The History of Science Portal

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as alchemy and astrology during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, classical antiquity, and the Middle Ages declined during the early modern period after the establishment of formal disciplines of science in the Age of Enlightenment.

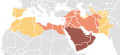

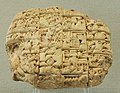

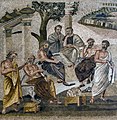

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3000 to 1200 BCE. These civilizations' contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced later Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages, but continued to thrive in the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the Hellenistic worldview was preserved and absorbed into the Arabic-speaking Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West. Traditions of early science were also developed in ancient India and separately in ancient China, the Chinese model having influenced Vietnam, Korea and Japan before Western exploration. Among the Pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica, the Zapotec civilization established their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics for producing calendars, followed by other civilizations such as the Maya.

Natural philosophy was transformed during the Scientific Revolution in 16th- to 17th-century Europe, as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The New Science that emerged was more mechanistic in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined scientific method. More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The chemical revolution of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for chemistry. In the 19th century, new perspectives regarding the conservation of energy, age of Earth, and evolution came into focus. And in the 20th century, new discoveries in genetics and physics laid the foundations for new sub disciplines such as molecular biology and particle physics. Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science," particularly after World War II. (Full article...)

Selected article -

Fizeau–Foucault apparatus may refer to either of two nineteenth-century experiments to measure the speed of light:

- Fizeau's measurement of the speed of light in air, using a toothed wheel

- Foucault's measurements of the speed of light, using a rotating mirror (Full article...)

Selected image

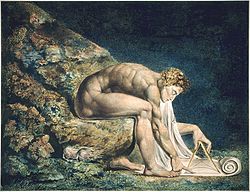

Poet and artist William Blake criticized Newton and like-minded philosophers such as Locke and Bacon for relying solely on reason.

Blake's 1795 print Newton is a demonstration of his opposition to the "single-vision" of scientific materialism: the great philosopher-scientist is shown utterly isolated in the depths of the ocean, his eyes (only one of which is visible) fixed on the compasses with which he draws on a scroll. His concentration is so fierce that he seems almost to become part of the rocks upon which he sits.

Did you know

...that in the history of paleontology, very few naturalists before the 17th century recognized fossils as the remains of living organisms?

...that on January 17, 2007, the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved to "5 minutes from midnight" in part because of global climate change?

...that in 1835, Caroline Herschel and Mary Fairfax Somerville became the first women scientists to be elected to the Royal Astronomical Society?

Selected Biography -

George Ledyard Stebbins Jr. (January 6, 1906 – January 19, 2000) was an American botanist and geneticist who is widely regarded as one of the leading evolutionary biologists of the 20th century. Stebbins received his Ph.D. in botany from Harvard University in 1931. He went on to the University of California, Berkeley, where his work with E. B. Babcock on the genetic evolution of plant species, and his association with a group of evolutionary biologists known as the Bay Area Biosystematists, led him to develop a comprehensive synthesis of plant evolution incorporating genetics.

His most important publication was Variation and Evolution in Plants, which combined genetics and Darwin's theory of natural selection to describe plant speciation. It is regarded as one of the main publications which formed the core of the modern synthesis and still provides the conceptual framework for research in plant evolutionary biology; according to Ernst Mayr, "Few later works dealing with the evolutionary systematics of plants have not been very deeply affected by Stebbins' work." He also researched and wrote widely on the role of hybridization and polyploidy in speciation and plant evolution; his work in this area has had a lasting influence on research in the field. (Full article...)Selected anniversaries

July 7:

- 1746 - Birth of Giuseppe Piazzi, Italian astronomer (d. 1826)

- 1878 - Death of Yegor Ivanovich Zolotarev, Russian mathematician (b. 1847)

- 1906 - Birth of William Feller, Croatian mathematician (d. 1970)

- 1927 - Death of Gösta Mittag-Leffler, Swedish mathematician (b. 1846)

Related portals

Topics

General images

Subcategories

Things you can do

Help out by participating in the History of Science Wikiproject (which also coordinates the histories of medicine, technology and philosophy of science) or join the discussion.

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus