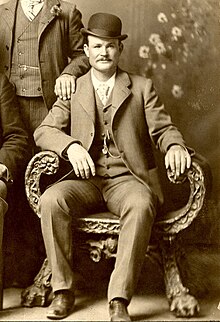

Butch Cassidy | |

|---|---|

Cassidy c. 1900 | |

| Born | Robert LeRoy Parker April 13, 1866 Beaver, Utah Territory, U.S. |

| Died | November 7, 1908 (aged 42) Bolivia |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Other names | Butch Cassidy, Mike Cassidy, George Cassidy, Jim Lowe, Santiago Maxwell |

| Occupation(s) | Farm hand, cowboy, butcher, thief, robber, gang leader, outlaw |

| Years active | 1889–1908 |

| Allegiance | Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch |

| Conviction(s) | Imprisoned in the territorial prison in Laramie, Wyoming for horse theft |

| Criminal charge | Horse theft, cattle rustling, bank and train robbery |

| Penalty | Served 18 months of a two-year sentence; released January 1896 |

Robert LeRoy Parker (April 13, 1866 – November 7, 1908), better known as Butch Cassidy,[1] was an American train and bank robber and the leader of a gang of criminal outlaws known as the "Wild Bunch" in the Old West.

Parker engaged in criminal activity for more than a decade at the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century, but the pressures of being pursued by law enforcement, notably the Pinkerton detective agency, forced him to flee the United States. He fled with his accomplice Harry Longabaugh, known as the "Sundance Kid", and Longabaugh's girlfriend Etta Place. The trio traveled first to Argentina and then to Bolivia, where Parker and Longabaugh are believed to have been killed in a shootout with the Bolivian Army in November 1908; the exact circumstances of their fate continue to be disputed.

Parker's life and death have been extensively dramatized in film, television and literature, and he remains one of the best-known icons of the "Wild West" mythos in modern times.

Robert LeRoy Parker was born on April 13, 1866, in Beaver, Utah Territory, the first of thirteen children of English immigrants Maximillian Parker and Ann Campbell Gillies.[2][3][4] The Parker and Gillies families had converted to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints while still living in the United Kingdom. Maximillian Parker was twelve years old when his family arrived in Salt Lake City in 1856 as Mormon pioneers.[5] Ann Gillies was born and lived in Sunderland in northeast England before immigrating to the U.S. with her family in 1859 at age 14.[6][7][8] The couple were married in July 1865.[9] Robert Parker grew up on his parents' ranch near Circleville.[10]

Parker fled his home as a teenager and, while working on a dairy ranch, met cattle thief Mike Cassidy. He subsequently worked on several ranches, in addition to a brief apprenticeship with a butcher in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory, where he got his nickname (by the word "butcher", which morphed later into "Butch"), to which he soon added the last name Cassidy in honor of his old friend and mentor.

Butch Cassidy's first criminal offense was minor. Around 1880 he journeyed to a clothier shop in another town but found it closed. He broke into the shop and stole a pair of jeans and some pie, leaving an IOU promising to pay on his next visit. The clothier pressed charges, but Cassidy was acquitted by a jury. He continued to work on ranches until 1884, when he moved to Telluride, Colorado, ostensibly to seek work, but perhaps to deliver stolen horses to buyers. Cassidy led a cowboy's life[vague] in Wyoming Territory and Montana Territory before returning to Telluride in 1887, where he met Matt Warner, the owner of a racehorse. Cassidy and Warner raced the horse at various events, dividing the winnings between them.

Cassidy's first bank robbery took place on June 24, 1889, when he, Warner, and two of the McCarty brothers robbed the San Miguel Valley Bank in Telluride. Businessman L. L. Nunn had taken a controlling interest in the bank the previous year.[11] The robbers stole around $21,000 (equivalent to $712,000 in 2023), after which they fled to the Robbers Roost, a remote hideout in the southeastern corner of Utah Territory.

In 1890, Cassidy purchased a ranch on the outskirts of Dubois, Wyoming. This location was across the state from the notorious Hole-in-the-Wall, a natural geological formation, and a popular hideout for outlaw gangs, including Cassidy's, during the era. Cassidy's ranching was possibly a façade for clandestine activities, perhaps with Hole-in-the-Wall outlaws, as he was never financially successful at ranching.[13] Cassidy's ranch used the "unmistakable brand" of "Reverse-E, Box, E".[12]

In early 1894, Cassidy became involved romantically with rancher and outlaw Ann Bassett. Her father was a rancher who did business with Cassidy, supplying him with fresh horses and beef. That same year, Cassidy was arrested at Lander, Wyoming, for stealing horses and possibly for running a protection racket among the local ranchers there. He was imprisoned in the Wyoming State Prison in Laramie, where he served eighteen months of a two-year sentence; he was released and pardoned in January 1896 by Governor William Alford Richards.[14] He became involved briefly with Bassett's older sister Josie before returning to Ann.

Cassidy associated with a wide circle of criminals, most notably his closest friend William Ellsworth "Elzy" Lay, Harvey "Kid Curry" Logan, Ben "The Tall Texan" Kilpatrick, Harry Tracy, Will "News" Carver, Laura Bullion and George "Flat Nose" Curry, who collectively became the so-called "Wild Bunch". The gang assembled sometime after Cassidy's release from prison in 1896 and took its name from the Doolin–Dalton gang, also known as the "Wild Bunch".[15]

On August 13, 1896, Cassidy, Lay, Logan and Bob Meeks[16] robbed the bank at Montpelier, Idaho, escaping with roughly $7,000. Cassidy recruited Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, also known as the "Sundance Kid", into the gang soon after.

Bassett, Lay and Lay's girlfriend Maude Davis all joined Cassidy at Robbers Roost in early 1897. The four hid there until early April, when Lay and Cassidy sent the women home so that the men could plan their next robbery. They ambushed a small group of men carrying the payroll of the Pleasant Valley Coal Company in the mining town of Castle Gate, Utah, on April 22, 1897, stealing a sack of silver coins, with which they fled back to the Robbers Roost.[17]

On June 2, 1899, the gang robbed a Union Pacific Overland Flyer passenger train near Wilcox, Wyoming, a robbery that earned them a great deal of notoriety and resulted in a massive manhunt.[18][19] Many notable lawmen took part in the hunt but did not find them. Kid Curry and George Curry had a shootout with lawmen following the train robbery, killing Sheriff Joe Hazen. Tom Horn, a killer-for-hire employed by the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, was told by explosives expert Bill Speck about the Hazen shooting. Pinkerton detective Charlie Siringo was then assigned the task of capturing the outlaws. He became friends with Elfie Landusky, who was using the last name Curry after becoming pregnant by Kid Curry's brother Lonny Logan, and Siringo intended to locate the gang through her.

On July 11, 1899, Lay and others were involved in a Colorado and Southern Railroad train robbery near Folsom, New Mexico, which Cassidy might have planned and personally directed. A shootout ensued with local law enforcement, during which Lay killed Sheriff Edward Farr and Henry Love; Lay was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment at the New Mexico State Penitentiary.

The Wild Bunch typically separated following a robbery and fled in different directions, later reuniting at a predetermined location such as the Hole-in-the-Wall, Robbers Roost, or Fannie Porter's brothel in San Antonio.

Cassidy approached Utah Governor Heber Wells to negotiate an amnesty. Wells advised him to ask the Union Pacific Railroad to drop their criminal complaints against him, and Union Pacific chairman E. H. Harriman attempted to meet with Cassidy through Warner. On August 29, 1900, Cassidy, Longabaugh, and others robbed Union Pacific train No. 3 near Tipton, Wyoming, breaking Cassidy's earlier promise to the governor of Wyoming and ending any chance for amnesty.

On February 28, 1900, lawmen attempted to arrest Lonny Logan at his aunt's home. Lonny was killed in the shootout that followed, and his cousin Bob Lee was arrested for rustling and sent to prison in Wyoming. On March 28, George Curry and News Carver were pursued by a posse from St. Johns, Apache County, Arizona, after using currency they had stolen in the Wilcox train robbery. The posse engaged them in a shootout, during which Deputies Andrew Gibbons and Frank LeSueur were killed, while Carver and Curry escaped. On April 17, George Curry was killed in a shootout with Grand County, Utah, Sheriff John Tyler and Deputy Sam Jenkins. On May 26, Kid Curry rode into Moab, Utah, and killed both Tyler and Jenkins in another shootout in retaliation for the deaths of George and Lonny.

In December, Cassidy posed alongside Longabaugh, Logan, Carver, and Ben Kilpatrick in Fort Worth, Texas, for the now-famous "Fort Worth Five" photograph. The Pinkerton Agency obtained a copy of the photograph and began to use it for wanted posters.

On July 3, 1901, Kid Curry and a group of men robbed a Great Northern train near Wagner, Montana,[20] stealing more than $60,000 in cash (equivalent to $2,200,000 in 2023). The gang split up, but a posse led by Sheriff Elijah Briant caught up with News Carver and killed him. Kilpatrick was captured in St. Louis on November 5 at Josie Blakey's resort on Chestnut Street. In his pocket, they found a key to a room at The Laclede Hotel. The next morning, they found Laura Bullion in the lobby, checking out with her luggage. In her valise was $8500 in unsigned banknotes from the Great Northern robbery. Curry killed Knoxville policemen William Dinwiddle and Robert Saylor in another shootout on December 13, then escaped. He returned to Montana, pursued by Pinkertons and other law enforcement officers, where he shot and killed rancher James Winters in retaliation for killing his brother Johnny years before.[21]

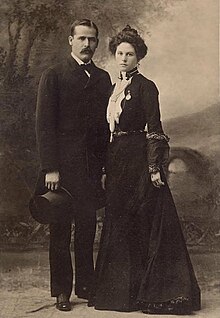

Cassidy and Longabaugh fled to New York City, feeling continuous pressure from the numerous law enforcement agencies pursuing them and seeing their gang falling apart. They departed from there to Buenos Aires, Argentina, aboard the British steamer Herminius on February 20, 1901,[22][23][24][25] along with Longabaugh's companion Etta Place. Cassidy posed as James Ryan, Place's fictitious brother. They settled in a four-room log cabin on a 15,000-acre (61 km2) ranch that they purchased on the east bank of the Rio Blanco near Cholila, just east of the Andes in Chubut.

Bruce Chatwin's In Patagonia references a letter Butch wrote from Cholila to Elza Lay's mother-in-law in Utah, dated August 10, 1902. The letter cites "our little family of 3" living in a 4 room house with 300 cattle, 1500 sheep, and 28 horses. Chatwin states the letter resides with the Utah State Historical Society.[26]

Two English-speaking bandits held up the Banco de Tarapacá y Argentino in Río Gallegos on February 14, 1905, 700 miles (1,100 km) south of Cholila near the Strait of Magellan, and the pair vanished north across the Patagonian grasslands. Cassidy and Longabaugh sold the Cholila ranch on May 1, fearing that law enforcement had located them. The Pinkerton Agency had known their location for some time, but the snow and the hard winter of Patagonia had prevented their agent Frank Dimaio from making an arrest. Governor Julio Lezana issued an arrest warrant, but Sheriff Edward Humphreys, a Welsh-Argentine who was friendly with Cassidy and enamored of Place, tipped them off. The trio then fled north to San Carlos de Bariloche, where they embarked on the steamer Condor across Nahuel Huapí Lake and into Chile; they returned to Argentina by the end of the year. Cassidy, Longabaugh, Place, and an unknown male associate robbed the Banco de la Nación Argentina branch in Villa Mercedes, San Luis Province on December 19, 450 miles (720 km) west of Buenos Aires, taking 12,000 pesos. They fled across the Andes to reach the safety of Chile.

On June 30, 1906, Place decided that she had enough of life on the run, so Longabaugh took her back to San Francisco. Cassidy obtained honest work under the alias James "Santiago" Maxwell at the Concordia Tin Mine in the Santa Vera Cruz range of the central Bolivian Andes, where Longabaugh joined him upon his return. Their main duties included guarding the company payroll. The two traveled to Santa Cruz in late 1907, a frontier town in Bolivia's eastern savannah, still wanting to settle down as respectable ranchers.

A courier was carrying the payroll for the Aramayo Franke and Cia Silver Mine on November 3, 1908, near the small mining town of San Vicente in southern Bolivia, when he was attacked by two masked American bandits believed to be Cassidy and Longabaugh. Witnesses saw them three days later in San Vicente, where they lodged in a small boarding house owned by miner Bonifacio Casasola.[27] Casasola became suspicious of them because they had a mule from the Aramayo Mine, identifiable from the company's brand. He notified a nearby telegraph officer, who notified the Abaroa cavalry regiment stationed nearby. The unit dispatched three soldiers under the command of Captain Justo Concha, and they notified the local authorities.

The soldiers, the police chief, the local mayor, and some of his officials all surrounded the lodging house on the evening of November 6, intending to arrest the Aramayo robbers. As they approached the house, the bandits opened fire, killing one of the soldiers and wounding another and starting a gunfight which lasted for several hours into the evening and the night. At around 2:00 am, during a lull in the fighting, the mayor heard a man scream three times inside the house, then two successive shots were fired from inside the house.[27]

The authorities entered the house the next morning, where they found two bodies with numerous bullet wounds to the arms and legs. The man assumed to be Longabaugh had a bullet wound in the forehead, and the man thought to be Cassidy had a bullet hole in the temple. The local police report speculated that judging from the positions of the bodies, Cassidy had probably shot the fatally wounded Longabaugh to put him out of his misery, then killed himself with his final bullet. The Tupiza police identified the bandits as the men who robbed the Aramayo payroll transport, but the Bolivian authorities did not know their real names, nor could they positively identify them.[27]

The two bodies were buried at the small San Vicente cemetery, near the grave of a German miner named Gustav Zimmer. American forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow and his researchers attempted to find the graves in 1991, but they did not find any remains with DNA matching the living relatives of Cassidy and Longabaugh.[27] Snow's search formed the basis of the British documentary Wanted - Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (Channel 4, April 22, 1993;[28][29] later screened on Nova, October 12, 1993[30]).

In 2017, a new search was launched for Cassidy's grave, which zeroed in on a mine outside Goodsprings, Nevada. The dig found human remains, but they did not match the DNA provided.[31]

John McPhee's Annals of the Former World repeats a story that Dr. Francis Smith told to geologist David Love in the 1930s. Smith stated that he had seen Cassidy, who told him that his face had been altered by a surgeon in Paris, and he showed Smith an old bullet wound that Smith recognized as work that he had done.[32]

Josie Bassett claimed in 1960 that Cassidy came to visit her in the 1920s "after returning from South America," and that he "died in Johnnie, Nevada[33] about 15 years ago."[34] Residents in Cassidy's hometown of Circleville, Utah, claimed in an interview that he worked in Nevada until his death.[35] Western historian Charles Kelly observed in his 1938 book The Outlaw Trail: A History of Butch Cassidy and His Wild Bunch, "it seems exceedingly strange" that Cassidy never returned to Circleville, Utah, to visit his father if he were still alive.[36] According to his great nephew, Bill Betenson, he did return to Utah to visit his family in Circleville many times.[37]

Bruce Chatwin, in his classic travel book In Patagonia, says, "I went to see the star witness; his sister, Mrs. Lulu [sic] Parker Betenson, a forthright and energetic woman in her nineties ... She has no doubts: her brother came back and ate blueberry pie with family at Circleville in ... 1925. She believes he died of pneumonia in Washington in the late 1930s."[38]

An episode of the television series In Search of... (1978) examined the claims and possible evidence for Cassidy's return to America during the 1920s in a series of interviews with residents of Baggs, Wyoming, a popular destination for the Wild Bunch during their raiding years. Residents claimed that Cassidy had visited for several days in 1924, driving a Ford Model T. Lula Parker-Betenson stated that he returned to the family home in Circleville during this period, and picked up his brother Mark in a Ford, then drove to their father's home,[39] where she also lived. Her father allegedly said to her, "I'll bet you don't know who this is. This is your brother Robert LeRoy." She stated that Cassidy was full of regrets, particularly at having disappointed his mother. She quoted him lamenting, "all I did is make a wreck of my life." Betenson claims that Cassidy lived out his years in "the Northwest" and died in 1937 and that the family had agreed not to disclose his final resting place, since "they had chased him all his life, and now he's going to rest in peace." This story is also recounted by W. C. Jameson in Butch Cassidy: Beyond the Grave,[40] referencing the 1975 book Betenson co-authored with Dora Flack, Butch Cassidy, My Brother.[15]

On an episode of the series Mission Declassified (2019), investigative journalist Christof Putzel met with local researcher Marilyn Grace at Cassidy's childhood log cabin on the Parker ranch in Circleville to talk about the alleged burial of Cassidy there on July 20, 1937. Grace explains that Cassidy was secretly buried at Tom's Cabin, a former sheepherders' log cabin located in a remote area of the property, a favorite camping spot for his brothers and him. Grace says an eyewitness, neighbor Dee Crosby, saw the burial take place at the cabin. Earlier, Putzel spoke to Alta Orton, another Parker neighbor, who described the family as having been dressed in funeral-like attire on that same day. Grace goes on to say that cadaver dogs had been brought to the cabin in an attempt to locate remains and led to a positive indication. The underside of the cabin was later dug and two bones discovered, identified as a human spinal bone and a toe bone. Putzel had forensic scientist Suzanna Ryan at Pure Gold Forensics in Redlands, California conduct a DNA test on the bones. Ryan confirmed they were human, but lacked enough DNA for a complete profile. As the site may have become public knowledge, the Parker family is believed to have since excavated Cassidy's remains at the cabin and moved them to a different burial site, leaving the spinal and toe bones behind in the process.[41]

William T. Phillips claimed to have known Cassidy since childhood.[44] In his book In Search of Butch Cassidy,[45] Larry Pointer speculated that Phillips was actually Cassidy, based upon stories in Phillips's unpublished manuscript, The Bandit Invincible, and a resemblance between the two men. In 2012, though, Pointer obtained a copy of the Wyoming Territorial Prison mugshot of William T. Wilcox, a previously unknown associate of Cassidy's. Observing the similarities between the two men, he revised his previous theory and concluded that Phillips was Wilcox, and not Cassidy.[46]