| Mule | |

|---|---|

| |

Domesticated

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Tribe: | Equini |

| Genus: | Equus |

| Species: | |

The mule is a domestic equine hybrid between a donkey and a horse. It is the offspring of a male donkey (a jack) and a female horse (a mare).[1][2] The horse and the donkey are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes; of the two possible first-generation hybrids between them, the mule is easier to obtain and more common than the hinny, which is the offspring of a male horse (a stallion) and a female donkey (a jenny).

Mules vary widely in size, and may be of any color. They are more patient, hardier and longer-lived than horses, and are perceived as less obstinate and more intelligent than donkeys.[3]: 5

A female mule that has oestrus cycles, and so could, in theory, carry a foetus, is called a "molly" or "Molly mule", although the term is sometimes used to refer to female mules in general. A male mule is properly called a "horse mule", although it is often called a "john mule", which is the correct term for a gelded mule. A young male mule is called a "mule colt", and a young female is called a "mule filly".[4]

Breeding of mules became possible only when the range of the domestic horse, which originated in Central Asia in about 3500 BC, extended into that of the domestic ass, which originated in north-eastern Africa. This overlap probably occurred in Anatolia and Mesopotamia in Western Asia, and mules were bred there before 1000 BC.[5]: 37

A painting in the Tomb of Nebamun at Thebes, dating from approximately 1350 BC, shows a chariot drawn by a pair of animals which have been variously identified as onagers,[6] as mules[5]: 37 or as hinnies.[7]: 96 Mules were present in Israel and Judah in the time of King David.[5]: 37 There are many representations of them in Mesopotamian works of art dating from the first millennium BC. Among the bas-reliefs depicting the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal from the North Palace of Nineveh is a clear and detailed image of two mules loaded with nets for hunting.[7]: 96 [8]

Homer noted their arrival in Asia Minor in the Iliad in 800 BC.[9]

Christopher Columbus allegedly brought mules to the New World.[10][better source needed]

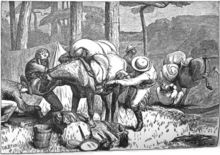

George Washington bred mules at his Mount Vernon home. At the time, they were not common in the United States, but Washington understood their value, as they were "more docile than donkeys and cheap to maintain."[11] In the nineteenth century, they were used in various capacities as draught animals – on farms, especially where clay made the soil slippery and sticky; pulling canal boats; and famously for pulling, often in teams of 20 or more animals, wagonloads of borax out of Death Valley, California from 1883 to 1889. The wagons were among the largest ever pulled by draught animals, designed to carry 10 short tons (9 metric tons) of borax ore at a time.[12]

Mules were used by armies to transport supplies, occasionally as mobile firing platforms for smaller cannons, and to pull heavier field guns with wheels over mountainous trails such as in Afghanistan during the Second Anglo-Afghan War.[13]

In the second half of the twentieth century, widespread use of mules declined in industrialised countries. The use of mules for farming and for transportation of agricultural products largely gave way to steam-, then diesel-powered, tractors and lorries.[citation needed] On 5 May 2003, Idaho Gem, a mule foal cloned by nuclear transfer of cells from foetal material, was born at the University of Idaho in Moscow, Idaho.[14]: 2924 [15] Neither an equid nor a hybrid animal had been cloned before.[14]: 2924 [15]

In general terms, in both the mule and the hinny, the foreparts and head of the animal are similar to those of the father sire, while the hindparts and tail tend to resemble those of the dam.[5]: 36 A mule is generally larger than a hinny, with longer ears and a heavier head; the tail is usually covered with long hair like that of its mare mother.[5]: 37 A mule has the thin limbs, small narrow hooves and short mane of the donkey, while its height, the shape of the neck and body, and the uniformity of its coat and teeth are more similar to those of the horse.[16]

Mules vary widely in size, from small miniature mules under 125 cm (50 in) to large and powerful draught mules standing up to 180 cm (70 in) at the withers.[17]: 86 The median weight range is between about 370 and 460 kg (820 and 1000 lb).[18]

The coat may be of any color seen in the horse or in the donkey. Mules usually display the light points commonly seen in donkeys: pale or mealy areas on the belly and the insides of the thighs, on the muzzle, and around the eyes. They often have primitive markings such as dorsal stripe, shoulder stripe or zebra stripes on the legs.[5]: 37

The mule exhibits hybrid vigor.[19] Charles Darwin wrote: "The mule always appears to me a most surprising animal. That a hybrid should possess more reason, memory, obstinacy, social affection, powers of muscular endurance, and length of life, than either of its parents, seems to indicate that art has here outdone nature".[20]

The mule inherits from the donkey the traits of intelligence, sure-footedness, toughness, endurance, disposition, and natural cautiousness. From the horse it inherits speed, conformation, and agility.[21]: 5–6, 8 Mules are reputed to exhibit a higher cognitive intelligence than their parent species, but robust scientific evidence to back up these claims is lacking. Preliminary data exist from at least two evidence-based studies, but they rely on a limited set of specialized cognitive tests and a small number of subjects.[22][23] Mules are generally taller at the shoulder than donkeys and have better endurance than horses, although a lower top speed.[22]

In the early twentieth century the mule was preferred to the horse as a pack animal – its skin is harder and less sensitive than that of a horse, and it is better able to bear heavy weights.[16]

A mule has 63 chromosomes, intermediate between the 64 of the horse and the 62 of the donkey.[24] Mules are usually infertile for this reason.[25]

Pregnancy is rare, but can occasionally occur naturally, as well as through embryo transfer. A few mare mules have produced offspring when mated with a horse or donkey stallion.[26][27] Herodotus gives an account of such an event as an ill omen of Xerxes' invasion of Greece in 480 BC: "There happened also a portent of another kind while he was still at Sardis—a mule brought forth young and gave birth to a mule" (Herodotus The Histories 7:57), and a mule's giving birth was a frequently recorded portent in antiquity, although scientific writers also doubted whether it was really possible (see e.g. Aristotle, Historia animalium, 6.24; Varro, De re rustica, 2.1.28). Between 1527 and 2002, approximately sixty such births were reported.[27] In Morocco in early 2002 and Colorado in 2007, mare mules produced colts.[27][28][29] Blood and hair samples from the Colorado birth verified that the mother was indeed a mule and the foal was indeed her offspring.[29]

A 1939 article in the Journal of Heredity describes two offspring of a fertile mare mule named "Old Bec," which was owned at the time by Texas A&M University in the late 1920s. One of the foals was a female, sired by a jack. Unlike her mother, she was sterile. The other, sired by a five-gaited Saddlebred stallion, exhibited no characteristics of any donkey. That horse, a stallion, was bred to several mares, which gave birth to live foals that showed no characteristics of the donkey.[30] In 1995, a group from the Federal University of Minas Gerais described a female mule that was pregnant for a seventh time, having previously produced two donkey sires, two foals with the typical 63 chromosomes of mules, and several horse stallions that had produced four foals. The three of the latter available for testing each bore 64 horse-like chromosomes. These foals phenotypically resembled horses, though they bore markings absent from the sire's known lineages, and one had ears noticeably longer than those typical of her sire's breed. The elder two horse-like foals had proved fertile at the time of publication, with their progeny being typical of horses.[31]

While a few mules can carry live weight up to 160 kg (353 lb), the superiority of the mule becomes apparent in their additional endurance.[32] In general, a mule can be packed with dead weight up to 20% of its body weight, or around 90 kg (198 lb).[32] Although it depends on the individual animal, mules trained by the Army of Pakistan are reported to be able to carry up to 72 kg (159 lb) and walk 26 km (16.2 mi) without resting.[33] The average equine in general can carry up to roughly 30% of its body weight in live weight, such as a rider.[34]

About 3.5 million donkeys and mules are slaughtered each year for meat worldwide.[35]

Mule trains have been part of working portions of transportation links as recently as 2005 by the World Food Programme,[36] and are still used extensively to transport cargo in rugged, roadless regions.[citation needed]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations reports that China was the top market for mules in 2003, closely followed by Mexico and many Central and South American nations.[citation needed]