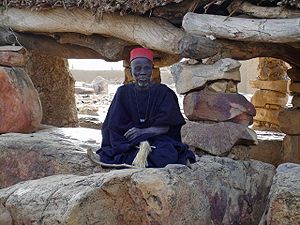

Dogon men in their ceremonial attire | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,591,787 (2012–2013) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,751,965 (8.7%)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Dogon languages, Bangime, French | |

| Religion | |

| African traditional religion, Islam, Christianity | |

The Dogon are an ethnic group indigenous to the central plateau region of Mali, in West Africa, south of the Niger bend, near the city of Bandiagara, and in Burkina Faso. The population numbers between 400,000 and 800,000.[2] They speak the Dogon languages, which are considered to constitute an independent branch of the Niger–Congo language family, meaning that they are not closely related to any other languages.[3]

The Dogon are best known for their religious traditions, their mask dances, wooden sculpture, and their architecture. Since the twentieth century, there have been significant changes in the social organisation, material culture and beliefs of the Dogon, in part because Dogon country is one of Mali's major tourist attractions.[4]

|

See also: Toloy and Dogon country |

The principal Dogon area is bisected by the Bandiagara Escarpment, a sandstone cliff of up to 500 metres (1,600 ft) high, stretching about 150 km (90 miles). To the southeast of the cliff, the sandy Séno-Gondo Plains are found, and northwest of the cliff are the Bandiagara Highlands. Historically, Dogon villages were established in the Bandiagara area a thousand years ago because the people collectively refused to convert to Islam and retreated from areas controlled by Muslims.[5]

Dogon insecurity in the face of these historical pressures caused them to locate their villages in defensible positions along the walls of the escarpment. The other factor influencing their choice of settlement location was access to water. The Niger River is nearby and in the sandstone rock, a rivulet runs at the foot of the cliff at the lowest point of the area during the wet season.

Among the Dogon, several oral traditions have been recorded as to their origin. One relates to their coming from Mande, located to the southwest of the Bandiagara escarpment near Bamako. According to this oral tradition, the first Dogon settlement was established in the extreme southwest of the escarpment at Kani-Na.[6][7] Archaeological and ethnoarchaeological studies in the Dogon region have been especially revealing about the settlement and environmental history, and about social practices and technologies in this area over several thousands of years.[8][9][10]

Over time, the Dogon moved north along the escarpment, arriving in the Sanga region in the 15th century.[11] Other oral histories place the origin of the Dogon to the west beyond the river Niger, or tell of the Dogon coming from the east. It is likely that the Dogon of today are descendants of several groups of diverse origin who migrated to escape Islamization.[12]

It is often difficult to distinguish between pre-Muslim practices and later practices. But Islamic law classified the Dogon and many other ethnicities of the region (Mossi, Gurma, Bobo, Busa and the Yoruba) as being within the non-canon dar al-harb and consequently fair game for slave raids organized by merchants.[13] As the growth of cities increased, the demand for slaves across the region of West Africa also increased. The historical pattern included the murder of indigenous males by raiders and enslavement of women and children.[14]

For almost 1000 years,[15] the Dogon people, an ancient ethnic group of Mali[16] had faced religious and ethnic persecution—through jihads by dominant Muslim communities.[15] These jihadic expeditions formed themselves to force the Dogon to abandon their traditional religious beliefs for Islam. Such jihads caused the Dogon to abandon their original villages and moved up to the cliffs of Bandiagara for better defense and to escape persecution—often building their dwellings in little nooks and crannies.[15][17]

|

Main article: African art § Dogon |

Dogon art consists primarily of sculptures. Dogon art revolves around religious values, ideals, and freedoms (Laude, 19). Dogon sculptures are not made to be seen publicly, and are commonly hidden from the public eye within the houses of families, sanctuaries, or kept with the Hogon (Laude, 20). The importance of secrecy is due to the symbolic meaning behind the pieces and the process by which they are made.

Themes found throughout Dogon sculpture consist of figures with raised arms, superimposed bearded figures, horsemen, stools with caryatids, women with children, figures covering their faces, women grinding pearl millet, women bearing vessels on their heads, donkeys bearing cups, musicians, dogs, quadruped-shaped troughs or benches, figures bending from the waist, mirror-images, aproned figures, and standing figures (Laude, 46–52).

Signs of other contacts and origins are evident in Dogon art. The Dogon people were not the first inhabitants of the cliffs of Bandiagara. Influence from Tellem art is evident in Dogon art because of its rectilinear designs (Laude, 24).

Today, at least 35% of the Dogon practice Islam. Another 10% practices Christianity. Those who have accepted one of these two monotheistic religions have abandoned their worship of fetishes (idols) which had been prevalent amongst them.

Dogon society is organized by a patrilineal kinship system. Each Dogon village, or enlarged family, is headed by one male elder. This chief head is the oldest living son of the ancestor of the local branch of the family.

| Part of a series on |

| Traditional African religions |

|---|

|

The blind Dogon elder Ogotemmeli taught the main symbols of the Dogon religion to French anthropologist Marcel Griaule in October 1946.[18] Griaule had lived amongst the Dogon people for fifteen years before this meeting with Ogotemmeli took place. Ogotemmeli taught Griaule the religious stories in the same way that Ogotemmeli had learned them from his father and grandfather; oral instruction which he had learned over the course of more than twenty years.[19] What makes the record so important from a historical perspective is that the Dogon people were still living in their oral culture at the time their religion was recorded. They were one of the last people in West Africa to lose their independence and come under French rule.[18]

The Dogon people with whom French anthropologists Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen worked during the 1930s and 1940s had a system of signs which ran into the thousands, including "their own systems of astronomy and calendrical measurements, methods of calculation and extensive anatomical and physiological knowledge, as well as a systematic pharmacopoeia".[20] The religion embraced many aspects of nature which are found in other traditional African religions.

The key spiritual figures in the religion were the Nummo/Nommo twins. According to Ogotemmêli's description of them, the Nummo, whom he also referred to as "Water", had green skin covered in green hair, and were formed like humans from the loins up, but serpent-like below. Their eyes were red, their tongues forked, and their arms flexible and unjointed.[21]

Ogotemmêli classified the Nummo as hermaphrodites. Their images or figures appeared on the female side of the Dogon sanctuary.[22] They were primarily symbolized by the Sun, which was a female symbol in the religion. In the Dogon language, the Sun's name (nay) had the same root as "mother" (na) and "cow" (nā).[23] They were symbolized by the colour red, a female symbol.

The problem of "twin births" versus "single births", or androgyny versus single-sexed beings, was said to contribute to a disorder at the beginning of time. This theme was fundamental to the Dogon religion. "The jackal was alone from birth," said Ogotemmêli, "and because of this he did more things than can be told."[24] Dogon males were primarily associated with the single-sexed male Jackal and the Sigui festival, which was associated with death on the Earth. It was held once every sixty years and allegedly celebrated the white dwarf star, Sirius B.[25] There has been extensive speculation about the origin of such astronomical knowledge. The colour white was a symbol of males. The ritual language, "Sigi so" or "language of the Sigui", which was taught to male dignitaries of the Society of the Masks ("awa"), was considered a poor language. It contained only about a quarter of the full vocabulary of "Dogo so", the Dogon language. The "Sigi so" was used to tell the story of creation of the universe, of human life, and the advent of death on the Earth, during both funeral ceremonies and the rites of the "end of mourning" ("dama").[26]

Because of the birth of the single-sexed male Jackal, who was born without a soul, all humans eventually had to be turned into single-sexed beings. This was to prevent a being like the Jackal from ever being born on Earth again. "The Nummo foresaw that the original rule of twin births was bound to disappear, and that errors might result comparable to those of the jackal, whose birth was single. Because of his solitary state, the first son of God acted as he did."[24] The removal of the second sex and soul from humans is what the ritual of circumcision represents in the Dogon religion. "The dual soul is a danger; a man should be male, and a woman female. Circumcision and excision are once again the remedy."[27]

The Dogon religion was centered on this loss of twinness or androgyny. Griaule describes it in this passage:

Most of the conversations with Ogotemmêli had indeed turned largely on twins and on the need for duality and the doubling of individual lives. The Eight original Ancestors were really eight pairs ... But after this generation, human beings were usually born single. Dogon religion and Dogon philosophy both expressed a haunting sense of the original loss of twin-ness. The heavenly Powers themselves were dual, and in their Earthly manifestations they constantly intervened in pairs ...[28]

The birth of human twins was celebrated in the Dogon culture in Griaule's day because it recalled the "fabulous past, when all beings came into existence in twos, symbols of the balance between humans and the divine". According to Griaule, the celebration of twin-births was a cult that extended all over Africa.[28] Today, a significant minority of the Dogon practice Islam. Another minority practices Christianity.

Those who remain in their ethnic religion generally believe in the significance of the stars and the creator god, Amma, who created Earth and molded it into the shape of a woman,[29] imbuing it with a divine feminine principle.

The vast majority of marriages are monogamous, but nonsororal polygynous marriages are allowed in the Dogon culture. However, even in polygynous marriages, it is rare for a man to have more than two wives. In a polygynous marriage, the wives reside in separate houses within the husband's compound. The first wife, or ya biru, holds a higher position in the family relative to any wives from later marriages. Formally, wives join their husband's household only after the birth of their first child.[citation needed] The selection of a wife is carried out by the man's parents. Marriages are endogamous in that the people are limited to marry only persons within their clan and within their caste.[30]

Women may leave their husbands early in their marriage, before the birth of their first child.[citation needed] After a couple has had children together, divorce is a rare and serious matter, and it requires the participation of the whole village.[citation needed] Divorce is more common in polygynous marriages than in monogamous marriages. In the event of a divorce, the woman takes only the youngest child with her, and the rest remain as a part of the husband's household. An enlarged family can count up to a hundred persons and is called guinna.

The Dogon are strongly oriented toward harmony, which is reflected in many of their rituals. For instance, in one of their most important rituals, the women praise the men, the men thank the women, the young express appreciation for the old, and the old recognize the contributions of the young. Another example is the custom of elaborate greetings whenever one Dogon meets another. This custom is repeated over and over, throughout a Dogon village, all day.

During a greeting ritual, the person who has entered the contact answers a series of questions about his or her whole family, from the person who was already there. The answer is sewa, which means that everything is fine. Then the Dogon who has entered the contact repeats the ritual, asking the resident how his or her whole family is. Because the word sewa is so commonly repeated throughout a Dogon village, neighboring peoples have dubbed the Dogon the sewa people.

|

Main article: Hogon |

The Hogon is the spiritual and political leader of the village. He is elected from among the oldest men of the dominant lineage of the village.

After his election, he has to follow a six-month initiation period, during which he is not allowed to shave or wash. He wears white clothes and nobody is allowed to touch him. A virgin who has not yet had her period takes care of him, cleans his house, and prepares his meals. She returns to her home at night.

After initiation, the Hogon wears a red fez. He has an armband with a sacred pearl that symbolises his function. The virgin is replaced by one of his wives, and she also returns to her home at night. The Hogon has to live alone in his house. The Dogon believe the sacred snake Lébé comes during the night to clean him and to transfer wisdom.

The Dogon are primarily agriculturalists and cultivate millet, sorghum and rice, as well as onions, tobacco, peanuts, and some other vegetables. Griaule encouraged the construction of a dam near Sangha and persuaded the Dogon to cultivate onions. The economy of the Sangha region has doubled since then, and its onions are sold as far as the market of Bamako and those of the Ivory Coast. Grain is stored in granaries.[citation needed]

In addition to agriculture, the women gather wild fruits, tubers, nuts, and honey in the bush outside of village borders. Some young men will hunt for small game, but wild animals are relatively scarce near villages. While the people keep chickens or herds of sheep and goats in Dogon villages, animal husbandry holds little economic value. Individuals with high status may own a small number of cattle.[31]

Since the late 20th century, the Dogon have developed peaceful trading relationships with other societies and have thereby increased variety in their diets. Every four days, Dogon people participate in markets with neighboring tribes, such as the Fulani and the Dyula. The Dogon primarily sell agricultural commodities: onions, grain, cotton, and tobacco. They purchase sugar, salt, European merchandise, and many animal products, such as milk, butter, and dried fish.[citation needed]

There are two endogamous castes in Dogon society: the smiths and the leather-workers. Members of these castes are physically separate from the rest of the village and live either at the village edge or outside of it entirely. While the castes are correlated to profession, membership is determined by birth. The smiths have important ritual powers and are characteristically poor. The leather-workers engage in significant trade with other ethnic groups and accumulate wealth. Unlike norms for the rest of society, parallel-cousin marriage is allowed within castes. Caste boys do not get circumcised.[32]

In Dogon thought, males and females are born with both sexual components. The clitoris is considered male, while the foreskin is considered female.[24] (Originally, for the Dogon, man was endowed with a dual soul. Circumcision is believed to eliminate the superfluous one.[33]) Rites of circumcision enable each sex to assume its proper physical identity.

Boys are circumcised in age groups of three years, counting for example all boys between 9 and 12 years old. This marks the end of their youth, and they are initiated. The blacksmith performs the circumcision. Afterwards, the boys stay for a few days in a hut separated from the rest of the village people, until the wounds have healed. The circumcision is celebrated and the initiated boys go around and receive presents. They make music on a special instrument that is made of a rod of wood and calabashes that makes the sound of a rattle.

The newly circumcised youths, now considered young men, walk around naked for a month after the procedure so that their achievement in age can be admired by the tribe. This practice has been passed down for generations and is always followed, even during winter.

Once a boy is circumcised, he transitions into young adulthood and moves out of his father's house. All of the men in his age-set live together in a duñe until they marry and have children.[34]

The Dogon are among several African ethnic groups that practice female genital mutilation, including a type I circumcision, meaning that the clitoris is removed.[35]

The village of Songho has a circumcision cave ornamented with red and white rock paintings of animals and plants. Nearby is a cave where music instruments are stored.

|

See also: Awa Society |

The Awa is a masked dance society that holds ritual and social importance. It has a strict code of etiquette, obligations, interdicts, and a secret language (sigi sǫ). All initiated Dogon men participate in Awa, with the exception of some caste members. Women are forbidden from joining and prohibited from learning sigi sǫ. The 'Awa' is characterized by the intricate masks worn by members during rituals. There are two major events at which the Awa perform: the 'sigi' ritual and 'dama' funeral rituals.[36]

'Sigi' is a society-wide ritual to honor and recognize the first ancestors. Thought to have originated as a method to unite and keep peace among Dogon villages, the 'sigi' involves all members of the Dogon people. Starting in the northeastern part of Dogon territory, each village takes turns celebrating and hosting elaborate feasts, ceremonies, and festivities. During this time, new masks are carved and dedicated to their ancestors. Each village celebrates for around a year before the 'sigi' moves to the next village. A new 'sigi' is started every 60 years.

Dogon funeral rituals come in two parts. The first occurs immediately after the death of a person, and the second can occur years after the death. Due to the expense, the second traditional funeral rituals, or "damas", are becoming very rare. Damas that are still performed today are not usually performed for their original intent, but instead are performed for tourists interested in the Dogon way of life. The Dogon use this entertainment to earn income by charging tourists money for the masks they want to see and for the ritual itself (Davis, 68).

The traditional dama consists of a masquerade intended to lead the souls of the departed to their final resting places, through a series of ritual dances and rites. Dogon damas include the use of many masks, which they wore by securing them in their teeth, and statuettes. Each Dogon village may differ in the designs of the masks used in the dama ritual. Similarly each village may have their own way of performing the dama rituals. The dama consists of an event, known as the Halic, that is held immediately after the death of a person and lasts for one day (Davis, 68).

According to Shawn R. Davis, this particular ritual incorporates the elements of the yingim and the danyim. During the yincomoli ceremony, a gourd is smashed over the deceased's wooden bowl, hoe, and bundukamba (burial blanket). This announces the entrance of persons wearing the masks used in this ceremony, while the deceased's entrance to his home in the family compound is decorated with ritual elements (Davis, 72–73).

Masks used during the yincomoli ceremony include the Yana Gulay, Satimbe, Sirige, and Kanaga. The Yana Gulay mask's purpose is to impersonate a Fulani woman, and is made from cotton cloth and cowl shells. The Satimbe mask represents the women ancestors, who are said to have discovered the purpose of the masks by guiding the spirits of the deceased into the afterlife (Davis, 74). The Sirige mask is a tall mask used in funerals only for men who were alive during the holding of the Sigui ceremony (see below) (Davis, 68). The Kanaga masqueraders, at one point, dance and sit next to the bundkamba, which represents the deceased.

The yingim and the danyim rituals each last a few days. These events are held annually to honor the elders who have died since the last Dama. The yingim consists of both the sacrifice of cows, or other valuable animals, and mock combat. Large mock battles are performed in order to help chase the spirit, known as the nyama, from the deceased's body and village, and towards the path to the afterlife (Davis, 68).

The danyim is held a couple of months later. During the danyim, masqueraders perform dances every morning and evening for any period up to six days, depending on that village's practice. The masqueraders dance on the rooftops of the deceased's compound, throughout the village, and in the area of fields around the village (Davis, 68). Until the masqueraders have completed their dances, and every ritual has been performed, any misfortune can be blamed on the remaining spirits of the dead (Davis, 68).

Dogon society is composed of several different sects:

Villages are built along escarpments and near a source of water. On average, a village contains around 44 houses organized around the 'ginna', or head man's house. Each village is composed of one main lineage (occasionally, multiple lineages make up a single village) traced through the male line. Houses are built extremely close together, many times sharing walls and floors.

Dogon villages have different buildings:

|

Main article: Dogon languages |

Dogon has been frequently referred to as a single language. There are at least five distinct groups of dialects. The most ancient dialects are dyamsay and tombo, the former being most frequently used for traditional prayers and ritual chants. The Dogon dialects are highly distinct from one another and many varieties are not mutually intelligible, actually amounting to some 12 dialects and 50 sub-dialects. There is also a secret ritual language sigi sǫ (language of Sigi), which is taught to dignitaries (olubarū) of the Society of the Masks – all of whom must be circumcised men – during their enthronement at the Sigui ceremony.[38]

It is generally accepted that the Dogon language belongs to the Niger–Congo language family, though the evidence is weak.[citation needed][why?] They have been linked to the Mande subfamily but also to Gur. In a recent overview of the Niger–Congo family, Dogon is treated as an independent branch.[3]

The Dogon languages show few remnants of a unique noun class system, an example of which is that human nouns take a distinct plural suffix. This leads linguists to conclude that Dogon is likely to have diverged from Niger–Congo very early.[when?] Another indication of this is the subject–object–verb basic word order, which Dogon shares with such early Niger–Congo branches as Ijoid and Mande.

About 1,500 ethnic Dogon in seven villages in southern Mali speak the Bangime language, which is unrelated to the other Dogon languages and presumed by linguists to be an ancient, pre-Dogon language isolate, although a minority of linguists (most notably Roger Blench) hypothesise that it may be related to Proto-Nilo-Saharan.[39]

Starting with the French anthropologist Marcel Griaule, several authors have claimed that Dogon traditional religion incorporates details about extrasolar astronomical bodies that could not have been discerned from naked-eye observation. The idea has entered the New Age and ancient astronaut literature as evidence that extraterrestrial aliens visited Mali in the distant past. Other authors have argued that previous 20th-century European visitors to the Dogon are a far more plausible source of such information and dispute whether Griaule's account accurately describes Dogon myths at all.

From 1931 to 1956, Griaule studied the Dogon in field missions ranging from several days to two months in 1931, 1935, 1937 and 1938[40] and then annually from 1946 until 1956.[41] In late 1946, Griaule spent a consecutive 33 days in conversations with the Dogon wiseman Ogotemmeli, the source of much of Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen's future publications.[42] They reported that the Dogon believe that the brightest star in the night sky, Sirius (Sigi Tolo or "star of the Sigui"[43]), has two companion stars, Pō Tolo (the Digitaria star), and ęmmę ya tolo, (the female Sorghum star), respectively the first and second companions of Sirius A.[44] Sirius, in the Dogon system, formed one of the foci for the orbit of a tiny star, the companionate Digitaria star. When Digitaria is closest to Sirius, that star brightens: when it is farthest from Sirius, it gives off a twinkling effect that suggests to the observer several stars. The orbit cycle takes 50 years.[45] They also claimed that the Dogon appeared to know of the rings of Saturn, and the moons of Jupiter.[46]

Griaule and Dieterlen were puzzled by this 'Sudanese' star system, and prefaced their analysis with the disclaimer, "The problem of knowing how, with no instruments at their disposal, men could know the movements and certain characteristics of virtually invisible stars has not been settled, nor even posed."[47]

More recently, doubts have been raised about the validity of Griaule and Dieterlen's work.[48][49] In a 1991 article in Current Anthropology, anthropologist Wouter van Beek concluded after his research among the Dogon that, "Though they do speak about Sigu Tolo [which is what Griaule claimed the Dogon called Sirius] they disagree completely with each other as to which star is meant; for some it is an invisible star that should rise to announce the sigu [festival], for another it is Venus that, through a different position, appears as Sigu Tolo. All agree, however, that they learned about the star from Griaule."[50]

Griaule's daughter Geneviève Calame-Griaule responded in a later issue, arguing that Van Beek did not go "through the appropriate steps for acquiring knowledge" and suggesting that van Beek's Dogon informants may have thought that he had been "sent by the political and administrative authorities to test the Dogon's Muslim orthodoxy".[51] An independent assessment is given by Andrew Apter of the University of California.[52]

In a 1978 critique, skeptic Ian Ridpath concluded: "There are any number of channels by which the Dogon could have received Western knowledge long before they were visited by Griaule and Dieterlen."[53] In his book Sirius Matters, Noah Brosch postulates that the Dogon may have had contact with astronomers based in Dogon territory during a five-week expedition, led by Henri-Alexandre Deslandres, to study the solar eclipse of 16 April 1893.[54]

Robert Todd Carroll also states that a more likely source of the knowledge of the Sirius star system is from contemporary, terrestrial sources who provided information to interested members of the tribes.[55] James Oberg, however, citing these suspicions notes their completely speculative nature, writing that, "The obviously advanced astronomical knowledge must have come from somewhere, but is it an ancient bequest or a modern graft? Although Temple fails to prove its antiquity, the evidence for the recent acquisition of the information is still entirely circumstantial."[56] Additionally, James Clifford notes that Griaule sought informants best qualified to speak of traditional lore, and deeply mistrusted converts to Christianity, Islam, or people with too much contact with whites.[57]

Oberg points out a number of errors contained in the Dogon beliefs, including the number of moons possessed by Jupiter, that Saturn was the furthest planet from the sun, and the only planet with rings. Interest in other seemingly falsifiable claims, namely concerning a red dwarf star orbiting around Sirius (not hypothesized until the 1950s), led him to entertain a previous challenge by Temple, asserting that "Temple offered another line of reasoning. 'We have in the Dogon information a predictive mechanism which it is our duty to test, regardless of our preconceptions.' One example: 'If a Sirius-C is ever discovered and found to be a red dwarf, I will conclude that the Dogon information has been fully validated.'

This alludes to reports that the Dogon knew of another star in the Sirius system, Ęmmę Ya, or a star "larger than Sirius B but lighter and dim in magnitude". In 1995, gravitational studies indeed showed the possible presence of a brown dwarf star orbiting around Sirius (a Sirius-C) with a six-year orbital period.[58] A more recent study using advanced infrared imaging concluded that the probability of the existence of a triple star system for Sirius is "now low" but could not be ruled out because the region within 5 AU of Sirius A had not been covered.[59]