| |

| Long title | An Act Entitled The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | ACA, PPACA |

| Nicknames | Obamacare, Affordable Care Act, Health Insurance Reform, Healthcare Reform |

| Enacted by | the 111th United States Congress |

| Effective | March 23, 2010 Most major provisions phased in by January 2014; remaining provisions phased in by 2020; penalty enforcing individual mandate set at $0 starting 2019 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 111–148 |

| Statutes at Large | 124 Stat. 119 through 124 Stat. 1025 (906 pages) |

| Codification | |

| Acts amended | Public Health Service Act |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 Comprehensive 1099 Taxpayer Protection and Repayment of Exchange Subsidy Overpayments Act of 2011 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 | |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

| |

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), formally known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) and colloquially as Obamacare, is a landmark U.S. federal statute enacted by the 111th United States Congress and signed into law by President Barack Obama on March 23, 2010. Together with the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 amendment, it represents the U.S. healthcare system's most significant regulatory overhaul and expansion of coverage since the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.[1][2][3][4]

The ACA's major provisions came into force in 2014. By 2016, the uninsured share of the population had roughly halved, with estimates ranging from 20 to 24 million additional people covered.[5][6] The law also enacted a host of delivery system reforms intended to constrain healthcare costs and improve quality. After it went into effect, increases in overall healthcare spending slowed, including premiums for employer-based insurance plans.[7]

The increased coverage was due, roughly equally, to an expansion of Medicaid eligibility and to changes to individual insurance markets. Both received new spending, funded through a combination of new taxes and cuts to Medicare provider rates and Medicare Advantage. Several Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports said that overall these provisions reduced the budget deficit, that repealing ACA would increase the deficit,[8][9] and that the law reduced income inequality by taxing primarily the top 1% to fund roughly $600 in benefits on average to families in the bottom 40% of the income distribution.[10]

The act largely retained the existing structure of Medicare, Medicaid, and the employer market, but individual markets were radically overhauled.[1][11] Insurers were made to accept all applicants without charging based on preexisting conditions or demographic status (except age). To combat the resultant adverse selection, the act mandated that individuals buy insurance (or pay a monetary penalty) and that insurers cover a list of "essential health benefits".

Before and after enactment the ACA faced strong political opposition, calls for repeal and legal challenges. In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court ruled that states could choose not to participate in the law's Medicaid expansion, but upheld the law as a whole.[12] The federal health insurance exchange, HealthCare.gov, faced major technical problems at the beginning of its rollout in 2013. Polls initially found that a plurality of Americans opposed the act, although its individual provisions were generally more popular.[13] By 2017, the law had majority support.[14] The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 set the individual mandate penalty at $0 starting in 2019.[15] This raised questions about whether the ACA was still constitutional.[16][17][18] In June 2021, the Supreme Court upheld the ACA for the third time in California v. Texas.[19]

Provisions

ACA amended the Public Health Service Act of 1944 and inserted new provisions on affordable care into Title 42 of the United States Code.[1][2][3][20][4] The individual insurance market was radically overhauled, and many of the law's regulations applied specifically to this market,[1] while the structure of Medicare, Medicaid, and the employer market were largely retained.[2] Some regulations applied to the employer market, and the law also made delivery system changes that affected most of the health care system.[2]

Insurance regulations: individual policies

All new individual major medical health insurance policies sold to individuals and families faced new requirements.[21] The requirements took effect on January 1, 2014. They include:

- Guaranteed issue prohibits insurers from denying coverage to individuals due to preexisting conditions.[22]

- States were required to ensure the availability of insurance for individual children who did not have coverage via their families.

- A partial community rating allows premiums to vary only by age and location, regardless of preexisting conditions. Premiums for older applicants can be no more than three times those for the youngest.[23]

- Essential health benefits must be provided. The National Academy of Medicine defines the law's "essential health benefits" as "ambulatory patient services; emergency services; hospitalization; maternity and newborn care; mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment; prescription drugs; rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices; laboratory services; preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management; and pediatric services, including oral and vision care"[24][25] and others[26] rated Level A or B[27] by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.[28] In determining essential benefits, the law required that standard benefits should offer at least that of a "typical employer plan".[29] States may require additional services.[30]

- Preventive care and screenings for women.[31] "[A]ll Food and Drug Administration approved contraceptive methods, sterilization procedures, and patient education and counseling for all women with reproductive capacity".[32] This mandate applies to all employers and educational institutions except for religious organizations.[33][34] These regulations were included on the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine.[35][36]

- Annual and lifetime coverage caps on essential benefits were banned.[37][38][39]

- Insurers are forbidden from dropping policyholders when they become ill.[40][41]

- All policies must provide an annual maximum out-of-pocket (MOOP) payment cap for an individual's or family's medical expenses (excluding premiums). After the MOOP payment is reached, all remaining costs must be paid by the insurer.[42]

- Preventive care, vaccinations and medical screenings cannot be subject to co-payments, co-insurance or deductibles.[43][44][45] Specific examples of covered services include: mammograms and colonoscopies, wellness visits, gestational diabetes screening, HPV testing, STI counseling, HIV screening and counseling, contraceptive methods, breastfeeding support/supplies and domestic violence screening and counseling.[46]

- The law established four tiers of coverage: bronze, silver, gold and platinum. All categories offer essential health benefits. The categories vary in their division of premiums and out-of-pocket costs: bronze plans have the lowest monthly premiums and highest out-of-pocket costs, while platinum plans are the reverse.[29][47] The percentages of health care costs that plans are expected to cover through premiums (as opposed to out-of-pocket costs) are, on average: 60% (bronze), 70% (silver), 80% (gold), and 90% (platinum).[48]

- Insurers are required to implement an appeals process for coverage determination and claims on all new plans.[40]

- Insurers must spend at least 80–85% of premium dollars on health costs; rebates must be issued if this is violated.[49][50]

Individual mandate

The individual mandate[51] required everyone to have insurance or pay a penalty. The mandate and limits on open enrollment[52][53] were designed to avoid the insurance death spiral, minimize the free rider problem and prevent the healthcare system from succumbing to adverse selection.

The mandate was intended to increase the size and diversity of the insured population, including more young and healthy participants to broaden the risk pool, spreading costs.[54]

Among the groups who were not subject to the individual mandate are:

- Illegal immigrants, estimated at 8 million—or roughly a third of the 23 million projection—are ineligible for insurance subsidies and Medicaid.[55][56] They remain eligible for emergency services.

- Medicaid-eligible citizens not enrolled in Medicaid.[57]

- Citizens whose insurance coverage would cost more than 8% of household income.[57]

- Citizens who live in states that opt-out of Medicaid expansion and who qualify for neither existing Medicaid coverage nor subsidized coverage.[58]

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017,[59] set to $0 the penalty for not complying with the individual mandate, starting in 2019.[15]

Exchanges

ACA mandated that health insurance exchanges be provided for each state. The exchanges are regulated, largely online marketplaces, administered by either federal or state governments, where individuals, families and small businesses can purchase private insurance plans.[60][61][62] Exchanges first offered insurance for 2014. Some exchanges also provide access to Medicaid.[63][64]

States that set up their own exchanges have some discretion on standards and prices.[65][66] For example, states approve plans for sale, and thereby influence (through negotiations) prices. They can impose additional coverage requirements—such as abortion.[67] Alternatively, states can make the federal government responsible for operating their exchanges.[65]

Premium subsidies

Individuals whose household incomes are between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level (FPL) are eligible to receive federal subsidies for premiums for policies purchased on an ACA exchange, provided they are not eligible for Medicare, Medicaid, the Children's Health Insurance Program, or other forms of public assistance health coverage, and do not have access to affordable coverage (no more than 9.86% of income for the employee's coverage) through their own or a family member's employer.[68][69][70] Households below the federal poverty level are not eligible to receive these subsidies. Lawful Residents and some other legally present immigrants whose household income is below 100% FPL and are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid are eligible for subsidies if they meet all other eligibility requirements.[71][68] Married people must file taxes jointly to receive subsidies. Enrollees must have U.S. citizenship or proof of legal residency to obtain a subsidy.

The subsidies for an ACA plan purchased on an exchange stop at 400% of the federal poverty level (FPL). According to the Kaiser Foundation, this results in a sharp "discontinuity of treatment" at 400% FPL, which is sometimes called the "subsidy cliff".[72] After-subsidy premiums for the second lowest cost silver plan (SCLSP) just below the cliff are 9.86% of income in 2019.[73]

Subsidies are provided as an advanceable, refundable tax credit.[74][75]

The amount of subsidy is sufficient to reduce the premium for the second-lowest-cost silver plan (SCLSP) on an exchange cost a sliding-scale percentage of income. The percentage is based on the percent of federal poverty level (FPL) for the household, and varies slightly from year to year. In 2019, it ranged from 2.08% of income (100%-133% FPL) to 9.86% of income (300%-400% FPL).[70] The subsidy can be used for any plan available on the exchange, but not catastrophic plans. The subsidy may not exceed the premium for the purchased plan.

(In this section, the term "income" refers to modified adjusted gross income.[68][76])

Small businesses are eligible for a tax credit provided they enroll in the SHOP Marketplace.[77]

| Income % of federal poverty level | Premium cap as a share of income | Incomea | Maximumb annual net premium after subsidy (second-lowest-cost silver plan) |

Maximum out-of-pocket |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 133% | 3.11% of income | $33,383 | $1,038 | $5,200 |

| 150% | 4.15% of income | $37,650 | $1,562 | $5,200 |

| 200% | 6.54% of income | $50,200 | $3,283 | $5,200 |

| 250% | 8.36% of income | $62,750 | $5,246 | $12,600 |

| 300% | 9.86% of income | $75,300 | $7,425 | $15,800 |

| 400% | 9.86% of income | $100,400 | $9,899 | $15,800 |

|

a.^ In 2019, the federal poverty level was $25,100 for family of four (outside of Alaska and Hawaii). b.^ If the premium for the second lowest cost silver plan (SLCSP) is greater than the amount in this column, the amount of the premium subsidy will be such that it brings the net cost of the SCLSP down to the amount in this column. Otherwise, there will be no subsidy, and the SLCSP premium will (of course) be no more than (usually less than) the amount in this column. Note: The numbers in the table do not apply for Alaska and Hawaii. | ||||

Cost-sharing reduction subsidies

As written, ACA mandated that insurers reduce copayments and deductibles for ACA exchange enrollees earning less than 250% of the FPL. Medicaid recipients were not eligible for the reductions.

So-called cost-sharing reduction (CSR) subsidies were to be paid to insurance companies to fund the reductions. During 2017, approximately $7 billion in CSR subsidies were to be paid, versus $34 billion for premium tax credits.[78]

The latter was defined as mandatory spending that does not require an annual Congressional appropriation. CSR payments were not explicitly defined as mandatory. This led to litigation and disruption later.[further explanation needed]

Risk management

ACA implemented multiple approaches to helping mitigate the disruptions to insurers that came with its many changes.

Risk corridors

The risk-corridor program was a temporary risk management device.[79]: 1 It was intended to encourage reluctant insurers into ACA insurance market from 2014 to 2016. For those years the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) would cover some of the losses for insurers whose plans performed worse than they expected. Loss-making insurers would receive payments paid for in part by profit-making insurers.[80][81][attribution needed] Similar risk corridors had been established for the Medicare prescription drug benefit.[82]

While many insurers initially offered exchange plans, the program did not pay for itself as planned, losing up to $8.3 billion for 2014 and 2015. Authorization had to be given so DHHS could pay insurers from "general government revenues".[attribution needed] However, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014 (H.R. 3547) stated that no funds "could be used for risk-corridor payments".[83][attribution needed] leaving the government in a potential breach of contract with insurers who offered qualified health plans.[84]

Several insurers sued the government at the United States Court of Federal Claims to recover the funds believed owed to them under the Risk Corridors program. While several were summarily closed, in the case of Moda Health v the United States, Moda Health won a $214-million judgment in February 2017. Federal Claims judge Thomas C. Wheeler stated, "the Government made a promise in the risk corridors program that it has yet to fulfill. Today, the court directs the Government to fulfill that promise. After all, to say to [Moda], 'The joke is on you. You shouldn't have trusted us,' is hardly worthy of our great government."[85] Moda Health's case was appealed by the government to the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit along with the appeals of the other insurers; here, the Federal Circuit reversed the Moda Health ruling and ruled across all the cases in favor of the government, that the appropriations riders ceded the government from paying out remain money due to the insurers. The Supreme Court reversed this ruling in the consolidated case, Maine Community Health Options v. United States, reaffirming as with Judge Wheeler that the government had a responsibility to pay those funds under the ACA and the use of riders to de-obligate its from those payments was illegal.[86]

Reinsurance

The temporary reinsurance program is meant to stabilize premiums by reducing the incentive for insurers to raise premiums due to concerns about higher-risk enrollees. Reinsurance was based on retrospective costs rather than prospective risk evaluations. Reinsurance was available from 2014 through 2016.[87]

Risk adjustment

Risk adjustment involves transferring funds from plans with lower-risk enrollees to plans with higher-risk enrollees. It was intended to encourage insurers to compete based on value and efficiency rather than by attracting healthier enrollees. Of the three risk management programs, only risk adjustment was permanent. Plans with low actuarial risk compensate plans with high actuarial risk.[87]

Medicaid expansion

ACA revised and expanded Medicaid eligibility starting in 2014. All U.S. citizens and legal residents with income up to 133% of the poverty line, including adults without dependent children, would qualify for coverage in any state that participated in the Medicaid program. The federal government was to pay 100% of the increased cost in 2014, 2015 and 2016; 95% in 2017, 94% in 2018, 93% in 2019, and 90% in 2020 and all subsequent years.[88][89][90][91] A 5% "income disregard" made the effective income eligibility limit for Medicaid 138% of the poverty level.[92] However, the Supreme Court ruled in NFIB v. Sebelius that this provision of ACA was coercive, and that states could choose to continue at pre-ACA eligibility levels.

Medicare savings

Medicare reimbursements were reduced to insurers and drug companies for private Medicare Advantage policies that the Government Accountability Office and Medicare Payment Advisory Commission found to be excessively costly relative to standard Medicare;[93][94] and to hospitals that failed standards of efficiency and care.[93]

Taxes

Medicare taxes

Income from self-employment and wages of single individuals in excess of $200,000 annually are subjected to an additional tax of 0.9%. The threshold amount is $250,000 for a married couple filing jointly (threshold applies to their total compensation), or $125,000 for a married person filing separately.[95]

In ACA's companion legislation, the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010, an additional tax of 3.8% was applied to unearned income, specifically the lesser of net investment income and the amount by which adjusted gross income exceeds the above income limits.[96]

Excise taxes

ACA included an excise tax of 40% ("Cadillac tax") on total employer premium spending in excess of specified dollar amounts (initially $10,200 for single coverage and $27,500 for family coverage[97]) indexed to inflation. This tax was originally scheduled to take effect in 2018, but was delayed until 2020 by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 and again to 2022. The excise tax on high-cost health plans was completely repealed as part of H.R.1865 - Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020.

Excise taxes totaling $3 billion were levied on importers and manufacturers of prescription drugs. An excise tax of 2.3% on medical devices and a 10% excise tax on indoor tanning services were applied as well.[98] The tax was repealed in late 2019.[99]

SCHIP

The State Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) enrollment process was simplified.[100][101]

Dependents

Beginning September 23, 2010, dependents were permitted to remain on their parents' insurance plan until their 26th birthday, including dependents who no longer lived with their parents, are not a dependent on a parent's tax return, are no longer a student, or are married.[102][103]

Employer mandate

Businesses that employ fifty or more people but do not offer health insurance to their full-time employees are assessed additional tax if the government has subsidized a full-time employee's healthcare through tax deductions or other means. This is commonly known as the employer mandate.[104][105] This provision was included to encourage employers to continue providing insurance once the exchanges began operating.[106]

Delivery system reforms

The act includes delivery system reforms intended to constrain costs and improve quality. These include Medicare payment changes to discourage hospital-acquired conditions and readmissions, bundled payment initiatives, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, the Independent Payment Advisory Board, and accountable care organizations.

Hospital quality

Health care cost/quality initiatives included incentives to reduce hospital infections, adopt electronic medical records, and to coordinate care and prioritize quality over quantity.[107]

Bundled payments

Medicare switched from fee-for-service to bundled payments.[108][109] A single payment was to be paid to a hospital and a physician group for a defined episode of care (such as a hip replacement) rather than separate payments to individual service providers.[110]

Accountable care organizations

The Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) was established by section 3022 of the Affordable Care Act. It is the program by which an accountable care organization interacts with the federal government, and by which accountable care organizations can be created.[111] It is a fee-for-service model.

The Act allowed the creation of accountable care organizations (ACOs), which are groups of doctors, hospitals and other providers that commit to give coordinated care to Medicare patients. ACOs were allowed to continue using fee-for-service billing. They receive bonus payments from the government for minimizing costs while achieving quality benchmarks that emphasize prevention and mitigation of chronic disease. Missing cost or quality benchmarks subjected them to penalties.[112]

Unlike health maintenance organizations, ACO patients are not required to obtain all care from the ACO. Also, unlike HMOs, ACOs must achieve quality-of-care goals.[112]

Medicare drug benefit (Part D)

Medicare Part D participants received a 50% discount on brand name drugs purchased after exhausting their initial coverage and before reaching the catastrophic-coverage threshold.[113] By 2020, the "doughnut hole" would be completely filled.[114]

State waivers

From 2017 onwards, states can apply for a "waiver for state innovation" which allows them to conduct experiments that meet certain criteria.[115] To obtain a waiver, a state must pass legislation setting up an alternative health system that provides insurance at least as comprehensive and as affordable as ACA, covers at least as many residents and does not increase the federal deficit.[116] These states can escape some of ACA's central requirements, including the individual and employer mandates and the provision of an insurance exchange.[117] The state would receive compensation equal to the aggregate amount of any federal subsidies and tax credits for which its residents and employers would have been eligible under ACA, if they cannot be paid under the state plan.[115]

Other insurance provisions

The Community Living Assistance Services and Supports Act (or CLASS Act) established a voluntary and public long-term care insurance option for employees,[118][119][120] The program was abolished as impractical without ever having taken effect.[121]

Consumer Operated and Oriented Plans (CO-OP), member-governed non-profit insurers, could start providing health care coverage, based on a 5-year federal loan.[122] As of 2017, only four of the original 23 co-ops were still in operation.[123]

Nutrition labeling requirements

Nutrition labeling requirements officially took effect in 2010, but implementation was delayed, and they actually took effect on May 7, 2018.[124]

Legislative history

ACA followed a long series of unsuccessful attempts by one party or the other to pass major insurance reforms. Innovations were limited to health savings accounts (2003), medical savings accounts (1996) or flexible spending accounts, which increased insurance options, but did not materially expand coverage. Health care was a major factor in multiple elections, but until 2009, neither party had the votes to overcome the other's opposition.

Individual mandate

The concept of an individual mandate goes back to at least 1989, when The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think-tank, proposed an individual mandate as an alternative to single-payer health care.[125][126] It was championed for a time by conservative economists and Republican senators as a market-based approach to healthcare reform on the basis of individual responsibility and avoidance of free rider problems. Specifically, because the 1986 Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) requires any hospital participating in Medicare (nearly all do) to provide emergency care to anyone who needs it, the government often indirectly bore the cost of those without the ability to pay.[127][128][129]

President Bill Clinton proposed a major healthcare reform bill in 1993[128] that ultimately failed.[130] Clinton negotiated a compromise with the 105th Congress to instead enact the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) in 1997.[citation needed] The failed Clinton plan included a mandate for employers to provide health insurance to all employees through a regulated marketplace of health maintenance organizations. Republican senators proposed an alternative that would have required individuals, but not employers, to buy insurance.

The 1993 Republican Health Equity and Access Reform Today (HEART) Act, contained a "universal coverage" requirement with a penalty for noncompliance—an individual mandate—as well as subsidies to be used in state-based 'purchasing groups'.[131] Advocates included prominent Republican senators such as John Chafee, Orrin Hatch, Chuck Grassley, Bob Bennett and Kit Bond.[132][133] The 1994 Republican Consumer Choice Health Security Act, initially contained an individual mandate with a penalty provision;[134] however, author Don Nickles subsequently removed the mandate, stating, "government should not compel people to buy health insurance".[135] At the time of these proposals, Republicans did not raise constitutional issues; Mark Pauly, who helped develop a proposal that included an individual mandate for George H. W. Bush, remarked, "I don't remember that being raised at all. The way it was viewed by the Congressional Budget Office in 1994 was, effectively, as a tax."[125]

In 2006, an insurance expansion bill was enacted at the state level in Massachusetts. The bill contained both an individual mandate and an insurance exchange. Republican Governor Mitt Romney used a line-item veto on some provisions, and the Democratic legislature overrode some of his changes (including the mandate).[137] Romney's implementation of the 'Health Connector' exchange and individual mandate in Massachusetts was at first lauded by Republicans. During Romney's 2008 presidential campaign, Senator Jim DeMint praised Romney's ability to "take some good conservative ideas, like private health insurance, and apply them to the need to have everyone insured". Romney said of the individual mandate: "I'm proud of what we've done. If Massachusetts succeeds in implementing it, then that will be the model for the nation."[138]

In 2007 Republican Senator Bob Bennett and Democratic Senator Ron Wyden introduced the Healthy Americans Act, which featured an individual mandate and state-based, regulated insurance markets called "State Health Help Agencies".[129][138] The bill attracted bipartisan support, but died in committee. Many of its sponsors and co-sponsors remained in Congress during the 2008 healthcare debate.[139]

By 2008 many Democrats were considering this approach as the basis for healthcare reform. Experts said the legislation that eventually emerged from Congress in 2009 and 2010 bore similarities to the 2007 bill[131] and that it took ideas from the Massachusetts reforms.[140]

Academic foundation

A driving force behind Obama's healthcare reform was Peter Orszag, Director of the Office of Management and Budget.[141] Obama called Orszag his "healthcare czar" because of his knowledge of healthcare reform.[142] Orszag had previously been director of the Congressional Budget Office, and under his leadership the agency had focused on using cost analysis to create an affordable and effective approach to health care reform. Orszag claimed that healthcare reform became Obama's top agenda item because he wanted it to be his legacy.[143] According to an article by Ryan Lizza in The New Yorker, the core of "the Obama budget is Orszag's belief [in]...a government empowered with research on the most effective medical treatments". Obama bet "his presidency on Orszag's thesis of comparative effectiveness."[144] Orszag's policies were influenced by an article in The Annals of Internal Medicine[145] co-authored by Elliott S. Fisher, David Wennberg and others. The article presented strong evidence based on the co-authors' research that numerous procedures, therapies and tests were being delivered with scant evidence of their medical value. If those procedures and tests could be eliminated, this evidence suggested, medical costs might provide the savings to give healthcare to the uninsured population.[146] After reading a New Yorker article that used the "Dartmouth findings"[147] to compare two counties in Texas with enormous variations in Medicare costs using hard data, Obama directed that his entire staff read it.[148] More than anything else, the Dartmouth data intrigued Obama[149] since it gave him an academic rationale for reshaping medicine.[150]

The concept of comparing the effectiveness of healthcare options based on hard data ("comparative effectiveness" and "evidence-based medicine") was pioneered by John E. Wennberg, founder of The Dartmouth Institute, co-founder of The Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making and senior advisor to Health Dialog Inc., a venture that he and his researchers created to help insurers implement the Dartmouth findings.

Healthcare debate, 2008–10

Healthcare reform was a major topic during the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries. As the race narrowed, attention focused on the plans presented by the two leading candidates, Hillary Clinton and the eventual nominee, Barack Obama. Each candidate proposed a plan to cover the approximately 45 million Americans estimated to not have health insurance at some point each year. Clinton's proposal would have required all Americans to obtain coverage (in effect, an individual mandate), while Obama's proposal provided a subsidy without a mandate.[151][152]

During the general election, Obama said fixing healthcare would be one of his top four priorities as president.[153] Obama and his opponent, Senator John McCain, both proposed health insurance reforms, though their plans differed. McCain proposed tax credits for health insurance purchased in the individual market, which was estimated to reduce the number of uninsured people by about 2 million by 2018. Obama proposed private and public group insurance, income-based subsidies, consumer protections, and expansions of Medicaid and SCHIP, which was estimated at the time to reduce the number of uninsured people by 33.9 million by 2018 at a higher cost.[154]

Obama announced to a joint session of Congress in February 2009 his intent to work with Congress to construct a plan for healthcare reform.[155][156] By July, a series of bills were approved by committees within the House of Representatives.[157] On the Senate side, from June to September, the Senate Finance Committee held a series of 31 meetings to develop a proposal. This group—in particular, Democrats Max Baucus, Jeff Bingaman and Kent Conrad, along with Republicans Mike Enzi, Chuck Grassley and Olympia Snowe—met for more than 60 hours, and the principles they discussed, in conjunction with the other committees, became the foundation of a Senate bill.[158][159][160]

Congressional Democrats and health policy experts, such as MIT economics professor Jonathan Gruber[161] and David Cutler, argued that guaranteed issue would require both community rating and an individual mandate to ensure that adverse selection and/or "free riding" would not result in an insurance "death spiral".[162] They chose this approach after concluding that filibuster-proof support in the Senate was not present for more progressive plans such as single-payer. By deliberately drawing on bipartisan ideas—the same basic outline was supported by former Senate Majority Leaders Howard Baker, Bob Dole, Tom Daschle and George J. Mitchell—the bill's drafters hoped to garner the necessary votes.[163][164]

However, following the incorporation of an individual mandate into the proposal, Republicans threatened to filibuster any bill that contained it.[125] Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, who led the Republican response, concluded Republicans should not support the bill.[165]

Republican senators, including those who had supported earlier proposals with a similar mandate, began to describe the mandate as "unconstitutional". Journalist Ezra Klein wrote in The New Yorker, "a policy that once enjoyed broad support within the Republican Party suddenly faced unified opposition."[129]

The reform attracted attention from lobbyists,[166] including deals between lobby groups and the advocates to win the support of groups who had opposed past proposals.[167][168][169]

During the August 2009 summer congressional recess, many members went back to their districts and held town hall meetings on the proposals. The nascent Tea Party movement organized protests and many conservative groups and individuals attended the meetings to oppose the proposed reforms.[156] Threats were made against members of Congress over the course of the debate.[170]

In September 2009 Obama delivered another speech to a joint session of Congress supporting the negotiations.[171] On November 7, the House of Representatives passed the Affordable Health Care for America Act on a 220–215 vote and forwarded it to the Senate for passage.[156]

Senate

The Senate began work on its own proposals while the House was still working. The United States Constitution requires all revenue-related bills to originate in the House.[172] To formally comply with this requirement, the Senate repurposed H.R. 3590, a bill regarding housing tax changes for service members.[173] It had been passed by the House as a revenue-related modification to the Internal Revenue Code. The bill became the Senate's vehicle for its healthcare reform proposal, discarding the bill's original content.[174] The bill ultimately incorporated elements of proposals that were reported favorably by the Senate Health and Finance committees. With the Republican Senate minority vowing to filibuster, 60 votes would be necessary to pass the Senate.[175] At the start of the 111th Congress, Democrats had 58 votes. The Minnesota Senate election was ultimately won by Democrat Al Franken, making 59. Arlen Specter switched to the Democratic party in April 2009, giving them 60 seats, enough to end a filibuster.

Negotiations were undertaken attempting to satisfy moderate Democrats and to bring Republican senators aboard; particular attention was given to Republicans Bennett, Enzi, Grassley and Snowe.

After the Finance Committee vote on October 15, negotiations turned to moderate Democrats. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid focused on satisfying centrists. The holdouts came down to Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, an independent who caucused with Democrats, and conservative Nebraska Democrat Ben Nelson. Lieberman's demand that the bill not include a public option[162][176] was met,[177] although supporters won various concessions, including allowing state-based public options such as Vermont's failed Green Mountain Care.[177][178]

The White House and Reid addressed Nelson's concerns[179] during a 13-hour negotiation with two concessions: a compromise on abortion, modifying the language of the bill "to give states the right to prohibit coverage of abortion within their own insurance exchanges", which would require consumers to pay for the procedure out of pocket if the state so decided; and an amendment to offer a higher rate of Medicaid reimbursement for Nebraska.[156][180] The latter half of the compromise was derisively termed the "Cornhusker Kickback"[181] and was later removed.

On December 23, the Senate voted 60–39 to end debate on the bill: a cloture vote to end the filibuster.[182] The bill then passed, also 60–39, on December 24, 2009, with all Democrats and two independents voting for it, and all Republicans against (except Jim Bunning, who did not vote).[183] The bill was endorsed by the American Medical Association and AARP.[184]

On January 19, 2010, Massachusetts Republican Scott Brown was elected to the Senate in a special election to replace the recently deceased Ted Kennedy, having campaigned on giving the Republican minority the 41st vote needed to sustain Republican filibusters.[156][185][186] Additionally, the symbolic importance of losing Kennedy's traditionally Democratic Massachusetts seat made many Congressional Democrats concerned about the political cost of the bill.[187][188]

House

With Democrats no longer able to get the 60 votes to break a filibuster in the Senate, White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel argued that Democrats should scale back to a less ambitious bill, but House Speaker Nancy Pelosi pushed back, dismissing more moderate reform as "Kiddie Care".[189][190]

Obama remained insistent on comprehensive reform. The news that Anthem in California intended to raise premium rates for its patients by as much as 39% gave him new evidence of the need for reform.[189][190] On February 22, he laid out a "Senate-leaning" proposal to consolidate the bills.[191] He held a meeting with both parties' leaders on February 25. The Democrats decided the House would pass the Senate's bill, to avoid another Senate vote.

House Democrats had expected to be able to negotiate changes in a House–Senate conference before passing a final bill. Since any bill that emerged from conference that differed from the Senate bill would have to pass the Senate over another Republican filibuster, most House Democrats agreed to pass the Senate bill on condition that it be amended by a subsequent bill.[188] They drafted the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act, which could be passed by the reconciliation process.[189][192][193]

Per the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, reconciliation cannot be subject to a filibuster. But reconciliation is limited to budget changes, which is why the procedure was not used to pass ACA in the first place; the bill had inherently non-budgetary regulations.[194][195] Although the already-passed Senate bill could not have been passed by reconciliation, most of House Democrats' demands were budgetary: "these changes—higher subsidy levels, different kinds of taxes to pay for them, nixing the Nebraska Medicaid deal—mainly involve taxes and spending. In other words, they're exactly the kinds of policies that are well-suited for reconciliation."[192]

The remaining obstacle was a pivotal group of pro-life Democrats led by Bart Stupak who were initially reluctant to support the bill. The group found the possibility of federal funding for abortion significant enough to warrant opposition. The Senate bill had not included language that satisfied their concerns, but they could not address abortion in the reconciliation bill as it would be non-budgetary. Instead, Obama issued Executive Order 13535, reaffirming the principles in the Hyde Amendment.[196] This won the support of Stupak and members of his group and assured the bill's passage.[193][197] The House passed the Senate bill with a 219–212 vote on March 21, 2010, with 34 Democrats and all 178 Republicans voting against it.[198] It passed the second bill, by 220–211, the same day (with the Senate passing this bill via reconciliation by 56-43 a few days later). The day after the passage of ACA, March 22, Republicans introduced legislation to repeal it.[199] Obama signed ACA into law on March 23, 2010.[20]

Post-enactment

Since passage, Republicans have voted to repeal all or parts of the Affordable Care Act more than sixty times.[200]

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 eliminated the fine for violating the individual mandate, starting in 2019. (The requirement itself is still in effect.)[15] In 2019 Congress repealed the so-called "Cadillac" tax on health insurance benefits, an excise tax on medical devices, and the Health Insurance Tax.[99]

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, expanded subsidies for marketplace health plans. A continuation of these subsidies was introduced as part of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

Impact

Coverage

The law caused a significant reduction in the number and percentage of people without health insurance. The CDC reported that the percentage of people without health insurance fell from 16.0% in 2010 to 8.9% from January to June 2016.[201] The uninsured rate dropped in every congressional district in the U.S. from 2013 to 2015.[202] The Congressional Budget Office reported in March 2016 that approximately 12 million people were covered by the exchanges (10 million of whom received subsidies) and 11 million added to Medicaid. Another million were covered by ACA's "Basic Health Program", for a total of 24 million.[5] CBO estimated that ACA would reduce the net number of uninsured by 22 million in 2016, using a slightly different computation for the above figures totaling ACA coverage of 26 million, less 4 million for reductions in "employment-based coverage" and "non-group and other coverage".[5]

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) estimated that 20.0 million adults (aged 18–64) gained healthcare coverage via ACA as of February 2016;[6] similarly, the Urban Institute found in 2016 that 19.2 million non-elderly Americans gained health insurance coverage from 2010 to 2015.[203] In 2016, CBO estimated the uninsured at approximately 27 million people, or around 10% of the population or 7–8% excluding unauthorized immigrants.[5]

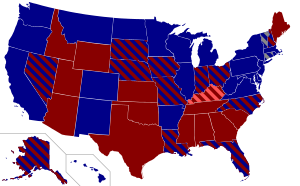

States that expanded Medicaid had a 7.3% uninsured rate on average in the first quarter of 2016, while those that did not had a 14.1% uninsured rate, among adults aged 18–64.[204] As of December 2016 32 states (including Washington DC) had adopted the Medicaid extension.[205]

A 2017 study found that the ACA reduced socioeconomic disparities in health care access.[206]

The Affordable Care Act reduced the percent of Americans between 18 and 64 who were uninsured from 22.3 percent in 2010 to 12.4 percent in 2016. About 21 million more people have coverage ten years after the enactment of the ACA.[207][208] Ten years after its enactment studies showed that the ACA also had a positive effect on health and caused a reduction in mortality.[208]

Taxes

Excise taxes from the Affordable Care Act raised $16.3 billion in fiscal year 2015. $11.3 billion came from an excise tax placed directly on health insurers based on their market share. Annual excise taxes totaling $3 billion were levied on importers and manufacturers of prescription drugs.

The Individual mandate tax was $695 per individual or $2,085 per family at a minimum, reaching as high as 2.5% of household income (whichever was higher). The tax was set to $0 beginning in 2019.[209]

In the fiscal year 2018, the individual and employer mandates yielded $4 billion each. Excise taxes on insurers and drug makers added $18 billion. Income tax surcharges produced 437 billion.[210]

ACA reduced income inequality measured after taxes, due to the income tax surcharges and subsidies.[211] CBO estimated that subsidies paid under the law in 2016 averaged $4,240 per person for 10 million individuals receiving them, roughly $42 billion. The tax subsidy for the employer market, was approximately $1,700 per person in 2016, or $266 billion total.[5]

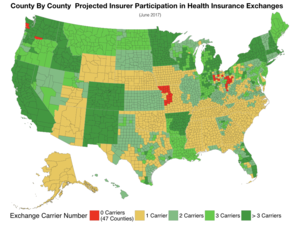

Insurance exchanges

As of August 2016, 15 states operated their own health insurance marketplace. Other states either used the federal exchange, or operated in partnership with or supported by the federal government.[212] By 2019, 12 states and Washington DC operated their own exchanges.[213]

Medicaid expansion in practice

As of December 2019, 37 states (including Washington DC) had adopted the Medicaid extension.[205] Those states that expanded Medicaid had a 7.3% uninsured rate on average in the first quarter of 2016, while the others had a 14.1% uninsured rate, among adults aged 18 to 64.[204] Following the Supreme Court ruling in 2012, which held that states would not lose Medicaid funding if they did not expand Medicaid under ACA, several states rejected the option. Over half the national uninsured population lived in those states.[214]

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) estimated that the cost of expansion was $6,366 per person for 2015, about 49 percent above previous estimates. An estimated 9 to 10 million people had gained Medicaid coverage, mostly low-income adults.[citation needed] The Kaiser Family Foundation estimated in October 2015 that 3.1 million additional people were not covered because of states that rejected the Medicaid expansion.[215][216]

In many states income thresholds were significantly below 133% of the poverty line.[217] Many states did not make Medicaid available to childless adults at any income level.[218] Because subsidies on exchange insurance plans were not available to those below the poverty line, such individuals had no new options.[219][220] For example, in Kansas, where only non-disabled adults with children and with an income below 32% of the poverty line were eligible for Medicaid, those with incomes from 32% to 100% of the poverty level ($6,250 to $19,530 for a family of three) were ineligible for both Medicaid and federal subsidies to buy insurance. Absent children, non-disabled adults were not eligible for Medicaid there.[214]

Studies of the impact of Medicaid expansion rejections calculated that up to 6.4 million people would have too much income for Medicaid but not qualify for exchange subsidies.[221] Several states argued that they could not afford the 10% contribution in 2020.[222][223][224] Some studies suggested rejecting the expansion would cost more due to increased spending on uncompensated emergency care that otherwise would have been partially paid for by Medicaid coverage,[225][226]

A 2016 study found that residents of Kentucky and Arkansas, which both expanded Medicaid, were more likely to receive health care services and less likely to incur emergency room costs or have trouble paying their medical bills. Residents of Texas, which did not accept the Medicaid expansion, did not see a similar improvement during the same period.[227][228] Kentucky opted for increased managed care, while Arkansas subsidized private insurance. Later Arkansas and Kentucky governors proposed reducing or modifying their programs. From 2013 to 2015, the uninsured rate dropped from 42% to 14% in Arkansas and from 40% to 9% in Kentucky, compared with 39% to 32% in Texas.[227][229]

A 2016 DHHS study found that states that expanded Medicaid had lower premiums on exchange policies, because they had fewer low-income enrollees, whose health on average is worse than that of those with higher income.[230]

In September 2019, the Census Bureau reported that states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA had considerably lower uninsured rates than states that did not. For example, for adults between 100% and 399% of poverty level, the uninsured rate in 2018 was 12.7% in expansion states and 21.2% in non-expansion states. Of the 14 states with uninsured rates of 10% or greater, 11 had not expanded Medicaid.[231] The drop in uninsured rates due to expanded Medicaid has broadened access to care among low-income adults, with post-ACA studies indicating an improvement in affordability, access to doctors, and usual sources of care.[232]

A study using national data from the Health Reform Monitoring Survey determined that unmet need due to cost and inability to pay medical bills significantly decreased among low-income (up to 138% FPL) and moderate-income (139-199% FPL) adults, with unmet need due to cost decreasing by approximately 11 percentage points among low-income adults by the second enrollment period.[232] Importantly, issues with cost-related unmet medical needs, skipped medications, paying medical bills, and annual out-of-pocket spending have been significantly reduced among low-income adults in Medicaid expansion states compared to non-expansion states.[232]

As well, expanded Medicaid has led to a 6.6% increase in physician visits by low-income adults, as well as increased usage of preventative care such as dental visits and cancer screenings among childless, low-income adults.[232] Improved health care coverage due to Medicaid expansion has been found in a variety of patient populations, such as adults with mental and substance use disorders, trauma patients, cancer patients, and people living with HIV.[233][234][235][236] Compared to 2011–13, in 2014 there was a 5.4 percentage point reduction in the uninsured rate of adults with mental disorders (from 21.3% to 15.9%) and a 5.1 percentage point reduction in the uninsured rate of adults with substance use disorders (from 25.9% to 20.8%); with increases in coverage occurring primarily through Medicaid.[236] Use of mental health treatment increased by 2.1 percentage points, from 43% to 45.1%.[236]

Among trauma patients nationwide, the uninsured rate has decreased by approximately 50%.[233] Adult trauma patients in expansion states experienced a 13.7 percentage point reduction in uninsured rates compared to adult trauma patients in non-expansion states, and an accompanying 7.4 percentage point increase in discharge to rehabilitation.[237] Following Medicaid expansion and dependent coverage expansion, young adults hospitalized for acute traumatic injury in Maryland experienced a 60% increase in rehabilitation, 25% reduction in mortality, and a 29.8% reduction in failure-to-rescue.[238] Medicaid expansion's swift impact on cancer patients was demonstrated in a study using the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program that evaluated more than 850,000 patients diagnosed with breast, lung, colorectal, prostate cancer, or thyroid cancer from 2010 to 2014. The study found that a cancer diagnosis in 2014 was associated with a 1.9 percentage-point absolute and 33.5% relative decrease in uninsured rates compared to a diagnosis made between 2010 and 2013.[235] Another study, using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program data from 2010 to 2014, found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a 6.4% net increase in early stage (in situ, local, or regional) diagnoses of all cancers combined.[239]

Data from the Centers for Disease and Prevention's (CDC) Medical Monitoring Project demonstrated that between 2009 and 2012, approximately 18% of people living with HIV (PLWH) who were actively receiving HIV treatment were uninsured[240] and that at least 40% of HIV-infected adults receiving treatment were insured through Medicaid and/or Medicare, programs they qualified for only once their disease was advanced enough to be covered as a disability under Social Security.[240] Expanded Medicaid coverage of PLWH has been positively associated with health outcomes such as viral suppression, retention of care, hospitalization rates, and morbidity at the time of hospitalization.[234] An analysis of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey data found a 2.8% annual increase in viral suppression rates among all PLWH from 2010 to 2015 due to Medicaid expansion.[241] In Nebraska, PLWH newly covered by Medicaid expansion in 2013-14 were four times more likely to be virally suppressed than PLWH who were eligible but remained uninsured.[241] As an early adopter of Medicaid expansion, Massachusetts found a 65% rate of viral suppression among all PLWH and an 85% rate among those retained in healthcare in 2014, both substantially higher than the national average.[241]

An analysis of hospital discharge data from 2012 to 2014 in four Medicaid expansion states and two non-expansion states revealed hospitalizations of uninsured PLWH fell from 13.7% to 5.5% in the four expansion states and rose from 14.5% to 15.7% in the two non-expansion states.[242] Importantly, uninsured PLWH were 40% more likely to die in the hospital than insured PLWH.[242] Other notable health outcomes associated with Medicaid expansion include improved glucose monitoring rates for patients with diabetes, better hypertension control, and reduced rates of major post-operative morbidity.[243]

A July 2019 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) indicated that states enacting Medicaid expansion exhibited statistically significant reductions in mortality rates.[244] From that study, states that took Medicaid expansion "saved the lives of at least 19,200 adults aged 55 to 64 over the four-year period from 2014 to 2017."[245] Further, 15,600 older adults died prematurely in the states that did not enact Medicaid expansion in those years according to the NBER research. "The lifesaving impacts of Medicaid expansion are large: an estimated 39 to 64 percent reduction in annual mortality rates for older adults gaining coverage."[245]

Due to many states' failure to expand, many Democrats co-sponsored the proposed 2021 Cover Now Act that would allow county and municipal governments to fund Medicaid expansion.[246]

Medicaid expansion by state

| State or territory | Status of expansion | Date of expansion | Health insurance marketplace | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | September 1, 2015 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Arkansas Health Connector, HealthCare.gov | State implemented expansion through a "private option" under a Section 1115 waiver through the Arkansas Health Care Independence Program (HCIP). Work requirement added in 2018 through Arkansas Works. Work requirement removed in 2021. Currently only state using "private option" as of 2022. | |

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Covered California, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Connect for Health Colorado, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Access Health CT, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov | ||

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Hawaii Health Connector, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2020 | Your Health Idaho, HealthCare.gov | Enacted through 2018 Idaho Proposition 2. | |

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Illinois Health Benefits Exchange, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | February 1, 2015 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Kynect, HealthCare.gov | Enacted through gubernatorial executive order | |

| In effect | July 1, 2016 | HealthCare.gov | Enacted through gubernatorial executive order | |

| In effect | January 10, 2019 | HealthCare.gov | Enacted through 2017 Maine Question 2, but implementation was delayed due to gubernatorial opposition. coverage retroactive to 7/2/2018. | |

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Maryland Health Connection, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Massachusetts Health Insurance Connector, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | April 1, 2014 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | MNsure, HealthCare.gov | ||

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | October 1, 2021 | HealthCare.gov | Enacted through 2020 Missouri Amendment 2, but applications were denied until October 1, 2021, due to legislative opposition to the amendment. coverage retroactive to 7/1/2021. | |

| In effect | January 1, 2016 | HealthCare.gov | Legislature enacted expansion with a work requirement; work requirement was due to take effect in January 2020 but never received federal approval. Current expansion is extended to June 2025. | |

| In effect | October 1, 2020 | HealthCare.gov | enacted through 2018 Nebraska Initiative 427. | |

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Nevada Health Link, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | August 15, 2014 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | New Mexico Health Insurance Exchange, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | NY State of Health, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| Expansion pending | June 2023 (expected) | HealthCare.gov | Legislature expanded Medicaid. Signed into law by Governor Roy Cooper. Expansion expected to go into effect when the state adopts a budget in June 2023.[247] | |

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | July 1, 2021 | HealthCare.gov | Enacted through 2020 Oklahoma State Question 802. | |

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Cover Oregon (2012–2015), HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2015 | Pennie, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | HealthSource RI, HealthCare.gov | ||

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov | ||

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov | ||

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov | ||

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2020 | HealthCare.gov | Enacted through 2018 Utah Proposition 3, but subsequently scaled back through legislative action to enforce a Section 1115 waiver for eligibility. | |

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Vermont Health Connect, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2019 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | Washington Healthplanfinder, HealthCare.gov | ||

| In effect | DC Health Link, HealthCare.gov | |||

| In effect | January 1, 2014 | HealthCare.gov | ||

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov | ||

| No expansion | N/A | HealthCare.gov |

Insurance costs

National health care expenditures rose faster than national income both before (2009–2013: 3.73%) and after (2014–2018: 4.82%) ACA's major provisions took effect.[249][248] Premium prices rose considerably before and after. For example, a study published in 2016 found that the average requested 2017 premium increase among 40-year-old non-smokers was about 9 percent, according to an analysis of 17 cities, although Blue Cross Blue Shield proposed increases of 40 percent in Alabama and 60 percent in Texas.[250] However, some or all these costs were offset by tax credits. For example, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported that for the second-lowest cost "Silver plan", a 40-year old non-smoker making $30,000 per year would pay effectively the same amount in 2017 as they did in 2016 (about $208/month) after the tax credit, despite a large increase in the list price. This was consistent nationally. In other words, the subsidies increased along with the premium price, fully offsetting the increases for subsidy-eligible enrollees.[251]

Premium cost increases in the employer market moderated after 2009. For example, healthcare premiums for those covered by employers rose by 69% from 2000 to 2005, but only 27% from 2010 to 2015,[7] with only a 3% increase from 2015 to 2016.[252] From 2008 to 2010 (before passage of ACA) health insurance premiums rose by an average of 10% per year.[253]

Several studies found that the financial crisis and accompanying recession could not account for the entirety of the slowdown and that structural changes likely shared at least partial credit.[254][255][256][257] A 2013 study estimated that changes to the health system had been responsible for about a quarter of the recent reduction in inflation.[258][clarification needed] Paul Krawzak claimed that even if cost controls succeed in reducing the amount spent on healthcare, such efforts on their own may be insufficient to outweigh the long-term burden placed by demographic changes, particularly the growth of the population on Medicare.[259]

In a 2016 review, Barack Obama claimed that from 2010 through 2014 mean annual growth in real per-enrollee Medicare spending was negative, down from a mean of 4.7% per year from 2000 through 2005 and 2.4% per year from 2006 to 2010; similarly, mean real per-enrollee growth in private insurance spending was 1.1% per year over the period, compared with a mean of 6.5% from 2000 through 2005 and 3.4% from 2005 to 2010.[260]

Deductibles and co-payments

A contributing factor to premium cost moderation was that the insured faced higher deductibles, copayments and out-of-pocket maximums. In addition, many employees chose to combine a health savings account with higher deductible plans, making the net impact of ACA difficult to determine precisely.

For the group market (employer insurance), a 2016 survey found that:

- Deductibles grew 63% from 2011 to 2016, while premiums increased 19% and worker earnings grew by 11%.

- In 2016, 4 in 5 workers had an insurance deductible, which averaged $1,478. For firms with less than 200 employees, the deductible averaged $2,069.

- The percentage of workers with a deductible of at least $1,000 grew from 10% in 2006 to 51% in 2016. The 2016 figure dropped to 38% after taking employer contributions into account.[261]

For the non-group market, of which two-thirds are covered by ACA exchanges, a survey of 2015 data found that:

- 49% had individual deductibles of at least $1,500 ($3,000 for family), up from 36% in 2014.

- Many exchange enrollees qualify for cost-sharing subsidies that reduce their net deductible.

- While about 75% of enrollees were "very satisfied" or "somewhat satisfied" with their choice of doctors and hospitals, only 50% had such satisfaction with their annual deductible.

- While 52% of those covered by ACA exchanges felt "well protected" by their insurance, in the group market 63% felt that way.[262]

Health outcomes

According to a 2014 study, ACA likely prevented an estimated 50,000 preventable patient deaths from 2010 to 2013.[263] Himmelstein and Woolhandler wrote in January 2017 that a rollback of ACA's Medicaid expansion alone would cause an estimated 43,956 deaths annually.[264]

According to the Kaiser Foundation, expanding Medicaid in the remaining states would cover up to 4.5 million persons.[265] A 2021 study found a significant decline in mortality rates in the states that opted in to the Medicaid expansion program compared with those states that did not do so. The study reported that states decisions' not to expand Medicaid resulted in approximately 15,600 excess deaths from 2014 through 2017.[266][267]

Dependent Coverage Expansion (DCE) under the ACA has had a demonstrable effect on various health metrics of young adults, a group with a historically low level of insurance coverage and utilization of care.[268] Numerous studies have shown the target age group gained private health insurance relative to an older group after the policy was implemented, with an accompanying improvement in having a usual source of care, reduction in out-of-pocket costs of high-end medical expenditures, reduction in frequency of Emergency Department visits, 3.5% increase in hospitalizations and 9% increase in hospitalizations with a psychiatric diagnosis, 5.3% increase in utilizing specialty mental health care by those with a probable mental illness, 4% increase in reporting excellent mental health, and a 1.5-6.2% increase in reporting excellent physical health.[268] Studies have also found that DCE was associated with improvements in cancer prevention, detection, and treatment among young adult patients.[239][269] A study of 10,010 women aged 18–26 identified through the 2008-12 National Health Interview Survey found that the likelihood of HPV vaccination initiation and completion increased by 7.7 and 5.8 percentage points respectively when comparing before and after October 1, 2010.[269] Another study using National Cancer Database (NCDB) data from 2007 to 2012 found a 5.5 percentage point decrease in late-stage (stages III/IV) cervical cancer diagnosis for women aged 21–25 after DCE, and an overall decrease of 7.3 percentage points in late-stage diagnosis compared to those aged 26–34.[239] A study using SEER Program data from 2007 to 2012 found a 2.7 percentage point increase in diagnosis at stage I disease for patients aged 19–25 compared with those aged 26–34 for all cancers combined.[239] Studies focusing on cancer treatment after DCE found a 12.8 percentage point increase in the receipt of fertility-sparing treatment among cervical cancer patients aged 21–25 and an overall increase of 13.4 percentage points compared to those aged 26–34, as well as an increased likelihood that patients aged 19–25 with stage IIB-IIIC colorectal cancer receive timely adjuvant chemotherapy compared to those aged 27–34.[239]

Two 2018 JAMA studies found the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) was associated with increased post-discharge mortality for patients hospitalized for heart failure and pneumonia.[270][271][272] A 2019 JAMA study found that ACA decreased emergency department and hospital use by uninsured individuals.[273] Several studies have indicated that increased 30-day, 90-day, and 1-year post-discharge mortality of heart failure patients can be attributed to "gaming the system" through inappropriate triage systems in emergency departments, use of observation stays when admissions are warranted, and delay of readmission beyond the 30th day post-discharge, strategies that can reduce readmission rates at the expense of quality of care and patient survival.[274] The HRRP was also shown to disproportionately penalize safety-net hospitals that predominately serve low-income patients.[275] A 2020 study by Treasury Department economists in the Quarterly Journal of Economics using a randomized controlled trial (the IRS sent letters to some taxpayers noting that they had paid a fine for not signing up for health insurance but not to other taxpayers) found that over two years, obtaining health insurance reduced mortality by 12 percent.[276][277] The study concluded that the letters, sent to 3.9 million people, may have saved 700 lives.[276]

A 2020 JAMA study found that Medicare expansion under the ACA was associated with reduced incidence of advanced-stage breast cancer, indicating that Medicaid accessibility led to early detection of breast cancer and higher survival rates.[278] Recent studies have also attributed to Medicaid expansion an increase in use of smoking cessation medications, cervical cancer screening, and colonoscopy, as well as an increase in the percentage of early-stage diagnosis of all cancers and the rate of cancer surgery for low-income patients.[279][280] These studies include a 2.1% increase in the probability of smoking cessation in Medicaid expansion states compared to non-expansion states, a 24% increase in smoking cessation medication use due to increased Medicaid-financed smoking cessation prescriptions, a 27.7% increase in the rate of colorectal cancer screening in Kentucky following Medicaid expansion with an accompanying improvement in colorectal cancer survival, and a 3.4% increase in cancer incidence following Medicaid expansion that was attributed to an increase in early-stage diagnoses.[279]

Transition-of-care interventions and Alternative Payment Models under the ACA have also shown promise in improving health outcomes.[281][282] Post-discharge provider appointment and telephone follow-up interventions have been shown to reduce 30-day readmission rates among general medical-surgical inpatients.[281] Reductions in 60, 90, and 180 post-discharge day readmission rates due to transition-of-care interventions have also been demonstrated, and a reduction in 30-day mortality has been suggested.[281] Total joint arthroplasty bundles as part of the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative have been shown to reduce discharge to inpatient rehabilitation facilities and post-acute care facilities, decrease hospital length of stay by 18% without sacrificing quality of care, and reduce the rate of total joint arthroplasty readmissions, half of which were due to surgical complications.[282] The Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program in Medicaid has also shown the potential to improve health outcomes, with early studies reporting positive and significant effects on total patient experience score, 30-day readmission rates, incidences of pneumonia and pressure ulcers, and 30-day mortality rates for pneumonia.[283] The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) payment and care model, a team-based approach to population health management that risk-stratifies patients and provides focused care management and outreach to high-risk patients, has been shown to improve diabetes outcomes.[284] A widespread PCMH demonstration program focusing on diabetes, known as the Chronic Care Initiative in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, found statistically significant improvements in A1C testing, LDL-C testing, nephropathy screening and monitoring, and eye examinations, with an accompanying reduction in all-cause emergency department visits, ambulatory care-sensitive emergency department visits, ambulatory visits to specialists, and a higher rate of ambulatory visits to primary care providers.[284] The ACA overall has improved coverage and care of diabetes, with a significant portion of the 3.5 million uninsured US adults aged 18–64 with diabetes in 2009-10 likely gaining coverage and benefits such as closure of the Medicaid Part D coverage gap for insulin.[285] 2.3 million of the approximately 4.6 million people aged 18–64 with undiagnosed diabetes in 2009–2010 may also have gained access to zero-cost preventative care due to section 2713 of the ACA, which prohibits cost sharing for United States Preventive Services Taskforce grade A or B recommended services, such as diabetes screenings.[285]

Distributional impact

In March 2018, the CBO reported that ACA had reduced income inequality in 2014, saying the law led the lowest and second quintiles (the bottom 40%) to receive an average of an additional $690 and $560 respectively while causing households in the top 1% to pay an additional $21,000 due mostly to the net investment income tax and the additional Medicare tax. The law placed relatively little burden on households in the top quintile (top 20%) outside of the top 1%.[10]

Federal deficit

CBO estimates of revenue and impact on deficit

The CBO reported in multiple studies that ACA would reduce the deficit, and repealing it would increase the deficit, primarily because of the elimination of Medicare reimbursement cuts.[8][9] The 2011 comprehensive CBO estimate projected a net deficit reduction of more than $200 billion during the 2012–2021 period:[9][286] it calculated the law would result in $604 billion in total outlays offset by $813 billion in total receipts, resulting in a $210 billion net deficit reduction.[9] The CBO separately predicted that while most of the spending provisions do not begin until 2014,[287][288] revenue would exceed spending in those subsequent years.[289][dead link] The CBO claimed the bill would "substantially reduce the growth of Medicare's payment rates for most services; impose an excise tax on insurance plans with relatively high premiums; and make various other changes to the federal tax code, Medicare, Medicaid, and other programs"[290]—ultimately extending the solvency of the Medicare trust fund by eight years.[291]

This estimate was made prior to the Supreme Court's ruling that enabled states to opt out of the Medicaid expansion, thereby forgoing the related federal funding. The CBO and JCT subsequently updated the budget projection, estimating the impact of the ruling would reduce the cost estimate of the insurance coverage provisions by $84 billion.[292][293][294]

The CBO in June 2015 forecast that repeal of ACA would increase the deficit between $137 billion and $353 billion over the 2016–2025 period, depending on the impact of macroeconomic feedback effects. The CBO also forecast that repeal of ACA would likely cause an increase in GDP by an average of 0.7% in the period from 2021 to 2025, mainly by boosting the supply of labor.[8]

Although the CBO generally does not provide cost estimates beyond the 10-year budget projection period because of the degree of uncertainty involved in the projection, it decided to do so in this case at the request of lawmakers, and estimated a second decade deficit reduction of $1.2 trillion.[290][295] CBO predicted deficit reduction around a broad range of one-half percent of GDP over the 2020s while cautioning that "a wide range of changes could occur".[296]

In 2017 CBO estimated that repealing the individual mandate alone would reduce the 10-year deficit by $338 billion.[297]

Opinions on CBO projections

The CBO cost estimates were criticized because they excluded the effects of potential legislation that would increase Medicare payments by more than $200 billion from 2010 to 2019.[298][299][300] However, the so-called "doc fix" is a separate issue that would have existed with or without ACA.[301][302][303] The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities objected that Congress had a good record of implementing Medicare savings. According to their study, Congress followed through on the implementation of the vast majority of provisions enacted in the past 20 years to produce Medicare savings, although not the doc fix.[304][305] The doc fix became obsolete in 2015 when the savings provision was eliminated, permanently removing that spending restraint.[306]

Health economist Uwe Reinhardt, wrote, "The rigid, artificial rules under which the Congressional Budget Office must score proposed legislation unfortunately cannot produce the best unbiased forecasts of the likely fiscal impact of any legislation."[307] Douglas Holtz-Eakin alleged that the bill would increase the deficit by $562 billion because, he argued, it front-loaded revenue and back-loaded benefits.[308]

Scheiber and Cohn rejected critical assessments of the law's deficit impact, arguing that predictions were biased towards underestimating deficit reduction. They noted, for example, it is easier to account for the cost of definite levels of subsidies to specified numbers of people than to account for savings from preventive healthcare, and that the CBO had a track record of overestimating costs and underestimating savings of health legislation;[309][310] stating, "innovations in the delivery of medical care, like greater use of electronic medical records[311] and financial incentives for more coordination of care among doctors, would produce substantial savings while also slowing the relentless climb of medical expenses ... But the CBO would not consider such savings in its calculations, because the innovations hadn't really been tried on such large scale or in concert with one another—and that meant there wasn't much hard data to prove the savings would materialize."[309]

In 2010 David Walker said the CBO estimates were not likely to be accurate, because they were based on the assumption that the law would not change.[312]

Employer mandate and part-time work

The employer mandate applies to employers of more than fifty where health insurance is provided only to the full-time workers.[313] Critics claimed it created a perverse incentive to hire part-timers instead.[314][315] However, between March 2010 and 2014, the number of part-time jobs declined by 230,000 while the number of full-time jobs increased by two million.[316][317] In the public sector full-time jobs turned into part-time jobs much more than in the private sector.[316][318] A 2016 study found only limited evidence that ACA had increased part-time employment.[319]

Several businesses and the state of Virginia added a 29-hour-a-week cap for their part-time employees,[320][unreliable source?][321][unreliable source?] to reflect the 30-hour-or-more definition for full-time worker.[313] As of 2013, few companies had shifted their workforce towards more part-time hours (4% in a survey from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis).[315] Trends in working hours[322] and the recovery from the Great Recession correlate with the shift from part-time to full-time work.[323][324] Other confounding impacts include that health insurance helps attract and retain employees, increases productivity and reduces absenteeism; and lowers corresponding training and administration costs from a smaller, more stable workforce.[315][322][325] Relatively few firms employ over 50 employees[315] and more than 90% of them already offered insurance.[326]

Most policy analysts (both right and left) were critical of the employer mandate provision.[314][326] They argued that the perverse incentives regarding part-time hours, even if they did not change existing plans, were real and harmful;[327][328] that the raised marginal cost of the 50th worker for businesses could limit companies' growth;[329] that the costs of reporting and administration were not worth the costs of maintaining employer plans;[327][328] and noted that the employer mandate was not essential to maintain adequate risk pools.[330][331] The provision generated vocal opposition from business interests and some unions who were not granted exemptions.[328][332]

Hospitals

From the start of 2010 to November 2014, 43 hospitals in rural areas closed. Critics claimed the new law had caused these closures. Many rural hospitals were built using funds from the 1946 Hill–Burton Act. Some of these hospitals reopened as other medical facilities, but only a small number operated emergency rooms (ER) or urgent care centers.[333]