| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Mount Behistun, Kermanshah Province, Iran |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii |

| Reference | 1222 |

| Inscription | 2006 (30th Session) |

| Area | 187 ha |

| Buffer zone | 361 ha |

| Coordinates | 34°23′26″N 47°26′9″E / 34.39056°N 47.43583°E |

The Behistun Inscription (also Bisotun, Bisitun or Bisutun; Persian: بیستون, Old Persian: Bagastana, meaning "the place of god") is a multilingual Achaemenid royal inscription and large rock relief on a cliff at Mount Behistun in the Kermanshah Province of Iran, near the city of Kermanshah in western Iran, established by Darius the Great (r. 522–486 BC).[1] It was important to the decipherment of cuneiform, as it is the longest known trilingual cuneiform inscription, written in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (a variety of Akkadian).[2]

Authored by Darius the Great sometime between his coronation as king of the Persian Empire in the summer of 522 BC and his death in autumn of 486 BC, the inscription begins with a brief autobiography of Darius, including his ancestry and lineage. Later in the inscription, Darius provides a lengthy sequence of events following the death of Cambyses II in which he fought nineteen battles in a period of one year (ending in December 521 BC) to put down multiple rebellions throughout the Persian Empire. The inscription states in detail that the rebellions were orchestrated by several impostors and their co-conspirators in various cities throughout the empire, each of whom falsely proclaimed himself king during the upheaval following Cambyses II's death. Darius the Great proclaimed himself victorious in all battles during the period of upheaval, attributing his success to the "grace of Ahura Mazda".

The inscription is approximately 15 m (49 ft) high by 25 m (82 ft) wide and 100 m (330 ft) up a limestone cliff from an ancient road connecting the capitals of Babylonia and Media (Babylon and Ecbatana, respectively). The Old Persian text contains 414 lines in five columns; the Elamite text includes 260 lines in eight columns, and the Babylonian text is in 112 lines.[3][4] A copy of the text in Aramaic, written during the reign of Darius II, was found in Egypt.[5] The inscription was illustrated by a life-sized bas-relief of Darius I, the Great, holding a bow as a sign of kingship, with his left foot on the chest of a figure lying supine before him. The supine figure is reputed to be the pretender Gaumata. Darius is attended to the left by two servants, and nine one-meter figures stand to the right, with hands tied and rope around their necks, representing conquered peoples. A Faravahar floats above, giving its blessing to the king. One figure appears to have been added after the others were completed, as was Darius's beard, which is a separate block of stone attached with iron pins and lead.

Name

[edit]The name Behistun is derived from usage in Ancient Greek and Arabic sources, particularly Diodorus Siculus and Ya'qubi, transliterated into English in the 19th century by Henry Rawlinson. The modern Persian version name is Bisotun.[6]

History

[edit]After the fall of the Persian Empire's Achaemenid Dynasty and its successors, and the lapse of Old Persian cuneiform writing into disuse, the nature of the inscription was forgotten, and fanciful explanations became the norm.

In 1598, Englishman Robert Sherley saw the inscription during a diplomatic mission to Safavid Persia on behalf of Austria, and brought it to the attention of Western European scholars. His party incorrectly came to the conclusion that it was Christian in origin.[7] French General Gardanne thought it showed "Christ and his twelve apostles", and Sir Robert Ker Porter thought it represented the Lost Tribes of Israel and Shalmaneser of Assyria.[8] In 1604, Italian explorer Pietro della Valle visited the inscription and made preliminary drawings of the monument.[9]

Translation efforts

[edit]

German surveyor Carsten Niebuhr visited in around 1764 for Frederick V of Denmark, publishing a copy of the inscription in the account of his journeys in 1778.[10] Niebuhr's transcriptions were used by Georg Friedrich Grotefend and others in their efforts to decipher the Old Persian cuneiform script. Grotefend had deciphered ten of the 37 symbols of Old Persian by 1802, after realizing that unlike the Semitic cuneiform scripts, Old Persian text is alphabetic and each word is separated by a vertical slanted symbol.[11]

In 1835, Sir Henry Rawlinson, an officer of the British East India Company army assigned to the forces of the Shah of Iran, began studying the inscription in earnest. As the town of Bisotun's name was anglicized as "Behistun" at this time, the monument became known as the "Behistun Inscription". Despite its relative inaccessibility, Rawlinson was able to scale the cliff with the help of a local boy and copy the Old Persian inscription. The Elamite was across a chasm, and the Babylonian four meters above; both were beyond easy reach and were left for later. In 1847, he was able to send a full and accurate copy to Europe.[12]

Later research and activity

[edit]

The site was visited by the American linguist A. V. Williams Jackson in 1903.[13] Later expeditions, in 1904 sponsored by the British Museum and led by Leonard William King and Reginald Campbell Thompson and in 1948 by George G. Cameron of the University of Michigan, obtained photographs, casts and more accurate transcriptions of the texts, including passages that were not copied by Rawlinson.[14][15][16][17] It also became apparent that rainwater had dissolved some areas of the limestone in which the text was inscribed, while leaving new deposits of limestone over other areas, covering the text.

In 1938, the inscription became of interest to the Nazi German think tank Ahnenerbe, although research plans were cancelled due to the onset of World War II.

The monument later suffered some damage from Allied soldiers using it for target practice in World War II, and during the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran.[18]

In 1999, Iranian archeologists began the documentation and assessment of damages to the site incurred during the 20th century. Malieh Mehdiabadi, who was project manager for the effort, described a photogrammetric process by which two-dimensional photos were taken of the inscriptions using two cameras and later transmuted into 3-D images.[19]

In recent years, Iranian archaeologists have been undertaking conservation works. The site became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006.[20]

In 2012, the Bisotun Cultural Heritage Center organized an international effort to re-examine the inscription.[21]

Content

[edit]

Lineage

[edit]In the first section of the inscription, Darius the Great declares his ancestry and lineage:

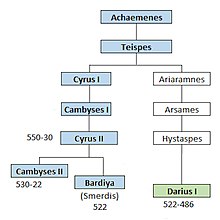

King Darius says: My father is Hystaspes [Vištâspa]; the father of Hystaspes was Arsames [Aršâma]; the father of Arsames was Ariaramnes [Ariyâramna]; the father of Ariaramnes was Teispes [Cišpiš]; the father of Teispes was Achaemenes [Haxâmaniš]. King Darius says: That is why we are called Achaemenids; from antiquity we have been noble; from antiquity has our dynasty been royal. King Darius says: Eight of my dynasty were kings before me; I am the ninth. Nine in succession we have been kings.

King Darius says: By the grace of Ahuramazda am I king; Ahuramazda has granted me the kingdom.

Territories

[edit]

Darius also lists the territories under his rule:

King Darius says: These are the countries which are subject unto me, and by the grace of Ahuramazda I became king of them: Persia [Pârsa], Elam [Ûvja], Babylonia [Bâbiruš], Assyria [Athurâ], Arabia [Arabâya], Egypt [Mudrâya], the countries by the Sea [Tyaiy Drayahyâ (Phoenicia)], Lydia [Sparda], the Greeks [Yauna (Ionia)], Media [Mâda], Armenia [Armina], Cappadocia [Katpatuka], Parthia [Parthava], Drangiana [Zraka], Aria [Haraiva], Chorasmia [Uvârazmîy], Bactria [Bâxtriš], Sogdia [Suguda], Gandhara [Gadâra], Scythia [Saka], Sattagydia [Thataguš], Arachosia [Harauvatiš] and Maka [Maka]; twenty-three lands in all.

Conflicts and revolts

[edit]Later in the inscription, Darius provides an eye-witness account of battles he successfully fought over a one-year period to put down rebellions which had resulted from the deaths of Cyrus the Great, and his son Cambyses II:

-

Relief of Nidintu-Bêl: "This is Nidintu-Bêl. He lied, saying "I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus. I am king of Babylon.""[22]

-

Relief of Tritantaechmes: "This is Tritantaechmes. He lied, saying "I am king of Sagartia, from the family of Cyaxares.""[22]

-

Relief of Arakha: "This is Arakha. He lied, saying: "I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus. I am king in Babylon.""[22]

Other historical monuments in the Behistun complex

[edit]The site covers an area of 116 hectares. Archeological evidence indicates that this region became a human shelter 40,000 years ago. There are 18 historical monuments other than the inscription of Darius the Great in the Behistun complex that have been registered in the Iranian national list of historical sites. Some of them are:

|

|

|

-

Statue of Herakles in Behistun complex

-

Herakles at Behistun, sculpted for a Seleucis Governor in 148 BC.

-

Bas relief of Mithridates II of Parthia and bas relief of Gotarzes II of Parthia and Sheikh Ali khan Zangeneh text endowment

-

Damaged equestrian relief of Gotarzes II at Behistun

-

Vologases's relief in Behistun

Similar reliefs and inspiration

[edit]

The Anubanini rock relief, also called Sarpol-i Zohab, of the Lullubi king Anubanini, dated to c. 2300 BC, and which is located not far from the Behistun reliefs at Sarpol-e Zahab, is very similar to the reliefs at Behistun. The attitude of the ruler, the trampling of an enemy, the lines of prisoners are all very similar, to such extent that it was said that the sculptors of the Behistun Inscription had probably seen the Anubanini relief beforehand and were inspired by it.[23] The Lullubian reliefs were the model for the Behistun reliefs of Darius the Great.[24]

The inscriptional tradition of the Achaemenids, starting especially with Darius I, is thought to have derived from the traditions of Elam, Lullubi, the Babylonians and the Assyrians.[25]

See also

[edit]- Behistun palace

- Darius I of Persia

- Achaemenid empire

- Taq-e Bostan (Rock reliefs of various Sassanid kings)

- Pasargadae (Tomb of Pasargadae Cyrus the Great)

- Shapur I's inscription at the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht

- Naqsh-e Rajab

- Cities of the Ancient Near East

- Gaumata (False Smerdis)

- Anubanini rock relief

- List of colossal sculptures in situ

- World Heritage Sites by country

Notes

[edit]- ^ "The Arya in Iran".

- ^ "Behistun Inscription is a cuneiform text in three ancient languages."Bramwell, Neil D. (1932). Ancient Persia. NJ Berkeley Heights. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7660-5251-2.

- ^ Tavernier, Jan (2021). "A list of the Achaemenid Royal Inscriptions by language". Phoenix (in French). 67 (2): 1–4. ISSN 0031-8329. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

The rock inscription itself contains no less than 414 lines of Old Persian, 112 lines of Babylonian and 260 lines of Elamite (in an older and a younger version).

- ^ "The Bīsitūn Inscription [CDLI Wiki]". cdli.ox.ac.uk. 2015-09-06. Archived from the original on 2023-03-25. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

This tri-lingual inscription has 414 lines in Old Persian cuneiform, 260 in Elamite cuneiform, and 112 in Akkadian cuneiform (Bae: 2008)

- ^ Tavernier, Jan, "An Achaemenid Royal Inscription: The Text of Paragraph 13 of the Aramaic Version of the Bisitun Inscription", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 161–76, 2001

- ^ King, L.W.; Thompson, R.C.; Budge, E.A.W. (1907). The Sculptures and Inscription of Darius the Great: On the Rock of Behistûn in Persia. British museum. p. xi.

The name of the Rock is derived from that of the small village of Bîsitûn or Bîsutûn, which lies near its foot. The form of the name "Behistûn" is not used by the modern inhabitants of the country, although it is that by which the Rock is best known among European scholars. The name "Behistûn," more correctly "Bahistûn," was borrowed by the late Major-General Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, Bart., G.C. B., from the Arabic geographer Yakût, who mentions the village and its spring, and describes the Rock as being of great height, and refers to the sculptures upon it. The earliest known name of the Rock is that given by Diodorus Siculus, who calls it τό Βαγίστανον ορος, whence, no doubt, are derived the modern forms of the name.

- ^ E. Denison Ross, The Broadway Travellers: Sir Anthony Sherley and his Persian Adventure, Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0-415-34486-7

- ^ [1] Robert Ker Porter, Travels in Georgia, Persia, Armenia, ancient Babylonia, &c. &c. : during the years 1817, 1818, 1819, and 1820, volume 2, Longman, 1821

- ^ Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2013). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. Springer US. ISBN 9781475751338.

- ^ Carsten Niebuhr, Reisebeschreibung von Arabien und anderen umliegenden Ländern, 2 volumes, 1774 and 1778

- ^ "Old Persian". Ancient Scripts. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ Harari, Y.N. (2015). "15. The Marriage of Science and Empire". Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-231610-3.

- ^ A. V. Williams Jackson, "The Great Behistun Rock and Some Results of a Re-Examination of the Old Persian Inscriptions on It", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 24, pp. 77–95, 1903

- ^ [2] W. King and R. C. Thompson, The sculptures and inscription of Darius the Great on the Rock of Behistûn in Persia: a new collation of the Persian, Susian and Babylonian texts, Longmans, 1907

- ^ George G. Cameron, The Old Persian Text of the Bisitun Inscription, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 47–54, 1951

- ^ George G. Cameron, The Elamite Version of the Bisitun Inscriptions, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 59–68, 1960

- ^ W. C. Benedict and Elizabeth von Voigtlander, Darius' Bisitun Inscription, Babylonian Version, Lines 1–29, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 1956

- ^ "BEHISTUN Inscription - Persia". Archived from the original on 2012-02-03. Retrieved 2011-07-20.

- ^ "Documentation of Behistun Inscription Nearly Complete". Chnpress.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-18. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ "Iran's Bisotoon Historical Site Registered in World Heritage List". Payvand.com. 2006-07-13. Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ "Intl. Experts to reread Bisotun inscriptions - Tehran Times". Archived from the original on 2012-05-29. Retrieved 2012-04-14. Intl. experts to reread Bisotun inscriptions, Tehran Times, May 27, 2012[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f Behistun, minor inscriptions DBb inscription- Livius. Archived from the original on 2020-03-10. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ^ Potts, D. T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 318. ISBN 9780521564960. Archived from the original on 2017-10-12. Retrieved 2019-03-15.

- ^ Wiesehofer, Josef (2001). Ancient Persia. I.B.Tauris. p. 13. ISBN 9781860646751. Archived from the original on 2012-05-02. Retrieved 2019-03-17.

- ^ Eastmond, Antony (2015). Viewing Inscriptions in the Late Antique and Medieval World. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9781107092419. Archived from the original on 2020-05-18. Retrieved 2019-03-16.

References

[edit]- Adkins, Lesley, Empires of the Plain: Henry Rawlinson and the Lost Languages of Babylon, St. Martin's Press, New York, 2003.

- Blakesley, J. W. An Attempt at an Outline of the Early Medo-Persian History, founded on the Rock-Inscriptions of Behistun taken in combination with the Accounts of Herodotus and Ctesias. (Trinity College, Cambridge,) in the Proceedings of the Philological Society.

- Borger, Rykle. Die Chronologie des Darius-Denkmals am Behistun-Felse, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 1982, ISBN 3-525-85116-2.

- Cameron, George G. "Darius Carved History on Ageless Rock". National Geographic Magazine. Vol. XCVIII, Num. 6, December 1950. (pp. 825–844)

- Thompson, R. Campbell. "The Rock of Behistun". Wonders of the Past. Edited by Sir J. A. Hammerton. Vol. II. New York: Wise and Co., 1937. (pp. 760–767) "Behistun". Members.ozemail.com.au. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- Louis H. Gray, Notes on the Old Persian Inscriptions of Behistun, Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 23, pp. 56–64, 1902

- Paul J. Kosmin, A New Hypothesis: The Behistun Inscription as Imperial Calendar, Iran - Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies, August 2018

- A. T. Olmstead, Darius and His Behistun Inscription, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 392–416, 1938

- Rawlinson, H.C., Archaeologia, 1853, vol. xxxiv, p. 74.

- Rubio, Gonzalo. "Writing in another tongue: Alloglottography in the Ancient Near East". In Margins of Writing, Origins of Cultures (ed. Seth Sanders. 2nd printing with postscripts and corrections. Oriental Institute Seminars, 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), pp. 33–70."Oriental Institute | Oriental Institute Seminars (OIS)". Oi.uchicago.edu. 2009-06-18. Archived from the original on 2014-06-04. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- Saber Amiri Parian, A New Edition of the Elamite Version of the Behistun Inscription (I), Cuneiform Digital Library Bulletin 2017:003.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. Die altpersischen Inschriften der Achaimeniden. Editio minor mit deutscher Übersetzung, Reichert, Wiesbaden, 2023, ISBN 978-3-7520-0716-9, pp. 9 and 36–96.

External links

[edit]- King, L. W.; Thompson, R. Campbell (1907). The sculptures and inscription of Darius the Great on the Rock of Behistûn in Persia : a new collation of the Persian, Susian and Babylonian texts, with English translations, etc. British Museum.

- The Behistun Inscription Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, livius.org article by Jona Lendering, including Persian text (in cuneiform and transliteration), King and Thompson's English translation, and additional materials

- Tolman, Herbert Cushing (1908). The Behistan inscription of King Darius: translation and critical notes to the Persian text with special reference to recent re-examinations of the rock. Vanderbilt University.

- Brief description of Bisotun from UNESCO

- "Bisotun receives its World Heritage certificate", Cultural Heritage News Agency, Tehran, July 3, 2008

- Other monuments of Behistun Archived 2016-11-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Rüdiger Schmitt, "Bisotun i", Encyclopaedia Iranica [3]

- Hyland, John O. (2014). "The Casualty Figures in Darius' Bisitun Inscription". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History. 1 (2): 173–199. doi:10.1515/janeh-2013-0001. S2CID 180763595.

| History | ||

|---|---|---|

| Art | ||

| Architecture | ||

| Culture | ||

| Warfare |

| |

| Diplomacy | ||

| Administration | ||

| Dynasties | ||

| Related | ||

| Cultural |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Natural | ||

Kermanshah Province, Iran | ||

|---|---|---|

| Capital | ||

| Counties and cities | ||

| Sights |

| |

| populated places | ||

![Relief of ššina c. 519 BC: "This is ššina. He lied, saying "I am king of Elam.""[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3f/Behistun_Relief%2C_Assina.jpg/96px-Behistun_Relief%2C_Assina.jpg)

![Relief of Nidintu-Bêl: "This is Nidintu-Bêl. He lied, saying "I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus. I am king of Babylon.""[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/Behistun_Relief_Nidintu-B%C3%AAl.jpg/120px-Behistun_Relief_Nidintu-B%C3%AAl.jpg)

![Relief of Tritantaechmes: "This is Tritantaechmes. He lied, saying "I am king of Sagartia, from the family of Cyaxares.""[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/Behistun_Relief%2C_Tritantaechmes.jpg/120px-Behistun_Relief%2C_Tritantaechmes.jpg)

![Relief of Arakha: "This is Arakha. He lied, saying: "I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus. I am king in Babylon.""[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/07/Behistun_relief_Arakha.jpg/120px-Behistun_relief_Arakha.jpg)

![Relief of Frâda: "This is Frâda. He lied, saying "I am king of Margiana.""[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Behistun_relief_Frada.jpg/75px-Behistun_relief_Frada.jpg)

![Behistun relief of Skunkha. Label: "This is Skunkha the Sacan."[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c6/Behistun_relief_Skunkha.jpg/60px-Behistun_relief_Skunkha.jpg)