| Hanyu Pinyin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Script type | romanization | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Creator | Pinyin Committee | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Published |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official script |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Standard Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 拼音 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | spelled sounds | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scheme for the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉语拼音方案 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢語拼音方案 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | scheme of spelled Han language sounds | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transliteration of Chinese |

|---|

| Mandarin |

| Wu |

| Yue |

| Min |

| Gan |

| Hakka |

| Xiang |

| Polylectal |

| See also |

Hanyu Pinyin, or simply pinyin, is the most common romanization system for Standard Chinese. In official documents, it is referred to as the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet. Hanyu (汉语; 漢語) literally means 'Han language'—that is, the Chinese language—while pinyin literally means 'spelled sounds'. Pinyin is the official system used in China, Singapore, Taiwan, and by the United Nations. Its use has become common when transliterating Standard Chinese mostly regardless of region, though it is less ubiquitous in Taiwan. It is used to teach Standard Chinese, normally written with Chinese characters, to students already familiar with the Latin alphabet. Pinyin is also used by various input methods on computers and to categorize entries in some Chinese dictionaries.

In pinyin, each Chinese syllable is spelled in terms of an optional initial and a final, each of which is represented by one or more letters. Initials are initial consonants, whereas finals are all possible combinations of medials (semivowels coming before the vowel), a nucleus vowel, and coda (final vowel or consonant). Diacritics are used to indicate the four tones found in Standard Chinese, though these are often omitted in various contexts, such as when spelling Chinese names in non-Chinese texts.

Hanyu Pinyin was developed in the 1950s by a group of Chinese linguists including Wang Li, Lu Zhiwei, Li Jinxi, Luo Changpei and Zhou Youguang, who has been called the "father of pinyin". They based their work in part on earlier romanization systems. The system was originally promulgated at the Fifth Session of the 1st National People's Congress in 1958, and has seen several rounds of revisions since. The International Organization for Standardization propagated Hanyu Pinyin as ISO 7098 in 1982, and the United Nations began using it in 1986. Taiwan adopted Hanyu Pinyin as its official romanization system in 2009, replacing Tongyong Pinyin.

History

[edit]

Background

[edit]Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit missionary in China, wrote the first book that used the Latin alphabet to write Chinese, entitled Xizi Qiji (西字奇蹟; 'Miracle of Western Letters') and published in Beijing in 1605.[1] Twenty years later, fellow Jesuit Nicolas Trigault published 'Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati' (西儒耳目資; Xīrú ěrmù zī)) in Hangzhou.[2] Neither book had any influence among the contemporary Chinese literati, and the romanizations they introduced primarily were useful for Westerners.[3]

During the late Qing, the reformer Song Shu (1862–1910) proposed that China adopt a phonetic writing system. A student of the scholars Yu Yue and Zhang Taiyan, Song had observed the effect of the kana syllabaries and Western learning during his visits to Japan.[which?] While Song did not himself propose a transliteration system for Chinese, his discussion ultimately led to a proliferation of proposed schemes.[3] The Wade–Giles system was produced by Thomas Wade in 1859, and further improved by Herbert Giles, presented in Chinese–English Dictionary (1892). It was popular, and was used in English-language publications outside China until 1979.[4] In 1943, the US military tapped Yale University to develop another romanization system for Mandarin Chinese intended for pilots flying over China—much more than previous systems, the result appears very similar to modern Hanyu Pinyin.

Development

[edit]Hanyu Pinyin was designed by a group of mostly Chinese linguists, including Wang Li, Lu Zhiwei, Li Jinxi, Luo Changpei, as well as Zhou Youguang (1906–2017), an economist by trade, as part of a Chinese government project in the 1950s. Zhou, often called "the father of pinyin",[5][6][7][8] worked as a banker in New York when he decided to return to China to help rebuild the country after the People's Republic was established. Initially, Mao Zedong considered the development of a new writing system for Chinese that only used the Latin alphabet, but during his first official visit to the Soviet Union in 1949, Joseph Stalin convinced him to maintain the existing system.[9] Zhou became an economics professor in Shanghai, and when the Ministry of Education created the Committee for the Reform of the Chinese Written Language in 1955, Premier Zhou Enlai assigned him the task of developing a new romanization system, despite the fact that he was not a linguist by trade.[5]

Hanyu Pinyin incorporated different aspects from existing systems, including Gwoyeu Romatzyh (1928), Latinxua Sin Wenz (1931), and the diacritics from bopomofo (1918).[10] "I'm not the father of pinyin", Zhou said years later; "I'm the son of pinyin. It's [the result of] a long tradition from the later years of the Qing dynasty down to today. But we restudied the problem and revisited it and made it more perfect."[8]

An initial draft was authored in January 1956 by Ye Laishi, Lu Zhiwei and Zhou Youguang. A revised Pinyin scheme was proposed by Wang Li, Lu Zhiwei and Li Jinxi, and became the main focus of discussion among the group of Chinese linguists in June 1956, forming the basis of Pinyin standard later after incorporating a wide range of feedback and further revisions.[11] The first edition of Hanyu Pinyin was approved and officially adopted at the Fifth Session of the 1st National People's Congress on 11 February 1958. It was then introduced to primary schools as a way to teach Standard Chinese pronunciation and used to improve the literacy rate among adults.[12]

During the height of the Cold War the use of pinyin system over Wade–Giles and Yale romanizations outside of China was regarded as a political statement or identification with the mainland Chinese government.[13] Beginning in the early 1980s, Western publications addressing mainland China began using the Hanyu Pinyin romanization system instead of earlier romanization systems; this change followed the Joint Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between the United States and China in 1979.[14][15] In 2001, the Chinese government issued the National Common Language Law, providing a legal basis for applying pinyin.[12] The current specification of the orthography is GB/T 16159–2012.[16]

Syllables

[edit]Chinese phonology is generally described in terms of sound pairs of two initials (声母; 聲母; shēngmǔ) and finals (韵母; 韻母; yùnmǔ). This is distinct from the concept of consonant and vowel sounds as basic units in traditional (and most other phonetic systems used to describe the Chinese language). Every syllable in Standard Chinese can be described as a pair of one initial and one final, except for the special syllable er or when a trailing -r is considered part of a syllable (a phenomenon known as erhua). The latter case, though a common practice in some sub-dialects, is rarely used in official publications.

Even though most initials contain a consonant, finals are not always simple vowels, especially in compound finals (复韵母; 複韻母; fùyùnmǔ), i.e. when a "medial" is placed in front of the final. For example, the medials [i] and [u] are pronounced with such tight openings at the beginning of a final that some native Chinese speakers (especially when singing) pronounce yī (衣; 'clothes') officially pronounced /í/) as /jí/ and wéi (围; 圍; 'to enclose'), officially pronounced /uěi/) as /wěi/ or /wuěi/. Often these medials are treated as separate from the finals rather than as part of them; this convention is followed in the chart of finals below.

Initials

[edit]The conventional lexicographical order derived from bopomofo is:

| b p m f | d t n l | g k h | j q x | zh ch sh r | z c s |

In each cell below, the pinyin letters assigned to each initial are accompanied by their phonetic realizations in brackets, notated according to the International Phonetic Alphabet.

| Pinyin | IPA | Description[17] |

|---|---|---|

| b | [p] | Unaspirated p, like in English spark. |

| p | [pʰ] | Strongly aspirated p, like in English pay. |

| m | [m] | Like the m in English may. |

| f | [f] | Like the f in English fair. |

| d | [t] | Unaspirated t, like in English stop. |

| t | [tʰ] | Strongly aspirated t, like in English take. |

| n | [n] | Like the n in English nay. |

| l | [l]~[ɾ][a] | Like the l in English lay. |

| g | [k] | Unaspirated k, like in English skill. |

| k | [kʰ] | Strongly aspirated k, like in English kiss. |

| h | [x]~[h][a] | Varies between the h in English hat, and the ch in Scottish English loch. |

| j | [tɕ] | Alveolo-palatal, unaspirated. No direct equivalent in English, but similar to the ch in English churchyard. |

| q | [tɕʰ] | Alveolo-palatal, aspirated. No direct equivalent in English, but similar to the ch in English punchy. |

| x | [ɕ] | Alveolo-palatal, unaspirated. No direct equivalent in English, but similar to the sh in English push. |

| zh | [ʈʂ]~[d͡ʒ][a] | Retroflex, unaspirated. Like j in English jack. |

| ch | [ʈʂʰ]~[ʃ][a] | Retroflex, aspirated. Like ch in English church. |

| sh | [ʂ]~[ɹ̠̊˔][a] | Retroflex, unaspirated. Like sh in shirt. |

| r | [ɻ~ʐ]~[ɹ][a] | Retroflex. No direct equivalent in English, but varies between the r in English reduce and the s in English measure. |

| z | [ts] | Unaspirated. Like the zz in English pizza. |

| c | [tsʰ] | Aspirated. Like the ts in English bats. |

| s | [s] | Like the s in English say. |

| w[b] | [w] | Like the w in English water. |

| y[b] | [j], [ɥ] | Either like the y in English yes—or when followed by a u, see below. |

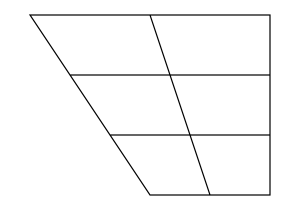

Finals

[edit]In each cell below, the first line indicates the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) transcription, the second indicates pinyin for a standalone (no-initial) form, and the third indicates pinyin for a combination with an initial. Other than finals modified by an -r, which are omitted, the following is an exhaustive table of all possible finals.

The only syllable-final consonants in Standard Chinese are -n, -ng, and -r, the last of which is attached as a grammatical suffix. A Chinese syllable ending with any other consonant either is from a non-Mandarin language (a southern Chinese language such as Cantonese, reflecting final consonants in Old Chinese), or indicates the use of a non-pinyin romanization system, such as one that uses final consonants to indicate tones.

Rime Medial

|

∅ | -e / -o / -ê | -a | -ei | -ai | -ou | -ao | -en | -an | -eng | -ang | er | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∅ | [ɨ]

|

[ɤ]

|

[ɛ]

|

[a]

|

[ei̯]

|

[ai̯]

|

[ou̯]

|

[au̯]

|

[ən]

|

[an]

|

[əŋ]

|

[aŋ]

|

[ɚ]

|

|

[i]

|

[je]

|

[ja]

|

[jou̯]

|

[jau̯]

|

[in]

|

[jɛn]

|

[iŋ]

|

[jaŋ]

|

||||

|

[u]

|

[wo]

|

[wa]

|

[wei̯]

|

[wai̯]

|

[wən]

|

[wan]

|

[wəŋ~ʊŋ]

|

[waŋ]

| ||||

|

[y]

|

[ɥe]

|

[yn]

|

[ɥɛn]

|

[jʊŋ]

|

||||||||

Technically, i, u, ü without a following vowel are finals, not medials, and therefore take the tone marks, but they are more concisely displayed as above. In addition, ê [ɛ] (欸; 誒) and syllabic nasals m (呒, 呣), n (嗯, 唔), ng (嗯, 𠮾) are used as interjections or in neologisms; for example, pinyin defines the names of several pinyin letters using -ê finals.

According to the Scheme for the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet, ng can be abbreviated with the shorthand ŋ. However, this shorthand is rarely used due to difficulty of entering it on computers.

| Pinyin | IPA | Form with zero initial | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| -i | [ɹ̩~z̩], [ɻ̩~ʐ̩] | (N/A) | -i is a buzzed continuation of the consonant following z-, c-, s-, zh-, ch-, sh- or r-. In all other cases, -i has the sound of bee. |

| a | [a] | a | like English father, but a bit more fronted |

| e | [ɤ] , [ə][a] | e | a back, unrounded vowel (similar to English duh, but not as open). Pronounced as a sequence [ɰɤ]. |

| ai | [ai̯] | ai | like English eye, but a bit lighter |

| ei | [ei̯] | ei | as in hey |

| ao | [au̯] | ao | approximately as in cow; the a is much more audible than the o |

| ou | [ou̯] | ou | as in North American English so |

| an | [an] | an | like British English ban, but more central |

| en | [ən] | en | as in taken |

| ang | [aŋ] | ang | as in German Angst. (Starts with the vowel sound in father and ends in the velar nasal; like song in some dialects of American English) |

| eng | [əŋ] | eng | like e in en above but with ng appended |

| ong | [ʊŋ]~[o̞ʊŋ][a] | (weng) | starts with the vowel sound in book and ends with the velar nasal sound in sing. Varies between [oŋ] and [uŋ] depending on the speaker. |

| er | [aɚ̯]~[əɹ][a] | er | Similar to the sound in bar in English. Can also be pronounced [ɚ] depending on the speaker. |

| Finals beginning with i- (y-) | |||

| i | [i] | yi | like English bee |

| ia | [ja] | ya | as i + a; like English yard |

| ie | [je] | ye | as i + ê where the e (compare with the ê interjection) is pronounced shorter and lighter |

| iao | [jau̯] | yao | as i + ao |

| iu | [jou̯] | you | as i + ou |

| ian | [jɛn] | yan | as i + an; like English yen. Varies between [jen] and [jan] depending on the speaker. |

| in | [in] | yin | as i + n |

| iang | [jaŋ] | yang | as i + ang |

| ing | [iŋ] | ying | as i + ng |

| iong | [jʊŋ] | yong | as i + ong. Varies between [joŋ] and [juŋ] depending on the speaker. |

| Finals beginning with u- (w-) | |||

| u | [u] | wu | like English oo |

| ua | [wa] | wa | as u + a |

| uo/o | [wo] | wo | as u + o where the o (compare with the o interjection) is pronounced shorter and lighter (spelled as o after b, p, m or f) |

| uai | [wai̯] | wai | as u + ai, as in English why |

| ui | [wei̯] | wei | as u + ei, as in English way |

| uan | [wan] | wan | as u + an |

| un | [wən] | wen | as u + en; as in English won |

| uang | [waŋ] | wang | as u + ang |

| (ong) | [wəŋ] | weng | as u + eng |

| Finals beginning with ü- (yu-) | |||

| ü | [y] | yu | as in German über or French lune (pronounced as English ee with rounded lips; spelled as u after j, q or x) |

| üe | [ɥe] | yue | as ü + ê where the e (compare with the ê interjection) is pronounced shorter and lighter (spelled as ue after j, q or x) |

| üan | [ɥɛn] | yuan | as ü + an. Varies between [ɥen] and [ɥan] depending on the speaker (spelled as uan after j, q or x) |

| ün | [yn] | yun | as ü + n (spelled as un after j, q or x) |

| Interjections | |||

| ê | [ɛ] | ê | as in bet |

| o | [ɔ] | o | approximately as in British English office; the lips are much more rounded |

| io | [jɔ] | yo | as i + o |

The ⟨ü⟩ sound

[edit]An umlaut is added to ⟨u⟩ when it occurs after the initials ⟨l⟩ and ⟨n⟩ when necessary in order to represent the sound [y]. This is necessary in order to distinguish the front high rounded vowel in lü (e.g. 驴; 驢; 'donkey') from the back high rounded vowel in lu (e.g. 炉; 爐; 'oven'). Tonal markers are placed above the umlaut, as in lǘ.

However, the ü is not used in the other contexts where it could represent a front high rounded vowel, namely after the letters j, q, x, and y. For example, the sound of the word for 'fish' (鱼; 魚) is transcribed in pinyin simply as yú, not as yǘ. This practice is opposed to Wade–Giles, which always uses ü, and Tongyong Pinyin, which always uses yu. Whereas Wade–Giles needs the umlaut to distinguish between chü (pinyin ju) and chu (pinyin zhu), this ambiguity does not arise with pinyin, so the more convenient form ju is used instead of jü. Genuine ambiguities only happen with nu/nü and lu/lü, which are then distinguished by an umlaut.

Many fonts or output methods do not support an umlaut for ü or cannot place tone marks on top of ü. Likewise, using ü in input methods is difficult because it is not present as a simple key on many keyboard layouts. For these reasons v is sometimes used instead by convention. For example, it is common for cellphones to use v instead of ü. Additionally, some stores in China use v instead of ü in the transliteration of their names. The drawback is that there are no tone marks for the letter v.

This also presents a problem in transcribing names for use on passports, affecting people with names that consist of the sound lü or nü, particularly people with the surname 吕 (Lǚ), a fairly common surname, particularly compared to the surnames 陆 (Lù), 鲁 (Lǔ), 卢 (Lú) and 路 (Lù). Previously, the practice varied among different passport issuing offices, with some transcribing as "LV" and "NV" while others used "LU" and "NU". On 10 July 2012, the Ministry of Public Security standardized the practice to use "LYU" and "NYU" in passports.[18][19]

Although nüe written as nue, and lüe written as lue are not ambiguous, nue or lue are not correct according to the rules; nüe and lüe should be used instead. However, some Chinese input methods support both nve/lve (typing v for ü) and nue/lue.

Tones

[edit]

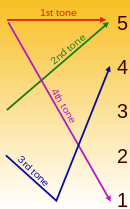

The pinyin system also uses four diacritics to mark the tones of Mandarin.[20] In the pinyin system, four main tones of Mandarin are shown by diacritics: ā, á, ǎ, and à.[21] There is no symbol or diacritic for the neutral tone: a. The diacritic is placed over the letter that represents the syllable nucleus, unless that letter is missing. Tones are used in Hanyu Pinyin symbols, and they do not appear in Chinese characters.

Tones are written on the finals of Chinese pinyin. If the tone mark is written over an i, then it replaces the tittle, as in yī.

- The first tone (flat or high-level tone) is represented by a macron ⟨ˉ⟩ added to the pinyin vowel:

- ā ē ê̄ ī ō ū ǖ Ā Ē Ê̄ Ī Ō Ū Ǖ

- The second tone (rising or high-rising tone) is denoted by an acute accent ⟨ˊ⟩:

- á é ế í ó ú ǘ Á É Ế Í Ó Ú Ǘ

- The third tone (falling-rising or low tone) is marked by a caron ⟨ˇ⟩:

- ǎ ě ê̌ ǐ ǒ ǔ ǚ Ǎ Ě Ê̌ Ǐ Ǒ Ǔ Ǚ

- The fourth tone (falling or high-falling tone) is represented by a grave accent ⟨ˋ⟩:

- à è ề ì ò ù ǜ À È Ề Ì Ò Ù Ǜ

- The fifth tone (neutral tone) is represented by a normal vowel without any accent mark:

- a e ê i o u ü A E Ê I O U Ü

In dictionaries, neutral tone may be indicated by a dot preceding the syllable—e.g. ·ma. When a neutral tone syllable has an alternative pronunciation in another tone, a combination of tone marks may be used: zhī·dào (知道) may be pronounced either zhīdào or zhīdao.[22]

Numbers

[edit]Before the advent of computers, many typewriter fonts did not contain vowels with macron or caron diacritics. Tones were thus represented by placing a tone number at the end of individual syllables. For example, tóng is written tong2. Each tone can be denoted with its numeral the order listed above. The neutral tone can either be denoted with no numeral, with 0, or with 5.

| Tone | Examples | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

ma˥ |

| 2 |

|

ma˧˥ |

| 3 |

|

ma˨˩˦ |

| 4 |

|

ma˥˩ |

| Neutral |

|

ma |

Placement and omission

[edit]Briefly, tone marks should always be placed in the order a, o, e, i, u, ü, with the only exception being iu, where the tone mark is placed on the u instead. Pinyin tone marks appear primarily above the syllable nucleus—e.g. as in kuài, where k is the initial, u the medial, a the nucleus, and i is the coda. There is an exception for syllabic nasals like /m/, where the nucleus of the syllable is a consonant: there, the diacritic will be carried by a written dummy vowel.

When the nucleus is /ə/ (written e or o), and there is both a medial and a coda, the nucleus may be dropped from writing. In this case, when the coda is a consonant n or ng, the only vowel left is the medial i, u, or ü, and so this takes the diacritic. However, when the coda is a vowel, it is the coda rather than the medial which takes the diacritic in the absence of a written nucleus. This occurs with syllables ending in -ui (from wei: wèi → -uì) and in -iu (from you: yòu → -iù). That is, in the absence of a written nucleus the finals have priority for receiving the tone marker, as long as they are vowels; if not, the medial takes the diacritic.

An algorithm to find the correct vowel letter (when there is more than one) is as follows:

- If there is an a or an e, it will take the tone mark

- If there is an ou, then the o takes the tone mark

- Otherwise, the second vowel takes the tone mark

Worded differently,

- If there is an a, e, or o, it will take the tone mark; in the case of ao, the mark goes on the a

- Otherwise, the vowels are -iu or -ui, in which case the second vowel takes the tone mark

The above can be summarized as the following table. The vowel letter taking the tone mark is indicated by the fourth-tone mark.

| -a | -e | -i | -o | -u | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a- | ài | ào | |||

| e- | èi | ||||

| i- | ià, iào | iè | iò | iù | |

| o- | òu | ||||

| u- | uà, uài | uè | uì | uò | |

| ü- | (üà) | üè | |||

- ^ a b c d e f g h i for Taipei Mandarin

- ^ a b Y and w are equivalent to the semivowel medials i, u, and ü (see below). They are spelled differently when there is no initial consonant in order to mark a new syllable: fanguan is fan-guan, while fangwan is fang-wan (and equivalent to *fang-uan). With this convention, an apostrophe only needs to be used to mark an initial a, e, or o: Xi'an (two syllables: [ɕi.an]) vs. xian (one syllable: [ɕi̯ɛn]). In addition, y and w are added to fully vocalic i, u, and ü when these occur without an initial consonant, so that they are written yi, wu, and yu. Some Mandarin speakers do pronounce a [j] or [w] sound at the beginning of such words—that is, yi [i] or [ji], wu [u] or [wu], yu [y] or [ɥy],—so this is an intuitive convention. See below for a few finals which are abbreviated after a consonant plus w/u or y/i medial: wen → C+un, wei → C+ui, weng → C+ong, and you → Q+iu.

Tone sandhi

[edit]Tone sandhi is not ordinarily reflected in pinyin spelling.

Spacing, capitalization, and punctuation

[edit]Standard Chinese has many polysyllabic words. Like in other writing systems using the Latin alphabet, spacing in pinyin is officially based on word boundaries. However, there are often ambiguities in partitioning a word. The Basic Rules of the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet Orthography were put into effect in 1988 by the National Educational and National Language commissions.[23] These rules became a GB recommendation in 1996,[23] and were last updated in 2012.[24]

In practice, however, published materials in China now often space pinyin syllable by syllable. According to Victor H. Mair, this practice became widespread after the Script Reform Committee, previously under direct control of the State Council, had its power greatly weakened in 1985 when it was renamed the State Language Commission and placed under the Ministry of Education.[25] Mair claims that proponents of Chinese characters in the educational bureacracy “became alarmed that word-based pinyin was becoming a de facto alternative to Chinese characters as a script for writing Mandarin and demanded that all pinyin syllables be written separately.”[26]

Comparison with other orthographies

[edit]Pinyin superseded older romanization systems such as Wade–Giles and postal romanization, and replaced bopomofo as the method of Chinese phonetic instruction in mainland China. The ISO adopted pinyin as the standard romanization for modern Chinese in 1982 (ISO 7098:1982, superseded by ISO 7098:2015). The United Nations followed suit in 1986.[5][27] It has also been accepted by the government of Singapore, the United States's Library of Congress, the American Library Association, and many other international institutions.[28][failed verification] Pinyin assigns some Latin letters sound values which are quite different from those of most languages. This has drawn some criticism as it may lead to confusion when uninformed speakers apply either native or English assumed pronunciations to words. However, this problem is not limited only to pinyin, since many languages that use the Latin alphabet natively also assign different values to the same letters. A recent study on Chinese writing and literacy concluded, "By and large, pinyin represents the Chinese sounds better than the Wade–Giles system, and does so with fewer extra marks."[29]

As pinyin is a phonetic writing system for modern Standard Chinese, it is not designed to replace characters for writing Literary Chinese, the standard written language prior to the early 1900s. In particular, Chinese characters retain semantic cues that help distinguish differently pronounced words in the ancient classical language that are now homophones in Mandarin. Thus, Chinese characters remain indispensable for recording and transmitting the corpus of Chinese writing from the past.

Pinyin is not designed to transcribe varieties other than Standard Chinese, which is based on the phonological system of Beijing Mandarin. Other romanization schemes have been devised to transcribe those other Chinese varieties, such as Jyutping for Cantonese and Pe̍h-ōe-jī for Hokkien.

Comparison charts

[edit]| IPA | a | ɔ | ɛ | ɤ | ai | ei | au | ou | an | ən | aŋ | əŋ | ʊŋ | aɹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | a | o | ê | e | ai | ei | ao | ou | an | en | ang | eng | ong | er |

| Tongyong Pinyin | ||||||||||||||

| Wade–Giles | eh | ê/o | ên | êng | ung | êrh | ||||||||

| Bopomofo | ㄚ | ㄛ | ㄝ | ㄜ | ㄞ | ㄟ | ㄠ | ㄡ | ㄢ | ㄣ | ㄤ | ㄥ | ㄨㄥ | ㄦ |

| example | 阿 | 喔 | 誒 | 俄 | 艾 | 黑 | 凹 | 偶 | 安 | 恩 | 昂 | 冷 | 中 | 二 |

| IPA | i | je | jou | jɛn | in | iŋ | jʊŋ | u | wo | wei | wən | wəŋ | y | ɥe | ɥɛn | yn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | yi | ye | you | yan | yin | ying | yong | wu | wo/o | wei | wen | weng | yu | yue | yuan | yun |

| Tongyong Pinyin | wun | wong | ||||||||||||||

| Wade–Giles | i/yi | yeh | yu | yen | yung | wên | wêng | yü | yüeh | yüan | yün | |||||

| Bopomofo | ㄧ | ㄧㄝ | ㄧㄡ | ㄧㄢ | ㄧㄣ | ㄧㄥ | ㄩㄥ | ㄨ | ㄨㄛ/ㄛ | ㄨㄟ | ㄨㄣ | ㄨㄥ | ㄩ | ㄩㄝ | ㄩㄢ | ㄩㄣ |

| example | 一 | 也 | 又 | 言 | 音 | 英 | 用 | 五 | 我 | 位 | 文 | 翁 | 玉 | 月 | 元 | 雲 |

| IPA | p | pʰ | m | fəŋ | tjou | twei | twən | tʰɤ | ny | ly | kɤɹ | kʰɤ | xɤ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | b | p | m | feng | diu | dui | dun | te | nü | lü | ge | ke | he |

| Tongyong Pinyin | fong | diou | duei | nyu | lyu | ||||||||

| Wade–Giles | p | pʻ | fêng | tiu | tui | tun | tʻê | nü | lü | ko | kʻo | ho | |

| Bopomofo | ㄅ | ㄆ | ㄇ | ㄈㄥ | ㄉㄧㄡ | ㄉㄨㄟ | ㄉㄨㄣ | ㄊㄜ | ㄋㄩ | ㄌㄩ | ㄍㄜ | ㄎㄜ | ㄏㄜ |

| example | 玻 | 婆 | 末 | 封 | 丟 | 兌 | 頓 | 特 | 女 | 旅 | 歌 | 可 | 何 |

| IPA | tɕjɛn | tɕjʊŋ | tɕʰin | ɕɥɛn | ʈʂɤ | ʈʂɨ | ʈʂʰɤ | ʈʂʰɨ | ʂɤ | ʂɨ | ɻɤ | ɻɨ | tsɤ | tswo | tsɨ | tsʰɤ | tsʰɨ | sɤ | sɨ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | jian | jiong | qin | xuan | zhe | zhi | che | chi | she | shi | re | ri | ze | zuo | zi | ce | ci | se | si |

| Tongyong Pinyin | jyong | cin | syuan | jhe | jhih | chih | shih | rih | zih | cih | sih | ||||||||

| Wade–Giles | chien | chiung | chʻin | hsüan | chê | chih | chʻê | chʻih | shê | shih | jê | jih | tsê | tso | tzŭ | tsʻê | tzʻŭ | sê | ssŭ |

| Bopomofo | ㄐㄧㄢ | ㄐㄩㄥ | ㄑㄧㄣ | ㄒㄩㄢ | ㄓㄜ | ㄓ | ㄔㄜ | ㄔ | ㄕㄜ | ㄕ | ㄖㄜ | ㄖ | ㄗㄜ | ㄗㄨㄛ | ㄗ | ㄘㄜ | ㄘ | ㄙㄜ | ㄙ |

| example | 件 | 窘 | 秦 | 宣 | 哲 | 之 | 扯 | 赤 | 社 | 是 | 惹 | 日 | 仄 | 左 | 字 | 策 | 次 | 色 | 斯 |

| IPA | ma˥˥ | ma˧˥ | ma˨˩˦ | ma˥˩ | ma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | mā | má | mǎ | mà | ma |

| Tongyong Pinyin | ma | må | |||

| Wade–Giles | ma1 | ma2 | ma3 | ma4 | ma |

| Bopomofo | ㄇㄚ | ㄇㄚˊ | ㄇㄚˇ | ㄇㄚˋ | ˙ㄇㄚ |

| example (Chinese characters) | 媽 | 麻 | 馬 | 罵 | 嗎 |

Typography and encoding

[edit]Based on the "Chinese Romanization" section of ISO 7098:2015, pinyin tone marks should use the symbols from Combining Diacritical Marks, as opposed by the use of Spacing Modifier Letters in bopomofo. Lowercase letters with tone marks are included in GB 2312 and their uppercase counterparts are included in JIS X 0212;[30] thus Unicode includes all the common accented characters from pinyin.[31] Other punctuation mark and symbols in Chinese are to use the equivalent symbol in English noted in to GB 15834.

According to GB 16159, all accented letters are required to have both uppercase and lowercase characters as per their normal counterparts.

- a.^ Yellow cells indicate that there are no single Unicode character for that letter; the character shown here uses Combining Diacritical Mark characters to display the letter.[31]

- b.^ Grey cells indicate that Xiandai Hanyu Cidian does not include pinyin with that specific letter.[31]

| Letter | First tone | Second tone | Third tone | Fourth tone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combining Diacritical Marks | ̄ (U+0304) | ́ (U+0301) | ̌ (U+030C) | ̀ (U+0300) | |

| Common letters | |||||

| Uppercase | A | Ā (U+0100) | Á (U+00C1) | Ǎ (U+01CD) | À (U+00C0) |

| E | Ē (U+0112) | É (U+00C9) | Ě (U+011A) | È (U+00C8) | |

| I | Ī (U+012A) | Í (U+00CD) | Ǐ (U+01CF) | Ì (U+00CC) | |

| O | Ō (U+014C) | Ó (U+00D3) | Ǒ (U+01D1) | Ò (U+00D2) | |

| U | Ū (U+016A) | Ú (U+00DA) | Ǔ (U+01D3) | Ù (U+00D9) | |

| Ü (U+00DC) | Ǖ (U+01D5) | Ǘ (U+01D7) | Ǚ (U+01D9) | Ǜ (U+01DB) | |

| Lowercase | a | ā (U+0101) | á (U+00E1) | ǎ (U+01CE) | à (U+00E0) |

| e | ē (U+0113) | é (U+00E9) | ě (U+011B) | è (U+00E8) | |

| i | ī (U+012B) | í (U+00ED) | ǐ (U+01D0) | ì (U+00EC) | |

| o | ō (U+014D) | ó (U+00F3) | ǒ (U+01D2) | ò (U+00F2) | |

| u | ū (U+016B) | ú (U+00FA) | ǔ (U+01D4) | ù (U+00F9) | |

| ü (U+00FC) | ǖ (U+01D6) | ǘ (U+01D8) | ǚ (U+01DA) | ǜ (U+01DC) | |

| Rare letters | |||||

| Uppercase | Ê (U+00CA) | Ê̄ (U+00CA U+0304) | Ế (U+1EBE) | Ê̌ (U+00CA U+030C) | Ề (U+1EC0) |

| M | M̄ (U+004D U+0304) | Ḿ (U+1E3E) | M̌ (U+004D U+030C) | M̀ (U+004D U+0300) | |

| N | N̄ (U+004E U+0304) | Ń (U+0143) | Ň (U+0147) | Ǹ (U+01F8) | |

| Lowercase | ê (U+00EA) | ê̄ (U+00EA U+0304) | ế (U+1EBF) | ê̌ (U+00EA U+030C) | ề (U+1EC1) |

| m | m̄ (U+006D U+0304) | ḿ (U+1E3F) | m̌ (U+006D U+030C) | m̀ (U+006D U+0300) | |

| n | n̄ (U+006E U+0304) | ń (U+0144) | ň (U+0148) | ǹ (U+01F9) | |

GBK has mapped two characters ⟨ḿ⟩ and ⟨ǹ⟩ to Private Use Areas in Unicode respectively, thus some fonts (e.g. SimSun) that adhere to GBK include both characters in the Private Use Areas, and some input methods (e.g. Sogou Pinyin) also outputs the Private Use Areas code point instead of the original character. As the superset GB 18030 changed the mappings of ⟨ḿ⟩ and ⟨ǹ⟩, this has caused an issue where the input methods and font files use different encoding standards, and thus the input and output of both characters are mixed up.[31]

| Uppercase | Lowercase | Note | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ĉ (U+0108) | ĉ (U+0109) | Abbreviation of ch | 长; 長 can be spelled as ĉáŋ |

| Ŝ (U+015C) | ŝ (U+015D) | Abbreviation of sh | 伤; 傷 can be spelled as ŝāŋ |

| Ẑ (U+1E90) | ẑ (U+1E91) | Abbreviation of zh | 张; 張 can be spelled as Ẑāŋ |

| Ŋ (U+014A) | ŋ (U+014B) | Abbreviation of ng |

|

Other symbols are used in pinyin are as follows:

| Chinese | Pinyin | Usage | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| U+3002 。 IDEOGRAPHIC FULL STOP | U+002E . FULL STOP | End of sentence | 你好。 Nǐ hǎo. |

|

U+002C , COMMA | Connecting clauses | 你,好吗? Nǐ, hǎo ma? |

| U+2014 — EM DASH (×2) | U+2014 — EM DASH | Division of clauses mid-sentence | 枢纽部分——中央大厅 shūniǔ bùfèn — zhōngyāng dàtīng |

| U+2026 … HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS (×2) | U+2026 … HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS | Redaction of part of a passage | 我…… Wǒ… |

| — | U+00B7 · MIDDLE DOT | Neutral tone marker placed before the syllable | 吗 ·ma |

| U+002D - HYPHEN-MINUS | Hyphenation of abbreviated compounds | 公关 gōng-guān | |

| U+0027 ' APOSTROPHE | Syllable segmentation | 西安 - Xī'ān (compared to 先 - xiān) |

Usage

[edit]

The spelling of Chinese geographical or personal names in pinyin has become the most common way to transcribe them in English. Pinyin has also become the dominant Chinese input method in mainland China, in contrast to Taiwan, where bopomofo is most commonly used.

Families outside of Taiwan who speak Mandarin as a mother tongue use pinyin to help children associate characters with spoken words which they already know. Chinese families outside of Taiwan who speak some other language as their mother tongue use the system to teach children Mandarin pronunciation when learning vocabulary in elementary school.[32]

Since 1958, pinyin has been actively used in adult education as well, making it easier for formerly illiterate people] to continue with self-study after a short period of pinyin literacy instruction.[33]

Pinyin has become a tool for many foreigners to learn Mandarin pronunciation, and is used to explain both the grammar and spoken Mandarin coupled with Chinese characters. Books containing both Chinese characters and pinyin are often used by foreign learners of Chinese. Pinyin's role in teaching pronunciation to foreigners and children is similar in some respects to furigana-based books with hiragana letters written alongside kanji (directly analogous to bopomofo) in Japanese, or fully vocalised texts in Arabic.

The tone-marking diacritics are commonly omitted in popular news stories and even in scholarly works, as well as in the traditional Mainland Chinese Braille system, which is similar to pinyin, but meant for blind readers.[34] This results in some degree of ambiguity as to which words are being represented.

Computer input

[edit]Simple computer systems, sometimes only able to use simple character systems for text, such as the 7-bit ASCII standard—essentially the 26 Latin letters, 10 digits, and punctuation marks—long provided a convincing argument for using unaccented pinyin instead of diacritical pinyin or Chinese characters. Today, however, most computer systems are able to display characters from Chinese and many other writing systems as well, and have them entered with a Latin keyboard using an input method editor. Alternatively, some touchscreen devices allow users to input characters graphically by writing with a stylus, with concurrent online handwriting recognition.

Pinyin with accents can be entered with the use of special keyboard layouts or various other utilities.

Sorting techniques

[edit]Chinese text can be sorted by its pinyin representation, which is often useful for looking up words whose pronunciations are known, but not whose character forms are not known. Chinese characters and words can be sorted for convenient lookup by their Pinyin expressions alphabetically,[35] according to their inherited order originating with the ancient Phoenicians. Identical syllables are then further sorted by tone number, ascending, with neutral tones placed last.

Words of multiple characters can be sorted in two different ways,[36] either per character, as is used in the Xiandai Hanyu Cidian, or by the whole word's string, which is only then sorted by tone. This method is used in the ABC Chinese–English Dictionary.

By region

[edit]Taiwan

[edit]Between October 2002 and January 2009, Taiwan used Tongyong Pinyin, a domestic modification of Hanyu Pinyin, as its official romanization system. Thereafter, it began to promote the use of Hanyu Pinyin instead. Tongyong Pinyin was designed to romanize varieties spoken on the island in addition to Standard Chinese. The ruling Kuomintang (KMT) party resisted its adoption, preferring the system by then used in mainland China and internationally. Romanization preferences quickly became associated with issues of national identity. Preferences split along party lines: the KMT and its affiliated parties in the Pan-Blue Coalition supported the use of Hanyu Pinyin while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and its allies in the Pan-Green Coalition favored the use of Tongyong Pinyin.

Today, many street signs in Taiwan use Tongyong Pinyin or derived romanizations,[37] but some use Hanyu Pinyin–derived romanizations. It is not unusual to see spellings on street signs and buildings derived from the older Wade–Giles, MPS2 and other systems. Attempts to make Hanyu Pinyin standard in Taiwan have had uneven success, with most place and proper names remaining unaffected, including all major cities. Personal names on Taiwanese passports honor the choices of Taiwanese citizens, who can choose Wade–Giles, Hakka, Hoklo, Tongyong, aboriginal, or pinyin.[38] Official use of pinyin is controversial, as when pinyin use for a metro line in 2017 provoked protests, despite government responses that "The romanization used on road signs and at transportation stations is intended for foreigners... Every foreigner learning Mandarin learns Hanyu pinyin, because it is the international standard...The decision has nothing to do with the nation's self-determination or any ideologies, because the key point is to ensure that foreigners can read signs."[39]

Singapore

[edit]Singapore implemented Hanyu Pinyin as the official romanization system for Mandarin in the public sector starting in the 1980s, in conjunction with the Speak Mandarin Campaign.[40] Hanyu Pinyin is also used as the romanization system to teach Mandarin Chinese at schools.[41] While adoption has been mostly successful in government communication, placenames, and businesses established in the 1980s and onward, it continues to be unpopular in some areas, most notably for personal names and vocabulary borrowed from other varieties of Chinese already established in the local vernacular.[40] In these situations, romanization continues to be based on the Chinese language variety it originated from, especially the three largest Chinese varieties traditionally spoken in Singapore: Hokkien, Teochew, and Cantonese.

Special names

[edit]In accordance to the Regulation of Phonetic Transcription in Hanyu Pinyin Letters of Place Names in Minority Nationality Languages (少数民族语地名汉语拼音字母音译转写法; 少數民族語地名漢語拼音字母音譯寫法) promulgated in 1976, place names in non-Han languages like Mongolian, Uyghur, and Tibetan are also officially transcribed using pinyin in a system adopted by the State Administration of Surveying and Mapping and Geographical Names Committee known as SASM/GNC romanization. The pinyin letters (26 Roman letters, plus ⟨ü⟩ and ⟨ê⟩) are used to approximate the non-Han language in question as closely as possible. This results in spellings that are different from both the customary spelling of the place name, and the pinyin spelling of the name in Chinese:

| Customary | Official pinyin | Characters |

|---|---|---|

| Shigatse | Xigazê | 日喀则; 日喀則; Rìkāzé |

| Urumchi | Ürümqi | 乌鲁木齐; 烏魯木齊; Wūlǔmùqí |

| Lhasa | Lhasa | 拉萨; 拉薩; Lāsà |

| Hohhot | Hohhot | 呼和浩特; Hūhéhàotè |

| Golmud | Golmud | 格尔木; 格爾木; Gé'ěrmù |

| Qiqihar | Qiqihar | 齐齐哈尔; 齊齊哈爾; Qíqíhā'ěr |

See also

[edit]- Combining character

- Comparison of Chinese transcription systems

- Cyrillization of Chinese

- Romanization of Japanese

- Transcription into Chinese characters

- Two-cell Chinese Braille

- Chinese word-segmented writing

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Sin, Kiong Wong (2012). Confucianism, Chinese History and Society. World Scientific. p. 72. ISBN 978-9-814-37447-7. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Brockey, Liam Matthew (2009). Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724. Harvard University Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-674-02881-4. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ a b Chan, Wing-tsit; Adler, Joseph (2013). Sources of Chinese Tradition. Columbia University Press. pp. 303–304. ISBN 978-0-231-51799-7. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Ao, Benjamin (1997). "History and Prospect of Chinese Romanization". Chinese Librarianship: An International Electronic Journal. 4.

- ^ a b c Fox (2017).

- ^ "Father of pinyin". China Daily. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009. Reprinted in part as Simon, Alan (21–27 January 2011). "Father of Pinyin". China Daily Asia Weekly. Hong Kong. Xinhua. p. 20.

- ^ Dwyer, Colin (14 January 2017). "Obituary: Zhou Youguang, Architect of a Bridge Between Languages, Dies at 111". NPR. National Public Radio. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ a b Branigan (2008).

- ^ Hessler, Peter (8 February 2004). "Oracle Bones". The New Yorker. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Rohsenow (2004), p. 23.

- ^ Wang (1995).

- ^ a b "Hanyu Pinyin system turns 50". Straits Times. 11 February 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ Wiedenhof, Jeroen (2004). Purpose and effect in the transcription of Mandarin (PDF). Proceedings of the International Conference on Chinese Studies 2004 漢學研究國際學術研討會論文集. National Yunlin University of Science and Technology. pp. 387–402. ISBN 9-860-04011-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

In the Cold War era, the use of this system outside China was typically regarded as a political statement, or a deliberate identification with the Chinese communist regime. (p390)

- ^ Terry, Edith (2002). How Asia got rich: Japan, China and the Asian miracle. A Pacific Basin Institute book. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe. p. 632–633. ISBN 978-0-765-60355-5.

- ^ "Times Due To Revise Its Chinese Spelling". The New York Times. 4 February 1979. p. 10. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ GB/T 16159 (2012).

- ^ Shea, Marilyn. "Pinyin / Ting - The Chinese Experience". hua.umf.maine.edu. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ^ Huang, Rong. 公安部最新规定 护照上的"ü"规范成"YU" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ Li, Zhiyan. "吕"拼音到怎么写? 公安部称应拼写成"LYU" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ Wang, Qiuying; Andrews, Jean F. (2021). "Chinese Pinyin: Overview, History and Use in Language Learning for Young Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students in China". American Annals of the Deaf. 166 (4): 446–461. doi:10.1353/aad.2021.0038. ISSN 1543-0375. PMID 35185033. S2CID 247010548.

- ^ Chang, Yufen (9 October 2018). "How pinyin tone formats and character orthography influence Chinese learners' tone acquisition". Chinese as a Second Language Research. 7 (2): 195–219. doi:10.1515/caslar-2018-0008. ISSN 2193-2263. S2CID 57998920.

- ^ GB/T 16159 (2012), §7.3.

- ^ a b "Basic Rules of the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet Orthography". Qingdao Vocational and Technical College of Hotel Management (in Chinese). 10 April 2014. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Release of the National Standard Basic Rules of the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet Orthography". China Education and Research Network (in Chinese). 20 July 2012. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Mair, Victor (11 April 2019). "First grade science card: Pinyin degraded". Language Log.

- ^ Mair, Victor (15 August 2012). Comment on "Words in Mandarin: twin kle twin kle lit tle star". Language Log. 15 August 2012.

- ^ Lin Mei-chun (8 October 2000). "Official challenges romanization". Taipei Times.

- ^ Ao, Benjamin (1 December 1997). "History and Prospect of Chinese Romanization". Chinese Librarianship: An International Electronic Journal (4). Internet Chinese Librarians Club. ISSN 1089-4667. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ Taylor & Taylor (2014), p. 124.

- ^ "Chapter 7: Europe-I". Unicode 14.0 Core Specification (PDF) (14.0 ed.). Mountain View, CA: Unicode. 2021. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-936-21329-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Liu, Eric Q. "The Type—Wǒ ài pīnyīn!". The Type. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Snowling & Hulme (2005), pp. 320–322.

- ^ Price (2005), pp. 206–208.

- ^ "Braille's invention still a boon to visually impaired Chinese readers". South China Morning Post. 5 January 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

... mainland Chinese Braille for standard Mandarin, and Taiwanese Braille for Taiwanese Mandarin are phonetically based ... tone (generally omitted for Mandarin systems)

- ^ Wang & Zou (2003), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Su Peicheng (苏培成) (2014). 现代汉字学纲要 [Essentials of Modern Chinese Characters] (in Chinese) (3rd ed.). Beijing: The Commercial Press. pp. 183–207. ISBN 978-7-100-10440-1.

- ^ Liu Wanjun (劉婉君) (15 October 2018). 路牌改通用拼音? 南市府:已採用多年. Liberty Times (in Chinese). Retrieved 28 July 2019. 基進黨台南市東區市議員參選人李宗霖今天指出,台南市路名牌拼音未統一、音譯錯誤等,建議統一採用通用拼音。對此,台南市政府交通局回應,南市已實施通用拼音多年,將全面檢視路名牌,依現行音譯方式進行校對改善。

- ^ Everington, Keoni (15 August 2019). "Taiwan passport can now include names in Hoklo, Hakka, indigenous languages". Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Lin, Sean (11 January 2017). "Groups protest use of Hanyu pinyin for new MRT line". Taipei Times. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b Bockhorst-Heng & Lee (2007), p. 3.

- ^ Chan (2016), p. 485.

Works cited

[edit]- 汉语拼音方案 [Scheme for the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet] (in Chinese). Chinese Script Reform Committee. 1982 [1958]. ISO 7098:1982 – via Wikisource.

- 汉语拼音正词法基本规则 [Basic rules of the Chinese phonetic alphabet orthography] (in Chinese). National Standards of the People's Republic of China. 29 June 2012. GB/T 16159-2012 – via pinyin.info.

- Bockhorst-Heng, Wendy; Lee, Lionel (November 2007). "Language Planning in Singapore: On Pragmatism, Communitarianism and Personal Names". Current Issues in Language Planning.

- Branigan, Tania (21 February 2008). "Sound Principles". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- Chan, Sin-Wai, ed. (2016). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Chinese Language. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-38249-2.

- Fox, Margalit (14 January 2017). "Zhou Youguang, Who Made Writing Chinese as Simple as ABC, Dies at 111". The New York Times.

- Price, R. F. (2005). Education in Modern China. China: History, Philosophy, Economics. Vol. 23 (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36167-2.

- Rohsenow, John S. (2004). "Fifty Years of Script and Written Language Reform in the P.R.C.: The Genesis of the Language Law of 2001". In Zhou, Minglang; Sun, Hongkai (eds.). Language Policy in the People’s Republic of China. Springer. pp. 21–43. ISBN 978-1-402-08038-8.

- Snowling, Margaret J.; Hulme, Charles (2005). The Science of Reading. Blackwell Handbooks of Developmental Psychology. Vol. 17. Blackwell. ISBN 1-405-11488-6.

- Sybesma, Rint, ed. (2015). Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics Online. Brill. doi:10.1163/2210-7363-ecll-all. ISSN 2210-7363.

- Wipperman, Dorothea. "Transcription Systems: Hànyǔ pīnyīn 漢語拼音". In Sybesma (2015).

- Taylor, Insup; Taylor, M. Martin (2014) [1995]. Writing and Literacy in Chinese, Korean, and Japanese. Studies in Written Language and Literacy. Vol. 14 (Rev. ed.). John Benjamins. ISBN 978-9-027-21794-3.

- Tsu, Jing (2022). "When "Peking" Became "Beijing"". Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution That Made China Modern. New York: Riverhead. pp. 171–213. ISBN 978-0-735-21472-9.

- Wang Jun (王均) (1995). 当代中國的文字改革 [Writing System Reform in Contemporary China] (in Chinese). Beijing: Contemporary Chinese Publishing House. ISBN 978-7-800-92298-5.

- Wang Ning (王寧) Zou Xiaoli (鄒曉麗) (2003). 工具書 [Reference Books] (in Chinese). Hong Kong: Peace Book. pp. 27–28. ISBN 9-622-38363-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Gao, Johnson K. (2005). Pinyin shorthand: a bilingual handbook. Jack Sun. ISBN 978-1-599-71251-2.

- Yin Binyong (尹斌庸) Felley, Mary (1990). 汉语拼音和正词法 [Chinese romanization: pronunciation and orthography]. Sinolingua. ISBN 978-7-800-52148-5.

External links

[edit]- Chinese phonetic alphabet spelling rules for Chinese names—The official standard GB/T 28039–2011 in Chinese. PDF version from the Chinese Ministry of Education (in Chinese)

- HTML version (in Chinese)

| Major groups |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard forms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phonology | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grammar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Idioms | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Input | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literary forms |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scripts |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||