In politics, a partition is a change of political borders cutting through at least one territory considered a homeland by some community.[1]

In politics, a partition is a change of political borders cutting through at least one territory considered a homeland by some community.[1]

Brendan O'Leary distinguishes partition from secession, which take place within existing recognized political units.[1]

For Arie Dubnov and Laura Robson, partition is the physical division of territory along ethno-religious lines into separate nation-states. They locate partition in the context of post-World War I peacebuilding and the "new conversations surrounding ethnicity, nationhood, and citizenship" that emerged out of it.[2] The post-war agreements, such as the League of Nations mandate system, promoted "a new political language of ethnic separatism as a central aspect of national self-determination, while protecting and disguising continuities and even expansions of French and, especially, British imperial powers.[3]

While Ranabir Samaddar identifies the Dissolution of Austria-Hungary as an example of partition, resulting from competing national ambitions, he agrees partition gained prominence following World War I, particularly with the division of the Ottoman Empire. By this point, he argues ethnicity had become the primary justification of border proposals.[4]

After World War II, Dubnov and Robson argue partition transformed from "an imperial tactic into an organizing principle" of world diplomacy".[5]

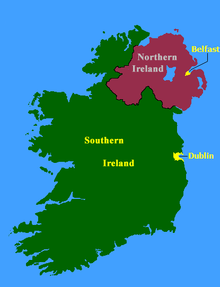

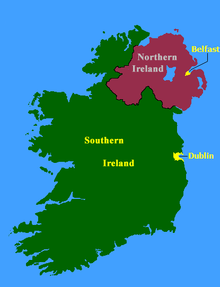

Scholarship has closely linked partition to violence. Tracing the precedent for the Partition of Ireland in population resettlements across former Ottoman Empire territories and the making of national 'majorities' and 'minorities', Dubnov and Robson emphasise how partitions after Ireland contained proposals to transfer "inconvenient populations in addition to forcible territorial division into separate states", which they note had violent consequences for local actors who were devolved the task of "carving out physically separate political entities on the ground and making them ethnically homogenous".[6]

T.G. Fraser notes how Britain proposed partition in both Ireland and Palestine as a method of resolving conflict between competing national groups, but in neither case did it end communal violence. Rather, Fraser argues, partition merely gave these conflicts a "new dimension".[7]

Similarly, A. Dirk Moses asserts partition does not "so much solve minority issues as deposit them into different containers as minority issues reappear in partitioned units", rejecting what he calls "divine cartographies" that seek to "neatly map peoples as naturally emplaced in their homelands" for disregarding the heterogeneous reality of identity in the real world.[8]

Daniel Posner has argued that partitions of diverse communities into homogenous communities is unlikely to solve problems of communal conflict, as the boundary changes will alter the actors' incentives and give rise to new cleavages.[9] For example, while the Muslim and Hindu cleavages might have been the most salient amid the Indian independence movement, the creation of a religiously homogenous Hindu state (India) and a religiously homogeneous Muslim state (Pakistan) created new social cleavages on lines other than religion in both of those states.[9] Posner writes that relatively homogenous countries can be more violence-prone than countries with a large number of evenly matched ethnic groups.[10]

Notable examples are: (See Category:Partition)