| Part of a series on |

| Science |

|---|

| This is a subseries on philosophy. In order to explore related topics, please visit navigation. |

Scientific literature encompasses a vast body of academic papers that spans various disciplines within the natural and social sciences. It primarily consists of academic papers that present original empirical research and theoretical contributions. These papers serve as essential sources of knowledge and are commonly referred to simply as “the literature” within specific research fields.

The process of academic publishing involves disseminating research findings to a wider audience. Researchers submit their work to reputable journals or conferences, where it undergoes rigorous evaluation by experts in the field. This evaluation, known as peer review, ensures the quality, validity, and reliability of the research before it becomes part of the scientific literature. Peer-reviewed publications contribute significantly to advancing our understanding of the world and shaping future research endeavors.

Original scientific research first published in scientific journals constitutes primary literature. Patents and technical reports, which cover minor research results and engineering and design efforts, including computer software, are also classified as primary literature.

Secondary sources comprise review articles that summarize the results of published studies to underscore progress and new research directions, as well as books that tackle extensive projects or comprehensive arguments, including article compilations.

Tertiary sources encompass encyclopedias and similar works designed for widespread public consumption.

Scientific literature can include the following kinds of publications:[1]

Literature may also be published in areas considered to be "grey", as they are published outside of traditional channels.[1] This material is customarily not indexed by major databases and can include manuals, theses and dissertations, or newsletters and bulletins.[1]

The significance of different types of the scientific publications can vary between disciplines and change over time.[citation needed] According to James G. Speight and Russell Foote, peer-reviewed journals are the most prominent and prestigious form of publication.[2] University presses are more prestigious than commercial press publication.[3] The status of working papers and conference proceedings depends on the discipline; they are typically more important in the applied sciences. The value of publication as a preprint or scientific report on the web has in the past been low, but in some subjects, such as mathematics or high energy physics, it is now an accepted alternative.[citation needed]

Scientific papers have been categorised into ten types. Eight of these carry specific objectives, while the other two can vary depending on the style and the intended goal.[4]

Papers that carry specific objectives are:[4]

The following two categories are variable, including for example historical articles and speeches:[4]

|

For broader class of these articles, see Scholarly article. |

|

See also: Types of scientific journal articles |

The actual day-to-day records of scientific information are kept in research notebooks or logbooks. These are usually kept indefinitely as the basic evidence of the work, and are often kept in duplicate, signed, notarized, and archived. The purpose is to preserve the evidence for scientific priority, and in particular for priority for obtaining patents. They have also been used in scientific disputes. Since the availability of computers, the notebooks in some data-intensive fields have been kept as database records, and appropriate software is commercially available.[5]

The work on a project is typically published as one or more technical reports, or articles. In some fields both are used, with preliminary reports, working papers, or preprints followed by a formal article. Articles are usually prepared at the end of a project, or at the end of components of a particularly large one. In preparing such an article vigorous rules for scientific writing have to be followed.

|

See also: Impact factor and Copy editing |

Often, career advancement depends upon publishing in high-impact journals, which, especially in hard and applied sciences, are usually published in English.[6] Consequently, scientists with poor English writing skills are at a disadvantage when trying to publish in these journals, regardless of the quality of the scientific study itself.[7] Yet many[which?] international universities require publication in these high-impact journals by both their students and faculty. One way that some international authors are beginning to overcome this problem is by contracting with freelance copy editors who are native speakers of English and specialize in ESL (English as a second language) editing to polish their manuscripts' English to a level that high-impact journals will accept.[citation needed]

|

Main article: IMRAD |

Although the content of an article is more important than the format, it is customary for scientific articles to follow a standard structure, which varies only slightly in different subjects. Although the IMRAD structure emphasizes the organization of content, and in scientific journal articles, each section (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) has unique conventions for scientific writing style.[8]

The following are key guidelines for formatting, although each journal etc will to some extent have its own house style:

|

Main article: Scholarly peer review |

Increasing reliance on digital abstracting services and academic search engines means that the de facto acceptance in the academic discourse is predicted by the inclusion in such selective sources. Commercial providers of proprietary data include Chemical Abstracts Service, Web of Science and Scopus, while open data (and often open source, non-profit and library-led) services include DOAB, DOAJ and (for open access works) Unpaywall (based on CrossRef and Microsoft Academic records enriched with OAI-PMH data from open archives).[12]

The transfer of copyright from author to publisher, used by some journals, can be controversial because many authors want to propagate their ideas more widely and re-use their material elsewhere without the need for permission. Usually an author or authors circumvent that problem by rewriting an article and using other pictures. Some publishers may also want publicity for their journal so will approve facsimile reproduction unconditionally; other publishers are more resistant. [citation needed]

In terms of research publications, a number of key issues include and are not restricted to:[13]

|

See also: Scientific writing § History |

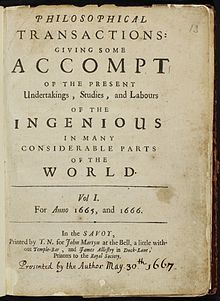

The first recorded editorial pre-publication peer-review occurred in 1665 by the founding editor of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Henry Oldenburg.[18][19]

Technical and scientific books were a specialty of David Van Nostrand, and his Engineering Magazine re-published contemporary scientific articles.