| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lanthanum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈlænθənəm/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery white | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(La) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lanthanum in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 57 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | f-block groups (no number) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | f-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 5d1 6s2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 18, 9, 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1193 K (920 °C, 1688 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3737 K (3464 °C, 6267 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at 20° C) | 6.145 g/cm3 [3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 5.94 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 6.20 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 400 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 27.11 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure (extrapolated)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 0,[4] +1,[5] +2, +3 (a strongly basic oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 187 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 207±8 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

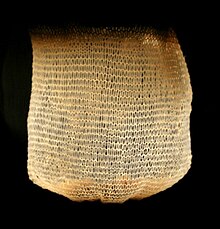

| Crystal structure | α form: double hexagonal close-packed (dhcp) (hP4) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constants | a = 0.37742 nm c = 1.2171 nm (at 20 °C)[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 5.1×10−6/K (at 20 °C)[3][a] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 13.4 W/(m⋅K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | α, poly: 615 nΩ⋅m (at r.t.) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +118.0×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | α form: 36.6 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | α form: 14.3 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | α form: 27.9 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 2475 m/s (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | α form: 0.280 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 360–1750 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 350–400 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7439-91-0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Carl Gustaf Mosander (1838) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of lanthanum | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lanthanum is a chemical element; it has symbol La and atomic number 57. It is a soft, ductile, silvery-white metal that tarnishes slowly when exposed to air. It is the eponym of the lanthanide series, a group of 15 similar elements between lanthanum and lutetium in the periodic table, of which lanthanum is the first and the prototype. Lanthanum is traditionally counted among the rare earth elements. Like most other rare earth elements, its usual oxidation state is +3, although some compounds are known with an oxidation state of +2. Lanthanum has no biological role in humans but is essential to some bacteria. It is not particularly toxic to humans but does show some antimicrobial activity.

Lanthanum usually occurs together with cerium and the other rare earth elements. Lanthanum was first found by the Swedish chemist Carl Gustaf Mosander in 1839 as an impurity in cerium nitrate – hence the name lanthanum, from the ancient Greek λανθάνειν (lanthanein), meaning 'to lie hidden'. Although it is classified as a rare earth element, lanthanum is the 28th most abundant element in the Earth's crust, almost three times as abundant as lead. In minerals such as monazite and bastnäsite, lanthanum composes about a quarter of the lanthanide content.[9] It is extracted from those minerals by a process of such complexity that pure lanthanum metal was not isolated until 1923.

Lanthanum compounds have numerous applications including catalysts, additives in glass, carbon arc lamps for studio lights and projectors, ignition elements in lighters and torches, electron cathodes, scintillators, and gas tungsten arc welding electrodes. Lanthanum carbonate is used as a phosphate binder to treat high levels of phosphate in the blood accompanied by kidney failure.

Characteristics

[edit]Physical

[edit]Lanthanum is the first element and prototype of the lanthanide series. In the periodic table, it appears to the right of the alkaline earth metal barium and to the left of the lanthanide cerium. Lanthanum is generally considered the first of the f-block elements by authors writing on the subject.[10][11][12][13][14] The 57 electrons of a lanthanum atom are arranged in the configuration [Xe]5d16s2, with three valence electrons outside the noble gas core. In chemical reactions, lanthanum almost always gives up these three valence electrons from the 5d and 6s subshells to form the +3 oxidation state, achieving the stable configuration of the preceding noble gas xenon.[15] Some lanthanum(II) compounds are also known, but they are usually much less stable.[16][17] Lanthanum monoxide (LaO) produces strong absorption bands in some stellar spectra.[18]

Among the lanthanides, lanthanum is exceptional as it has no 4f electrons as a single gas-phase atom. Thus it is only very weakly paramagnetic, unlike the strongly paramagnetic later lanthanides (with the exceptions of the last two, ytterbium and lutetium, where the 4f shell is completely full).[19] However, the 4f shell of lanthanum can become partially occupied in chemical environments and participate in chemical bonding.[20][21] For example, the melting points of the trivalent lanthanides (all but europium and ytterbium) are related to the extent of hybridisation of the 6s, 5d, and 4f electrons (lowering with increasing 4f involvement),[22] and lanthanum has the second-lowest melting point among them: 920 °C. (Europium and ytterbium have lower melting points because they delocalise about two electrons per atom rather than three.)[23] This chemical availability of f orbitals justifies lanthanum's placement in the f-block despite its anomalous ground-state configuration[24][25] (which is merely the result of strong interelectronic repulsion making it less profitable to occupy the 4f shell, as it is small and close to the core electrons).[26]

The lanthanides become harder as the series is traversed: as expected, lanthanum is a soft metal. Lanthanum has a relatively high resistivity of 615 nΩm at room temperature; in comparison, the value for the good conductor aluminium is only 26.50 nΩm.[27][28] Lanthanum is the least volatile of the lanthanides.[29] Like most of the lanthanides, lanthanum has a hexagonal crystal structure at room temperature (α-La). At 310 °C, lanthanum changes to a face-centered cubic structure (β-La), and at 865 °C, it changes to a body-centered cubic structure (γ-La).[28]

Chemical

[edit]As expected from periodic trends, lanthanum has the largest atomic radius of the lanthanides. Hence, it is the most reactive among them, tarnishing quite rapidly in air, turning completely dark after several hours and can readily burn to form lanthanum(III) oxide, La

2O

3, which is almost as basic as calcium oxide.[30] A centimeter-sized sample of lanthanum will corrode completely in a year as its oxide spalls off like iron rust, instead of forming a protective oxide coating like aluminium, scandium, yttrium, and lutetium.[31] Lanthanum reacts with the halogens at room temperature to form the trihalides, and upon warming will form binary compounds with the nonmetals nitrogen, carbon, sulfur, phosphorus, boron, selenium, silicon and arsenic.[15][16] Lanthanum reacts slowly with water to form lanthanum(III) hydroxide, La(OH)

3.[32] In dilute sulfuric acid, lanthanum readily forms the aquated tripositive ion [La(H

2O)

9]3+

: This is colorless in aqueous solution since La3+

has no d or f electrons.[32] Lanthanum is the strongest and hardest base among the rare earth elements, which is again expected from its being the largest of them.[33]

Some lanthanum(II) compounds are also known, but they are much less stable.[16] Therefore, in officially naming compounds of lanthanum its oxidation number always is to be mentioned.

Isotopes

[edit]

Naturally occurring lanthanum is made up of two isotopes, the stable 139

La and the primordial long-lived radioisotope 138

La. 139

La is by far the most abundant, making up 99.910% of natural lanthanum: it is produced in the s-process (slow neutron capture, which occurs in low- to medium-mass stars) and the r-process (rapid neutron capture, which occurs in core-collapse supernovae). It is the only stable isotope of lanthanum.[34] The very rare isotope 138

La is one of the few primordial odd–odd nuclei, with a long half-life of 1.05×1011 years. It is one of the proton-rich p-nuclei which cannot be produced in the s- or r-processes. 138

La, along with the even rarer 180

Ta, is produced in the ν-process, where neutrinos interact with stable nuclei.[35] All other lanthanum isotopes are synthetic: With the exception of 137

La with a half-life of about 60,000 years, all of them have half-lives less than two days, and most have half-lives less than a minute. The isotopes 139

La and 140

La occur as fission products of uranium.[34]

Compounds

[edit]Lanthanum oxide is a white solid that can be prepared by direct reaction of its constituent elements. Due to the large size of the La3+

ion, La

2O

3 adopts a hexagonal 7-coordinate structure that changes to the 6-coordinate structure of scandium oxide (Sc

2O

3) and yttrium oxide (Y

2O

3) at high temperature. When it reacts with water, lanthanum hydroxide is formed:[36] a lot of heat is evolved in the reaction and a hissing sound is heard. Lanthanum hydroxide will react with atmospheric carbon dioxide to form the basic carbonate.[37]

Lanthanum fluoride is insoluble in water and can be used as a qualitative test for the presence of La3+

. The heavier halides are all very soluble deliquescent compounds. The anhydrous halides are produced by direct reaction of their elements, as heating the hydrates causes hydrolysis: for example, heating hydrated LaCl

3 produces LaOCl.[37]

Lanthanum reacts exothermically with hydrogen to produce the dihydride LaH

2, a black, pyrophoric, brittle, conducting compound with the calcium fluoride structure.[38] This is a non-stoichiometric compound, and further absorption of hydrogen is possible, with a concomitant loss of electrical conductivity, until the more salt-like LaH

3 is reached. Like LaI

2 and LaI, LaH

2 is probably an electride compound.[37]

Due to the large ionic radius and great electropositivity of La3+

, there is not much covalent contribution to its bonding and hence it has a limited coordination chemistry, like yttrium and the other lanthanides.[39] Lanthanum oxalate does not dissolve very much in alkali-metal oxalate solutions, and [La(acac)

3(H

2O)

2] decomposes around 500 °C. Oxygen is the most common donor atom in lanthanum complexes, which are mostly ionic and often have high coordination numbers over 6 : 8 is the most characteristic, forming square antiprismatic and dodecadeltahedral structures. These high-coordinate species, reaching up to coordination number 12 with the use of chelating ligands such as in La

2(SO

4)

3· 9(H

2O), often have a low degree of symmetry because of stereo-chemical factors.[39]

Lanthanum chemistry tends not to involve π-bonding due to the electron configuration of the element: thus its organometallic chemistry is quite limited. The best characterized organolanthanum compounds are the cyclopentadienyl complex La(C

5H

5)

3, which is produced by reacting anhydrous LaCl

3 with NaC

5H

5 in tetrahydrofuran, and its methyl-substituted derivatives.[40]

History

[edit]

In 1751, the Swedish mineralogist Axel Fredrik Cronstedt discovered a heavy mineral from the mine at Bastnäs, later named cerite. Thirty years later, the fifteen-year-old Wilhelm Hisinger, from the family owning the mine, sent a sample of it to Carl Scheele, who did not find any new elements within. In 1803, after Hisinger had become an ironmaster, he returned to the mineral with Jöns Jacob Berzelius and isolated a new oxide which they named ceria after the dwarf planet Ceres, which had been discovered two years earlier.[41] Ceria was simultaneously independently isolated in Germany by Martin Heinrich Klaproth.[42] Between 1839 and 1843, ceria was shown to be a mixture of oxides by the Swedish surgeon and chemist Carl Gustaf Mosander, who lived in the same house as Berzelius and studied under him: he separated out two other oxides which he named lanthana and didymia.[43][44] He partially decomposed a sample of cerium nitrate by roasting it in air and then treating the resulting oxide with dilute nitric acid.[b][46] That same year, Axel Erdmann, a student also at the Karolinska Institute, discovered lanthanum in a new mineral from Låven island located in a Norwegian fjord.

Finally, Mosander explained his delay, saying that he had extracted a second element from cerium, and this he called didymium. Although he did not realise it, didymium too was a mixture, and in 1885 it was separated into praseodymium and neodymium.

Since lanthanum's properties differed only slightly from those of cerium, and occurred along with it in its salts, he named it from the Ancient Greek λανθάνειν [lanthanein] (lit. to lie hidden).[42] Relatively pure lanthanum metal was first isolated in 1923.[16]

Occurrence and production

[edit]Lanthanum makes up 39 mg/kg of the Earth's crust,[47][48] behind neodymium at 41.5 mg/kg and cerium at 66.5 mg/kg. Despite being among the so-called "rare earth metals", lanthanum is thus not rare at all, but it is historically so-named because it is rarer than "common earths" such as lime and magnesia, and at the time it was recognized only a few deposits were known. Lanthanum is also ruefully considered a 'rare earth' metal because the process to mine it is difficult, time-consuming, and expensive.[16] Lanthanum is rarely the dominant lanthanide found in the rare earth minerals, and in their chemical formulae it is usually preceded by cerium. Rare examples of La-dominant minerals are monazite-(La) and lanthanite-(La).[49]

The La3+

ion is similarly sized to the early lanthanides of the cerium group (those up to samarium and europium) that immediately follow in the periodic table, and hence it tends to occur along with them in phosphate, silicate and carbonate minerals, such as monazite (MIIIPO4) and bastnäsite (MIIICO3F), where M refers to all the rare earth metals except scandium and the radioactive promethium (mostly Ce, La, and Y).[50] Bastnäsite is usually lacking in thorium and the heavy lanthanides, and the purification of the light lanthanides from it is less involved. The ore, after being crushed and ground, is first treated with hot concentrated sulfuric acid, evolving carbon dioxide, hydrogen fluoride, and silicon tetrafluoride: the product is then dried and leached with water, leaving the early lanthanide ions, including lanthanum, in solution.[51]

The procedure for monazite, which usually contains all the rare earths as well as thorium, is more involved. Monazite, because of its magnetic properties, can be separated by repeated electromagnetic separation. After separation, it is treated with hot concentrated sulfuric acid to produce water-soluble sulfates of rare earths. The acidic filtrates are partially neutralized with sodium hydroxide to pH 3–4. Thorium precipitates out of solution as hydroxide and is removed. After that, the solution is treated with ammonium oxalate to convert rare earths to their insoluble oxalates. The oxalates are converted to oxides by annealing. The oxides are dissolved in nitric acid that excludes one of the main components, cerium, whose oxide is insoluble in HNO

3. Lanthanum is separated as a double salt with ammonium nitrate by crystallization. This salt is relatively less soluble than other rare earth double salts and therefore stays in the residue.[16] Care must be taken when handling some of the residues as they contain 228

Ra, the daughter of 232

Th, which is a strong gamma emitter. Lanthanum is relatively easy to extract as it has only one neighbouring lanthanide, cerium, which can be removed by making use of its ability to be oxidised to the +4 state; thereafter, lanthanum may be separated out by the historical method of fractional crystallization of La(NO

3)

3· 2 NH

4NO

3· 4 H

2O, or by ion-exchange techniques when higher purity is desired.[51]

Lanthanum metal is obtained from its oxide by heating it with ammonium chloride or fluoride and hydrofluoric acid at 300–400 °C to produce the chloride or fluoride:[16]

- La

2O

3 + 6 NH

4Cl → 2 LaCl

3 + 6 NH

3 + 3 H

2O

This is followed by reduction with alkali or alkaline earth metals in vacuum or argon atmosphere:[16]

- LaCl

3 + 3 Li → La + 3 LiCl

Also, pure lanthanum can be produced by electrolysis of molten mixture of anhydrous LaCl

3 and NaCl or KCl at elevated temperatures.[16]

Applications

[edit]

The first historical application of lanthanum was in gas lantern mantles. Carl Auer von Welsbach used a mixture of lanthanum oxide and zirconium oxide, which he called Actinophor and patented in 1886. The original mantles gave a green-tinted light and were not very successful, and his first company, which established a factory in Atzgersdorf in 1887, failed in 1889.[52]

Modern uses of lanthanum include:

6 hot cathode

- One material used for anodic material of nickel–metal hydride batteries is La(Ni

3.6Mn

0.4Al

0.3Co

0.7). Due to high cost to extract the other lanthanides, a mischmetal with more than 50% of lanthanum is used instead of pure lanthanum. The compound is an intermetallic component of the AB

5 type.[53][54] NiMH batteries can be found in many models of the Toyota Prius sold in the US. These larger nickel-metal hydride batteries require massive quantities of lanthanum for the production. The 2008 Toyota Prius NiMH battery requires 10 to 15 kilograms (22 to 33 lb) of lanthanum. As engineers push the technology to increase fuel efficiency, twice that amount of lanthanum could be required per vehicle.[55][56][57] - Hydrogen sponge alloys can contain lanthanum. These alloys are capable of storing up to 400 times their own volume of hydrogen gas in a reversible adsorption process. Heat energy is released every time they do so; therefore these alloys have possibilities in energy conservation systems.[28][58]

- Mischmetal, a pyrophoric alloy used in lighter flints, contains 25% to 45% lanthanum.[59]

- Lanthanum oxide and the boride are used in electronic vacuum tubes as hot cathode materials with strong emissivity of electrons. Crystals of LaB

6 are used in high-brightness, extended-life, thermionic electron emission sources for electron microscopes and Hall-effect thrusters.[60] - Lanthanum trifluoride (LaF

3) is an essential component of a heavy fluoride glass named ZBLAN. This glass has superior transmittance in the infrared range and is therefore used for fiber-optical communication systems.[61] - Cerium-doped lanthanum bromide and lanthanum chloride are the recent inorganic scintillators, which have a combination of high light yield, best energy resolution, and fast response. Their high yield converts into superior energy resolution; moreover, the light output is very stable and quite high over a very wide range of temperatures, making it particularly attractive for high-temperature applications. These scintillators are already widely used commercially in detectors of neutrons or gamma rays.[62]

- Carbon arc lamps use a mixture of rare earth elements to improve the light quality. This application, especially by the motion picture industry for studio lighting and projection, consumed about 25% of the rare-earth compounds produced until the phase out of carbon arc lamps.[28][63]

- Lanthanum(III) oxide (La

2O

3) improves the alkali resistance of glass and is used in making special optical glasses, such as infrared-absorbing glass, as well as camera and telescope lenses, because of the high refractive index and low dispersion of rare-earth glasses.[28] Lanthanum oxide is also used as a grain-growth additive during the liquid-phase sintering of silicon nitride and zirconium diboride.[64] - Small amounts of lanthanum added to steel improves its malleability, resistance to impact, and ductility, whereas addition of lanthanum to molybdenum decreases its hardness and sensitivity to temperature variations.[28]

- Small amounts of lanthanum are present in many pool products to remove the phosphates that feed algae.[65]

- Lanthanum oxide additive to tungsten is used in gas tungsten arc welding electrodes, as a substitute for radioactive thorium.[66][67]

- Various compounds of lanthanum and other rare-earth elements (oxides, chlorides, triflates, etc.) are components of various catalysis, such as petroleum cracking catalysts.[68]

- Lanthanum-barium radiometric dating is used to estimate age of rocks and ores, though the technique has limited popularity.[69]

- Lanthanum carbonate was approved as a medication (Fosrenol, Shire Pharmaceuticals) to absorb excess phosphate in cases of hyperphosphatemia seen in end-stage kidney disease.[70]

- Lanthanum fluoride is used in phosphor lamp coatings. Mixed with europium fluoride, it is also applied in the crystal membrane of fluoride ion-selective electrodes.[16]

- Like horseradish peroxidase, lanthanum is used as an electron-dense tracer in molecular biology.[71]

- Lanthanum-modified bentonite (or phoslock) is used to remove phosphates from water in lake treatments.[72]

- Lanthanum telluride (La

3Te

4) is considered to be applied in the field of radioisotope power system (nuclear power plant) due to its significant conversion capabilities. The transmuted elements and isotopes in the segment will not react with the material itself, thus presenting no harm to the safety of the power plant. Though iodine, which can be generated during transmutation, is suspected to react with La

3Te

4 segment, the quantity of iodine is small enough to pose no threat to the power system.[73]

Biological role

[edit]Lanthanum has no known biological role in humans. The element is very poorly absorbed after oral administration and when injected its elimination is very slow. Lanthanum carbonate (Fosrenol) was approved as a phosphate binder to absorb excess phosphate in cases of end stage renal disease.[70]

While lanthanum has pharmacological effects on several receptors and ion channels, its specificity for the GABA receptor is unique among trivalent cations. Lanthanum acts at the same modulatory site on the GABA receptor as zinc, a known negative allosteric modulator. The lanthanum cation La3+

is a positive allosteric modulator at native and recombinant GABA receptors, increasing open channel time and decreasing desensitization in a subunit configuration dependent manner.[74]

Lanthanum is an essential cofactor for the methanol dehydrogenase of the methanotrophic bacterium Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV, although the great chemical similarity of the lanthanides means that it may be substituted with cerium, praseodymium, or neodymium without ill effects, and with the smaller samarium, europium, or gadolinium giving no side effects other than slower growth.[75]

Precautions

[edit]| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H260 | |

| P223, P231+P232, P370+P378, P422[76] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Lanthanum has a low to moderate level of toxicity and should be handled with care. The injection of lanthanum solutions produces hyperglycemia, low blood pressure, degeneration of the spleen and hepatic alterations.[citation needed] The application in carbon arc light led to the exposure of people to rare earth element oxides and fluorides, which sometimes led to pneumoconiosis.[77][78] As the La3+

ion is similar in size to the Ca2+

ion, it is sometimes used as an easily traced substitute for the latter in medical studies.[79] Lanthanum, like the other lanthanides, is known to affect human metabolism, lowering cholesterol levels, blood pressure, appetite, and risk of blood coagulation. When injected into the brain, it acts as a painkiller, similarly to morphine and other opiates, though the mechanism behind this is still unknown.[79] Lanthanum meant for ingestion, typically as a chewable tablet or oral powder, can interfere with gastrointestinal (GI) imaging by creating opacities throughout the GI tract; if chewable tablets are swallowed whole, they will dissolve but present initially as coin-shaped opacities in the stomach, potentially confused with ingested metal objects such as coins or batteries.[80]

Prices

[edit]The price for a (metric) ton [1000 kg] of Lanthanum oxide 99% (FOB China in USD/Mt) is given by the Institute of Rare Earths Elements and Strategic Metals (IREESM) as below $2,000 for most of the period from early 2001 to September 2010 (at $10,000 in the short term in 2008); it rose steeply to $140,000 in mid-2011 and fell back just as rapidly to $38,000 by early 2012.[81] The average price for the last six months (April–September 2022) is given by the IREESM as follows: Lanthanum Oxide - 99.9%min FOB China - 1308 EUR/mt and for Lanthanum Metal - 99%min FOB China - 3706 EUR/mt.[82]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The thermal expansion of α-La is anisotropic: the parameters (at 20 °C) for each crystal axis are αa = 2.9×10−6/K, αc = 9.5×10−6/K, and αaverage = αV/3 = 5.1×10−6/K.[3]

- ^

From Berzelius (1839a), p. 356:

- "L'oxide de cérium, extrait de la cérite par la procédé ordinaire, contient à peu près les deux cinquièmes de son poids de l'oxide du nouveau métal qui ne change que peu les propriétés du cérium, et qui s'y tient pour ainsi dire caché. Cette raison a engagé M. Mosander à donner au nouveau métal le nom de Lantane."

- [ The oxide of cerium, extracted from cerite by the usual procedure, contains almost two fifths of its weight in the oxide of the new metal, which differs only slightly from the properties of cerium, and which is held in it so to speak "hidden". This reason motivated Mr. Mosander to give to the new metal the name Lantane. ][45]

- "L'oxide de cérium, extrait de la cérite par la procédé ordinaire, contient à peu près les deux cinquièmes de son poids de l'oxide du nouveau métal qui ne change que peu les propriétés du cérium, et qui s'y tient pour ainsi dire caché. Cette raison a engagé M. Mosander à donner au nouveau métal le nom de Lantane."

References

[edit]- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Lanthanum". CIAAW. 2005.

- ^ Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (4 May 2022). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ a b c d Arblaster, John W. (2018). Selected Values of the Crystallographic Properties of Elements. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ^ Yttrium and all lanthanides except Ce and Pm have been observed in the oxidation state 0 in bis(1,3,5-tri-t-butylbenzene) complexes, see Cloke, F. Geoffrey N. (1993). "Zero Oxidation State Compounds of Scandium, Yttrium, and the Lanthanides". Chem. Soc. Rev. 22: 17–24. doi:10.1039/CS9932200017. and Arnold, Polly L.; Petrukhina, Marina A.; Bochenkov, Vladimir E.; Shabatina, Tatyana I.; Zagorskii, Vyacheslav V.; Cloke (15 December 2003). "Arene complexation of Sm, Eu, Tm and Yb atoms: a variable temperature spectroscopic investigation". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 688 (1–2): 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2003.08.028.

- ^ La(I), Pr(I), Tb(I), Tm(I), and Yb(I) have been observed in MB8− clusters; see Li, Wan-Lu; Chen, Teng-Teng; Chen, Wei-Jia; Li, Jun; Wang, Lai-Sheng (2021). "Monovalent lanthanide(I) in borozene complexes". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 6467. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26785-9. PMC 8578558. PMID 34753931.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). "Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (PDF) (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ "Monazite-(Ce) Mineral Data". Webmineral. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ Fluck, E. (1988). "New notations in the periodic table" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 60 (3): 431–436. doi:10.1351/pac198860030431. S2CID 96704008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. (1958). Quantum Mechanics: Non-relativistic theory. Vol. 3 (1st ed.). Pergamon Press. pp. 256–257.

- ^ Jensen, W.B. (1982). "The positions of lanthanum (actinium) and lutetium (lawrencium) in the periodic table". Journal of Chemical Education. 59 (8): 634–636. Bibcode:1982JChEd..59..634J. doi:10.1021/ed059p634.

- ^ Jensen, William B. (2015). "The positions of lanthanum (actinium) and lutetium (lawrencium) in the periodic table: An update". Foundations of Chemistry. 17: 23–31. doi:10.1007/s10698-015-9216-1. S2CID 98624395. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Scerri, Eric (18 January 2021). "Provisional report on discussions on group 3 of the periodic table". Chemistry International. 43 (1): 31–34. doi:10.1515/ci-2021-0115. S2CID 231694898.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw (1984), p. 1106

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Patnaik, Pradyot (2003). Handbook of Inorganic Chemical Compounds. McGraw-Hill. pp. 444–446. ISBN 978-0-07-049439-8. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ Hitchcock, Peter B.; Lappert, Michael F.; Maron, Laurent; Protchenko, Andrey V. (2008). "Lanthanum Does Form Stable Molecular Compounds in the +2 Oxidation State". Angewandte Chemie. 120 (8): 1510. Bibcode:2008AngCh.120.1510H. doi:10.1002/ange.200704887.

- ^ Jevons, W. (1928). "The band spectrum of lanthanum monoxide". Proceedings of the Physical Society. 41 (1): 520. Bibcode:1928PPS....41..520J. doi:10.1088/0959-5309/41/1/355.

- ^ Cullity, B.D.; Graham, C.D. (2011). Introduction to Magnetic Materials. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118211496.

- ^ Wittig, Jörg (19–24 March 1973). "The pressure variable in solid state physics: What about 4f-band superconductors?". Written at Münster, DE. In Queisser, H.J. (ed.). Festkörper Probleme (plenary lecture) [Solid state problems (plenary lecture)]. The Divisions Semiconductor Physics, Surface Physics, Low Temperature Physics, High Polymers, Thermodynamics and Statistical Mechanics, of the German Physical Society. Advances in Solid State Physics (in German). Vol. 13. Berlin, DE / Heidelberg, DE: Springer. pp. 375–396. doi:10.1007/BFb0108579. ISBN 978-3-528-08019-8.

- ^ Krinsky, Jamin L.; Minasian, Stefan G.; Arnold, John (8 December 2010). "Covalent lanthanide chemistry near the limit of weak bonding: Observation of (CpSiMe

3)

3Ce−ECp* and a comprehensive density functional theory analysis of Cp

3Ln−ECp (E = Al, Ga)". Inorganic Chemistry. 50 (1). American Chemical Society (ACS): 345–357. doi:10.1021/ic102028d. ISSN 0020-1669. PMID 21141834. - ^ Gschneidner, Karl A., Jr. (2016). "282 Systematics". In Bünzli, Jean-Claude G.; Vitalij K. Pecharsky (eds.). Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Vol. 50. pp. 12–16. ISBN 978-0-444-63851-9.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krishnamurthy, Nagaiyar; Gupta, Chiranjib Kumar (2004). Extractive Metallurgy of Rare Earths. CRC Press. ISBN 0-415-33340-7.

- ^ Hamilton, David C. (1965). "Position of lanthanum in the periodic table". American Journal of Physics. 33 (8): 637–640. Bibcode:1965AmJPh..33..637H. doi:10.1119/1.1972042.

- ^ Jensen, W.B. (2015). Some comments on the position of lawrencium in the periodic table (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ Jørgensen, Christian (1973). "The Loose Connection between Electron Configuration and the Chemical Behavior of the Heavy Elements (Transuranics)". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 12 (1): 12–19. doi:10.1002/anie.197300121.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw (1984), p. 1429

- ^ a b c d e f Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ The Radiochemistry of the Rare Earths, Scandium, Yttrium, and Actinium (PDF) (Report). Los Alamos, NM: Los Alamos National Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2016 – via lanl.gov.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw (1984), pp. 1105–1107

- ^ "Rare-Earth Metal Long Term Air Exposure Test". Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Chemical reactions of lanthanum". Webelements. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw (1984), p. 1434

- ^ a b Audi, Georges; Bersillon, Olivier; Blachot, Jean; Wapstra, Aaldert Hendrik (2003), "The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties", Nuclear Physics A, 729: 3–128, Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A, doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001

- ^ Woosley, S.E.; Hartmann, D.H.; Hoffman, R.D.; Haxton, W.C. (1990). "The ν-process". The Astrophysical Journal. 356: 272–301. Bibcode:1990ApJ...356..272W. doi:10.1086/168839.

- ^ Shkolnikov, E.V. (2009). "Thermodynamic characterization of the amphoterism of hydroxides and oxides of scandium subgroup elements in aqueous media". Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry. 82 (2): 2098–2104. doi:10.1134/S1070427209120040. S2CID 93220420.

- ^ a b c Greenwood & Earnshaw (1984), pp. 1107–1108

- ^ Fukai, Y. (2005). The Metal-Hydrogen System, Basic Bulk Properties (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-00494-3.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw (1984), pp. 1108–1109

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw (1984), p. 1110

- ^ "The Discovery and Naming of the Rare Earths". Elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw (1984), p. 1424

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1956). The discovery of the elements (6th ed.). Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements: XI. Some elements isolated with the aid of potassium and sodium: Zirconium, titanium, cerium, and thorium". The Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (7): 1231–1243. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9.1231W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1231.

- ^ Berzelius (1839a). "Nouveau métal" [New metal]. Comptes rendus (in French). 8: 356–357, quote p 356 – via Google books.

- ^ Berzelius (1839b). "Latanium — a new metal". Philosophical Magazine. new series. Vol. 14. pp. 390–391. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022.

- ^ "It's elemental — the periodic table of elements". Education. jlab.org. Newport News, VA: Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility. Archived from the original on 29 April 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ^ "Abundance of elements in the Earth's crust and in the sea". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). 2016–2017. p. 14.

- ^ "Mindat.org". mindat.org. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. 1993–2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw (1984), p. 1103

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw (1984), pp. 1426–1429

- ^ Evans, C.H., ed. (6 December 2012). Episodes from the History of the Rare Earth Elements. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 122. ISBN 9789400902879.

- ^ "Inside the Nickel Metal Hydride Battery" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ Tliha, M.; Mathlouthi, H.; Lamloumi, J.; Percheronguegan, A. (2007). "AB5-type hydrogen storage alloy used as anodic materials in Ni-MH batteries". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 436 (1–2): 221–225. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2006.07.012.

- ^ "As hybrid cars gobble rare metals, shortage looms". Reuters 2009-08-31. 31 August 2009.

- ^ Bauerlein, P.; Antonius, C.; Loffler, J.; Kumpers, J. (2008). "Progress in high-power nickel–metal hydride batteries". Journal of Power Sources. 176 (2): 547. Bibcode:2008JPS...176..547B. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.08.052.

- ^ "Why Toyota offers 2 battery choices in next Prius". 19 November 2015.

- ^ Uchida, H. (1999). "Hydrogen solubility in rare earth based hydrogen storage alloys". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 24 (9): 871–877. Bibcode:1999IJHE...24..871U. doi:10.1016/S0360-3199(98)00161-X.

- ^ Hammond, C.R. (2000). "The Elements". Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (81st ed.). CRC press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0481-1.

- ^ Sommerville, Jason D. & King, Lyon B. "Effect of Cathode Position on Hall-Effect Thruster Performance and Cathode Coupling Voltage" (PDF). 43rd AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, 8–11 July 2007, Cincinnati, OH. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ Harrington, James A. Infrared fiber optics (PDF) (Report). Rutgers University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2010.

- ^ "BrilLanCe-NxGen" (PDF). Detectors. oilandgas.saint-gobain.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ Hendrick, James B. (1985). "Rare Earth Elements and Yttrium". Mineral Facts and Problems (Report). Bureau of Mines. p. 655. Bulletin 675.

- ^ Kim, K; Shim, Kwang Bo (2003). "The effect of lanthanum on the fabrication of ZrB2–ZrC composites by spark plasma sintering". Materials Characterization. 50: 31–37. doi:10.1016/S1044-5803(03)00055-X.

- ^ Pool Care Basics. pp. 25–26.

- ^ Cary, Howard B. (1995). Arc Welding Automation. CRC Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8247-9645-7.

- ^ Jeffus, Larry (2003). "Types of Tungsten". Welding : Principles and applications. Clifton Park, N.Y.: Thomson/Delmar Learning. p. 350. ISBN 978-1-4018-1046-7. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010.

- ^ C. K. Gupta; Nagaiyar Krishnamurthy (2004). Extractive metallurgy of rare earths. CRC Press. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-415-33340-5.

- ^ S. Nakai; A. Masuda; B. Lehmann (1988). "La-Ba dating of bastnaesite" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 7 (1–2): 1111. Bibcode:1988ChGeo..70...12N. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(88)90211-2.

- ^ a b "FDA approves Fosrenol(R) in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients". 28 October 2004. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ Chau YP; Lu KS (1995). "Investigation of the blood-ganglion barrier properties in rat sympathetic ganglia by using lanthanum ion and horseradish peroxidase as tracers". Acta Anatomica. 153 (2): 135–144. doi:10.1159/000313647. ISSN 0001-5180. PMID 8560966.

- ^ Hagheseresht; Wang, Shaobin; Do, D. D. (2009). "A novel lanthanum-modified bentonite, Phoslock, for phosphate removal from wastewaters". Applied Clay Science. 46 (4): 369–375. Bibcode:2009ApCS...46..369H. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2009.09.009.

- ^ R. Smith, Michael B.; Whiting, Christopher; Barklay, Chad (2019). "Nuclear Considerations for the Application of Lanthanum Telluride in Future Radioisotope Power Systems". 2019 IEEE Aerospace Conference. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1109/AERO.2019.8742136. ISBN 978-1-5386-6854-2. OSTI 1542236. S2CID 195221607.

- ^ Boldyreva, A.A. (2005). "Lanthanum potentiates GABA-activated currents in rat pyramidal neurons of CA1 hippocampal field". Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine. 140 (4): 403–5. doi:10.1007/s10517-005-0503-z. PMID 16671565. S2CID 13179025.

- ^ Pol, Arjan; Barends, Thomas R.M.; Dietl, Andreas; Khadem, Ahmad F.; Eygensteyn, Jelle; Jetten, Mike S. M.; Op Den Camp, Huub J. M. (2013). "Rare earth metals are essential for methanotrophic life in volcanic mudpots" (PDF). Environmental Microbiology. 16 (1): 255–64. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12249. PMID 24034209.

- ^ "Lanthanum 261130". Sigma-Aldrich.

- ^ Dufresne, A.; Krier, G.; Muller, J.; Case, B.; Perrault, G. (1994). "Lanthanide particles in the lung of a printer". Science of the Total Environment. 151 (3): 249–252. Bibcode:1994ScTEn.151..249D. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(94)90474-X. PMID 8085148.

- ^ Waring, P.M.; Watling, R.J. (1990). "Rare earth deposits in a deceased movie projectionist. A new case of rare earth pneumoconiosis". The Medical Journal of Australia. 153 (11–12): 726–30. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb126334.x. PMID 2247001. S2CID 24985591.

- ^ a b Emsley, John (2011). Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z guide to the elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 266–77. ISBN 9780199605637.

- ^ Evans NS, Aronowitz P, Altertson TE (30 October 2023). "Coin-shaped opacities in the stomach". JAMA Clinical Challenge. Journal of the American Medical Association. 330 (20): 2016–2017. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.19032. PMID 37902730. S2CID 264589220.

- ^ "Lanthanum". institut-seltene-erden.de. Retrieved 27 October 2022. — site gives specifications and notation

- ^ "ISE Metal-quotes". institut-seltene-erden.de. Retrieved 27 October 2022. — site gives information and notation

Bibliography

[edit]- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford: Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-022057-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Callow, R.J. (1967). The Industrial Chemistry of the Lanthanons, Yttrium, Thorium and Uranium. Pergamon Press.

- Gupta, C.K.; Krishnamurthy, N. (2005). Extractive Metallurgy of Rare Earths. CRC Press.

- Pascal, P., ed. (1959). Nouveau Traité de Chimie Minérale [New Treatise on Mineral Chemistry] (in French). Vol. VII Scandium, Yttrium, Elements des Terres Rares, Actinium. Masson & Cie.

- Vickery, R.C. (1953). Chemistry of the Lanthanons. Butterworths.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||