Vowels

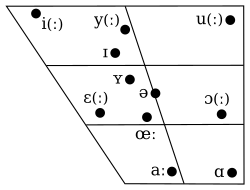

Dutch has an extensive vowel inventory consisting of thirteen plain vowels and at least three diphthongs. Vowels can be grouped as front unrounded, front rounded, central and back. They are also traditionally distinguished by length or tenseness. The vowels /eː, øː, oː/ are included in one of the diphthong charts further below because Northern Standard Dutch realizes them as diphthongs, but they behave phonologically like the other long monophthongs.

Monophthongs

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Dutch vowels can be classified as lax and tense,[31] checked and free[32] or short and long.[33] Phonetically however, the close vowels /i, y, u/ are as short as the phonological lax/short vowels unless they occur before /r/.[34][35]

- Phonologically, /ɪ, ʏ, ʊ/ can be classified as either close or close-mid. Carlos Gussenhoven classifies them as the former,[36] whereas Geert Booij says that they are the latter and classifies /ɛ, ɔ/ and the non-native mid vowels as open-mid.[24]

- /ʏ/ has been traditionally transcribed with ⟨œ⟩, but modern sources tend to use ⟨ʏ⟩ or ⟨ɵ⟩ instead.[37][38] Beverley Collins and Inger Mees write this vowel with ⟨ʉ⟩.[39]

- The phonemic status of /ʊ/ is not clear. Phonetically, a vowel of the [ʊ̞ ~ ɔ̽][40] type appears before nasals as an allophone of /ɔ/, e.g. in jong [jʊŋ] ('young'). This vowel can also be found in certain other words, such as op [ʊp] ('on'), which can form a near-minimal pair with mop [mɔp] ('joke'). This, however, is subject to both individual and geographical variation.[41][42]

- Many speakers feel that /ə/ and /ʏ/ belong to the same phoneme, with [ə] being its unstressed variant. This is reflected in spelling errors produced by Dutch children, for example ⟨binnu⟩ for binnen [ˈbɪnə(n)] ('inside'). Adding to this, the two vowels have different phonological distribution; for example, /ə/ can occur word-finally, while /ʏ/ (along with other lax vowels) cannot. In addition, the word-final allophone of /ə/ is a close-mid front vowel with some rounding [ø̜], a sound that is similar to /ʏ/.[24][43]

- The native tense vowels /eː, øː, oː, aː/ are long [eː, øː, oː, aː] in stressed syllables and short [e, ø, o, a] elsewhere. The non-native oral vowels appear only in stressed syllables and thus are always long.[44]

- The native /eː, øː, oː, aː/ as well as the non-native nasal /ɛ̃ː, œ̃ː, ɔ̃ː, ɑ̃ː/ are sometimes transcribed without the length marks, as ⟨e, ø, o, a, ɛ̃, œ̃, ɔ̃, ɑ̃⟩.[45]

- The non-native /iː, yː, uː, ɛː, œː, ɔː/ occur only in stressed syllables. In unstressed syllables, they are replaced by the closest native vowel. For instance, verbs corresponding to the nouns analyse ('analysis'), centrifuge ('spinner'), and zone ('zone') are analyseren ('to analyze'), centrifugeren ('to spin-dry'), and zoneren /zoːˈneːrən/ ('to divide into zones').[46]

- /œː/ is extremely rare, and the only words of any frequency in which it occurs are oeuvre , manoeuvre and freule. In the more common words, /ɛː/ tends to be replaced with the native /ɛ/, whereas /ɔː/ can be replaced by either /ɔ/ or /oː/ (Belgians typically select the latter).[28]

- The non-native nasal vowels /ɛ̃ː, œ̃ː, ɔ̃ː, ɑ̃ː/ occur only in loanwords from French.[3][27][47] /ɛ̃ː, ɔ̃ː, ɑ̃ː/ are often nativized as /ɛn, ɔn, ɑn/, /ɛŋ, ɔŋ, ɑŋ/ or /ɛm, ɔm, ɑm/, depending on the place of articulation of the following consonant. For instance, restaurant /rɛstoːˈrɑ̃ː/ ('restaurant') and pardon /pɑrˈdɔ̃ː/ ('excuse me') are often nativized as and , respectively.[47] /œ̃ː/ is extremely rare, just like its oral counterpart[48] and the only word of any frequency in which it occurs is parfum /pɑrˈfœ̃ː/ ('perfume'), often nativized as /pɑrˈfʏm/ or .

- The non-native /ɑː/ is listed only by some sources.[49] It occurs in words such as cast ('cast').[27][50]

The following sections describe the phonetic quality of Dutch monophthongs in detail.

Close vowels

- /ɪ/ is close to the canonical value of the IPA symbol ⟨ɪ⟩.[51][39] The Standard Belgian realization has also been described as close-mid [ɪ̞].[52] In regional Standard Dutch, the realization may be different: for example, in Antwerp it is closer, more like [i], whereas in places like Dordrecht, Nijmegen, West and East Flanders the vowel is typically more open than the Standard Dutch counterpart, more like [ë]. Affected speakers of Northern Standard Dutch may also use this vowel.[53][54]

- /i, iː/ are close front [i, iː], close to cardinal [i].[35][51][52]

- The majority of sources consider /ʏ/ to be close-mid central [ɵ],[52][55][56] yet Beverley Collins and Inger Mees consider it to be close-mid front [ʏ̞].[39] The study conducted by Vincent van Heuven and Roos Genet has shown that native speakers consider the canonical IPA value of the symbol ⟨ɵ⟩ to be the most similar to the Dutch sound, much more similar than the canonical values of ⟨ʏ⟩ and ⟨œ⟩ (the sound represented by ⟨ʉ⟩ was not a part of the study).[55] In regional Standard Dutch /ʏ/ may be raised to near-close [ɵ̝], for example in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague. In Antwerp, the vowel may be as high as /y/ and the two vowels may differ in nothing but length. A more open vowel of the [ɵ̞]-type is found in southern accents (e.g. in Bruges) and in affected Northern Standard Dutch.[53][54]

- /y, yː/ have been variously described as close front [y, yː],[52][57] near-close front [y˕, y˕ː][35] and, in Northern Standard Dutch, near-close central [ʉ̞, ʉ̞ː].[51]

- /u, uː/ are close back [u, uː] in Northern Standard Dutch and close near-back [u̟, u̟ː] in Belgian Standard Dutch and some varieties of regional Standard Dutch spoken in Antwerp and Flemish Brabant.[51][52][58]

Word-final /i, y, u/ are raised and end in a voiceless vowel: [ii̥, yẙ, uu̥]. The voiceless vowel in the first sequence may sound almost like a palatal fricative [ç].[35]

/i, y, u/ are frequently longer in Belgian Standard Dutch and most Belgian accents than in Northern Standard Dutch in which the length of these vowels is identical to that of lax vowels.[35]

Regardless of the exact accent, /i, y, u/ are mandatorily lengthened to [iː, yː, uː] before /r/ in the same word.[27][35][51] In Northern Standard Dutch and in Randstad, these are laxed to [i̽ː, y˕ː, u̽ː] and often have a schwa-like off-glide ([i̽ə, y˕ə, u̽ə]). This means that before /r/, /i, y, u/ are less strongly differentiated from /eː, øː, oː/ in Northern Standard Dutch and Randstad than is usually the case in other regional varieties of Standard Dutch and in Belgian Standard Dutch.[59] There is one exception to the lengthening rule: when /r/ is followed by a consonant different than /t/ and /s/, /i, y, u/ remain short. Examples of that are words such as wierp [ʋirp], Duisburg [ˈdyzbur(ə)k] (alternatively: [ˈdœyzbʏr(ə)x], with a lax vowel) and stierf [stirf]. The rule is also suppressed syllable-finally in certain compounds; compare roux-room [ˈruroːm] with roerroom [ˈruːr(r)oːm] and Ruhr-Ohm [ˈruːroːm].[27][60]

Mid vowels

- /ɛ, ɛː/ are open-mid front [ɛ, ɛː].[51][61] According to Jo Verhoeven, the Belgian Standard Dutch variants are somewhat raised.[52] Before /n/ and the velarized or pharyngealized allophone of /l/, /ɛ/ is typically lowered to [æ]. In some regional Standard Dutch (e.g. in Dordrecht, Ghent, Bruges and more generally in Zeeland, North Brabant and Limburg), this lowering is generalized to most or even all contexts. Conversely, some regional Standard Dutch varieties (e.g. much of Randstad Dutch, especially the Amsterdam dialect as well as the accent of Antwerp) realize the main allophone of /ɛ/ as higher and more central than open-mid front ([ɛ̝̈]).[62]

- /œː/ is open-mid front [œː].[51][63]

- /ə/ has two allophones, with the main one being mid central unrounded [ə]. The allophone used in word-final positions resembles the main allophone of /ʏ/ as it is closer, more front and more rounded ([ø̜]).[43][51]

- /ɔ/ is open-mid back rounded [ɔ].[51][52] Collins and Mees (2003) describe it as "very tense", with pharyngealization and strong lip-rounding.[35] There is considerable regional and individual variation in the height of /ɔ/, with allophones being as close as [ʊ] in certain words.[64][65] The closed allophones are especially common in the Randstad area.[35] /ɔː/ is close to /ɔ/ in terms of height and backness.

/ɛ, ɔ/ are typically somewhat lengthened and centralized before /r/ in Northern Standard Dutch and Randstad, usually with a slight schwa-like offglide: [ɛ̈ə̆, ɔ̈ə̆]. In addition, /ɔ/ in this position is somewhat less rounded ([ɔ̜̈ə̆]) than the main allophone of /ɔ/.[66]

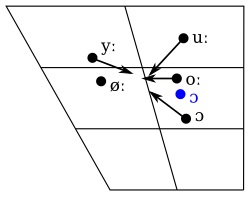

The free vowels /eː, øː, oː/ are realized as monophthongs [eː, øː, oː] in Belgian Standard Dutch (Jo Verhoeven describes the Belgian Standard Dutch realization of /øː/ as mid-central [ɵ̞ː]) and in many regional accents. In Northern Standard Dutch, narrow closing diphthongs [eɪ, øʏ, oʊ] are used. The starting point of [oʊ] is centralized back ([ö]), and the starting point of [eɪ] has been described as front [e] by Collins and Mees and as centralized front [ë] by Gussenhoven. The monophthongal counterparts of [eɪ, oʊ] are peripheral; the former is almost as front as cardinal [eː], whereas the latter is almost as back as cardinal [oː].[51][52][67] Many speakers of Randstad Dutch as well as younger speakers of Northern Standard Dutch realize /eː, øː, oː/ as rather wide diphthongs of the [ɛɪ, œʏ, ɔʊ] type, which may be mistaken for the phonemic diphthongs /ɛi, œy, ɔu/ by speakers of other accents.[68][69] The use of [ɛɪ, œʏ, ɔʊ] for /eː, øː, oː/ goes hand in hand with the lowering the first elements of /ɛi, œy, ɔu/ to [aɪ, aʏ, aʊ], a phenomenon termed Polder Dutch. Therefore, the phonemic contrast between /eː, øː, oː/ and /ɛi, œy, ɔu/ is still strongly maintained, but its phonetic realization is very different from what one can typically hear in traditional Northern Standard Dutch.[70] In Rotterdam and The Hague, the starting point of [oʊ] can be fronted to [ə] instead of being lowered to [ɔ].[71]

In Northern Standard Dutch and in Randstad, /eː, øː, oː/ lose their closing glides and are raised and slightly centralized to [ɪː, ʏː, ʊː] (often with a schwa-like off-glide [ɪə, ʏə, ʊə]) before /r/ in the same word. The first two allophones strongly resemble the lax monophthongs /ɪ, ʏ/. Dutch children frequently misspell the word weer ('again') as wir. These sounds may also occur in regional varieties of Standard Dutch and in Belgian Standard Dutch, but they are more typically the same as the main allophones of /eː, øː, oː/ (that is, [eː, øː, oː]). An exception to the centralizing rule are syllable-final /eː, øː, oː/ in compounds such as zeereis ('sea voyage'), milieuramp ('environmental disaster') and bureauredactrice [byˈroʊredɑkˌtrisə] ('desk editor (f.)').[72][73]

In Northern Standard Dutch, /eː, øː, oː/ are mid-centralized before the pharyngealized allophone of /l/.[74]

Several non-standard dialects have retained the distinction between the so-called "sharp-long" and "soft-long" e and o, a distinction that dates back to early Middle Dutch. The sharp-long varieties originate from the Old Dutch long ē and ō (Proto-Germanic ai and au), while the soft-long varieties arose from short i/e and u/o that were lengthened in open syllables in early Middle Dutch. The distinction is not considered to be a part of Standard Dutch and is not recognized in educational materials, but it is still present in many local varieties, such as Antwerpian, Limburgish, West Flemish and Zeelandic. In these varieties, the sharp-long vowels are often opening diphthongs such as [ɪə, ʊə], while the soft-long vowels are either plain monophthongs [eː, oː] or slightly closing [eɪ, oʊ].

Open vowels

In Northern Standard Dutch and some other accents, /ɑ, aː/ are realized so that the former is a back vowel [ɑ], whereas the latter is central [äː] or front [aː]. In Belgian Standard Dutch /aː/ is also central or front, but /ɑ/ may be central [ä] instead of back [ɑ], so it may have the same backness as /aː/.[51][75][52]

Other accents may have different realizations:

- Many accents (Amsterdam, Utrecht, Antwerp) realize this pair with 'inverted' backness, so that /ɑ/ is central [ä] (or, in the case of Utrecht, even front [a]), whereas /aː/ is closer to cardinal [ɑː].[76]

- Outside the Randstad, fronting of /ɑ/ to central [ä] is very common. On the other hand, in Rotterdam and Leiden, the short /ɑ/ sounds even darker than the Standard Northern realization, being realized as a fully back and raised open vowel, unrounded [ɑ̝] or rounded [ɒ̝].[35]

- In Groningen, /aː/ tends to be particularly front, similar to the quality of the cardinal vowel [aː], whereas in The Hague and in the affected Standard Northern accent, /aː/ may be raised and fronted to [æː], particularly before /r/.[77]

Before /r/, /ɑ/ is typically a slight centering diphthong with a centralized first element ([ɐə̆]) in Northern Standard Dutch and in Randstad.[66]

Diphthongs

Dutch also has several diphthongs, but only three of them are unquestionably phonemic. All three of them end in a non-syllabic close vowel [i̯, y̑, u̯] (henceforth written [i, y, u] for simplicity), but they may begin with a variety of other vowels.[51][78][79]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- /ɔu/ has been variously transcribed with ⟨ɔu⟩,[80] ⟨ɑu⟩,[81] and ⟨ʌu⟩.[82]

- The starting points of /ɛi, œy, ɔu/ tend to be closer ([ɛɪ, œ̈ʏ, ɔ̈ʊ]) in Belgian Standard Dutch than in Northern Standard Dutch ([ɛ̞ɪ, œ̞̈ʏ, ʌ̞̈ʊ]). In addition, the Belgian Standard Dutch realization of /ɔu/ tends to be fully rounded, unlike the typical Northern Standard Dutch realization of the vowel. However, Jo Verhoeven reports rather open starting points of the Belgian Standard Dutch variants of /œy, ɔu/ ([œ̞̈ʏ, ɔ̞̈ʊ]) and so the main difference between Belgian and Northern Standard Dutch in this respect may only be in the rounding of the first element of /ɔu/, but the fully rounded variant of /ɔu/ is also used by some Netherlandic speakers, particularly of the older generation. It is also used in most of Belgium, in line with the Belgian Standard Dutch realization.[51][52][83]

- In conservative Northern Standard Dutch, the starting points of /ɛi, œy, ɔu/ are open-mid and rounded in the case of the last two vowels: [ɛɪ, œʏ, ɔʊ].[70]

- The backness of the starting point of the Belgian Standard Dutch realization of /ɛi/ has been variously described as front [ɛɪ][68] and centralized front [ɛ̈ɪ].[52]

- In Polder Dutch, which is spoken in some areas of the Netherlands (especially Randstad and its surroundings), the starting points of /ɛi, œy, ɔu/ are further lowered to [aɪ, aʏ, aʊ]. This is typically accompanied by the lowering of the starting points of /eː, øː, oː/ to [ɛɪ, œʏ, ɔʊ]. These realizations have existed in Hollandic dialects since the 16th century and are now are becoming standard in the Netherlands. They are an example of a chain shift similar to the Great Vowel Shift in English. According to Jan Stroop, the fully lowered variant of /ɛi/ is the same as the phonetic diphthong [aːi], making bij 'at' and baai 'bay' perfect homophones.[70][84]

- The rounding of the starting point of the Northern Standard Dutch realization of /œy/ has been variously described as slight [œ̜ʏ][85] and non-existent [ɐ̜ʏ].[56] The unrounded variant has also been reported to occur in many other accents, such as Leiden, Rotterdam and in some Belgian speakers.[84]

- Phonetically, the endpoints of the native diphthongs are lower and more central than cardinal [i, y, u], i.e. more like [ɪ, ʏ, ʊ] or even [e, ø, o] (however, Jo Verhoven reports a rather close ([ï]) endpoints of the Belgian Standard Dutch variant of /ɛi/, so this might be somewhat variable). In Belgian Standard Dutch, the endpoints are shorter than in Northern Standard Dutch, but in both varieties the glide is an essential part of the articulation. Furthermore, in Northern Standard Dutch there is no appreciable difference between the endpoints of /ɛi, œy, ɔu/ and the phonetic diphthongs [eɪ, øʏ, oʊ], with both sets ending in vowels close to [ɪ, ʏ, ʊ].[51][52][79]

- In some regional varieties of Standard Dutch (Southern, regional Belgian), the endpoints of /ɛi, œy, ɔu/ are even lower than in Standard Dutch: [ɛe̞, œø̞, ɔo̞ ~ ʌo̞], and in the traditional dialect of The Hague they are pure monophthongs [ɛː, œː, ɑː]. Broad Amsterdam speakers can also monophthongize /ɛi/, but to [aː]. It typically does not merge with /aː/ as that vowel has a rather back ([ɑː]) realization in Amsterdam.[86]

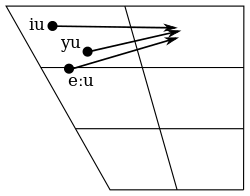

While [eɪ, øʏ, oʊ] occur only in Northern Standard Dutch and regional Netherlands Standard Dutch, all varieties of Standard Dutch have phonetic diphthongs [iu, yu, ui, eːu, ɔi, oːi, ɑi, aːi]. Phonemically, they are considered to be sequences of /iʋ, yʋ, uj, eːʋ, ɔj, oːj, ɑj, aːj/ by Geert Booij and as monosyllabic sequences /iu, yu, ui, eːu, oːi, aːi/ by Beverley Collins and Inger Mees (they do not comment on [ɔi] and [ɑi]).[87][88] This article adopts the former analysis.

In Northern Standard Dutch, the second elements of [iu, yu, eːu] can be labiodental [iʋ, yʋ, eːʋ]. This is especially common in intervocalic positions.[63]

In Northern Standard Dutch and regional Netherlands Standard Dutch, the close-mid elements of [eːu, oːi] may be subject to the same kind of diphthongization as /eː, oː/, so they may be actually triphthongs with two closing elements [eɪu, oʊi] ([eːu] can instead be [eɪʋ], a closing diphthong followed by [ʋ]). In Rotterdam, [oːi] can be phonetically [əʊi], with a central starting point.[89][90]

[aːi] is realized with more prominence on the first element according to Booij and with equal prominence on both elements according to Collins and Mees. Other diphthongs have more prominence on the first element.[89][91]

The endpoints of these diphthongs tend to be slightly more central ([ï, ü]) than cardinal [i, u]. They tend to be higher than the endpoints of the phonemic diphthongs /ɛi, œy, ɔu/.[92]

Example words for vowels and diphthongs

| Phoneme | Phonetic IPA | Orthography | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ɪ | kip | 'chicken' | |

| i | biet vier |

'beetroot' 'four' | |

| iː | analyse | 'analysis' | |

| ʏ | hut | 'cabin' | |

| y | fuut duur |

'grebe' 'expensive' | |

| yː | centrifuge | 'centrifuge' | |

| u | hoed invoering |

'hat' 'introduction' | |

| uː | cruise | 'cruise' | |

| ɛ | bed | 'bed' | |

| ɛː | blèr | 'yell' | |

| eː | beet (north) beet (Belgium) leerstelling (north) leerstelling (Belgium) |

'bit'(past form of to bite) 'dogma' | |

| ə | de | 'the' | |

| œː | oeuvre | 'oeuvre' | |

| øː | neus (north) neus (Belgium) scheur (north) scheur (Belgium) |

'nose' 'crack' | |

| ɔ | bot | 'bone' | |

| ɔː | roze | 'pink' | |

| oː | boot (north) boot (Belgium) Noordzee (north) Noordzee (Belgium) |

'boat' 'North Sea' | |

| ɑ | bad | 'bath' | |

| aː | zaad | 'seed' | |

| ɛi | Argentijn (north) Argentijn (Belgium) |

'Argentine' | |

| œy | uit ui |

'out' 'onion' | |

| ɔu | fout (north) fout (Belgium) |

'mistake' | |

| ɑi | ai | 'ouch' | |

| ɔi | hoi | 'hi' | |

| iu | nieuw | 'new' | |

| yu | duw | 'push' | |

| ui | groei | 'growth' | |

| eːu | leeuw | 'lion' | |

| oːi | mooi | 'nice' | |

| aːi | haai | 'shark' |