] In a related study, a more than 700-fold decrease in oxygen permeability of a polylactide (PLA) film when a nanocellulose layer was added to the PLA surface was reported.[39]

The influence of nanocellulose film density and porosity on film oxygen permeability has been explored.[47] Some authors have reported significant porosity in nanocellulose films,[48][42][49] which seems to be in contradiction with high oxygen barrier properties, whereas Aulin et al.[45] measured a nanocellulose film density close to density of crystalline cellulose (cellulose Iß crystal structure, 1.63 g/cm3)[50] indicating a very dense film with a porosity close to zero.

Changing the surface functionality of the cellulose nanoparticle can also affect the permeability of nanocellulose films. Films constituted of negatively charged CNCs could effectively reduce permeation of negatively charged ions, while leaving neutral ions virtually unaffected. Positively charged ions were found to accumulate in the membrane.[51]

Multi-parametric surface plasmon resonance is one of the methods to study barrier properties of natural, modified or coated nanocellulose. The different antifouling, moisture, solvent, antimicrobial barrier formulation quality can be measured on the nanoscale. The adsorption kinetics as well as the degree of swelling can be measured in real-time and label-free.[52][53]

Owed to their anisotropic shape and surface charge, nanocelluloses (mostly rigid CNCs) have a high excluded volume and self-assemble into cholesteric liquid crystals beyond a critical volume fraction.[54] Nanocellulose liquid crystals are left-handed due to the right-handed twist on particle level.[55] Nanocellulose phase behavior is susceptible to ionic charge screening. An increase in ionic strength induces the arrest of nanocellulose dispersions into attractive glasses.[56] At further increasing ionic strength, nanocelluloses aggregate into hydrogels.[57] The interactions within nanocelluloses are weak and reversible, wherefore nanocellulose suspensions and hydrogels are self-healing and may be applied as injectable materials[58] or 3D printing inks.[59]

Nanocellulose can also be used to make aerogels/foams, either homogeneously or in composite formulations. Nanocellulose-based foams are being studied for packaging applications in order to replace polystyrene-based foams. Svagan et al. showed that nanocellulose has the ability to reinforce starch foams by using a freeze-drying technique.[60] The advantage of using nanocellulose instead of wood-based pulp fibers is that the nanofibrils can reinforce the thin cells in the starch foam. Moreover, it is possible to prepare pure nanocellulose aerogels applying various freeze-drying and super critical CO

2 drying techniques. Aerogels and foams can be used as porous templates.[61][62] Tough ultra-high porosity foams prepared from cellulose I nanofibril suspensions were studied by Sehaqui et al. a wide range of mechanical properties including compression was obtained by controlling density and nanofibril interaction in the foams.[63] CNCs could also be made to gel in water under low power sonication giving rise to aerogels with the highest reported surface area (>600m2/g) and lowest shrinkage during drying (6.5%) of cellulose aerogels.[62] In another study by Aulin et al.,[64] the formation of structured porous aerogels of nanocellulose by freeze-drying was demonstrated. The density and surface texture of the aerogels was tuned by selecting the concentration of the nanocellulose dispersions before freeze-drying. Chemical vapour deposition of a fluorinated silane was used to uniformly coat the aerogel to tune their wetting properties towards non-polar liquids/oils. The authors demonstrated that it is possible to switch the wettability behaviour of the cellulose surfaces between super-wetting and super-repellent, using different scales of roughness and porosity created by the freeze-drying technique and change of concentration of the nanocellulose dispersion. Structured porous cellulose foams can however also be obtained by utilizing the freeze-drying technique on cellulose generated by Gluconobacter strains of bacteria, which bio-synthesize open porous networks of cellulose fibers with relatively large amounts of nanofibrils dispersed inside. Olsson et al.[65] demonstrated that these networks can be further impregnated with metalhydroxide/oxide precursors, which can readily be transformed into grafted magnetic nanoparticles along the cellulose nanofibers. The magnetic cellulose foam may allow for a number of novel applications of nanocellulose and the first remotely actuated magnetic super sponges absorbing 1 gram of water within a 60 mg cellulose aerogel foam were reported. Notably, these highly porous foams (>98% air) can be compressed into strong magnetic nanopapers, which may find use as functional membranes in various applications.

Nanocelluloses can stabilize emulsions and foams by a Pickering mechanism, i.e. they adsorb at the oil-water or air-water interface and prevent their energetic unfavorable contact. Nanocelluloses form oil-in-water emulsions with a droplet size in the range of 4-10 μm that are stable for months and can resist high temperatures and changes in pH.[66][67] Nanocelluloses decrease the oil-water interface tension[68] and their surface charge induces electrostatic repulsion within emulsion droplets. Upon salt-induced charge screening the droplets aggregate but do not undergo coalescence, indicating strong steric stabilization.[69] The emulsion droplets even remain stable in the human stomach and resist gastric lipolysis, thereby delaying lipid absorption and satiation.[70][71] In contrast to emulsions, native nanocelluloses are generally not suitable for the Pickering stabilization of foams, which is attributed to their primarily hydrophilic surface properties that results in an unfavorable contact angle below 90° (they are preferably wetted by the aqueous phase).[72] Using hydrophobic surface modifications or polymer grafting, the surface hydrophobicity and contact angle of nanocelluloses can be increased, allowing also the Pickering stabilization of foams.[73] By further increasing the surface hydrophobicity, inverse water-in-oil emulsions can be obtained, which denotes a contact angle higher than 90°.[74][75] It was further demonstrated that nanocelluloses can stabilize water-in-water emulsions in presence of two incompatible water-soluble polymers.[76]

A bottom up approach can be used to create a high-performance bulk material with low density, high strength and toughness, and great thermal dimensional stability. Cellulose nanofiber hydrogel is created by biosynthesis. The hydrogels can then be treated with a polymer solution or by surface modification and then are hot-pressed at 80 °C. The result is bulk material with excellent machinability. “The ultrafine nanofiber network structure in CNFP results in more extensive hydrogen bonding, the high in-plane orientation, and “three way branching points” of the microfibril networks”.[77] This structure gives CNFP its high strength by distributing stress and adding barriers to crack formation and propagation. The weak link in this structure is bond between the pressed layers which can lead to delamination. To reduce delamination, the hydrogel can be treated with silicic acid, which creates strong covalent cross-links between layers during hot pressing.[77]

The surface modification of nanocellulose is currently receiving a large amount of attention.[78] Nanocellulose displays a high concentration of hydroxyl groups at the surface which can be reacted. However, hydrogen bonding strongly affects the reactivity of the surface hydroxyl groups. In addition, impurities at the surface of nanocellulose such as glucosidic and lignin fragments need to be removed before surface modification to obtain acceptable reproducibility between different batches.[79]

Processing of nanocellulose does not cause significant exposure to fine particles during friction grinding or spray drying. No evidence of inflammatory effects or cytotoxicity on mouse or human macrophages can be observed after exposure to nanocellulose. The results of toxicity studies suggest that nanocellulose is not cytotoxic and does not cause any effects on inflammatory system in macrophages. In addition, nanocellulose is not acutely toxic to Vibrio fischeri in environmentally relevant concentrations.[80]

Despite intensified research on oral food or pharmaceutical formulations containing nanocelluloses they are not generally recognized as safe. Nanocelluloses were demonstrated to exhibit limited toxicity and oxidative stress in in vitro intestinal epithelium[81][82][83] or animal models.[84][85][86]

The properties of nanocellulose (e.g. mechanical properties, film-forming properties, viscosity etc.) makes it an interesting material for many applications.[87]

In the area of paper and paperboard manufacture, nanocelluloses are expected to enhance the fiber-fiber bond strength and, hence, have a strong reinforcement effect on paper materials.[90][91][92] Nanocellulose may be useful as a barrier in grease-proof type of papers and as a wet-end additive to enhance retention, dry and wet strength in commodity type of paper and board products.[93][94][95][96] It has been shown that applying CNF as a coating material on the surface of paper and paperboard improves the barrier properties, especially air resistance[97] and grease/oil resistance.[97][98][99] It also enhances the structure properties of paperboards (smoother surface).[100] Very high viscosity of MFC/CNF suspensions at low solids content limits the type of coating techniques that can be utilized to apply these suspensions onto paper/paperboard. Some of the coating methods utilized for MFC surface application onto paper/paperboard have been rod coating,[99] size press,[98] spray coating,[101] foam coating [102] and slot-die coating.[97] Wet-end surface application of mineral pigments and MFC mixture to improve barrier, mechanical and printing properties of paperboard are also being explored.[103]

Nanocellulose can be used to prepare flexible and optically transparent paper. Such paper is an attractive substrate for electronic devices because it is recyclable, compatible with biological objects, and easily biodegrades.[89]

As described above the properties of the nanocellulose makes an interesting material for reinforcing plastics. Nanocellulose can be spun into filaments that are stronger and stiffer than spider silk.[104][105] Nanocellulose has been reported to improve the mechanical properties of thermosetting resins, starch-based matrixes, soy protein, rubber latex, poly(lactide). Hybrid cellulose nanofibrils-clay minerals composites present interesting mechanical, gas barrier and fire retardancy properties.[106] The composite applications may be for use as coatings and films,[107] paints, foams, packaging.

Nanocellulose can be used as a low calorie replacement for carbohydrate additives used as thickeners, flavour carriers, and suspension stabilizers in a wide variety of food products.[108] It is useful for producing fillings, crushes, chips, wafers, soups, gravies, puddings etc. The food applications arise from the rheological behaviour of the nanocellulose gel.

Applications in this field include: super water absorbent material (e.g. for incontinence pads material), nanocellulose used together with super absorbent polymers, nanocellulose in tissue, non-woven products or absorbent structures and as antimicrobial films. [citation needed]

Nanocellulose has potential applications in the general area of emulsion and dispersion applications in other fields.[109][110]

The use of nanocellulose in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals has been suggested:

Nanocellulose can pave the way for a new type of "bio-based electronics" where interactive materials are mixed with nanocellulose to enable the creation of new interactive fibers, films, aerogels, hydrogels and papers.[112] E.g. nanocellulose mixed with conducting polymers such as PEDOT:PSS show synergetic effects resulting in extraordinary[113] mixed electronic and ionic conductivity, which is important for energy storage applications. Filaments spun from a mix of nanocellulose and carbon nanotubes show good conductivity and mechanical properties.[114] Nanocellulose aerogels decorated with carbon nanotubes can be constructed into robust compressible 3D supercapacitor devices.[115][116] Structures from nanocellulose can be turned into bio-based triboelectric generators[117] and sensors.

Cellulose nanocrystals have shown the possibility to self organize into chiral nematic structures[118] with angle-dependent iridescent colours. It is thus possible to manufacture totally bio-based pigments and glitters, films including sequins having a metallic glare and a small footprint compared to fossil-based alternatives.