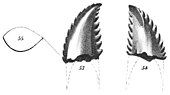

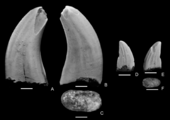

This timeline of troodontid research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on the troodontids, a group of bird-like theropod dinosaurs including animals like Troodon. Troodontid remains were among the first dinosaur fossils to be reported from North America after paleontologists began performing research on the continent, specifically the genus Troodon itself.[1] Since the type specimen of this genus was only a tooth and Troodon teeth are unusually similar to those of the unrelated thick-headed pachycephalosaurs, Troodon and its relatives would be embroiled in taxonomic confusion for over a century. Troodon was finally recognized as distinct from the pachycephalosaurs by Phil Currie in 1987. By that time many other species now recognized as troodontid had been discovered but had been classified in the family Saurornithoididae. Since these families were the same but the Troodontidae named first, it carries scientific legitimacy.[2]

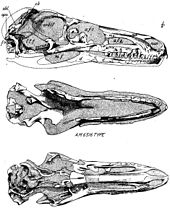

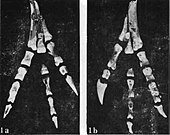

Many milestones of troodontid research occurred between the description of Troodon and the resolution of their confusion with pachycephalosaurs. The family itself was named by Charles Whitney Gilmore in 1924.[2] That same year Henry Fairfield Osborn named the genus Saurornithoides.[3] In the 1960s and 1970s researchers like Russell and Hopson observed that troodontids had very large brains for their body size. Both attributed this enlargement of the brain to a need for processing the animal's especially sharp senses.[4] Also in the 1970s, Barsbold described the new species Saurornithoides (now Zanabazar) junior[3] and named the family Saurornithoidae, but as noted this was just a junior synonym of the Troodontidae in the first place.[2]

In the 1980s Gauthier classed them with the dromaeosaurids in the Deinonychosauria.[2] That same decade Jack Horner reported the discovery of Troodon nests in Montana.[5] Interest in the life history of Troodon continued in the 1990s with a study of its growth rates based on histological sections of fossils taken from a bonebed in Montana[4] and the apparent pairing of eggs in Troodon nests.[5] This decade also saw the first potential report of European troodontid remains, although this claim has been controversial.[4] A single mysterious tooth from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of the United States was described as the oldest known troodontid remains, although this has also been controversial.[2] In the 2000s, several new kinds of troodontid were named, like Byronosaurus and Sinovenator.[3]