William Osler | |

|---|---|

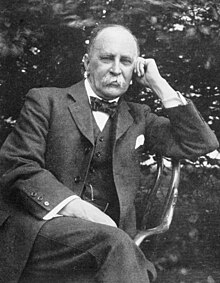

Photograph of Osler, c. 1912 | |

| Born | July 12, 1849 |

| Died | December 29, 1919 (aged 70) Oxford, England |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Alma mater | McGill University (MDCM) |

| Known for | co-founding physician of Johns Hopkins Hospital |

| Spouse | Grace Revere Osler |

| Children | 2 sons |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physician, pathologist, internist, educator, bibliophile, author and historian |

| Institutions | |

| Signature | |

| |

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, FRS FRCP (/ˈɒzlər/; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the "Big Four" founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first residency program for specialty training of physicians, and he was the first[clarification needed] to bring medical students out of the lecture hall for bedside clinical training.[1][better source needed] He has frequently been described as the Father of Modern Medicine and one of the "greatest diagnosticians ever to wield a stethoscope".[2][3] In addition to being a physician he was a bibliophile, historian, author, and renowned practical joker. He was passionate about medical libraries and medical history, having founded the History of Medicine Society (formally "section"), at the Royal Society of Medicine, London.[4] He was also instrumental in founding the Medical Library Association of Great Britain and Ireland, and the (North American) Association of Medical Librarians (later the Medical Library Association) along with three other people, including Margaret Charlton, the medical librarian of his alma mater, McGill University. He left his own large history of medicine library to McGill, where it became the Osler Library.

William Osler's great-grandfather, Edward Osler, was variously described as either a merchant seaman or a pirate.[5] One of William's uncles, Edward Osler (1798–1863), a medical officer in the Royal Navy, wrote the Life of Lord Exmouth and the poem The Voyage.[6]

William Osler's father, the Reverend Featherstone Lake Osler (1805–1895), the son of a shipowner at Falmouth, Cornwall, was a former lieutenant in the Royal Navy who served on HMS Victory. In 1831, Featherstone Osler was invited to serve on HMS Beagle as the science officer for Charles Darwin's historic voyage to the Galápagos Islands, but he turned it down because his father was dying. In 1833, Featherstone Osler announced that he wanted to become a minister of the Church of England.[7]

As a teenager, Featherstone Osler was aboard HMS Sappho when it was nearly destroyed by Atlantic storms and remained adrift for weeks. Serving in the Navy, he was shipwrecked off Barbados. In 1837, Featherstone Osler retired from the Navy and emigrated to Canada, becoming a "saddle-bag minister" in rural Upper Canada. When Featherstone and his bride, Ellen Free Picton, arrived in Canada, they were nearly shipwrecked again on Egg Island in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Their children included William, Britton Bath Osler and Sir Edmund Boyd Osler.

William Osler was born in Bond Head, Canada West (Ontario), on July 12, 1849, and raised after 1857 in Dundas, Ontario. He was named William after William of Orange, who won the Battle of the Boyne on July 12, 1690. Osler's mother, who was very religious, prayed that he would become a priest.[8] Osler was educated at Trinity College School (then located in Weston, Ontario).

In 1867, Osler announced that he would follow his father's footsteps into the ministry and entered Trinity College of the University of Toronto, in the autumn. However, he became increasingly interested in medical science under the influence of James Bovell and the Rev. William Arthur Johnson, encouraging him to switch his career.[9][10][11]

In 1868, Osler enrolled in the Toronto School of Medicine,[12] a privately owned institution that was not part of the Medical Faculty of the University of Toronto. Osler lived with James Bovell for a time, and through Johnson, he was introduced to the writings of Sir Thomas Browne; his Religio Medici caused a deep impression on him.[13] Osler left the Toronto School of Medicine after being accepted into the MDCM program at the McGill University Faculty of Medicine in Montreal, and he received his medical degree (MDCM) in 1872.

Following post-graduate training under Rudolf Virchow in Germany, Osler returned to the McGill University Faculty of Medicine as a professor in 1874. There he created the first formal journal club, showed interest in comparative pathology, and is considered the first to have taught veterinary pathology in North America as part of a broad understanding of disease pathogenesis. In 1884, he was appointed Chair of Clinical Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and in 1885, was one of the seven founding members of the Association of American Physicians, a society dedicated to "the advancement of scientific and practical medicine." When he left Philadelphia in 1889, his farewell address, "Aequanimitas",[14] was about the imperturbability (calm amid storm) and equanimity (moderated emotion, tolerance) necessary for physicians.[15]

In 1889, he became the first Physician-in-Chief of the new Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. In 1893, Osler was instrumental in creating the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and became one of the school's first professors of medicine. Osler quickly enhanced his reputation as a clinician, humanitarian, and teacher. He presided over the rapidly expanding hospital's first year of operation, when it had 220 beds and 788 patients were seen for a total of over 15,000 days of treatment. Sixteen years later, when Osler left for Oxford, over 4,200 patients were seen for a total of nearly 110,000 days of treatment.[16]

In 1905, he was appointed to the Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford, which he held until his death. He was also a Student (fellow) of Christ Church, Oxford.

In the UK, he initiated the founding in 1907 of the Association of Physicians[17] and was founding Senior Editor of its publication the Quarterly Journal of Medicine until his death.[18]

In 1911, he founded the Postgraduate Medical Association and was its first President.[19] The same year, Osler was named a baronet in the Coronation Honours List for his contributions to the field of medicine.[20]

In January 1919 he was appointed President of the Fellowship of Medicine [21] and was in October appointed founding President of the merged Fellowship of Medicine and Postgraduate Medical Association,[22] which became the Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine.

The largest collection of Osler's letters and papers is at the Osler Library of McGill University in Montreal and a collection is also held at the United States National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland.[23][24]

Perhaps Osler's greatest influence on medicine was to insist that students learn from seeing and talking to patients and the establishment of the medical residency. The latter idea spread across the English-speaking world and remains in place today in most teaching hospitals. Through this system, physicians in training make up much of a teaching hospital's medical staff. The success of his residency system depended, in large part, on its pyramidal structure with many interns, fewer assistant residents and a single chief resident, who originally occupied that position for years. While at Hopkins, Osler established the full-time, sleep-in residency system whereby staff physicians lived in the administration building of the hospital. As established, the residency was open-ended, and long tenure was the rule. Physicians spent as long as seven or eight years as residents, during which time they led a restricted, almost monastic life.

He wrote in an essay "Books and Men" that "He who studies medicine without books sails an uncharted sea, but he who studies medicine without patients does not go to sea at all."[25] His best-known saying was "Listen to your patient, he is telling you the diagnosis", which emphasises the importance of taking a good history.[2]

The contribution to medical education of which he was proudest was his idea of clinical clerkship – having third- and fourth-year students work with patients on the wards. He pioneered the practice of bedside teaching, making rounds with a handful of students, demonstrating what one student referred to as his method of "incomparably thorough physical examination." Soon after arriving in Baltimore, Osler insisted that his medical students attend at bedside early in their training. By their third year they were taking patient histories, performing physicals and doing lab tests examining secretions, blood and excreta.

He reduced the role of didactic lectures and once said he hoped his tombstone would say only, "He brought medical students into the wards for bedside teaching." He also said, "I desire no other epitaph … than the statement that I taught medical students in the wards, as I regard this as by far the most useful and important work I have been called upon to do." Osler fundamentally changed medical teaching in North America, and this influence, helped by a few such as the Dutch internist P. K. Pel, spread to medical schools across the globe.

Osler was a prolific author and a great collector of books and other material relevant to the history of medicine. He willed his library to the Faculty of Medicine of McGill University where it now forms the nucleus of McGill University's Osler Library of the History of Medicine.[26] Osler was a strong supporter of libraries and served on the library committees at most of the universities at which he taught and was a member of the Board of Curators of the Bodleian Library in Oxford. He was instrumental in founding the Medical Library Association in North America, alongside employee and mentee Marcia Croker Noyes,[27] and served as its second president from 1901 to 1904. In Britain he was the first (and only) president of the Medical Library Association of Great Britain and Ireland[28] and also a president of the Bibliographical Society of London (1913).[29]

Osler was a prolific author and public speaker and his public speaking and writing were both done in a clear, lucid style. His most famous work, The Principles and Practice of Medicine quickly became a key text to students and clinicians alike. It continued to be published in many editions until 2001 and was translated into many languages.[30][31] It is notable in part for supporting the use of bloodletting as recently as 1923.[32] Though his own textbook was a major influence in medicine for many years, Osler described Avicenna as the "author of the most famous medical textbook ever written". He noted that Avicenna's Canon of Medicine remained "a medical bible for a longer time than any other work".[33] Osler's essays were important guides to physicians. The title of his most famous essay, "Aequanimitas", espousing the importance of imperturbability, is the motto on the Osler family crest and is used on the Osler housestaff tie and scarf at Hopkins.

Osler said Canada should be a "white man's country" in a 1914 speech given around the time of the Komagata Maru incident involving immigration from India.[34][35] Osler wrote “I hate Latin Americans” in a letter to Henry Vining Ogden.[36][37] Under the pseudonym "Egerton Yorrick Davis", Osler mocked Indigenous people: “Every primitive tribe retains some vile animal habit not yet eliminated in the upward march of the race.” [38] Uncovering this historical context, the journalists David Bruser and Markus Grill and the archivist Nils Seethaler reconstruct the shipment of several indigenous skulls by Osler from Canada to Germany, which were (previously unknown) in the custody of the State Museums of Berlin.[39]

Osler is well known in the field of gerontology for the speech he gave when leaving Hopkins to become the Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford. "The Fixed Period", given on February 22, 1905, included some controversial words about old age. Osler, who had a well-developed humorous side to his character, was in his mid-fifties when he gave the speech and in it he mentioned Anthony Trollope's The Fixed Period (1882), which envisaged a college where men retired at 67 and after being given a year to settle their affairs, would be "peacefully extinguished by chloroform". He claimed that, "the effective, moving, vitalizing work of the world is done between the ages of twenty-five and forty" and it was downhill from then on.[40] Osler's speech was covered by the popular press which headlined their reports with "Osler recommends chloroform at sixty".[41] The concept of mandatory euthanasia for humans after a "fixed period" (often 60 years) became a recurring theme in 20th century science fiction—for example, Isaac Asimov's 1950 novel Pebble in the Sky and Half a Life (Star Trek: The Next Generation). In the 3rd edition of his Textbook, he also coined the description of pneumonia as "the friend of the aged" since it allowed elderly individuals a quick, comparatively painless death: "Taken off by it in an acute, short, not often painful illness, the old man escapes those "cold gradations of decay" so distressing to himself and his friends."[42] Coincidentally, Osler himself died of pneumonia.

An inveterate prankster, he wrote several humorous pieces under the pseudonym "Egerton Yorrick Davis", even fooling the editors of the Philadelphia Medical News into publishing a report on the extremely rare phenomenon of penis captivus, on December 13, 1884.[43] The letter was apparently a response to a report on the phenomenon of vaginismus reported three weeks previously in the Philadelphia Medical News by Osler's colleague Theophilus Parvin.[44] Davis, a prolific writer of letters to medical societies, purported to be a retired U.S. Army surgeon living in Caughnawaga, Quebec (now Kahnawake), author of a fake paper on the obstetrical habits of Native American tribes that was intended as a joke on his rival, Dr. William A. Molson. The piece was never published in Osler's lifetime, nor was it intended to be published; Osler knew the content was outrageous, but he wanted to make a fool of Molson by getting the piece to the brink of publication in the Montreal Medical Journal, of which Molson was the editor. Osler would enhance Davis's myth by signing Davis's name to hotel registers and medical conference attendance lists; Davis was eventually reported drowned in the Lachine Rapids in 1884.[44]

Throughout his life, Osler was a great admirer of the 17th century physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne.

He died at the age of 70, on December 29, 1919, in Oxford, during the Spanish influenza epidemic, most likely of complications from undiagnosed bronchiectasis.[45] His wife, Grace, lived another nine years but succumbed to a series of strokes. Sir William and Lady Osler's ashes now rest in a niche in the Osler Library at McGill University. They had two sons, one of whom died shortly after birth. The other, Edward Revere Osler, was mortally wounded in combat in World War I at the age of 21, during the 3rd battle of Ypres (also known as the battle of Passchendaele). At the time of his death in August 1917, he was a second lieutenant in the (British) Royal Field Artillery;[46] Lt. Osler's grave is in the Dozinghem Military Cemetery in West Flanders, Belgium.[47] According to one biographer, Osler was emotionally crushed by the loss; he was particularly anguished by the fact that his influence had been used to procure a military commission for his son, who had mediocre eyesight.[48] Lady Osler (Grace Revere) was born in Boston in 1854; her paternal great-grandfather was Paul Revere.[49] In 1876, she married Samuel W. Gross, chairman of surgery at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia and son of Dr. Samuel D. Gross. Gross died in 1889 and in 1892 she married William Osler who was then professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

Osler was a founding donor of the American Anthropometric Society, a group of academics who pledged to donate their brains for scientific study.[50] His brain was donated to the American Anthropometric Society after his death and is currently stored at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia. A study of his brain, conducted in 1927, concluded that there were differences between the brains of the highly intelligent and normal brains.[51] In April 1987 it was taken to the Mütter Museum, on 22nd Street near Chestnut in Philadelphia where it was displayed during the annual meeting of the American Osler Society.[52][53] He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society in 1885.[54]

In 1925, a biography of William Osler was written by Harvey Cushing,[55] who received the 1926 Pulitzer Prize for the work. A later biography by Michael Bliss was published in 1999.[48] In 1994 Osler was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame.[56]

Osler lent his name to a number of diseases, signs and symptoms, as well as to a number of buildings that have been named for him.[57][58]