Djudios Paradesi | |

|---|---|

Portrait of David Henriques De Castro, by Gabriel Haim Henriques De Castro (1838-1897) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 700 | |

| 52[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Initially Ladino, later Judeo-Malayalam, Tamil, now mostly Hebrew and English | |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Spanish and Portuguese Jews Sephardic Jews in India De Castro family Henriques family Cochin Jews Indian Jews Desi Jews | |

Paradesi Jews refer to Jewish immigrants to the Indian subcontinent during the 15th and 16th centuries following the expulsion of Jews from Spain and Portugal. Paradesi means foreign in Malayalam and Tamil.[2] These Sephardic immigrants fled persecution and death by burning in the wake of the 1492 Alhambra Decree and King Manuel's 1496 decree expelling Jews from Portugal. They are sometimes referred to as "White Jews", although that usage is generally considered pejorative or discriminatory and refers to relatively recent Jewish immigrants (end of the 15th century onward), predominantly Sephardim.[3]

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Paradesi Jews were Sephardi immigrants to the Indian subcontinent from Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries[4][5] fleeing forcible conversion, persecution, and antisemitism. The Paradesi Jews of Cochin traded in spices. They are a community of Sephardic Jews settled among the larger Cochin Jewish community located in Kerala, a coastal southern state of India.[3]

Paradesi Jews of Madras (now Chennai) traded in Golconda diamonds, precious stones, and corals. They had very good relations with the rulers of Golkonda because they maintained trade connections to some foreign countries (e.g. Ottoman empire, Europe), and their language skills were useful. Although the Sephardim spoke Ladino (i.e. Judeo-Spanish), in India they learned Tamil and Konkani as well as Judeo-Malayalam from the Cochin Jews, also known as Malabar Jews.[6][full citation needed]

After India gained its independence in 1947 and Israel was established as a nation, most of the Malabar Jews made Aliyah and emigrated from Kerala to Israel in the mid-1950s. In contrast, most of the Paradesi Jews preferred to migrate to Australia and other Commonwealth countries, similar to the choices made by Anglo-Indians.[7]

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

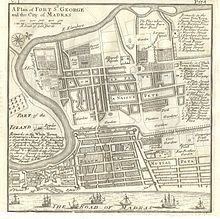

The East India Company (EIC) wanted to break the monopoly of Portugal in trading with Golconda diamonds and precious stones from the mines of Golkonda. The EIC entered India around 1600 and had built the Fort St. George (White Town) fortress by 1644[8][full citation needed] at the coastal city of Madras, now known as Chennai.

EIC policy permitted only its shareholders to trade in Golconda diamonds and precious stones from the mines. The Company considered the Madras Jews to be interlopers because they traded separately through their Jewish community connections.[9]

Madras Jews specialised in Golconda diamonds, precious stones, and corals.[10] They had very good relations with the rulers of Golkonda and this was seen as beneficial to Fort St. George, so Madras Jews were gradually accepted as honourable citizens of Fort St. George/Madras.[11][need quotation to verify]

Jacques de Paiva (Jaime Paiva), originally from Amsterdam and belonging to Amsterdam Sephardic community, was an early Jewish arrival and the leader of Madras Jewish community. He built the Second Madras Synagogue and Jewish Cemetery Chennai in Peddanaickenpet, which later became the South end of Mint Street.[12][13]

de Paiva died in 1687 after a visit to his Golconda diamond mines and was buried in the Jewish cemetery which he had established,[13] alongside the synagogue which also existed at Mint Street.[14]

After de Paiva's death in 1687, his wife Hieronima de Paiva fell in love with Elihu Yale, Governor of Madras, and went to live with him, causing quite a scandal within Madras' colonial society. Governor Elihu Yale later achieved fame when he gave a large donation to the University of New Haven in Connecticut, which was then named after him — the Yale University. Elihu Yale and Hieromima de Paiva had a son, who died in South Africa.[15]

In 1670, the Portuguese population in Madras numbered around 3,000.[citation needed] Before his death, de Paiva established 'The Colony of Jewish Traders of Madraspatam' with Antonio do Porto, Pedro Pereira, and Fernando Mendes Henriques.[13] This enabled more Portuguese Jews from Leghorn, the Caribbean, London, and Amsterdam to settle in Madras.[citation needed] Coral Merchant Street was named after the Jews' business.[16]

Three Portuguese Jews were nominated to be aldermen of Madras Corporation.[17] Three - Bartolomeo Rodrigues, Domingo do Porto, and Alvaro da Fonseca - also founded the largest trading house in Madras. The large tomb of Rodrigues, who died in Madras in 1692, became a landmark in Peddanaickenpet but was later destroyed.[18]

Samuel de Castro came to Madras from Curaçao in 1766 and Salomon Franco came from Leghorn.[13][19]

Isaac Sardo Abendana (1662–1709), who came from Holland, died in Madras. He was a close friend of Thomas Pitt and may have been responsible for the fortune that Pitt amassed.[13]

Portuguese Jews were used as diplomats by the East India Company to expand English trading. Avraham Navarro was the most prominent of these.[20]

In 1688, the famous Sephardi poet Daniel Levy de Barrios wrote a poem in Amsterdam, with historical and geographical meaning. His information was usually most precise and drawing upon him we may receive a panorama of Sephardi life in the seventeenth century. There were six Jewish communities — Nieves, London, Jamaica, fourth and fifth in two parts of Barbados, and the sixth in Madras-Patan.[21][22]

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Yemenite Jews started coming to Madras via Cochin. They were very religious. Some came from Najran. They were Rabbis and jewelry-makers.[12]

From the 19th centuries, Yemenite Jews and Portuguese Jews started intermarrying.[12][21]

The Paradesi Jews had built three Paradesi synagogues and cemeteries.

In 1500, the first Madras Synagogue and cemeteries was built by the Amsterdam Sephardic community in Coral Merchant Street, George Town, Madras, which had a large presence of Portuguese Jews in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Neither the synagogue nor the Jewish population remains today.[23]

In 1568, the first Cochin Paradesi Synagogue and cemetery was built in Cochin-Jew Street, adjacent to Mattancherry Palace, Cochin, now part of the Indian city of Ernakulam, on land given to them by the Raja of Kochi.[24]

In 1644, the second Madras Synagogue and Jewish Cemetery Chennai was built by de Paiva, also from Amsterdam Sephardic community in Madras, Peddanaickenpet, which later became the south end of Mint Street.[13] It was demolished by local government in 1934 and the tombstones were moved to the Central Park of Madras along with the gate of the cemetery on which Beit ha-Haim (the usual designation for a Jewish cemetery, literally "House of Life") were written in Hebrew.[25] The tombstones were moved again in 1979[citation needed] to Kasimedu, when a government school was approved to be built. In 1983, they were moved to Lloyds Road, when the Chennai Harbour expansion project was approved.[14] In this whole process seventeen tombstones went missing, including that of de Paiva.[26]