Albert Otto Hirschman | |

|---|---|

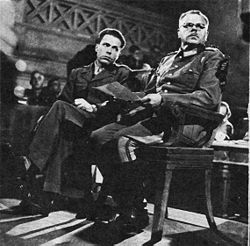

Hirschman (left) interpreting for the accused German Anton Dostler in Italy 1945 | |

| Born | April 7, 1915 |

| Died | December 10, 2012 (aged 97) |

| Academic career | |

| Institutions | |

| Field | Political economy |

| Alma mater | University of Trieste London School of Economics University of Paris HEC Paris |

| Contributions | Hiding hand principle |

| Information at IDEAS / RePEc | |

Albert Otto Hirschman[1] (born Otto-Albert Hirschmann; April 7, 1915 – December 10, 2012) was a German economist and the author of several books on political economy and political ideology. His first major contribution was in the area of development economics.[2] Here he emphasized the need for unbalanced growth. He argued that disequilibria should be encouraged to stimulate growth and help mobilize resources, because developing countries are short of decision-making skills. Key to this was encouraging industries with many linkages to other firms.

His later work was in political economy and there he advanced two schemata. The first describes the three basic possible responses to decline in firms or polities (quitting, speaking up, staying quiet) in Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970).[3] The second describes the basic arguments made by conservatives (perversity, futility and jeopardy) in The Rhetoric of Reaction (1991).

In World War II, he played a key role in rescuing refugees in occupied France.[4]

Early life and education

[edit]Otto Albert Hirschman was born in 1915 into an affluent Jewish family in Berlin, Germany, the son of Carl Hirschmann, a surgeon,[5] and Hedwig Marcuse Hirschmann. He had a sister, Ursula Hirschmann.[6] In 1932, he started studying at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, where he was active in the anti-fascist resistance. He emigrated to Paris,[7] where he continued his studies at HEC Paris and the Sorbonne. Then he was off to the London School of Economics and the University of Trieste, where he received his doctorate in economics in 1938.[6]

However, he had taken one break in the summer of 1936 to spend three months as a volunteer fighting on behalf of the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War.[5][6] This experience helped him when, after France’s 1940 surrender to the Nazis during World War II, he worked with Varian Fry from the Emergency Rescue Committee to help many of Europe's leading artists and intellectuals escape from occupied France to Spain through paths in the Pyrenees Mountains and then to Portugal,[5][8] with their exodus to end in the United States.[5] Those rescued included Marc Chagall, Hannah Arendt, and Marcel Duchamp.[8] Hirschman's participation in these rescues are one aspect of the 2023 Netflix series Transatlantic, in which a fictionalized version of him is played by Lucas Englander.[9]

Life and Career

[edit]From 1941 to 1943 he was a Rockefeller Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley. From 1943 to 1946 he was in the United States Army, where he worked in the Office of Strategic Services (the forerunner of the CIA). Among his tasks was serving as the interpreter for German general Anton Dostler at an early Allied war crimes trial.[10][11]

He was chief of the Western European and British Commonwealth Section of the Federal Reserve Board from 1946 to 1952.[12] In this role, he conducted and published analyses of postwar European reconstruction and newly created international economic institutions.[12] From 1952 to 1954 he was a financial advisor to the National Planning Board of Colombia; he stayed in Bogotá for another 2 years and worked as a private economic counselor.[citation needed]

Thereafter he held a succession of academic appointments in the economics departments of Yale University (1956–58), Columbia University (1958-64), and Harvard University (1964–74). He was on the Faculty of Social Science of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton from 1974 to 2012 until his death.[3]

He died at the age of 97 on December 10, 2012, just months after the passing of his wife of over 70 years, Sarah Hirschman (née Chapiro).[13]

Work

[edit]His first major contribution was in the area of development economics with the 1958 book The Strategy of Economic Development. Here he emphasized the need for unbalanced growth. He argued that disequilibria should be encouraged to stimulate growth and help mobilize resources, because developing countries are short of decision-making skills. Key to this was encouraging industries with many linkages to other firms.[citation needed] He argued against "Big Push" approaches to development, such as those advocated by Paul Rosenstein-Rodan.[14]

In the 1960s, Hirschman praised the works of Peruvian intellectuals José Carlos Mariátegui and Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, stating "paradoxically, the most ambitious attempt to theorize the revolution of Latin American society arose in a country that to date has experienced very little social change: I am talking about Peru and the writings of Haya de la Torre and Mariátegui".[15] He helped develop the hiding hand principle in his 1967 essay The principle of the hiding hand,.[citation needed]

His later work was in political economy, where he advanced two schemata. In Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970) he described the three basic possible responses to decline in firms or polities (quitting, speaking up, staying quiet).[3] The second systematizes the basic arguments made by conservatives (perversity, futility and jeopardy) in The Rhetoric of Reaction (1991).

In The Passions and the Interests Hirschmann recounts a history of the ideas laying the intellectual groundwork for capitalism. He describes how thinkers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries embraced the sin of avarice as an important counterweight to humankind's destructive passions. Capitalism was promoted by thinkers including Montesquieu, Sir James Steuart, and Adam Smith as repressing the passions for "harmless" commercial activities. Hirschman noted that terms including "vice" and "passion" gave way to "such bland terms" as "advantage" and "interest."[citation needed] Hirschman described it as the book he most enjoyed writing.[citation needed] According to Hirschman biographer Jeremy Adelman, it reflected Hirschman's political moderation, a challenge to reductive accounts of human nature by economists as a "utility-maximizing machine" as well as Marxian or communitarian "nostalgia for a world that was lost to consumer avarice."[16][page needed]

Herfindahl–Hirschman Index

[edit]In 1945, Hirschman proposed a market concentration index which was the square root of the sum of the squares of the market share of each participant in the market.[17] In 1950, Orris C. Herfindahl proposed a similar index (but without the square root), apparently unaware of the prior work.[18] Thus, it is usually referred to as the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index.

Books

[edit]- 1945. National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade 1980 expanded ed., Berkeley : University of California Press[17]

- 1955. Colombia; highlights of a developing economy. Bogotá: Banco de la Republica Press.

- 1958. The Strategy of Economic Development. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-00559-8

- 1961. Latin American issues; essays and comments New York: Twentieth Century Fund.

- 1963. Journeys toward Progress: Studies of Economic Policy-Making in Latin America. New York: Twentieth Century Fund

- 1967. Development Projects Observed. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution. ISBN 0-815-73651-7 (paper).

- 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-27660-4 (paper).

- 1971. A Bias for Hope: Essays on Development and Latin America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- 1977. The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments For Capitalism Before Its Triumph. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01598-8.

- 1980. National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- 1981. Essays in trespassing: economics to politics and beyond. Cambridge (Eng.); New York: Cambridge University Press.

- 1982. Shifting involvements: private interest and public action. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- 1984. Getting ahead collectively: grassroots experiences in Latin America (with photographs by Mitchell Denburg). New York: Pergamon Press

- 1985. A bias for hope: essays on development and Latin America. Boulder: Westview Press.

- 1986. Rival views of market society and other recent essays. New York: Viking.

- 1991. The Rhetoric of Reaction: Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-76867-1 (cloth) and ISBN 0-674-76868-X (paper).

- 1995. A propensity to self-subversion. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- 1998. Crossing boundaries: selected writings. New York: Zone Books; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Distributed by the MIT Press.

- 2013. Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman by Jeremy Adelman. ISBN 9780691155678. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ (2013)

- 2013. The Essential Hirschman edited by Jeremy Adelman (Princeton University Press) 384 pages; 16 essays

Selected articles

[edit]- "On Measures of Dispersion for a Finite Distribution." Journal of the American Statistical Association 38, no. 223 (September 1943): 346–352.

- "The Commodity Structure of World Trade." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 57, no. 4 (August 1943): 565–595.

- "Devaluation and the Trade Balance: A Note." The Review of Economics and Statistics 31, no. 1 (February 1949): 50–53.

- "Negotiations and the Issues." The Review of Economics and Statistics, 33, no. 1 (February 1951): 49–55.

- "Types of Convertibility." The Review of Economics and Statistics, 33, no. 1 (February 1951): 60–62.

- "Currency Appreciation as an Anti-Inflationary Device: Further Comment." The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 66, no. 1 (February 1952): 117–120.

- "Economic Policy in Underdeveloped Countries." Economic Development and Cultural Change, 5, no. 4 (July 1957): 362–370.

- "Investment Policies and 'Dualism' in Underdeveloped Countries." The American Economic Review 47, no. 5 (September 1957): 550–570.

- "Invitation to Theorizing about the Dollar Glut." The Review of Economics and Statistics 42, no. 1 (February 1960): 100–102.

- "The Commodity Structure of World Trade: Reply." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 75, no. 1 (February 1961): 165–166.

- "Models of Reformmongering." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 77, no. 2 (May 1963): 236–257.

- "Obstacles to Development: A Classification and a Quasi-Vanishing Act." Economic Development and Cultural Change 13, no. 4 (July 1965): 385–393.

- "The Political Economy of Import-Substituting Industrialization in Latin America." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 82, no. 1 (February 1968): 1–32.

- "Underdevelopment, Obstacles to the Perception of Change, and Leadership." Daedalus 97, no. 3 (Summer 1968): 925–937.

- "An Alternative Explanation of Contemporary Harriednes." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 87, no. 4 (November 1973): 634–637.

- "The Changing Tolerance for Income Inequality in the Course of Economic Development", World Development, Vol. 1, No. 12, (December 1973).

- "On Hegel, Imperialism, and Structural Stagnation", Journal of Development Economics 3 (1976): 1–8. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(76)90037-7

- "Beyond Asymmetry: Critical Notes on Myself as a Young Man and on Some Other Old Friends." International Organization 32, no. 1 (Winter 1978): 45–50.

- "Exit, Voice, and the State." World Politics 31, no. 1 (October 1978): 90–107.

- "The Rise and Decline of Development Economics." International Symposium on Latin America, Bar-Ilan University, Israel, 1980.

- "'Exit, Voice, and Loyalty': Further Reflections and a Survey of Recent Contributions." The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health and Society 58, no. 3 (Summer 1980): 430–453.

- "Rival Interpretations of Market Society: Civilizing, Destructive, or Feeble?." Journal of Economic Literature 20, no. 4 (December 1982): 1463–1484.

- "Against Parsimony: Three Easy Ways of Complicating Some Categories of Economic Discourse." Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 37, no. 8 (May 1984): 11–28.

- "Against Parsimony: Three Easy Ways of Complicating Some Categories of Economic Discourse." American Economic Review 72, no. 2 (1984): 89–96

- "University Activities Abroad and Human Rights Violations: Exit, Voice, or Business as Usual." Human Rights Quarterly 6, no. 1 (February 1984): 21–26.

- "The Political Economy of Latin American Development: Seven Exercises in Retrospection." Latin American Research Review 22, no. 3 (1987): 7–36.

- "Exit, Voice, and the Fate of the German Democratic Republic: An Essay in Conceptual History." World Politics 45, no. 2 (January 1993): 173–202.

- "Social Conflicts as Pillars of Democratic Market Society." Political Theory 22, no. 2 (May 1994): 203–218.

Awards

[edit]Hirschman was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1965),[19] the American Philosophical Society (1979),[20] and the United States National Academy of Sciences (1987).[21]

In 2001, Hirschman was named among the top 100 American intellectuals, as measured by academic citations, in Richard Posner's book, Public Intellectuals: A Study of Decline.[22]

In 2002, Hirschman was awarded Doctor Honoris Causa by the European University Institute, Florence, Italy.[23]

In 2003, he won the Benjamin E. Lippincott Award from the American Political Science Association to recognize a work of exceptional quality by a living political theorist for his book The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments for Capitalism before Its Triumph.[citation needed]

In 2007, the Social Science Research Council established an annual prize in honor of Hirschman.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ or Hirshman.

- ^ Hirschman, A. O. (1958) The Strategy of Economic Development. Yale University Press

- ^ a b c Dowding, Keith (March 26, 2015). Lodge, Martin; Page, Edward C; Balla, Steven J (eds.). "Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States". The Oxford Handbook of Classics in Public Policy and Administration. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199646135.013.30. ISBN 978-0-19-964613-5. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ Kuttner, Robert (May 16, 2013). "Rediscovering Albert Hirschman". The American Prospect. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Book review of “Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman” (Princeton), by Jeremy Adelman : The Gift of Doubt: Albert O. Hirschman and the power of failure by Malcolm Gladwell Archived July 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine The New Yorker, 2013

- ^ a b c (in German) Honorary degree awarded to Albert O. Hirschman Archived July 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine by Free University of Berlin

- ^ Löhr, Isabella (January 15, 2014). "Jeremy Adelman, Worldly Philosopher. The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman. Princeton/Oxford, Princeton University Press 2013". Historische Zeitschrift. 299 (2): 573–576. doi:10.1515/hzhz-2014-0531. ISSN 2196-680X.

- ^ a b Yardley, William (December 23, 2012). "Albert Hirschman, Optimistic Economist, Dies at 97". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (April 10, 2023). "Meet Lucas Englander, the 'Chameleon' of Transatlantic". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Yardley, William (December 23, 2012). "Albert Hirschman, Optimistic Economist, Dies at 97". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ Adelman, Jeremy. (2013). Worldly philosopher : the odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman. Princeton, NJ. ISBN 978-0-691-15567-8. OCLC 820123478.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Alacevich, Michele; Asso, Pier Francesco (2022). "Albert O. Hirschman, Europe, and the Postwar Economic Order, 1946–52". History of Political Economy. 55: 39–75. doi:10.1215/00182702-10213625. hdl:11585/914215. ISSN 0018-2702. S2CID 252975953.

- ^ Green, David (October 12, 2014). "Economist who studied progress and fought fascism dies". Ha’aretz. Archived from the original on January 6, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ Paul., Krugman (1999). Development, geography, and economic theory. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-61135-X. OCLC 742205196.

- ^ Orihuela, José Carlos (January–June 2020). "El consenso de Lima y sus descontentos: del restringido desarrollismo oligarca a revolucionarias reformas estructurales". Revista de historia. 27 (1). Concepción, Chile: 77–100. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Adelman, Jeremy (April 7, 2013). Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691155678.

- ^ a b Albert O. Hirschman (January 1, 1980). National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade. University of California Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-520-04082-3.

...there was a posterior inventor, O. C. Herfindahl, who proposed the same index, except for the square root...

- ^ Orris C Herfindahl (1950). Concentration in the steel industry. OCLC 5732189.

((cite book)):|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Albert Otto Hirschman". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ "Albert O. Hirschman". nasonline.org. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ Posner, Richard (2001). Public Intellectuals: A Study of Decline. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00633-1.

- ^ "Doctor Honoris Causa of the EUI and Recipients of Doctor Honoris Causa Degrees". European University Institute (EUI). Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Albert O. Hirschman Prize of the Social Science Research Council". Social Science Research Council. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- Sources

- Europa Publications (2003). The International Who's Who 2004. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-85743-217-6. Retrieved April 24, 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Michele Alacevich. 2021. Albert O. Hirschman: An Intellectual Biography. Columbia University Press.

- Jeremy Adelman. 2013. Worldly Philosopher: The Odyssey of Albert O. Hirschman. Princeton University Press

External links

[edit]- Albert Hirschman Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

- The New York Review of Books Bibliography

- Amherst Commencement Recognition

- Albert O. Hirschman Prize and Lecture Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Obituary from the Institute for Advanced Study Archived December 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "A great lateral thinker died on December 10th" The Economist 2012.

- Michael Laver. "Exit, Voice, and Loyalty revisited: The Strategic Production and Consumption of Public and Private Goods," British Journal of Political Science. Vol. 6. (Oct. 1976). pp. 463–482.

- Works by or about Albert O. Hirschman at Internet Archive

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Academics | |

| People | |

| Other | |