The Greek gymnasium of Sardis | |

| Alternative name | Sardes |

|---|---|

| Location | Sart, Manisa Province, Turkey |

| Region | Lydia |

| Coordinates | 38°29′18″N 28°02′25″E / 38.48833°N 28.04028°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | Settled by 1500 BC, major city by 600 BC |

| Abandoned | Around 1402 AD |

| Cultures | Seha River Land, Lydian, Greek, Persian, Roman, Byzantine |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1910–1914, 1922, 1958–present |

| Archaeologists | Howard Crosby Butler, G.M.A. Hanfmann, Crawford H. Greenewalt Jr., Nicholas Cahill |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | sardisexpedition |

Sardis (/ˈsɑːrdɪs/ SAR-diss) or Sardes (/ˈsɑːrdiːs/ SAR-deess; Lydian: 𐤳𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣, romanized: Šfard; Ancient Greek: Σάρδεις, romanized: Sárdeis; Old Persian: Sparda) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Persian satrapy of Lydia and later a major center of Hellenistic and Byzantine culture. Now an active archaeological site, it is located in modern day Turkey, in Manisa Province near the town of Sart.

History

[edit]Sardis was occupied for at least 3500 years. In that time, it fluctuated between a wealthy city of international importance and a collection of modest hamlets.[1](pp1114–1115)

Early settlement

[edit]

Sardis was settled before 1500 BC. However, the size and nature of early settlement is not known since only small extramural portions of these layers have been excavated. Evidence of occupation consists largely of Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age pottery which shows affinities with Mycenaean Greece and the Hittites. No early monumental architecture had been found as of 2011.[1](pp1114–1116)[2]

The site may have been occupied as early as the Neolithic, as evidenced by scattered finds of early ceramic fragments. However, these were found out of context, so no clear conclusions can be drawn. Early Bronze Age cemeteries were found 7 miles away along Lake Marmara, near elite graves of the later Lydian and Persian periods.[1](p1116)[2]

In the Late Bronze Age, the site would have been in the territory of the Seha River Land, whose capital is thought to have been located at nearby Kaymakçı. Hittite texts record that Seha was originally part of Arzawa, a macrokingdom which the Hittite king Mursili II defeated and partitioned. After that time, Seha became a vassal state of the Hittites and served as an important intermediary with the Mycenaean Greeks. The relationship between the people of Seha and the later Lydians is unclear, since there is evidence of both cultural continuity and disruption in the region.[2] Neither the term "Sardis" nor its alleged earlier name of "Hyde" (in Ancient Greek, which may have reflected a Hittite name "Uda") appears in any extant Hittite text.[1](pp1115–1116)

Lydian Period

[edit]

In the seventh century BC, Sardis became the capital city of Lydia. From there, kings such as Croesus ruled an empire that reached as far as the Halys River in the east. The city itself covered 108 hectares including extramural areas and was protected by walls thirty meters thick. The acropolis was terraced with white ashlar masonry to tame the naturally irregular mountainside. Visitors could spot the site from a distance by the three enormous burial tumuli at Bin Tepe.[1](pp1116–118)

The city's layout and organization is only partly known at present. To the north/northwest, the city had a large extramural zone with residential, commercial, and industrial areas. Settlement extended to the Pactolus Stream, near which archaeologists have found the remains of work installations where alluvial metals were processed.[1](p1117)

Multiroom houses around the site match Herodotus's description of fieldstone and mudbrick construction. Most houses had roofs of clay and straw while wealthy residents had roof tiles, similar to public buildings. Houses often have identifiable courtyards and food preparation areas but no complete house has been excavated so few generalizations can be drawn about Sardian houses' internal layout.[1](pp-1118-1120)

Religious remains include a modest altar which may have been dedicated to Cybele, given a pottery fragment found there with her name on it.[1](p1118) A possible sanctuary to Artemis was found elsewhere in the site, whose remains include marble statues of lions. [1](p1117) Vernacular worship is evidence in extramural areas by dinner servies buried as offerings.[1](p1117)

Textual evidence regarding Lydian-era Sardis include Pliny's account of a mudbrick building that had allegedly been the palace of Croesus and was still there in his own time.[1](p1117)

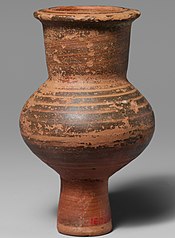

The material culture of Sardis is largely a distinctive twist on Anatolian and Aegean styles. The city's artisans seemed to specialize in glyptic art including seals and jewelry. Their pottery blended Aegean and Anatolian pottery styles, in addition to distinctive twists which included the lydion shape and decorative techniques known as streaky-glaze and marbled-glaze. Narrative scenes on Sardian pottery are rare. Imported Greek pottery attests to the Lydians' "Hellenophile attitude" commented on by contemporary Greek writers. While those Greek authors were in turn impressed by Lydians' music and textiles, these aspects of Lydian culture are not visible in the archaeological record.[1](p1124)

Destruction by Cyrus the Great

[edit]Sardis was conquered by Cyrus the Great around 547 BC. Having defeated the Lydian king Croesus at the Battle of Pteria and Battle of Thymbra, the Persians followed the retreating army back to Sardis and sacked it after a brief siege.[3] [4][1](pp1115, 1120) Details of this event are largely known from Herodotus's semi-mythicized account, but the destruction is highly visible in the archaeological record. In the words of excavator Nicholas Cahill:

It is rare that an important and well-known historical event is so vividly preserved in the archaeological record, but the destruction of Cyrus left clear and dramatic remains throughout the city.[4]

The city's fortifications burned in a massive fire that spread to parts of the adjoining residential areas. Wooden structures and objects inside buildings were reduced to charcoal. Mudbrick from the fortifications were toppled over on adjacent structures, preventing looting and salvage and thus preserving their remains.[4]

Skeletons were found buried haphazardly among the debris, including those of Lydian soldiers who died violently. One soldier's forearm bones had been snapped, likely a parry fracture indicating a failed attempt to counter the head injuries that killed him. A partly healed rib fracture suggests he was still recovering from an earlier injury during the battle. In a destroyed house, archaeologists found the partial skeleton of an arthritic man in his forties. The skeleton was so badly burned that archaeologists cannot determine whether it was deliberately mutilated or if the missing bones were carried away by animals.[4]

Arrowheads and other weaponry turn up in debris all around the city, suggesting a major battle in the streets. The varying styles suggest the mixed background of both armies involved. Household implements such as iron spits and small sickles were found mixed in with ordinary weapons of war, suggesting that civilians attempted to defend themselves during the sack.[4]

Persian Period

[edit]

After the destruction, Sardis was rebuilt and continued to be an important and prosperous city. Though it was never again the capital of an independent state, it did serve as the capital for the satrapy of Sparda and formed the end station of the Persian Royal Road which began in Persepolis. It acted as a gateway to the Greek world, and was visited by notable Greek leaders such as Lysander and Alcibiades, as well as the Persian kings Darius I and Xerxes.[1](pp1120–1122)[5]

Relatively little of Persian Sardis is visible in the archaeological record. The city may even have been rebuilt outside the limits of the Lydian-era walls, as evidenced by authors such as Herodotus who place the Persian era central district along the Pactolus stream.[6] The material culture of the city was largely continuous with the Lydian era, to the point that it can be hard to precisely date artifacts based on style.[1](pp1120–1122)

Notable developments of this period include adoption of the Aramaic script alongside the Lydian alphabet and the "Achaemenid bowl" pottery shape. [1](pp1120–1122) Jewelry of the period shows Persian-Anatolian cultural hybridization. In particular, jewelers turned to semi-precious stones and colored frit due to a Persian prohibition on gold jewelry among the priestly class. Similarly, knobbed pins and fibulae disappear from the archaeological record, reflecting changes in the garments with which they would have been used.[7]

Buildings from this era include a possible predecessor of the later temple to Artemis as well as a possible sanctuary of Zeus. Textual evidence suggests that the city was known for its paradisoi as well as orchards and hunting parks built by Tissaphernes and Cyrus the Younger[1](p1122) Burials of this period include enormous tumuli with extensive grave goods.[6]

In 499 BC, Sardis was attacked and burned by the Ionians as part of the Ionian Revolt against Persian rule. The subsequent destruction of mainland Greek cities was said to be retribution for this attack. When Themistocles later visited Sardis, he came across a votive statue he had personally dedicated at Athens, and requested its return.[6]

Hellenistic and Byzantine Sardis

[edit]

In 334 BC, Sardis was conquered by Alexander the Great. The city was surrendered without a fight, the local satrap having been killed during the Persian defeat at Granikos. After taking power, Alexander restored earlier Lydian customs and laws. For the next two centuries, the city passed between Hellenistic rulers including Antigonus Monophthalmos, Lysimachus, the Seleucids, and the Attalids. It was besieged by Seleucus I in 281 BC and by Antiochus III in 215-213 BC, but neither succeeded at breaching the acropolis, regarded as the strongest fortified place in the world. The city sometimes served as a royal residence, but was itself governed by an assembly. [1](p1123)[5]

In this era, the city took on a strong Greek character. The Greek language replaces the Lydian language in most inscriptions, and major buildings were constructed in Greek architectural styles to meet the needs of Greek cultural institutions. These new buildings included a prytaneion, gymnasion, theater, hippodrome, as well as the massive Temple of Artemis still visible to modern visitors. Jews were settled at Sardis by the Hellenistic king Antiochos III, where they built the Sardis Synagogue and formed a community which continued for much of late antiquity.[1](p1123)[5]

In 129 BC, Sardis passed to the Romans, under whom it continued its prosperity and political importance as part of the province of Asia. The city received three neocorate honors and was granted ten million sesterces as well as a temporary tax exemption to help it recover after a devastating earthquake in 17 AD.[1](p1123)[8][5]

Sardis had an early Christian community and is referred to in the New Testament as one of the seven churches of Asia. In the Book of Revelation, Jesus refers to the Sardians as not finishing what they started, being about image rather than substance.[9][better source needed]

Later, trade and the organization of commerce continued to be sources of great wealth. After Constantinople became the capital of the East, a new road system grew up connecting the provinces with the capital. Sardis then lay rather apart from the great lines of communication and lost some of its importance.[citation needed]

During the cataclysmic 7th-century Byzantine–Sasanian War, Sardis was in 615 one of the cities sacked in the invasion of Asia Minor by the Persian Shahin. Though the Byzantines eventually won the war, the damage to Sardis was never fully repaired.[citation needed]

Sardis retained its titular supremacy and continued to be the seat of the metropolitan bishop of the province of Lydia, formed in 295 AD. It was enumerated as third, after Ephesus and Smyrna, in the list of cities of the Thracesion thema given by Constantine Porphyrogenitus in the 10th century. However, over the next four centuries it was in the shadow of the provinces of Magnesia-upon-Sipylum and Philadelphia, which retained their importance in the region.[citation needed]

Later history

[edit]Sardis began to decline in the 600s AD.[1](p1123) It remained part of the Byzantine Empire until 1078 AD, by the Seljuk Turks. It was reconquered in 1097 by the Byzantine general John Doukas and came under the rule of the Byzantine Empire of Nicaea when Constantinople was taken by the Venetians and crusaders in 1204. However, once the Byzantines retook Constantinople in 1261, Sardis and surrounding areas fell under the control of Ghazw emirs. The Cayster valleys and a fort on the citadel of Sardis were handed over to them by treaty in 1306. The city continued its decline until its capture and probable destruction by the Turco-Mongol warlord Timur in 1402.[citation needed]

By the 1700s, only two small hamlets existed at the site. In the 20th century, a new town was built.[1](pp1123–1124)

Foundation stories

[edit]

Herodotus recounts a legend that the city was founded by the sons of Heracles, the Heracleidae. According to Herodotus, the Heraclides ruled for five hundred and five years beginning with Agron, 1220 BC, and ending with Candaules, 716 BC. They were followed by the Mermnades, which began with Gyges, 716 BC, and ended with Croesus, 546 BC.[10]

The name "Sardis" appears first in the work of the Archaic era poet Sappho. Strabo claims that the city's original name was "Hyde".[1](pp1115–1116)

Geography

[edit]Sardis was situated in the middle of Hermus River Valley, about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) south of the river. Its citadel was built on Mount Tmolus, a steep and lofty spur, while a lower town extended to the area of the Pactolus stream.

Today, the site is located by the present day village of Sart, near Salihli in the Manisa province of Turkey, close to the Ankara - İzmir highway (approximately 72 kilometres (45 mi) from İzmir). The site is open to visitors year-round, where notable remains include the bath-gymnasium complex, synagogue and Byzantine shops is open to visitors year-round.

Excavation history

[edit]

By the 19th century, Sardis was in ruins, with mainly visible remains mostly from the Roman period. Early excavators included the British explorer George Dennis, who uncovered an enormous marble head of Faustina the Elder. Found in the precinct of the Temple of Artemis, it probably formed part of a pair of colossal statues devoted to the Imperial couple. The 1.76 metre high head is now kept at the British Museum.[11]

The first large-scale archaeological expedition in Sardis was directed by a Princeton University team led by Howard Crosby Butler between years 1910–1914, unearthing a temple to Artemis, and more than a thousand Lydian tombs. The excavation campaign was halted by World War I, followed by the Turkish War of Independence, though it briefly resumed in 1922. Some surviving artifacts from the Butler excavation were added to the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

A new expedition known as the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis was founded in 1958 by G.M.A. Hanfmann, professor in the Department of Fine Arts at Harvard University, and by Henry Detweiler, dean of the Architecture School at Cornell University. Hanfmann excavated widely in the city and the region, excavating and restoring the major Roman bath-gymnasium complex, the synagogue, late Roman houses and shops, a Lydian industrial area for processing electrum into pure gold and silver, Lydian occupation areas, and tumulus tombs at Bintepe.[12]

During the 1960s, the acknowledgment of the local significance of the Jewish community in Sardis received notable confirmation through the identification of a substantial assembly hall in the northwestern part of the city, now known as the Sardis Synagogue. This site, adorned with inscriptions, menorahs, and various artifacts, establishes its function as a synagogue from the 4th to the 6th century. Excavations in adjacent residential and commercial areas have also uncovered additional evidence of Jewish life.[13]

From 1976 until 2007, excavation continued under Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr., professor in the Department of Classics at the University of California, Berkeley.[14] Since 2008, the excavation has been under the directorship of Nicholas Cahill, professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[15]

Some of the important finds from the site of Sardis are housed in the Archaeological Museum of Manisa, including Late Roman mosaics and sculpture, a helmet from the mid-6th century BC, and pottery from various periods.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Greenewalt, Crawford (2011). "Sardis: A First Millenium B.C.E. Capital In Western Anatolia". In Steadman, Sharon; McMahon, Gregory (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0052.

- ^ a b c Roosevelt, Christopher (2010). "Lydia before the Lydians". The Lydians and Their World.

- ^ Briant, Pierre (January 2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 36. ISBN 9781575061207.

- ^ a b c d e Cahill, Nicholas (2010). "The Persian Sack of Sardis". The Lydians and Their World.

- ^ a b c d Greenwalt, Crawford (2010). "Introduction". The Lydians and Their World.

- ^ a b c Cahill, Nicholas (2010). "The City of Sardis". The Lydians and Their World.

- ^ Meriçboyu, Yıldız Akyay (2010). "Lydian Jewelry". The Lydians and Their World.

- ^ Tacitus, The Annals 2.47

- ^ Revelation 3:1–6

- ^ Cockayne, O. (1844). "On the Lydian Dynasty which preceded the Mermnadæ". Proceedings of the Philological Society. 1 (24): 274–276. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1844.tb00026.x.

- ^ "Research collection online". British Museum.

- ^ Hanfmann, George M. A. (1983). Sardis from Prehistoric to Roman Times: Results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, 1958-1975. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-78925-8.[page needed]

- ^ Rautman, Marcus (2015). "A menorah plaque from the center of Sardis". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 28: 431–438. doi:10.1017/S1047759415002573. ISSN 1047-7594.

- ^ Cahill, Nicholas; Ramage, Andrew, eds. (2008). Love for Lydia: A Sardis Anniversary Volume Presented to Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03195-1.[page needed]

- ^ "Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, Harvard Art Museums". Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Elderkin, George Wicker (1940). "The Name of Sardis". Classical Philology. 35 (1): 54–56. doi:10.1086/362320. JSTOR 264594. S2CID 162247979.

- Hanfmann, George M. A. (1961). "Excavations at Sardis". Scientific American. 204 (6): 124–138. Bibcode:1961SciAm.204f.124H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0661-124. JSTOR 24937494.

- George M. A. Hanfmann (1964), Guide to Sardis (in Turkish and English), Wikidata Q105988871

- Hanfmann, George M. A.; Detweiler, A. H. (1966). "Sardis Through the Ages". Archaeology. 19 (2): 90–97. JSTOR 41670460.

- Hanfmann, George M. A. (November 1973). "Archeological Explorations of Sardis". Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 27 (2): 13–26. doi:10.2307/3823622. JSTOR 3823622.

- Hanfmann, George M. A. (1983). Sardis from Prehistoric to Roman Times: Results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, 1958-1975. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-78925-8.

- Hanfmann, George M. A. (1987). "The Sacrilege Inscription: The Ethnic, Linguistic, Social and Religious Situation at Sardis at the End of the Persian Era". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 1: 1–8. JSTOR 24048256.

- Greenewalt, Crawford H.; Rautman, Marcus L.; Cahill, Nicholas D. (1988). "The Sardis Campaign of 1985". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. Supplementary Studies (25): 55–92. JSTOR 20066668.

- Ramage, Andrew (1994). "Early Iron Age Sardis and its neighbours". In Çilingiroğlu, A.; French, D.H. (eds.). Anatolian Iron Ages 3: The Proceedings of the Third Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Held at Van, 6-12 August 1990. Vol. 16. British Institute at Ankara. pp. 163–172. ISBN 978-1-898249-05-4. JSTOR 10.18866/j.ctt1pc5gxc.26.

- Ramage, Nancy H. (1994). "Pactolus Cliff: An Iron Age Site at Sardis and Its Pottery". In Çilingiroğlu, A.; French, D.H. (eds.). Anatolian Iron Ages 3: The Proceedings of the Third Anatolian Iron Ages Colloquium Held at Van, 6-12 August 1990. Vol. 16. British Institute at Ankara. pp. 173–184. ISBN 978-1-898249-05-4. JSTOR 10.18866/j.ctt1pc5gxc.27.

- Greenwalt, Crawford H. (1995). "Sardis in the Age of Xenophon". Pallas. 43 (1): 125–145. doi:10.3406/palla.1995.1367.

- Gadbery, Laura M. (1996). "Archaeological Exploration of Sardis". Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin. 4 (3): 49–53. JSTOR 4301536.

- Mitten, David Gordon (1996). "Lydian Sardis and the Region of Colchis : Three Aspects". Collection de l'Institut des Sciences et Techniques de l'Antiquité. 613 (1): 129–140. ProQuest 305180080.

- Greenewalt, Crawford H.; Rautman, Marcus L. (1998). "The Sardis Campaigns of 1994 and 1995". American Journal of Archaeology. 102 (3): 469–505. doi:10.2307/506398. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 506398. S2CID 191368428.

- Cahill, Nicholas; Ramage, Andrew, eds. (2008). Love for Lydia: A Sardis Anniversary Volume Presented to Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03195-1.

- Payne, Annick; Wintjes, Jorit (2016). "Sardis and the Archaeology of Lydia". Lords of Asia Minor: An Introduction to the Lydians. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 47–62. ISBN 978-3-447-10568-2. JSTOR j.ctvc5pfx2.7.

- Berlin, Andrea M.; Kosmin, Paul J., eds. (2019). Spear-Won Land: Sardis from the King's Peace to the Peace of Apamea. University of Wisconsin Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvj7wnr9. ISBN 978-0-299-32130-7. JSTOR j.ctvj7wnr9. S2CID 241097314.

External links

[edit]- The Archaeological Exploration of Sardis

- The Search for Sardis, history of the archaeological excavations in Sardis, in the Harvard Magazine

- Sardis, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Sardis Turkey, a comprehensive photographic tour of the site

- The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites - Sardis

- Livius.org: Sardes - pictures

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Geographic | |