Ingmar Bergman | |

|---|---|

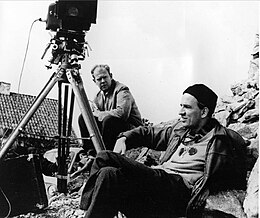

Bergman in 1966 | |

| Born | Ernst Ingmar Bergman 14 July 1918 Uppsala, Sweden |

| Died | 30 July 2007 (aged 89) Fårö, Sweden |

| Other names | Buntel Eriksson |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1944–2005 |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 9, including Linn, Eva, Mats, Anna and Daniel |

| Parent |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Signature | |

| |

Ernst Ingmar Bergman[a] (14 July 1918 – 30 July 2007) was a Swedish film and theatre director and screenwriter. Widely considered one of the greatest and most influential film directors of all time,[1][2][3] his films have been described as "profoundly personal meditations into the myriad struggles facing the psyche and the soul".[4] Some of his most acclaimed works include The Seventh Seal (1957), Wild Strawberries (1957), Persona (1966) and Fanny and Alexander (1982), which were included in the 2012 edition of Sight & Sound's Greatest Films of All Time.[5] He was also ranked No. 8 on the magazine's 2002 "Greatest Directors of All Time" list.[6]

Bergman directed more than 60 films and documentaries, most of which he also wrote, for both cinema releases and television screenings. Most of his films were set in Sweden, and many of his films from 1961 onward were filmed on the island of Fårö. He forged a creative partnership with his cinematographers Gunnar Fischer and Sven Nykvist. Bergman also had a theatrical career that included periods as Leading Director of Sweden's Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm and of Germany's Residenztheater in Munich.[7] He directed more than 170 plays. Among his company of actors were Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson, Liv Ullmann, Gunnar Björnstrand, Erland Josephson, Ingrid Thulin, Gunnel Lindblom and Max von Sydow.

Ernst Ingmar Bergman was born in Uppsala on 14 July 1918,[8] the son of nurse Karin (née Åkerblom) and Lutheran minister (and later chaplain to the King of Sweden) Erik Bergman. His mother was of Walloon descent.[9][10] The Bergman family was originally from Järvsö. On his father's side, Bergman was a descendant of the noble Bröms, Ehrenskiöld, and Stockenström clergy families of Finnish, German, and Swedish origin. His father also descended from the German noble families Flach and de Frese introduced at the Swedish Riddarhuset. Bergman's paternal grandmother and maternal grandfather were cousins, making his parents second cousins. On his mother's side, he was descended from Dutch merchant Paul Calwagen, who left Holland for Sweden in the 17th century; Paul's Dutch-Swedish wife, Maria van der Hagen, was a descendant of the court painter Laurens van der Plas. Bergman's mother was also a descendant of the noble Tigerschiöld and Weinholz families, as well as the Bure family.[11][12]

Bergman grew up with his older brother Dag and younger sister Margareta surrounded by religious imagery and discussion. His father was a conservative parish minister with strict ideas of parenting. Ingmar was locked up in dark closets for infractions such as wetting himself. "While father preached away in the pulpit and the congregation prayed, sang, or listened", Ingmar wrote in his autobiography Laterna Magica, "I devoted my interest to the church's mysterious world of low arches, thick walls, the smell of eternity, the coloured sunlight quivering above the strangest vegetation of medieval paintings and carved figures on ceilings and walls. There was everything that one's imagination could desire—angels, saints, dragons, prophets, devils, humans..." Although raised in a devout Lutheran household, Bergman later stated that he lost his faith at age eight, and came to terms with this fact while making Winter Light in 1962.[13] His interest in theatre and film began early; at the age of nine, he traded a set of tin soldiers for a magic lantern. Within a year, he had created a private world by playing with this toy in which he felt completely at home. He fashioned his own scenery, marionettes, and lighting effects and gave puppet productions of Strindberg plays in which he spoke all the parts."[14][15]

Bergman attended the Palmgren School as a teenager. His school years were unhappy,[16] and he remembered them unfavourably in later years. In a 1944 letter concerning the film Torment (sometimes known as Frenzy), which sparked debate on the condition of Swedish high schools (and which Bergman had written),[17] the school's principal Henning Håkanson wrote, among other things, that Bergman had been a "problem child".[18] Bergman wrote in a response that he had strongly disliked the emphasis on homework and testing in his formal schooling.

In 1934, aged 16, he was sent to Germany to spend the summer holidays with family friends. He attended a Nazi rally in Weimar at which he saw Adolf Hitler.[19] He later wrote in Laterna Magica (The Magic Lantern) about the visit to Germany, describing how the German family had put a portrait of Hitler on the wall by his bed, and that "for many years, I was on Hitler's side, delighted by his success and saddened by his defeats".[20] Bergman commented that "Hitler was unbelievably charismatic. He electrified the crowd. ... The Nazism I had seen seemed fun and youthful."[21] Bergman did two five-month stretches of mandatory military service in Sweden.[22] He later reflected, "When the doors to the concentration camps were thrown open ... I was suddenly ripped of my innocence."[21]

Bergman enrolled at Stockholm University College (later renamed Stockholm University) in 1937, to study art and literature. He spent most of his time involved in student theatre and became a "genuine movie addict".[23] At the same time, a romantic involvement led to a physical confrontation with his father which resulted in a break in their relationship which lasted for many years. Although he did not graduate from the university, he wrote a number of plays and an opera, and became an assistant director at a local theatre. In 1942, he was given the opportunity to direct one of his own scripts, Caspar's Death. The play was seen by members of Svensk Filmindustri, which then offered Bergman a position working on scripts. He married Else Fisher in 1943.

Bergman's film career began in 1941 with his work rewriting scripts, but his first major accomplishment was in 1944 when he wrote the screenplay for Torment (a.k.a. Frenzy) (Hets), a film directed by Alf Sjöberg. Along with writing the screenplay, he was also appointed assistant director of the film. In his second autobiographical book, Images: My Life in Film, Bergman describes the filming of the exteriors as his actual film directorial debut.[24] The film sparked debate on Swedish formal education. When Henning Håkanson (the principal of the high school Bergman had attended) wrote a letter following the film's release, Bergman, according to scholar Frank Gado, disparaged in a response what he viewed as Håkanson's implication that students "who did not fit some arbitrary prescription of worthiness deserved the system's cruel neglect".[17] Bergman also stated in the letter that he "hated school as a principle, as a system and as an institution. And as such I have definitely not wanted to criticize my own school, but all schools."[25][26] The international success of this film led to Bergman's first opportunity to direct a year later. During the next ten years he wrote and directed more than a dozen films, including Prison (Fängelse) in 1949, as well as Sawdust and Tinsel (Gycklarnas afton) and Summer with Monika (Sommaren med Monika), both released in 1953.

Bergman first achieved worldwide success with Smiles of a Summer Night (Sommarnattens leende, 1955), which won for "Best poetic humour" and was nominated for the Palme d'Or at Cannes the following year. This was followed by The Seventh Seal (Det sjunde inseglet) and Wild Strawberries (Smultronstället), released in Sweden ten months apart in 1957. The Seventh Seal won a special jury prize and was nominated for the Palme d'Or at Cannes, and Wild Strawberries won numerous awards for Bergman and its star, Victor Sjöström. Bergman continued to be productive for the next two decades. From the early 1960s, he spent much of his life on the island of Fårö, where he made several films.

In the early 1960s he directed three films that explored the theme of faith and doubt in God, Through a Glass Darkly (Såsom i en Spegel, 1961), Winter Light (Nattvardsgästerna, 1962), and The Silence (Tystnaden, 1963). Critics created the notion that the common themes in these three films made them a trilogy or cinematic triptych. Bergman initially responded that he did not plan these three films as a trilogy and that he could not see any common motifs in them, but he later seemed to adopt the notion, with some equivocation.[27][28] His parody of the films of Federico Fellini, All These Women (För att inte tala om alla dessa kvinnor) was released in 1964.[29]

Persona (1966), starring Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann, is a film Bergman considered one of his most important works. While the highly experimental film won few awards, it has been considered his masterpiece. Other films of the period include The Virgin Spring (Jungfrukällan, 1960), Hour of the Wolf (Vargtimmen, 1968), Shame (Skammen, 1968) and The Passion of Anna (En Passion, 1969). With his cinematographer Sven Nykvist, Bergman made use of a crimson color scheme for Cries and Whispers (1972), which received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Picture.[30] He also produced extensively for Swedish television at this time. Two works of note were Scenes from a Marriage (Scener ur ett äktenskap, 1973) and The Magic Flute (Trollflöjten, 1975).

On 30 January 1976, while rehearsing August Strindberg's The Dance of Death at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm, he was arrested by two plainclothes police officers and charged with income tax evasion. The impact of the event on Bergman was devastating. He suffered a nervous breakdown as a result of the humiliation, and was hospitalised in a state of deep depression.

The investigation was focused on an alleged 1970 transaction of 500,000 Swedish kronor (SEK) between Bergman's Swedish company Cinematograf and its Swiss subsidiary Persona, an entity that was mainly used for the paying of salaries to foreign actors. Bergman dissolved Persona in 1974 after having been notified by the Swedish Central Bank and subsequently reported the income. On 23 March 1976, the special prosecutor Anders Nordenadler dropped the charges against Bergman, saying that the alleged crime had no legal basis, saying it would be like bringing "charges against a person who has stolen his own car, thinking it was someone else's".[31] Director General Gösta S Ekman, chief of the Swedish Internal Revenue Service, defended the failed investigation, saying that the investigation was dealing with important legal material and that Bergman was treated just like any other suspect. He expressed regret that Bergman had left the country, hoping that Bergman was a "stronger" person now when the investigation had shown that he had not done any wrong.[32]

Although the charges were dropped, Bergman became disconsolate, fearing he would never again return to directing. Despite pleas by the Swedish prime minister Olof Palme, high public figures, and leaders of the film industry, he vowed never to work in Sweden again. He closed down his studio on the island of Fårö, suspended two announced film projects, and went into self-imposed exile in Munich, West Germany. Harry Schein, director of the Swedish Film Institute, estimated the immediate damage as ten million SEK (kronor) and hundreds of jobs lost.[33]

Bergman then briefly considered the possibility of working in America; his next film, The Serpent's Egg (1977) was a West German-U.S. production and his second English-language film (the first being The Touch, 1971). This was followed by a British-Norwegian co-production, Autumn Sonata (Höstsonaten, 1978) starring Ingrid Bergman (no relation) and Liv Ullmann, and From the Life of the Marionettes (Aus dem Leben der Marionetten, 1980) which was a British-West German co-production.

He temporarily returned to his homeland to direct Fanny and Alexander (Fanny och Alexander, 1982). Bergman stated that the film would be his last, and that afterwards he would focus on directing theatre. After that he wrote several film scripts and directed a number of television specials. As with previous work for television, some of these productions were later theatrically released. The last such work was Saraband (2003), a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage and directed by Bergman when he was 84 years old.

Although he continued to operate from Munich, by mid-1978 Bergman had overcome some of his bitterness toward the Swedish government. In July of that year he visited Sweden, celebrating his sixtieth birthday on the island of Fårö, and partly resumed his work as a director at Royal Dramatic Theatre. To honour his return, the Swedish Film Institute launched a new Ingmar Bergman Prize to be awarded annually for excellence in filmmaking.[34] Still, he remained in Munich until 1984. In one of the last major interviews with Bergman, conducted in 2005 on the island of Fårö, Bergman said that despite being active during the exile, he had effectively lost eight years of his professional life.[35]

Bergman retired from filmmaking in December 2003. He had hip surgery in October 2006 and was making a difficult recovery. He died in his sleep[36] at age 89; his body was found at his home on the island of Fårö, on 30 July 2007.[37] It was the same day another renowned existentialist film director, Michelangelo Antonioni, died. The interment was private, at the Fårö Church on 18 August 2007. A place in the Fårö churchyard was prepared for him under heavy secrecy. Although he was buried on the island of Fårö, his name and date of birth were inscribed under his wife's name on a tomb at Roslagsbro churchyard, Norrtälje Municipality, several years before his death.

|

Main article: Ingmar Bergman filmography |