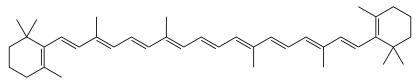

Carotenoids (/kəˈrɒtɪnɔɪd/) are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and fungi.[1] Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, corn, tomatoes, canaries, flamingos, salmon, lobster, shrimp, and daffodils. Over 1,100 identified carotenoids can be further categorized into two classes – xanthophylls (which contain oxygen) and carotenes (which are purely hydrocarbons and contain no oxygen).[2]

All are derivatives of tetraterpenes, meaning that they are produced from 8 isoprene units and contain 40 carbon atoms. In general, carotenoids absorb wavelengths ranging from 400 to 550 nanometers (violet to green light). This causes the compounds to be deeply colored yellow, orange, or red. Carotenoids are the dominant pigment in autumn leaf coloration of about 15-30% of tree species,[3] but many plant colors, especially reds and purples, are due to polyphenols.

Carotenoids serve two key roles in plants and algae: they absorb light energy for use in photosynthesis, and they provide photoprotection via non-photochemical quenching.[4] Carotenoids that contain unsubstituted beta-ionone rings (including β-carotene, α-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, and γ-carotene) have vitamin A activity (meaning that they can be converted to retinol). In the eye, lutein, meso-zeaxanthin, and zeaxanthin are present as macular pigments whose importance in visual function, as of 2016, remains under clinical research.[3][5]

Structure and function

[edit]

Carotenoids are produced by all photosynthetic organisms and are primarily used as accessory pigments to chlorophyll in the light-harvesting part of photosynthesis.

They are highly unsaturated with conjugated double bonds, which enables carotenoids to absorb light of various wavelengths. At the same time, the terminal groups regulate the polarity and properties within lipid membranes.

Most carotenoids are tetraterpenoids, regular isoprenoids. Several modifications to these structures exist: including cyclization, varying degrees of saturation or unsaturation, and other functional groups.[6] Carotenes typically contain only carbon and hydrogen, i.e., they are hydrocarbons. Prominent members include α-carotene, β-carotene, and lycopene, are known as carotenes. Carotenoids containing oxygen include lutein and zeaxanthin. They are known as xanthophylls.[3] Their color, ranging from pale yellow through bright orange to deep red, is directly related to their structure, especially the length of the conjugation.[3] Xanthophylls are often yellow, giving their class name.

Carotenoids also participate in different types of cell signaling.[7] They are able to signal the production of abscisic acid, which regulates plant growth, seed dormancy, embryo maturation and germination, cell division and elongation, floral growth, and stress responses.[8]

Photophysics

[edit]The length of the multiple conjugated double bonds determines their color and photophysics.[9][10] After absorbing a photon, the carotenoid transfers its excited electron to chlorophyll for use in photosynthesis.[9] Upon absorption of light, carotenoids transfer excitation energy to and from chlorophyll. The singlet-singlet energy transfer is a lower energy state transfer and is used during photosynthesis.[7] The triplet-triplet transfer is a higher energy state and is essential in photoprotection.[7] Light produces damaging species during photosynthesis, with the most damaging being reactive oxygen species (ROS). As these high energy ROS are produced in the chlorophyll the energy is transferred to the carotenoid’s polyene tail and undergoes a series of reactions in which electrons are moved between the carotenoid bonds in order to find the most balanced (lowest energy) state for the carotenoid.[9]

Carotenoids defend plants against singlet oxygen, by both energy transfer and by chemical reactions. They also protect plants by quenching triplet chlorophyll.[11] By protecting lipids from free-radical damage, which generate charged lipid peroxides and other oxidised derivatives, carotenoids support crystalline architecture and hydrophobicity of lipoproteins and cellular lipid structures, hence oxygen solubility and its diffusion therein.[12]

Structure-property relationships

[edit]Like some fatty acids, carotenoids are lipophilic due to the presence of long unsaturated aliphatic chains.[3] As a consequence, carotenoids are typically present in plasma lipoproteins and cellular lipid structures.[13]

Morphology

[edit]Carotenoids are located primarily outside the cell nucleus in different cytoplasm organelles, lipid droplets, cytosomes and granules. They have been visualised and quantified by raman spectroscopy in an algal cell.[14]

With the development of monoclonal antibodies to trans-lycopene it was possible to localise this carotenoid in different animal and human cells.[15]

Foods

[edit]Beta-carotene, found in pumpkins, sweet potato, carrots and winter squash, is responsible for their orange-yellow colors.[3] Dried carrots have the highest amount of carotene of any food per 100-gram serving, measured in retinol activity equivalents (provitamin A equivalents).[3][16] Vietnamese gac fruit contains the highest known concentration of the carotenoid lycopene.[17] Although green, kale, spinach, collard greens, and turnip greens contain substantial amounts of beta-carotene.[3] The diet of flamingos is rich in carotenoids, imparting the orange-colored feathers of these birds.[18]

Reviews of preliminary research in 2015 indicated that foods high in carotenoids may reduce the risk of head and neck cancers[19] and prostate cancer.[20] There is no correlation between consumption of foods high in carotenoids and vitamin A and the risk of Parkinson's disease.[21]

Humans and other animals are mostly incapable of synthesizing carotenoids, and must obtain them through their diet. Carotenoids are a common and often ornamental feature in animals. For example, the pink color of salmon, and the red coloring of cooked lobsters and scales of the yellow morph of common wall lizards are due to carotenoids.[22][citation needed] It has been proposed that carotenoids are used in ornamental traits (for extreme examples see puffin birds) because, given their physiological and chemical properties, they can be used as visible indicators of individual health, and hence are used by animals when selecting potential mates.[23]

Carotenoids from the diet are stored in the fatty tissues of animals,[3] and exclusively carnivorous animals obtain the compounds from animal fat. In the human diet, absorption of carotenoids is improved when consumed with fat in a meal.[24] Cooking carotenoid-containing vegetables in oil and shredding the vegetable both increase carotenoid bioavailability.[3][24][25]

Plant colors

[edit]

The most common carotenoids include lycopene and the vitamin A precursor β-carotene. In plants, the xanthophyll lutein is the most abundant carotenoid and its role in preventing age-related eye disease is currently under investigation.[5] Lutein and the other carotenoid pigments found in mature leaves are often not obvious because of the masking presence of chlorophyll. When chlorophyll is not present, as in autumn foliage, the yellows and oranges of the carotenoids are predominant. For the same reason, carotenoid colors often predominate in ripe fruit after being unmasked by the disappearance of chlorophyll.

Carotenoids are responsible for the brilliant yellows and oranges that tint deciduous foliage (such as dying autumn leaves) of certain hardwood species as hickories, ash, maple, yellow poplar, aspen, birch, black cherry, sycamore, cottonwood, sassafras, and alder. Carotenoids are the dominant pigment in autumn leaf coloration of about 15-30% of tree species.[26] However, the reds, the purples, and their blended combinations that decorate autumn foliage usually come from another group of pigments in the cells called anthocyanins. Unlike the carotenoids, these pigments are not present in the leaf throughout the growing season, but are actively produced towards the end of summer.[27]

Bird colors and sexual selection

[edit]Dietary carotenoids and their metabolic derivatives are responsible for bright yellow to red coloration in birds.[28] Studies estimate that around 2956 modern bird species display carotenoid coloration and that the ability to utilize these pigments for external coloration has evolved independently many times throughout avian evolutionary history.[29] Carotenoid coloration exhibits high levels of sexual dimorphism, with adult male birds generally displaying more vibrant coloration than females of the same species.[30]

These differences arise due to the selection of yellow and red coloration in males by female preference.[31][30] In many species of birds, females invest greater time and resources into raising offspring than their male partners. Therefore, it is imperative that female birds carefully select high quality mates. Current literature supports the theory that vibrant carotenoid coloration is correlated with male quality—either though direct effects on immune function and oxidative stress,[32][33][34] or through a connection between carotenoid metabolizing pathways and pathways for cellular respiration.[35][36]

It is generally considered that sexually selected traits, such as carotenoid-based coloration, evolve because they are honest signals of phenotypic and genetic quality. For instance, among males of the bird species Parus major, the more colorfully ornamented males produce sperm that is better protected against oxidative stress due to increased presence of carotenoid antioxidants.[37] However, there is also evidence that attractive male coloration may be a faulty signal of male quality. Among stickleback fish, males that are more attractive to females due to carotenoid colorants appear to under-allocate carotenoids to their germline cells.[38] Since carotinoids are beneficial antioxidants, their under-allocation to germline cells can lead to increased oxidative DNA damage to these cells.[38] Therefore, female sticklebacks may risk fertility and the viability of their offspring by choosing redder, but more deteriorated partners with reduced sperm quality.

Aroma chemicals

[edit]Products of carotenoid degradation such as ionones, damascones and damascenones are also important fragrance chemicals that are used extensively in the perfumes and fragrance industry. Both β-damascenone and β-ionone although low in concentration in rose distillates are the key odor-contributing compounds in flowers. In fact, the sweet floral smells present in black tea, aged tobacco, grape, and many fruits are due to the aromatic compounds resulting from carotenoid breakdown.

Disease

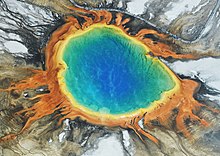

[edit]Some carotenoids are produced by bacteria to protect themselves from oxidative immune attack. The aureus (golden) pigment that gives some strains of Staphylococcus aureus their name is a carotenoid called staphyloxanthin. This carotenoid is a virulence factor with an antioxidant action that helps the microbe evade death by reactive oxygen species used by the host immune system.[39]

Biosynthesis

[edit]

The basic building blocks of carotenoids are isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP).[40] These two isoprene isomers are used to create various compounds depending on the biological pathway used to synthesize the isomers.[41] Plants are known to use two different pathways for IPP production: the cytosolic mevalonic acid pathway (MVA) and the plastidic methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP).[40] In animals, the production of cholesterol starts by creating IPP and DMAPP using the MVA.[41] For carotenoid production plants use MEP to generate IPP and DMAPP.[40] The MEP pathway results in a 5:1 mixture of IPP:DMAPP.[41] IPP and DMAPP undergo several reactions, resulting in the major carotenoid precursor, geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP). GGPP can be converted into carotenes or xanthophylls by undergoing a number of different steps within the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway.[40]

MEP pathway

[edit]Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and pyruvate, intermediates of photosynthesis, are converted to deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) catalyzed by DXP synthase (DXS). DXP reductoisomerase catalyzes the reduction by NADPH and subsequent rearrangement.[40][41] The resulting MEP is converted to 4-(cytidine 5’-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol (CDP-ME) in the presence of CTP using the enzyme MEP cytidylyltransferase. CDP-ME is then converted, in the presence of ATP, to 2-phospho-4-(cytidine 5’-diphospho)-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol (CDP-ME2P). The conversion to CDP-ME2P is catalyzed by CDP-ME kinase. Next, CDP-ME2P is converted to 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate (MECDP). This reaction occurs when MECDP synthase catalyzes the reaction and CMP is eliminated from the CDP-ME2P molecule. MECDP is then converted to (e)-4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl diphosphate (HMBDP) via HMBDP synthase in the presence of flavodoxin and NADPH. HMBDP is reduced to IPP in the presence of ferredoxin and NADPH by the enzyme HMBDP reductase. The last two steps involving HMBPD synthase and reductase can only occur in completely anaerobic environments. IPP is then able to isomerize to DMAPP via IPP isomerase.[41]

Carotenoid biosynthetic pathway

[edit]

Two GGPP molecules condense via phytoene synthase (PSY), forming the 15-cis isomer of phytoene. PSY belongs to the squalene/phytoene synthase family and is homologous to squalene synthase that takes part in steroid biosynthesis. The subsequent conversion of phytoene into all-trans-lycopene depends on the organism. Bacteria and fungi employ a single enzyme, the bacterial phytoene desaturase (CRTI) for the catalysis. Plants and cyanobacteria however utilize four enzymes for this process.[42] The first of these enzymes is a plant-type phytoene desaturase which introduces two additional double bonds into 15-cis-phytoene by dehydrogenation and isomerizes two of its existing double bonds from trans to cis producing 9,15,9’-tri-cis-ζ-carotene. The central double bond of this tri-cis-ζ-carotene is isomerized by the zeta-carotene isomerase Z-ISO and the resulting 9,9'-di-cis-ζ-carotene is dehydrogenated again via a ζ-carotene desaturase (ZDS). This again introduces two double bonds, resulting in 7,9,7’,9’-tetra-cis-lycopene. CRTISO, a carotenoid isomerase, is needed to convert the cis-lycopene into an all-trans lycopene in the presence of reduced FAD.

This all-trans lycopene is cyclized; cyclization gives rise to carotenoid diversity, which can be distinguished based on the end groups. There can be either a beta ring or an epsilon ring, each generated by a different enzyme (lycopene beta-cyclase [beta-LCY] or lycopene epsilon-cyclase [epsilon-LCY]). α-Carotene is produced when the all-trans lycopene first undergoes reaction with epsilon-LCY then a second reaction with beta-LCY; whereas β-carotene is produced by two reactions with beta-LCY. α- and β-Carotene are the most common carotenoids in the plant photosystems but they can still be further converted into xanthophylls by using beta-hydrolase and epsilon-hydrolase, leading to a variety of xanthophylls.[40]

Regulation

[edit]It is believed that both DXS and DXR are rate-determining enzymes, allowing them to regulate carotenoid levels.[40] This was discovered in an experiment where DXS and DXR were genetically overexpressed, leading to increased carotenoid expression in the resulting seedlings.[40] Also, J-protein (J20) and heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) chaperones are thought to be involved in post-transcriptional regulation of DXS activity, such that mutants with defective J20 activity exhibit reduced DXS enzyme activity while accumulating inactive DXS protein.[43] Regulation may also be caused by external toxins that affect enzymes and proteins required for synthesis. Ketoclomazone is derived from herbicides applied to soil and binds to DXP synthase.[41] This inhibits DXP synthase, preventing synthesis of DXP and halting the MEP pathway.[41] The use of this toxin leads to lower levels of carotenoids in plants grown in the contaminated soil.[41] Fosmidomycin, an antibiotic, is a competitive inhibitor of DXP reductoisomerase due to its similar structure to the enzyme.[41] Application of said antibiotic prevents reduction of DXP, again halting the MEP pathway. [41]

Naturally occurring carotenoids

[edit]- Hydrocarbons

- Lycopersene 7,8,11,12,15,7',8',11',12',15'-Decahydro-γ,γ-carotene

- Phytofluene

- Lycopene

- Hexahydrolycopene 15-cis-7,8,11,12,7',8'-Hexahydro-γ,γ-carotene

- Torulene 3',4'-Didehydro-β,γ-carotene

- α-Zeacarotene 7',8'-Dihydro-ε,γ-carotene

- α-Carotene

- β-Carotene

- γ-Carotene

- δ-Carotene

- ε-Carotene

- ζ-Carotene

- Alcohols

- Alloxanthin

- Bacterioruberin 2,2'-Bis(3-hydroxy-3-methylbutyl)-3,4,3',4'-tetradehydro-1,2,1',2'-tetrahydro-γ,γ-carotene-1,1'-diol

- Cynthiaxanthin

- Pectenoxanthin

- Cryptomonaxanthin (3R,3'R)-7,8,7',8'-Tetradehydro-β,β-carotene-3,3'-diol

- Crustaxanthin β,-Carotene-3,4,3',4'-tetrol

- Gazaniaxanthin (3R)-5'-cis-β,γ-Caroten-3-ol

- OH-Chlorobactene 1',2'-Dihydro-f,γ-caroten-1'-ol

- Loroxanthin β,ε-Carotene-3,19,3'-triol

- Lutein (3R,3′R,6′R)-β,ε-carotene-3,3′-diol

- Lycoxanthin γ,γ-Caroten-16-ol

- Rhodopin 1,2-Dihydro-γ,γ-caroten-l-ol

- Rhodopinol a.k.a. Warmingol 13-cis-1,2-Dihydro-γ,γ-carotene-1,20-diol

- Saproxanthin 3',4'-Didehydro-1',2'-dihydro-β,γ-carotene-3,1'-diol

- Zeaxanthin

- Glycosides

- Oscillaxanthin 2,2'-Bis(β-L-rhamnopyranosyloxy)-3,4,3',4'-tetradehydro-1,2,1',2'-tetrahydro-γ,γ-carotene-1,1'-diol

- Phleixanthophyll 1'-(β-D-Glucopyranosyloxy)-3',4'-didehydro-1',2'-dihydro-β,γ-caroten-2'-ol

- Ethers

- Rhodovibrin 1'-Methoxy-3',4'-didehydro-1,2,1',2'-tetrahydro-γ,γ-caroten-1-ol

- Spheroidene 1-Methoxy-3,4-didehydro-1,2,7',8'-tetrahydro-γ,γ-carotene

- Epoxides

- Diadinoxanthin 5,6-Epoxy-7',8'-didehydro-5,6-dihydro—carotene-3,3-diol

- Luteoxanthin 5,6: 5',8'-Diepoxy-5,6,5',8'-tetrahydro-β,β-carotene-3,3'-diol

- Mutatoxanthin

- Citroxanthin

- Zeaxanthin furanoxide 5,8-Epoxy-5,8-dihydro-β,β-carotene-3,3'-diol

- Neochrome 5',8'-Epoxy-6,7-didehydro-5,6,5',8'-tetrahydro-β,β-carotene-3,5,3'-triol

- Foliachrome

- Trollichrome

- Vaucheriaxanthin 5',6'-Epoxy-6,7-didehydro-5,6,5',6'-tetrahydro-β,β-carotene-3,5,19,3'-tetrol

- Aldehydes

- Rhodopinal

- Warmingone 13-cis-1-Hydroxy-1,2-dihydro-γ,γ-caroten-20-al

- Torularhodinaldehyde 3',4'-Didehydro-β,γ-caroten-16'-al

- Acids and acid esters

- Torularhodin 3',4'-Didehydro-β,γ-caroten-16'-oic acid

- Torularhodin methyl ester Methyl 3',4'-didehydro-β,γ-caroten-16'-oate

- Ketones

- Astacene

- Astaxanthin

- Canthaxanthin[44] a.k.a. Aphanicin, Chlorellaxanthin β,β-Carotene-4,4'-dione

- Capsanthin (3R,3'S,5'R)-3,3'-Dihydroxy-β,κ-caroten-6'-one

- Capsorubin (3S,5R,3'S,5'R)-3,3'-Dihydroxy-κ,κ-carotene-6,6'-dione

- Cryptocapsin (3'R,5'R)-3'-Hydroxy-β,κ-caroten-6'-one

- 2,2'-Diketospirilloxanthin 1,1'-Dimethoxy-3,4,3',4'-tetradehydro-1,2,1',2'-tetrahydro-γ,γ-carotene-2,2'-dione

- Echinenone β,β-Caroten-4-one

- 3'-Hydroxyechinenone

- Flexixanthin 3,1'-Dihydroxy-3',4'-didehydro-1',2'-dihydro-β,γ-caroten-4-one

- 3-OH-Canthaxanthin a.k.a. Adonirubin a.k.a. Phoenicoxanthin 3-Hydroxy-β,β-carotene-4,4'-dione

- Hydroxyspheriodenone 1'-Hydroxy-1-methoxy-3,4-didehydro-1,2,1',2',7',8'-hexahydro-γ,γ-caroten-2-one

- Okenone 1'-Methoxy-1',2'-dihydro-c,γ-caroten-4'-one

- Pectenolone 3,3'-Dihydroxy-7',8'-didehydro-β,β-caroten-4-one

- Phoeniconone a.k.a. Dehydroadonirubin 3-Hydroxy-2,3-didehydro-β,β-carotene-4,4'-dione

- Phoenicopterone β,ε-caroten-4-one

- Rubixanthone 3-Hydroxy-β,γ-caroten-4'-one

- Siphonaxanthin 3,19,3'-Trihydroxy-7,8-dihydro-β,ε-caroten-8-one

- Esters of alcohols

- Astacein 3,3'-Bispalmitoyloxy-2,3,2',3'-tetradehydro-β,β-carotene-4,4'-dione or 3,3'-dihydroxy-2,3,2',3'-tetradehydro-β,β-carotene-4,4'-dione dipalmitate

- Fucoxanthin 3'-Acetoxy-5,6-epoxy-3,5'-dihydroxy-6',7'-didehydro-5,6,7,8,5',6'-hexahydro-β,β-caroten-8-one

- Isofucoxanthin 3'-Acetoxy-3,5,5'-trihydroxy-6',7'-didehydro-5,8,5',6'-tetrahydro-β,β-caroten-8-one

- Physalien

- Siphonein 3,3'-Dihydroxy-19-lauroyloxy-7,8-dihydro-β,ε-caroten-8-one or 3,19,3'-trihydroxy-7,8-dihydro-β,ε-caroten-8-one 19-laurate

- Apocarotenoids

- β-Apo-2'-carotenal 3',4'-Didehydro-2'-apo-b-caroten-2'-al

- Apo-2-lycopenal

- Apo-6'-lycopenal 6'-Apo-y-caroten-6'-al

- Azafrinaldehyde 5,6-Dihydroxy-5,6-dihydro-10'-apo-β-caroten-10'-al

- Bixin 6'-Methyl hydrogen 9'-cis-6,6'-diapocarotene-6,6'-dioate

- Citranaxanthin 5',6'-Dihydro-5'-apo-β-caroten-6'-one or 5',6'-dihydro-5'-apo-18'-nor-β-caroten-6'-one or 6'-methyl-6'-apo-β-caroten-6'-one

- Crocetin 8,8'-Diapo-8,8'-carotenedioic acid

- Crocetinsemialdehyde 8'-Oxo-8,8'-diapo-8-carotenoic acid

- Crocin Digentiobiosyl 8,8'-diapo-8,8'-carotenedioate

- Hopkinsiaxanthin 3-Hydroxy-7,8-didehydro-7',8'-dihydro-7'-apo-b-carotene-4,8'-dione or 3-hydroxy-8'-methyl-7,8-didehydro-8'-apo-b-carotene-4,8'-dione

- Methyl apo-6'-lycopenoate Methyl 6'-apo-y-caroten-6'-oate

- Paracentrone 3,5-Dihydroxy-6,7-didehydro-5,6,7',8'-tetrahydro-7'-apo-b-caroten-8'-one or 3,5-dihydroxy-8'-methyl-6,7-didehydro-5,6-dihydro-8'-apo-b-caroten-8'-one

- Sintaxanthin 7',8'-Dihydro-7'-apo-b-caroten-8'-one or 8'-methyl-8'-apo-b-caroten-8'-one

- Nor- and seco-carotenoids

- Actinioerythrin 3,3'-Bisacyloxy-2,2'-dinor-b,b-carotene-4,4'-dione

- β-Carotenone 5,6:5',6'-Diseco-b,b-carotene-5,6,5',6'-tetrone

- Peridinin 3'-Acetoxy-5,6-epoxy-3,5'-dihydroxy-6',7'-didehydro-5,6,5',6'-tetrahydro-12',13',20'-trinor-b,b-caroten-19,11-olide

- Pyrrhoxanthininol 5,6-epoxy-3,3'-dihydroxy-7',8'-didehydro-5,6-dihydro-12',13',20'-trinor-b,b-caroten-19,11-olide

- Semi-α-carotenone 5,6-Seco-b,e-carotene-5,6-dione

- Semi-β-carotenone 5,6-seco-b,b-carotene-5,6-dione or 5',6'-seco-b,b-carotene-5',6'-dione

- Triphasiaxanthin 3-Hydroxysemi-b-carotenone 3'-Hydroxy-5,6-seco-b,b-carotene-5,6-dione or 3-hydroxy-5',6'-seco-b,b-carotene-5',6'-dione

- Retro-carotenoids and retro-apo-carotenoids

- Eschscholtzxanthin 4',5'-Didehydro-4,5'-retro-b,b-carotene-3,3'-diol

- Eschscholtzxanthone 3'-Hydroxy-4',5'-didehydro-4,5'-retro-b,b-caroten-3-one

- Rhodoxanthin 4',5'-Didehydro-4,5'-retro-b,b-carotene-3,3'-dione

- Tangeraxanthin 3-Hydroxy-5'-methyl-4,5'-retro-5'-apo-b-caroten-5'-one or 3-hydroxy-4,5'-retro-5'-apo-b-caroten-5'-one

- Higher carotenoids

- Nonaprenoxanthin 2-(4-Hydroxy-3-methyl-2-butenyl)-7',8',11',12'-tetrahydro-e,y-carotene

- Decaprenoxanthin 2,2'-Bis(4-hydroxy-3-methyl-2-butenyl)-e,e-carotene

- C.p. 450 2-[4-Hydroxy-3-(hydroxymethyl)-2-butenyl]-2'-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)-b,b-carotene

- C.p. 473 2'-(4-Hydroxy-3-methyl-2-butenyl)-2-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)-3',4'-didehydro-l',2'-dihydro-β,γ-caroten-1'-ol

- Bacterioruberin 2,2'-Bis(3-hydroxy-3-methylbutyl)-3,4,3',4'-tetradehydro-1,2,1',2'-tetrahydro-γ,γ-carotene-1,1'-diol

See also

[edit]- List of phytochemicals in food

- CRT (genetics), gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis of carotenoids

- E number#E100–E199 (colours)

- Phytochemistry

References

[edit]- ^ Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2005). Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- ^ Yabuzaki, Junko (2017-01-01). "Carotenoids Database: structures, chemical fingerprints and distribution among organisms". Database. 2017 (1). doi:10.1093/database/bax004. PMC 5574413. PMID 28365725.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Carotenoids". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. 1 August 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ Armstrong GA, Hearst JE (1996). "Carotenoids 2: Genetics and molecular biology of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis". FASEB J. 10 (2): 228–37. doi:10.1096/fasebj.10.2.8641556. PMID 8641556. S2CID 22385652.

- ^ a b Bernstein, P. S.; Li, B; Vachali, P. P.; Gorusupudi, A; Shyam, R; Henriksen, B. S.; Nolan, J. M. (2015). "Lutein, Zeaxanthin, and meso-Zeaxanthin: The Basic and Clinical Science Underlying Carotenoid-based Nutritional Interventions against Ocular Disease". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 50: 34–66. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.10.003. PMC 4698241. PMID 26541886.

- ^ Maresca, Julia A.; Romberger, Steven P.; Bryant, Donald A. (2008-05-28). "Isorenieratene Biosynthesis in Green Sulfur Bacteria Requires the Cooperative Actions of Two Carotenoid Cyclases". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (19): 6384–6391. doi:10.1128/JB.00758-08. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 2565998. PMID 18676669.

- ^ a b c Cogdell, R. J. (1978-11-30). "Carotenoids in photosynthesis". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 284 (1002): 569–579. Bibcode:1978RSPTB.284..569C. doi:10.1098/rstb.1978.0090. ISSN 0080-4622.

- ^ Finkelstein, Ruth (2013-11-01). "Abscisic Acid Synthesis and Response". The Arabidopsis Book. 11: e0166. doi:10.1199/tab.0166. ISSN 1543-8120. PMC 3833200. PMID 24273463.

- ^ a b c Vershinin, Alexander (1999-01-01). "Biological functions of carotenoids - diversity and evolution". BioFactors. 10 (2–3): 99–104. doi:10.1002/biof.5520100203. ISSN 1872-8081. PMID 10609869. S2CID 24408277.

- ^ Polívka, Tomáš; Sundström, Villy (2004). "Ultrafast Dynamics of Carotenoid Excited States−From Solution to Natural and Artificial Systems". Chemical Reviews. 104 (4): 2021–2072. doi:10.1021/cr020674n. PMID 15080720.

- ^ Ramel, Fanny; Birtic, Simona; Cuiné, Stéphan; Triantaphylidès, Christian; Ravanat, Jean-Luc; Havaux, Michel (2012). "Chemical Quenching of Singlet Oxygen by Carotenoids in Plants". Plant Physiology. 158 (3): 1267–1278. doi:10.1104/pp.111.182394. PMC 3291260. PMID 22234998.

- ^ John Thomas Landrum (2010). Carotenoids: physical, chemical, and biological functions and properties. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-5230-5. OCLC 148650411.

- ^ Gruszecki, Wieslaw I. (2004), Frank, Harry A.; Young, Andrew J.; Britton, George; Cogdell, Richard J. (eds.), "Carotenoids in Membranes", The Photochemistry of Carotenoids, Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration, vol. 8, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 363–379, doi:10.1007/0-306-48209-6_20, ISBN 978-0-7923-5942-5, retrieved 2021-03-28

- ^ Timlin, Jerilyn A.; Collins, Aaron M.; Beechem, Thomas A.; Shumskaya, Maria; Wurtzel, Eleanore T. (2017-06-14), "Localizing and Quantifying Carotenoids in Intact Cells and Tissues", Carotenoids, InTech, doi:10.5772/68101, ISBN 978-953-51-3211-0, S2CID 54807067

- ^ Petyaev, Ivan M.; Zigangirova, Naylia A.; Pristensky, Dmitry; et al. (2018). "Non-Invasive Immunofluorescence Assessment of Lycopene Supplementation Status in Skin Smears". Monoclonal Antibodies in Immunodiagnosis and Immunotherapy. 37 (3): 139–146. doi:10.1089/mab.2018.0012. ISSN 2167-9436. PMID 29901405. S2CID 49190846.

- ^ "Foods Highest in Retinol Activity Equivalent". nutritiondata.self.com. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

- ^ Tran, X. T.; Parks, S. E.; Roach, P. D.; Golding, J. B.; Nguyen, M. H. (2015). "Effects of maturity on physicochemical properties of Gac fruit (Momordica cochinchinensis Spreng.)". Food Science & Nutrition. 4 (2): 305–314. doi:10.1002/fsn3.291. PMC 4779482. PMID 27004120.

- ^ Yim, K. J.; Kwon, J; Cha, I. T.; Oh, K. S.; Song, H. S.; Lee, H. W.; Rhee, J. K.; Song, E. J.; Rho, J. R.; Seo, M. L.; Choi, J. S.; Choi, H. J.; Lee, S. J.; Nam, Y. D.; Roh, S. W. (2015). "Occurrence of viable, red-pigmented haloarchaea in the plumage of captive flamingoes". Scientific Reports. 5: 16425. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516425Y. doi:10.1038/srep16425. PMC 4639753. PMID 26553382.

- ^ Leoncini; Sources, Natural; Head; Cancer, Neck; et al. (July 2015). "A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Epidemiological Studies". Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 24 (7): 1003–11. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0053. PMID 25873578. S2CID 21131127.

- ^ Soares Nda, C; et al. (October 2015). "Anticancer properties of carotenoids in prostate cancer. A review" (PDF). Histol Histopathol. 30 (10): 1143–54. doi:10.14670/HH-11-635. PMID 26058846.

- ^ Takeda, A; et al. (2014). "Vitamin A and carotenoids and the risk of Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Neuroepidemiology. 42 (1): 25–38. doi:10.1159/000355849. PMID 24356061. S2CID 12396064.

- ^ Sacchi, Roberto (4 June 2013). "Colour variation in the polymorphic common wall lizard (Podarcis muralis): An analysis using the RGB colour system". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 252 (4): 431–439. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2013.03.001.

- ^ Whitehead RD, Ozakinci G, Perrett DI (2012). "Attractive skin coloration: harnessing sexual selection to improve diet and health". Evol Psychol. 10 (5): 842–54. doi:10.1177/147470491201000507. PMC 10429994. PMID 23253790. S2CID 8655801.

- ^ a b Mashurabad, Purna Chandra; Palika, Ravindranadh; Jyrwa, Yvette Wilda; Bhaskarachary, K.; Pullakhandam, Raghu (3 January 2017). "Dietary fat composition, food matrix and relative polarity modulate the micellarization and intestinal uptake of carotenoids from vegetables and fruits". Journal of Food Science and Technology. 54 (2): 333–341. doi:10.1007/s13197-016-2466-7. ISSN 0022-1155. PMC 5306026. PMID 28242932.

- ^ Rodrigo, María Jesús; Cilla, Antonio; Barberá, Reyes; Zacarías, Lorenzo (2015). "Carotenoid bioaccessibility in pulp and fresh juice from carotenoid-rich sweet oranges and mandarins". Food & Function. 6 (6): 1950–1959. doi:10.1039/c5fo00258c. PMID 25996796.

- ^ Archetti, Marco; Döring, Thomas F.; Hagen, Snorre B.; Hughes, Nicole M.; Leather, Simon R.; Lee, David W.; Lev-Yadun, Simcha; Manetas, Yiannis; Ougham, Helen J. (2011). "Unravelling the evolution of autumn colours: an interdisciplinary approach". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 24 (3): 166–73. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.006. PMID 19178979.

- ^ Davies, Kevin M., ed. (2004). Plant pigments and their manipulation. Annual Plant Reviews. Vol. 14. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4051-1737-1.

- ^ Delhey, Kaspar; Peters, Anne (2016-11-16). "The effect of colour-producing mechanisms on plumage sexual dichromatism in passerines and parrots". Functional Ecology. 31 (4): 903–914. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12796. ISSN 0269-8463.

- ^ Thomas, Daniel B.; McGraw, Kevin J.; Butler, Michael W.; Carrano, Matthew T.; Madden, Odile; James, Helen F. (2014-08-07). "Ancient origins and multiple appearances of carotenoid-pigmented feathers in birds". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1788): 20140806. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0806. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 4083795. PMID 24966316.

- ^ a b Cooney, Christopher R.; Varley, Zoë K.; Nouri, Lara O.; Moody, Christopher J. A.; Jardine, Michael D.; Thomas, Gavin H. (2019-04-16). "Sexual selection predicts the rate and direction of colour divergence in a large avian radiation". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1773. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1773C. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09859-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6467902. PMID 30992444.

- ^ Hill, Geoffrey E. (September 1990). "Female house finches prefer colourful males: sexual selection for a condition-dependent trait". Animal Behaviour. 40 (3): 563–572. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(05)80537-8. ISSN 0003-3472. S2CID 53176725.

- ^ Weaver, Ryan J.; Santos, Eduardo S. A.; Tucker, Anna M.; Wilson, Alan E.; Hill, Geoffrey E. (2018-01-08). "Carotenoid metabolism strengthens the link between feather coloration and individual quality". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 73. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9...73W. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02649-z. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5758789. PMID 29311592.

- ^ Simons, Mirre J. P.; Cohen, Alan A.; Verhulst, Simon (2012-08-14). "What Does Carotenoid-Dependent Coloration Tell? Plasma Carotenoid Level Signals Immunocompetence and Oxidative Stress State in Birds–A Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. 7 (8): e43088. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...743088S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043088. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3419220. PMID 22905205.

- ^ Koch, Rebecca E.; Hill, Geoffrey E. (2018-05-14). "Do carotenoid-based ornaments entail resource trade-offs? An evaluation of theory and data". Functional Ecology. 32 (8): 1908–1920. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.13122. ISSN 0269-8463.

- ^ Hill, Geoffrey E.; Johnson, James D. (November 2012). "The Vitamin A–Redox Hypothesis: A Biochemical Basis for Honest Signaling via Carotenoid Pigmentation". The American Naturalist. 180 (5): E127–E150. doi:10.1086/667861. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 23070328. S2CID 2013258.

- ^ Powers, Matthew J; Hill, Geoffrey E (2021-05-03). "A Review and Assessment of the Shared-Pathway Hypothesis for the Maintenance of Signal Honesty in Red Ketocarotenoid-Based Coloration". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 61 (5): 1811–1826. doi:10.1093/icb/icab056. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 33940618.

- ^ Helfenstein, Fabrice; Losdat, Sylvain; Møller, Anders Pape; Blount, Jonathan D.; Richner, Heinz (February 2010). "Sperm of colourful males are better protected against oxidative stress". Ecology Letters. 13 (2): 213–222. Bibcode:2010EcolL..13..213H. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01419.x. ISSN 1461-0248. PMID 20059524.

- ^ a b Kim, Sin-Yeon; Velando, Alberto (January 2020). "Attractive male sticklebacks carry more oxidative DNA damage in the soma and germline". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 33 (1): 121–126. doi:10.1111/jeb.13552. ISSN 1420-9101. PMID 31610052. S2CID 204702365.

- ^ Liu GY, Essex A, Buchanan JT, et al. (2005). "Staphylococcus aureus golden pigment impairs neutrophil killing and promotes virulence through its antioxidant activity". J. Exp. Med. 202 (2): 209–15. doi:10.1084/jem.20050846. PMC 2213009. PMID 16009720.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nisar, Nazia; Li, Li; Lu, Shan; Khin, Nay Chi; Pogson, Barry J. (2015-01-05). "Carotenoid Metabolism in Plants". Molecular Plant. Plant Metabolism and Synthetic Biology. 8 (1): 68–82. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2014.12.007. PMID 25578273. S2CID 26818009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j KUZUYAMA, Tomohisa; SETO, Haruo (2012-03-09). "Two distinct pathways for essential metabolic precursors for isoprenoid biosynthesis". Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Series B, Physical and Biological Sciences. 88 (3): 41–52. Bibcode:2012PJAB...88...41K. doi:10.2183/pjab.88.41. ISSN 0386-2208. PMC 3365244. PMID 22450534.

- ^ Moise, Alexander R.; Al-Babili, Salim; Wurtzel, Eleanore T. (31 October 2013). "Mechanistic aspects of carotenoid biosynthesis". Chemical Reviews. 114 (1): 164–93. doi:10.1021/cr400106y. PMC 3898671. PMID 24175570.

- ^ Nisar, Nazia; Li, Li; Lu, Shan; ChiKhin, Nay; Pogson, Barry J. (5 January 2015). "Carotenoid Metabolism in Plants". Molecular Plant. 8 (1): 68–82. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2014.12.007. PMID 25578273. S2CID 26818009.

- ^ Choi, Seyoung; Koo, Sangho (2005). "Efficient Syntheses of the Keto-carotenoids Canthaxanthin, Astaxanthin, and Astacene". J. Org. Chem. 70 (8): 3328–3331. doi:10.1021/jo050101l. PMID 15823009.

External links

[edit]- Carotenoids at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Types of plant pigments | |

|---|---|

| Betalains | |

| Chlorophyll | |

| Curcuminoids | |

| Flavonoids | |

| Carotenoids | |

| Other | |

| Carotenes (C40) | |

|---|---|

| Xanthophylls (C40) | |

| Apocarotenoids (C<40) | |

| Vitamin A retinoids (C20) | |

| Retinoid drugs |

|

| Basic forms: | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemiterpenoids (1) |

| ||||||||||||

| Monoterpenes (C10H16)(2) |

| ||||||||||||

| Monoterpenoids (2,modified) |

| ||||||||||||

| Sesquiterpenoids (3) |

| ||||||||||||

| Diterpenoids (4) |

| ||||||||||||

| Sesterterpenoids (5) |

| ||||||||||||

| Triterpenoids (6) |

| ||||||||||||

| Sesquarterpenes/oids (7) |

| ||||||||||||

| Tetraterpenoids (Carotenoids) (8) |

| ||||||||||||

| Polyterpenoids (many) |

| ||||||||||||

| Norisoprenoids (modified) |

| ||||||||||||

| Synthesis |

| ||||||||||||

| Activated isoprene forms |

| ||||||||||||

| Mevalonate pathway |

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-mevalonate pathway | |||||||||||

| To Cholesterol |

| ||||||||||

| From Cholesterol to Steroid hormones |

| ||||||||||

| Nonhuman |

| ||||||||||