Bob Rafelson | |

|---|---|

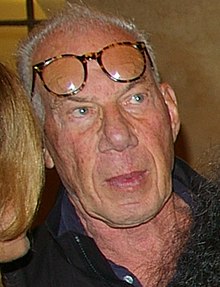

Rafelson in 2009 | |

| Born | Robert Rafelson February 21, 1933 New York City, U.S |

| Died | July 23, 2022 (aged 89) Aspen, Colorado, U.S. |

| Education | Dartmouth College |

| Occupation(s) | Film director, producer, screenwriter |

| Years active | 1959–2002 |

| Spouses | Toby Carr

(m. 1955; div. 1977)Gabrielle Taurek (m. 1999) |

| Children | 4 |

Robert Jay Rafelson (February 21, 1933 – July 23, 2022) was an American film director, writer and producer. He is regarded as one of the key figures in the founding of the New Hollywood movement of the 1970s. Among his best-known films as a director include those made as part of the company he co-founded, Raybert/BBS Productions, Five Easy Pieces (1970) and The King of Marvin Gardens (1972) as well as acclaimed later films, The Postman Always Rings Twice (1981) and Mountains of the Moon (1990). Other films he produced as part of BBS include two of the most significant films of the era, Easy Rider (1969) and The Last Picture Show (1971). Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces and The Last Picture Show were all chosen for inclusion in the Library of Congress' National Film Registry. He was also one of the creators of the pop group and TV series The Monkees with BBS partner Bert Schneider. His first wife was the production designer Toby Carr Rafelson.

Robert Jay Rafelson was born in Manhattan on February 21, 1933[1] to a Jewish family,[2] the son of Marjorie (Blumenfeld) and Sydney Rafelson, a hat ribbon manufacturer.[3] His much-older first cousin, once removed, was screenwriter and playwright Samson Raphaelson, the author of The Jazz Singer, who wrote nine films for director Ernst Lubitsch.[4] "Samson took an interest in my work," Rafelson told critic David Thomson. "If he liked a picture, then I was his favorite nephew. But if he didn't like it, I was a distant cousin!"[5]

Rafelson attended the Trinity-Pawling School, a boarding school in Pawling, New York, from which he graduated in 1950. As a teenager he would often run away from home to pursue an adventurous lifestyle, including riding in a rodeo in Arizona and playing in a jazz band in Acapulco. After studying philosophy at Dartmouth College (where he had made friends with screenwriter Buck Henry),[6] and graduating in 1954, Rafelson was drafted into the U.S. Army and stationed in Japan. In Japan he worked as a disk jockey, translated Japanese films and was an adviser to the Shochiku Film Company as to what films would be financially successful in the United States.[7] In an interview with critic Peter Tonguette, Rafelson said he was fascinated by the films he saw in Japan, especially those of Yasujirō Ozu, whose original approach to editing captivated him as a young man: "I'd have to watch an Ozu movie over and over again—say, Tokyo Story—and I was hypnotized by the stillness of his frames, his sureness of composition," he said. "So I suppose my own aesthetic evolved from looking at certain kinds of pictures—Bergman and Ozu and John Ford, if you will."[8]

Rafelson began dating Toby Carr in high school and they later married in the mid-1950s. The couple had two children: Peter Rafelson, born in 1960, and Julie Rafelson, born in 1962.[9] Toby Rafelson was a production designer on many films, including her husband's Five Easy Pieces, The King of Marvin Gardens, and Stay Hungry, as well as Martin Scorsese's Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore and Jonathan Demme's Melvin and Howard.[10][better source needed]

Rafelson's first professional job was as a story editor on the TV series Play of the Week for producer David Susskind in 1959. The series produced televised stage plays from contemporary and classical authors. Rafelson's job required him to read hundreds of plays, select which were to be produced, and write some additional dialogue uncredited. Rafelson's first writing credits were for an episode of the TV series The Witness in 1960 and an episode of the series The Greatest Show on Earth in 1963.[7]

In June 1962, Rafelson and his family moved to Hollywood, where he began working as an associate producer on television shows and films at Universal Pictures, Revue Productions, Desilu Productions and Screen Gems.[6] After an argument with Lew Wasserman over creative differences on the show Channing, culminating in Rafelson sweeping "awards, medallions, souvenir ashtrays, and other tchotchkes" from Wasserman's desk, he was fired.[11]

In 1965, while working at Screen Gems, Rafelson met fellow producer Bert Schneider. They became fast friends and created the company Raybert Productions together that year. Raybert would later become BBS Productions and produce films as a subsidiary of Columbia Pictures.[7] Rafelson and Schneider's first project was a television series about a rock 'n' roll group.[12] Rafelson said that the idea for the show, which was inspired by his own misadventures while playing in a band in Mexico, predated A Hard Day's Night. Rafelson said, "I had conceived the show before The Beatles existed," and it was based on his time as an itinerant musician more "interested in having fun" than "in earning a living."[8] Raybert Productions sold the idea to Screen Gems and, when they were unable to get either the Dave Clark Five or the Lovin' Spoonful for the show, ran ads in Daily Variety and The Hollywood Reporter for musicians. The band that they created was The Monkees and the series ran from 1966 until 1968.[7]

The Monkees was immediately a success with audiences and, despite the band being a manufactured act, was particularly popular with the youth demographic at the time.[7] Rafelson and Schneider won the Emmy Award for Outstanding Comedy Series as producers in 1967.[13] Rafelson has said that "the whole show was created in effect in the editing room. The tempo was of paramount importance...I had to direct one or two of the shows for television to set the pattern of how these things should be made." Rafelson had said that "of the first 32 shows, 29 were directed by people who had never directed before, including me. So the idea of using new directors not perhaps too encumbered by traditional ways of thinking was initiated on that series and just continued on the movies we made later."[7] He has cited the series' "radically different way of cutting and doing a half hour comedy because there were interviews that were interspersed [and] there was documentary footage."[8]

Rafelson and Bert Schneider's newfound success allowed them to get more funding for Raybert Productions and to establish the record company Colgems. Their next project was Head, a feature film starring the Monkees. Co-written with friend Jack Nicholson, and featuring appearances by Nicholson, Victor Mature, Teri Garr, Carol Doda, Annette Funicello, Frank Zappa, Sonny Liston, Timothy Carey, Ray Nitschke, and Dennis Hopper, it was Rafelson's debut as a feature film director. Rafelson said, "Of course Head is an utterly and totally fragmented film. Among other reasons for making it was that I thought I would never get to make another movie, so I might as well make fifty to start out with and put them all in the same feature."[7]

Head represented the first of many Rafelson-Nicholson collaborations, later to include Five Easy Pieces, The King of Marvin Gardens and The Postman Always Rings Twice, among others. In a profile of Rafelson in Esquire magazine, Nicholson commented: "I may have thought I started his career, but I think he started my career."[14]

Head is a plotless, stream-of-consciousness film that, amongst other things, attempts to deconstruct the musical personas of the Monkees and satirize the consumer ideals of "image". In a song sung by the Monkees, they seem to confess by saying: Hey, hey, we are The Monkees/ You know we love to please/ A manufactured image/ With no philosophies. Other scenes utilize psychedelic or surrealistic theatrics such as the Monkees being sucked through a giant vacuum cleaner and turning into specks of dandruff in Victor Mature's head. The film ends with the Monkees being loaded into a truck and driven out of the Columbia Studio gates. The film was a financial failure and the popularity of the Monkees was already in decline,[7] but it has since emerged as a cult classic with a strong following.[citation needed]

Raybert's next project, Easy Rider, directed by Dennis Hopper, premiered at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival and was released in July 1969, quickly becoming a cultural phenomenon. The film's success gave Raybert enough funds and clout to pursue more ambitious projects. Rafelson and Schneider soon added Schneider's childhood friend Stephen Blauner to their company and its name became BBS Productions (Bert, Bob and Steve). BBS's first project, Five Easy Pieces, was Rafelson's second feature film, shot in 1969.[7] In an interview with Tonguette in Sight & Sound, Rafelson explained the idea behind BBS: "My thought was: there is so much talent here in the US but little talent for recognizing it. I thought together we could do this but that Bert should manage it."[15]

The New York Times critic Manohla Dargis has highlighted Rafelson and Schneider for founding "the groovy 1960s company Raybert (later known as BBS Productions) — and gave us Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces, The Last Picture Show and Hearts and Minds, and lamenting the absence of such risk-taking companies today."[16]

Five Easy Pieces was written by Rafelson and Carole Eastman (under the alias Adrien Joyce) and starred Nicholson, Karen Black, and Susan Anspach. Nicholson plays Bobby Dupea, a gifted classical piano player who works on an oil rig in California and spends most of his time drinking beer and bowling with his put-upon girlfriend Rayette (Black). Bobby is constantly dissatisfied and a non-conformist, stating: "I move around a lot. Not because I'm looking for anything really, but to get away from things that go bad if I stay."[7] Bobby learns from his sister that his father has had a stroke and decides to travel back to his family home in the San Juan Islands in Washington state. He and Rayette go on a road trip to Washington, picking up two hippie hitch-hikers along the way and in the film's most notorious highlight, Bobby unsuccessfully battles with a waitress in a diner for an omelet with wheat toast. The scene ends with a violent sweeping of Bobby's arm clearing the table. "Do you see this sign!?" he blurts. True, it is derivative of Brando's close to precise action in A Streetcar named Desire but Bobby may have been channeling, as a trope, someone's behavior he'd seen in the movies. (To cool a possible dim view of Rafelson's suggested plagiarism, in 1996 in Blood and Wine a cinematic debriefing occurs where Nicholson accompanied by Michael Caine, in seeking a clear table for them both in a cafeteria, effects it by picking up a tray containing used utensils from one table and drops it to the floor in nonchalant simplicity.) Rafelson described Bobby as "a guy who is out of touch with his emotions."[7]

The film was a financial hit, earning $18 million at the box office, was widely admired by the critics, and was nominated for four Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Actor (Nicholson), Best Supporting Actress (Black) and Best Original Screenplay. As a producer and co-writer of the film, Rafelson was nominated for two Oscars. It also received the New York Film Critics Award for Best Director and for Best Film of 1970. Film critic David Robinson called Rafelson "a new director who uses film with the subtlety of a novelist, but without losing any of the concentration and economy potential in the cinema's unique mixture of image and sound."[7]

In his original 1970 review in the Chicago Sun-Times, film critic Roger Ebert called Five Easy Pieces "a masterpiece of heartbreaking intensity", adding, "The movie is joyously alive to the road life of its hero. . . . Robert Eroica Dupea is one of the most unforgettable characters in American movies." And, in his "Great Movies" essay on the film, Ebert reflected on seeing the impact of having seen it for the first time: "We'd had a revelation. This was the direction American movies should take: Into idiosyncratic characters, into dialogue with an ear for the vulgar and the literate, into a plot free to surprise us about the characters, into an existential ending not required to be happy." Ebert later included Five Easy Pieces in his "Great Movies" series.[17]

Rafelson's next film was The King of Marvin Gardens, released in 1972 through BBS. The film was written by Jacob Brackman, from a story by Rafelson and Brackman, and starred Jack Nicholson, Bruce Dern, Ellen Burstyn, Julia Anne Robinson, Scatman Crothers and Charles Lavine. The title refers to the original Atlantic City version of the Monopoly game board, where the misspelled and misplaced "Marvin Gardens" was one of the Yellow squares in the children's game of capitalistic success.[citation needed]

In the film, Nicholson plays David Staebler, a melancholy Philadelphia disk jockey who tells long, angst-ridden stories of his childhood over the radio and lives with his elderly Grandfather (Lavine). David receives a call from his extroverted con artist brother Jason (Dern) asking him to bail him out of jail in Atlantic City. When David arrives he gets caught up in Jason's scheme to develop a South Pacific island into a gambling casino so that the brothers can "fulfill their childhood dream of an island kingdom of their own". David joins up with Jason, his girlfriend Sally (Burstyn) and Sally's stepdaughter Jessica (Robinson) to make the dream a reality. But David soon learns that Jason is in over his head and owes money to a real gangster named Lewis (Crothers), who is not amused with Jason's idealism.[citation needed]

The King of Marvin Gardens received mixed reviews and was not a financial success, although critics have since re-evaluated it. David Thomson wrote that it "may be an even better film" than Five Easy Pieces,[5] although it was the next-to-last film made by BBS. As Rafelson explained to Thomson, "I wanted to make my own pictures. And Bert was moving towards radical politics. He wanted to do Hearts and Minds [the 1974 documentary about the Vietnam war]."[5] Hearts and Minds (directed by Rafelson's friend of many decades, Peter Davis) won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature,[18] and was the last film to bear the BBS imprimatur[citation needed].

Rafelson then spent more than a year researching a film that would never be made about the slave trade in Africa. He traveled over five thousand miles in West Africa and has said that he "lived the life of many of the characters that I'd read about." Rafelson then "wanted to turn to something more cheerful, to project a more exhilarating aspect of myself."[7] His next film was Stay Hungry, based on the novel by Charles Gaines and adapted by Rafelson and Gaines, featuring Jeff Bridges, Sally Field, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Scatman Crothers.[19]

Bridges stars as Craig Blake, a millionaire in Alabama who has recently inherited his parents' fortune after their tragic deaths in a plane crash. He lives a lonely life in his mansion with only his butler (Crothers) to keep him company as he idles away his days. When he becomes involved in a shady investment firm, he visits the Olympic Spa gym, where bodybuilders are training for the upcoming Mr. Universe contest. He befriends bodybuilder Joe Santo (Schwarzenegger), who teaches him that "You can't grow without burning. I don't like to be too comfortable. Once you get used to it it's hard to give up. I like to stay hungry."[citation needed] He also begins dating the gym's receptionist Mary Tate (Field), but his upper-class friends do not approve of his new lower-class friends. In the end Blake chooses his new friends and buys the gym with Santo.[7] The film earned Rafelson and Gaines a nomination for Best Comedy Adapted from Another Medium from the Writers Guild of America,[citation needed] while Schwarzenegger received a Golden Globe for Best Acting Debut in a Motion Picture.[citation needed]

In 1978, Rafelson began production on the film Brubaker, starring Robert Redford, Yaphet Kotto, Jane Alexander and Morgan Freeman. He had spent several days at a top security prison to research the film. Rafelson was fired from the film after just ten days of shooting. "That's the time when I allegedly 'punched somebody out,'" Rafelson said. "He was the head of the studio, and there was a lot of talk about it—and by the way, it was grossly exaggerated."[20] He was replaced by Stuart Rosenberg.[7] Rafelson filed a breach-of-contract and slander lawsuit in May 1979 asking for damages of $10 million, claiming that 20th Century Fox had assured him that he would have complete autonomy and creative control and had made statements that implied that he was incompetent, emotionally unstable, and not qualified to direct a major motion picture.[21]

Rafelson again teamed up with Jack Nicholson in 1981, directing him in their fourth collaboration, The Postman Always Rings Twice, based on the novel by James M. Cain which had been adapted as a film in 1946 with John Garfield and Lana Turner. The remake was written by David Mamet — the first screenplay by the playwright — and co-starred Jessica Lange. Nicholson plays a Depression-era drifter who happens upon a rural diner and becomes involved with the owner's wife in a plot to kill her husband. Rafelson has said of the film's reception, "The critics in America—at least when it first came out, now they have switched – didn't like it very much, but in France and in Germany and in Russia and in places that I have traveled since the making of this movie, this seems to have emerged as one of the movies that they like most of mine because of its unlikely romantic nature."[8] In France, in particular, he is considered an auteur.[22]

In 1987, Rafelson directed Black Widow, starring Debra Winger and Theresa Russell, and written by Ronald Bass. The film received favorable reviews, with The Washington Post critic Paul Attanasio writing that "the joys of Black Widow are the joys of a film well made—the cinematography of Conrad Hall, the production design of Gene Callahan, and a fabulous cast," which also featured Dennis Hopper, Nicol Williamson, and Diane Ladd.[23] Rafelson's next project was Mountains of the Moon (1990), a film about the 1857–58 journey of Richard Francis Burton and John Hanning Speke in their expedition to central Africa — the project that culminated in Speke's discovery of the source of the Nile River. It starred Patrick Bergin as Burton and Iain Glen as Speke, and was hailed by Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert as "completely absorbing". Ebert continued: "It tells its story soberly and intelligently, and with quiet style... It's the kind of movie that sends you away from the screen filled with curiosity to know more about this man Burton."[24] In Newsweek, critic Jack Kroll wrote: "The exploits of Sir Richard Francis Burton make Lawrence of Arabia look like a tourist. . . . From scene to scene this film grips you as few movies do, moving between Africa and England to spotlight an extraordinary range of characters in both 'primitive' and 'civilized' cultures: from the African tribal chiefs, mild or murderous, to the nabobs of the Royal Geographical Society, honest or treacherous."[25] Rafelson later observed, "I was very lucky to make that movie. And I can tell you, if there was ever a movie that I enjoyed making, it was that one."[8]

Rafelson and Nicholson collaborated on film projects for almost 30 years. Rafelson again teamed up with Nicholson in 1992 for their fifth collaboration, and were joined by Five Easy Pieces screenwriter Carole Eastman, for the film Man Trouble. In 1996, he made his sixth and final with Nicholson, Blood and Wine. His last films were 1998's Poodle Springs and 2002's No Good Deed, based on works by Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, respectively. No Good Deed was entered into the 24th Moscow International Film Festival.[26]

Rafelson has been honored at numerous international film festivals, including in Argentina, Brazil, England, France, Greece, Japan, Serbia and Turkey, and has given many masterclasses.[citation needed] He contributed commentaries or interviews to the DVD or Blu-ray releases of Head, Five Easy Pieces, The King of Marvin Gardens, Stay Hungry, The Postman Always Rings Twice, and Blood and Wine. Rafelson has also contributed essays to the Los Angeles Times Magazine and John Brockman's collection The Greatest Inventions of the Past 2,000 Years.[citation needed]

Bob Rafelson married Toby Carr in 1955. They lived near Aspen, Colorado, in a house "built in the '50s by a climber and his 11-year-old son" that Rafelson bought in 1970. "We live here and nowhere else," he said.[27] Rafelson's 10-year-old daughter Julie died of injuries when a propane stove exploded in the Rafelsons' Aspen home in August 1973. Shortly after that Toby Rafelson was diagnosed with cancer, but eventually recovered.[28] While they later divorced, they remained close friends, and Rafelson referred to his first wife as his "head nurse, teacher, brujo."[8] His eldest son is songwriter Peter Rafelson, who wrote the song "Open Your Heart", which became a hit for Madonna.[29]

Rafelson married Gabrielle Taurek in 1999 and the couple had two sons, E.O. and Harper. He died from lung cancer at his home in Aspen on July 23, 2022, at the age of 89.[1][30][31]

| Year | Title | Director | Writer | Producer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Head | Yes | Yes | Yes | Co-written with Jack Nicholson |

| 1970 | Five Easy Pieces | Yes | Story | Yes | Story co-written with Adrien Joyce |

| 1972 | The King of Marvin Gardens | Yes | Story | Yes | Story co-written with Jacob Brackman |

| 1976 | Stay Hungry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Co-written with Charles Gaines |

| 1981 | The Postman Always Rings Twice | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Modesty | Yes | Yes | No | Short film[32] | |

| 1987 | Black Widow | Yes | No | No | |

| 1990 | Mountains of the Moon | Yes | Yes | No | Co-written with William Harrison |

| 1992 | Man Trouble | Yes | No | No | |

| 1994 | "Wet" | Yes | Yes | No | Short film later released in Tales of Erotica[33] |

| 1996 | Blood and Wine | Yes | Story | No | Story co-written with Nick Villiers |

| 2002 | No Good Deed | Yes | No | No | |

| Porn.com | Yes | Yes | No | Short film[34] |

As uncredited producer[31]

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Picture Windows | Episode: "Armed Response" (E6) |

| 1998 | Poodle Springs | Made-for-television film |