History

Background

With the decline of the Xianbei confederation, the Murong tribe resettled themselves around the Liaoxi region, where they feuded with the neighbouring Duan and Yuwen tribes. During the Three Kingdoms period, when the Cao Wei commander, Sima Yi, campaigned against Gongsun Yuan in 237, the Murong offered their assistance, and after the campaign, they were allowed to move into northern Liaodong. The Murong became vassals to the Wei and later to Wei's successor, the Western Jin dynasty.

In 285, Murong Hui was installed as the new chieftain of his tribe. Although Hui rebelled against Jin shortly after ascending, he resubmitted in 289 and was given the office of Commander of the Xianbei. Hui moved his tribe inwards, eventually settling at Jicheng (棘城, in modern Jinzhou, Liaoning) and making it their capital, where they adopted an agricultural lifestyle and the Jin governing system. In 307, he declared himself Grand Chanyu of the Xianbei.

During the upheaval of the Five Barbarians, Murong Hui welcomed many refugees fleeing from the disorder into his territory and recruited Han Chinese scholar-officials into his administration.[7] The refugees not only provided the Murong with manpower, but also introduced them to Central Plains culture and advanced agricultural techniques. As the Jin was driven out of the north, Hui effectively held independent control over his territory, but retained his status as a Jin vassal. Between 317 and 318, the Jin court in Jiankang acknowledged his positions and offered him the title of Duke of Changli. Hui initially rejected his ducal title, but in 321, accepted the other title of Duke of Liaodong.

Reign of Murong Huang

Murong Hui died in 333 and was succeeded by his son, Murong Huang. The Murong attempted to establish the Chinese succession rule from father to eldest son of the main wife, but this was in conflict with their traditional practice of lateral succession. Shortly after ascending, Huang's brother, Murong Ren rebelled in eastern Liaodong and split the domain into two. Huang defeated Ren in 336, but the issue of succession continued to persist for the Murong even after they established their states.

In 337, he took the title of Prince of Yan through the support of his officials. Most historians regard this event as the start of the Former Yan dynasty, with the name "Former Yan" being used to distinguish it between the other Yan states that came after it. In 341, Huang pressured the Jin court into formally recognizing his imperial title, but throughout his reign, he never explicitly declared independence and continued to consider himself as a Jin vassal.

Murong Huang's reign saw Former Yan rapidly expanding its influence. In 338, Yan allied with the Later Zhao dynasty to conquer the Duan tribe in Liaoxi. Though the campaign was a success, Zhao then betrayed Yan and laid siege on Jícheng. Despite heavy odds, Yan was able to repel the Zhao forces. In 340, Yan carried out a massive raid on Zhao, reaching all the way to Gaoyang Commandery (高陽郡; around present-day Gaoyang County, Hebei) and capturing 30,000 households before withdrawing.

In 342, Murong Huang moved the capital to Longcheng. Later that year, Former Yan invaded Goguryeo and sacked the capital Hwando, forcing their king Gogugwon into submission. In 344, they attacked the Yuwen tribe and destroyed their power base, while in 346, they invaded Buyeo and captured their king, Hyeon.[8][9] As a result of these campaigns, the Former Yan became the sole military power in northeastern China. Huang also abolished the Eastern Jin era names within his domain in 345, instead claiming that they were now in the 12th year of his reign since he first succeeded his father.

Reign of Murong Jun

After Murong Huang's death in 348, his son Murong Jun took the throne. In 349, the Later Zhao descended into civil war between members of the imperial family. Taking advantage of the confusion, Murong Jun began an invasion of the Central Plains, during which he moved the capital to Jìcheng (薊城; modern day Beijing) in 350. Soon, the Former Yan went head-to-head with the Ran Wei state, which superseded the Later Zhao, and in 352, the Wei emperor, Ran Min was captured by Murong Jun's brother, Murong Ke at the Battle of Liantai. A few months later, Ran Min's Crown Prince, Ran Zhi, surrendered to Former Yan at Ye.

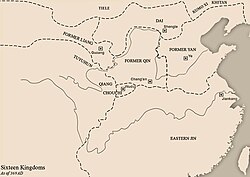

The destruction of Ran Wei established Former Yan as a regional power on the North China Plain, competing with the Di-led Former Qin in the west and the Eastern Jin in the south. In 353, Murong Jun declared himself emperor and formally broke away from Jin. He continued to entrust Murong Ke with defeating the remnants of the Later Zhao, including the Duan Qi state in Shandong. As the situation stabilized on the Central Plains, Jun once again shifted his capital, this time to Ye in 357. Jun also had ambitions to conquer Jin by mobilizing an army of 1.5 million strong, but died of illness before realizing it in 360.

Reign of Murong Wei

Murong Jun's son, Murong Wei was still a child when he ascended the throne and was assigned with multiple regents. Before his death, Jun had offered to pass the throne to Murong Ke, but Ke refused and settled with becoming one of his nephew's regents. Still, Ke held considerable power under Murong Wei, and traditional historians regarded him as one of the most exceptional statesmen and commanders of his period. In 365, he captured the ancient capital, Luoyang from Jin and brought the empire to its peak.

However, although Ke's regency was marked with political stability and military might, corruption was also beginning to take its toll on the empire. One notable issue stemming from corruption was the decline of the state's fiscal revenue due to the nobility's practice of amassing commoners within their private fiefs. These commoners only had to pay taxes to their lords and not to the state, and so the imperial treasury was stretched thin, with many officials having unpaid salaries and the public grain stores being exhausted. Ke's leadership initially mitigated the issue, but the situation quickly deteriorated after his untimely death in 367. Real power was then passed down to his notoriousy corrupt uncle, Murong Ping.

While Murong Ke was entrusted with real power, another brother of Murong Jun, Murong Chui, was viewed with extreme suspicion by the emperor's inner circle throughout Jun and Murong Wei's reigns. In 369, the Eastern Jin commander, Huan Wen, launched an expedition to conquer the Former Yan. As the Yan court was thrown into a panic, Chui volunteered to lead the defense and decisively defeated Huan Wen at the Battle of Fangtou. However, his newfound success made Murong Ping apprehensive of him. After Ping attempted to kill him, Chui defected to the Former Qin.

During the Jin invasion, Yan had agreed to cede the Luoyang region to Qin for reinforcements, but went back on their promise after repelling the attack. Chui’s defection only further prompted Qin to begin their own conquest of Yan. Despite their numerical advantage, the incompetently-led main Yan force was destroyed by Wang Meng's army at the Battle of Luchuan. Qin forces eventually reached Ye and Murong Wei was captured in 370. The destruction of the Former Yan established Former Qin as the main hegemon in the north, beginning their rapid unification of northern China.

Despite the Former Yan's demise, Murong Huang's descendants would go on to establish three more states during the Sixteen Kingdoms period. In the wake of the Former Qin's collapse following the Battle of Fei River in 383, the Yan was restored as the Later Yan (384–407/409), founded by Murong Chui, and the Western Yan (384–394), founded by Murong Wei's brother, Murong Hong. The Southern Yan (398–410) was a Murong state founded by a son of Murong Huang, Murong De.

![Painting depicting a Xianbei Murong archer in a tomb of the Former Yan (337–370).[10]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/23/MurongPainting.jpg/120px-MurongPainting.jpg)