| Lou Thesz | |

|---|---|

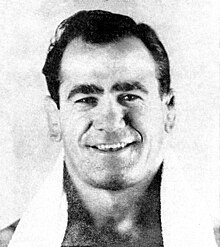

Thesz in 1953 | |

| Birth name | Aloysius Martin Thesz |

| Born | April 24, 1916 Banat, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | April 28, 2002 (aged 86) Orlando, Florida, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Complications caused by Triple bypass surgery |

| Children | 3 |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Ring name(s) | Lou Thesz |

| Billed height | 6 ft 2 in (188 cm)[1] |

| Billed weight | 225 lb (102 kg)[1] |

| Billed from | St. Louis, Missouri[1] |

| Trained by | Ad Santel[1] Ed Lewis[1] George Tragos[1] Ray Steele[1] |

| Debut | 1932[2] |

| Retired | 1990 |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1944–1946 |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Lou Thesz | |

|---|---|

| 3rd President of the Cauliflower Alley Club | |

| In office 1992–2000 | |

| Preceded by | Archie Moore |

| Succeeded by | Red Bastien |

| Part of a series on |

| Professional wrestling |

|---|

|

Aloysius Martin Thesz (April 24, 1916 – April 28, 2002), known by the ring name Lou Thesz, was an American professional wrestler. Considered to be one of the last true shooters (legitimate wrestlers) in professional wrestling[2][3] and described as the "quintessential athlete" and a "polished warrior who could break a man in two if pushed the wrong way",[4] Thesz is widely regarded as one of the greatest wrestlers and wrestling world champions in history, and possibly the last globally accepted world champion.[5][6]

Thesz was a three-time NWA World Heavyweight Champion and held the championship for a combined total of ten years, three months and nine days (3,749 days) – longer than anyone else in history. In Japan, Thesz was known as the "God of Wrestling'" (like his Belgian counterpart, Karl Gotch) and was called "Tetsujin", which means "Ironman", in respect for his speed, conditioning and expertise in catch wrestling.[7] Alongside Karl Gotch and Billy Robinson, Thesz later helped train young Japanese wrestlers and mixed martial artists in catch wrestling.[8]

A successful amateur wrestler in his youth and an ardent supporter of the sport in his later years, he helped establish, in addition to being a member of its inaugural class, the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame, which honors successful professional wrestlers with a strong amateur wrestling background, and is a charter member of several other halls of fame, including: WCW, Wrestling Observer Newsletter, Professional Wrestling and WWE's Legacy Wing.

Alonysius Martin Thesz was born in Banat, Michigan on April 24, 1916.[2] His father, Martin, was a working-class shoemaker of Hungarian and German descent; his mother, Katherine (née Schultz), also of German descent, hailed from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His family moved to St. Louis in Missouri when he was a young boy.[2] Thesz and his three sisters grew up speaking German at home and he did not start learning English until he entered kindergarten at age five. Hungarian was also spoken in the Thesz household but the children did not learn it. In addition to public school, he also had to attend German school every Saturday until he was eight. He was fluent in German and English.[9]

Thesz's father was a national Greco-Roman wrestling middleweight champion in his native Hungary and introduced Lou to the sport as a young boy. At eight years old, Lou began a tough and thorough education in Greco-Roman wrestling under his father, which provided the fundamentals for his later success. He trained in Greco-Roman wrestling under the guidance of his father for several years until transitioning to folkstyle wrestling in high school, where he was a successful competitor on his school team. He also trained in boxing as a teenager. Thesz dropped out of high school by age 14 to work at his father's shoe repair business and began training in freestyle wrestling at Cleveland High School due to his father knowing the wrestling coaches. He quickly became an accomplished freestyle wrestler, competing in city-wide intramurals and regional tournaments in the 160 lb division. At aged 16, Thesz then gained further training in freestyle wrestling under John Zastro. Thesz credited Zastro for elevating his wrestling and became his regular sparring partner. Thesz won several amateur titles and became one of the most dominant freestyle wrestlers of his weight class in the county, and caught the eye of Tom Packs, a professional wrestling promoter in St. Louis. Packs met with Thesz and asked if he wanted to wrestle professionally and Thesz accepted. Thesz later said he would have continued his amateur career had he not been asked.[9] Packs sent Lou to George Tragos for further coaching.

George Tragos, a feared Greek Olympic freestyle wrestler, catch wrestler (also known as 'hooking' during Thesz's time) and wrestling coach at the University of Missouri, took a liking to Thesz and respected his willingness to work hard and follow instruction. He trained under the watchful eye of Tragos for nearly four years at the National Gym in St. Louis.[10] Tragos, who had a well-deserved reputation as a dangerous catch wrestler, decried the emerging performance-related aspects of the sport and instead coached young men to be true, authentic professional wrestlers.[11] Tragos specifically taught Thesz submission wrestling and how to wrestle from the bottom. Thesz remembered Tragos saying, "any fool can start on top. If you start at the bottom, you learn to wrestle." Ray Steele also served as a coach and mentor to Thesz during this time.[12][13]

Thesz also studied under German-born catch wrestler Ad Santel, who was known for his feud with the Kodokan judo school.[14] Thesz studied under Santel for up to five days every week during a 6-month stay in California and remembered it being the "most intensive training period of my life". Throughout his career, Thesz continued to train under Santel whenever he was in the California area. The training he received under Santel would help establish Thesz as one of the most dangerous grapplers in the world.[15]

Thesz later met legendary former champion Ed "Strangler" Lewis in St. Louis and was encouraged to challenge Lewis to a friendly contest. Although Thesz lost the 15-minute contest, Lewis was impressed by Thesz's skills and later became his manager and trainer.[16] Lewis later described Thesz as "lithe as a panther and exceptionally fast. He moves with the speed of a lightweight."[17] As his trainer, Lewis taught Thesz extremely painful and potentially crippling submission holds that would help him when facing opponents that refused to lose.[18]

Thesz made his professional wrestling debut at the age of 17, performing in undercard matches around the St. Louis territory whilst still working at his father's shoe repair shop. However, Thesz spent most of his early career honing his craft under the tutelage of George Tragos in both catch and freestyle wrestling, and later with Ad Santel.[19] When not taking a local booking, Tragos arranged Thesz with competitive workouts with top collegiate wrestlers in the region. Thesz then worked the Iowa, Nebraska, Minnesota and California territory, continuing to compete on the undercards while honing his craft on the road. Thesz notably worked out with top amateurs trained by Billy Thom, head coach of the 1936 U.S. Olympic wrestling team, and old carnival wrestlers around the region including Earl Wampler, who became his mentor and occasional workout partner on the road.[9][20]

By 1937, Thesz had become one of the biggest stars in the St. Louis territory, and on December 29 he defeated Everett Marshall for the American Wrestling Association World Heavyweight Championship in a grueling three hour match,[21][22] the first of many world heavyweight titles, which also made Thesz became the youngest world heavyweight champion in history, at the age of 21.[1] There is speculation that this match may have been a legitimate shoot contest.[23] Thesz later told wrestling historian Mike Chapman that he was there to wrestle competitively, which he did, and ended up winning the match, but was unsure if he actually won or Marshall dropped the title to him.[24] He later dropped the title to Steve "Crusher" Casey in Boston six weeks later. He won the National Wrestling Association World Heavyweight Championship in 1939, once again defeating Marshall, and again in 1948, defeating Bill Longson.

In 1948, the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) was formed, the purpose being to create one world champion for all the various wrestling territories throughout North America. Orville Brown, the reigning Midwest World Heavyweight Championship holder, was named the first champion. Thesz, at the time, was head of a promotional combine that included fellow wrestling champions Longson, Bobby Managoff, Canadian promoter Frank Tunney and Eddie Quinn, who promoted in the St. Louis territory where NWA promoter Sam Muchnick was running opposition. Quinn and Muchnick ended their promotional war, and Thesz' promotion was absorbed into the NWA. Part of the deal was a title unification match between Brown and Thesz, who held the National Wrestling Association's World Heavyweight Championship. Unfortunately, just weeks before the scheduled bout, Brown was involved in an automobile accident that ended his career, and he was forced to vacate the championship and the NWA awarded the title to the No. 1 contender, Thesz. Thesz was chosen for his skill as a "hooker" to prevent double crosses by would-be shooters who would deviate from the planned finish for personal glory.

Between 1949 and 1956, Thesz set out to unify all the existing world titles into the National Wrestling Alliance Worlds Heavyweight Championship. In 1952, he defeated Baron Michele Leone in Los Angeles for the California World Heavyweight title and became the closest any wrestler had been to being undisputed world heavyweight wrestling champion since Danno O'Mahony in 1936. Thesz finally dropped the title to Whipper Billy Watson in 1956, and took several months off to recuperate from an ankle injury. He regained the title from Watson seven months later.

1957 was an important year for Thesz; on June 14, the first taint to Thesz' claim of undisputed champion occurred in a match with gymnast-turned-wrestling star, Edouard Carpentier. The match was tied at two falls apiece when Thesz claimed a legitimate back injury and forfeit the last fall, thus Carpentier was declared the winner; however, the NWA chose not to recognize the title change, deciding a championship could not change hands due to injury. Despite the NWA's decision, there were some promotions who continued to recognize Carpentier's claim to the NWA World Heavyweight Championship. That same year, Thesz became the first wrestler to defend the NWA World Heavyweight Championship in Japan, wrestling Rikidōzan in a series of 60-minute draws. Their first match notably started as a legitimate contest as Rikidōzan believed himself to be a far superior wrestler. Thesz quickly dominated Rikidōzan and easily beat him to win the first fall. Rikidōzan accepted defeat and they worked the rest of the match. Their bouts popularized professional wrestling in Japan, gaining the sport mainstream acceptance. Realizing he could make more money in the land of the rising sun, Thesz petitioned to the NWA promoters to regularly defend the championship belt in Japan, but his request was turned down, and Thesz asked to drop the title to his own hand picked champion, Dick Hutton, rather than Thesz's real-life rival and the more popular choice, Buddy Rogers. Thesz would embark on a tour of Europe and Japan, billing himself as the NWA International Heavyweight Champion; this title is still recognized as a part of All Japan Pro Wrestling's Triple Crown Heavyweight Championship.

In 1963, Thesz came out of semi-retirement to win his sixth world heavyweight championship from Buddy Rogers at the age of 46. In 1964, he infamously faced Kintarō Ōki, a student of Rikidōzan, in what turned into a legitimate shoot contest. Originally scheduled for three falls, Ōki shot on Thesz in the first round. Ōki's move to shoot on Thesz ended things fast, as Thesz wounded him to the point that Ōki was stretchered off.[25] He would hold the NWA title until 1966 when, at the age of 50, he lost it to Gene Kiniski. On May 29, 1968, in Bombay, Dara Singh's victory over Lou Thesz earned Dara Singh the World Championship. According to Thesz, Singh (who was 12 years younger than Thesz) was "an authentic wrestler, and was superbly conditioned." For these reasons, Thesz had no problem losing to Dara Singh.[citation needed]

Thesz wrestled on a part-time basis over the next 13 years, winning his last major title in 1978, in Mexico, becoming the inaugural Universal Wrestling Alliance Heavyweight Champion at the age of 62, before dropping the championship to El Canek a year later. Thesz wrestled a match with Luke Graham in 1979 billed as his retirement match and considered himself retired after this, though he did continue to wrestle exhibition matches periodically through the 1980s. He finally wrestled his last public match on December 26, 1990, in Hamamatsu, Japan at the age of 74, against his protégé, Masahiro Chono.[1] This makes him one of the only male professional wrestlers, along with Abdullah The Butcher, to wrestle in seven different decades.[1]

After retiring, Thesz remained involved in the wrestling industry. He later became a special guest referee, promoter and trainer. He became the commissioner and occasional trainer for the shoot-style promotion Union of Professional Wrestling Forces International, and lent the promotion one of his old NWA championship belts, which they recognized as their own world title. With the promotion he spent one week every month in Japan teaching the wrestlers techniques in catch wrestling. However, by 1993 his enthusiasm for the UWFi waned as the company started moving away from its shootfighting style and favoring performers over wrestlers, and he soon severed relations with the company, taking his old championship belt back with him. His specific criticisms included the use of power bombs, deriding them as unrealistic despite his own use of them and their later use in MMA fights. As an announcer, Thesz was the color commentator for International World Class Championship Wrestling's weekly television show.

He was highly critical of modern-day professional wrestling and described it as 'choreographed tumbling', showcasing little to no actual wrestling skills. He commented on the rise of mixed martial arts and favourably compared it to his early days as a competitive catch wrestler.[26] Through his friendship with his student Gene LeBell, Thesz had an association with Gokor Chivichyan and LeBell's Hayastan MMA Academy.[27] He remained active as a wrestling coach, holding seminars in Virginia and later Florida. One of his most famous students, Kiyoshi Tamura, was one of the first men to beat a member of the Gracie family in over fifty years, beating Renzo Gracie by unanimous decision in an MMA fight.[28] Kit Bauman, co-writer of Thesz's autobiography Hooker, received a magazine mailed by Thesz that included a story on the sport of pankration, an Ancient Greek combat sport that blended wrestling and boxing (and considered an early precursor to MMA), with a brief note that Thesz wrote saying, "this sounds like something I would have enjoyed."[9] Thesz was frequently seen in attendance at NCAA wrestling events and was a lifelong supporter of amateur wrestling. He made occasional visits to top collegiate universities in the country, most notably striking up friendships with Old Dominion University head coach Gray Simons and University of Iowa head coach Dan Gable.[29][9]

In 1992, Thesz became the president of the Cauliflower Alley Club (CAC), an organization recognizing and supporting retired wrestlers, boxers and actors who enjoyed an association with wrestling. He served as CAC's president until 2000. In 1999, he helped establish the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame, a hall of fame and museum located within the National Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum's Dan Gable Museum. The hall of fame honors professional wrestlers with a strong amateur wrestling background. Thesz became the first inductee alongside George Tragos, Ed "Strangler" Lewis and Frank Gotch. He served on the Board of Directors and also did part-time coaching on the wrestling mats at the museum.[16]

Thesz was married three times. His first marriage to Evelyn Katherine Ernst on March 22, 1937.[9] Thesz was convalescing from a severe knee injury suffered in 1939 and from 1941 to 1944 worked as a dog breeder and trainer for Dogs for Defense and later as a supervisor for the Todd Houston Shipyard.[9] He divorced his first wife in 1944 and at the shipyard, Thesz met his second wife, Fredda Huddleston Winter, with whom he fathered three children: Jeff Thesz, Robert Thesz and Patrick Thesz.[9] Thesz's second marriage came to an end after he and Fredda divorced in 1975.[9] He married Charlie Catherine Thesz and remained with her for the rest of his life. Thesz lived in Norfolk, Virginia for much of his later life and started a wrestling school called the Virginia Wrestling Academy in 1988. One of Thesz's protégés Mark Fleming became head coach of the academy. He wrote an autobiography, Hooker: An Authentic Wrestler's Adventures Inside the Bizarre World of Professional Wrestling. Thesz was drafted into the army in 1944, despite a legitimate injury to his knee and multiple medical deferments. Owing to his wrestling background, he taught hand-to-hand combat defense for medics before being discharged in 1946.[9]

Thesz remained in good health through his older years, however after undergoing triple bypass surgery for an aortic valve replacement on April 9, 2002, he died due to complications weeks later on April 28, four days after his 86th birthday, in Orlando, Florida.[30][31][2][32]

Thesz is strongly considered by many to be the greatest professional wrestler of the 20th century.[33] Among his many accomplishments in the sport, he is credited with inventing a number of professional wrestling moves and holds such as the belly-to-back waistlock suplex (later known as the German suplex due to its association with Karl Gotch), the Lou Thesz press, stepover toehold facelock (STF), and the original powerbomb.

Thesz was the first wrestler to ever hold the NWA International Heavyweight Championship, which became a part of what is now the Triple Crown Heavyweight Championship under All Japan Pro Wrestling.[34][35] Thesz was also the first UWA World Heavyweight Champion for the now defunct Universal Wrestling Association in Mexico, where he won the title after defeating Mil Máscaras on July 26, 1976. Thesz was the first ever TWWA World Heavyweight Champion for the now defunct International Wrestling Enterprise as well.[36] Thesz and "The Outlaw" (Dory Funk Sr.) were the first ever NWA Pacific Coast (Vancouver) Tag Team Champions.[37]

In 1999, his name was given to the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame for professional wrestling stars with a successful amateur background at the International Wrestling Institute and Museum in Waterloo, Iowa, where he was an inaugural inductee. In October 1997, Thesz was honored by a ceremony at World Wrestling Federation's (WWF) Badd Blood as being both the youngest and oldest world heavyweight champion at ages 21 and 50, respectively[1] (technically, Verne Gagne holds the record for oldest champ, when he held the AWA World Heavyweight Championship in 1980 at age 54, which was tied by WWF owner Vince McMahon in 1999; Thesz has since been supplanted as the oldest NWA World Heavyweight Champion by former champion Tim Storm (who was born on February 18, 1964), who won the title at age 52 by defeating Jax Dane on October 21, 2016). In 1999, a large group of professional wrestling experts, analysts and historians named Thesz the most influential NWA World Heavyweight Champion of all time.[38] In 2002, Thesz was named the second greatest professional wrestler of all time behind Ric Flair in the magazine article "100 Wrestlers of All Time" by John Molinaro, edited by Dave Meltzer and Jeff Marek.[39]

Former NCAA champion and NWA World Heavyweight Champion Jack Brisco named Thesz his all-time favorite professional wrestler by saying that "Lou Thesz was my idol. He was a great wrestler, a great example, a class man".[40] AEW wrestler Claudio Castagnoli named Thesz his "dream" tag team partner and said, "He [Thesz] personifies wrestling. He represents everything that I think it should be. He's a class act, and he was a workhorse for the company, while at the same time being a student of the game. He was completely legit. I would have loved a chance to go one-on-one with him or to work alongside him".[41] Japanese wrestler Rikidōzan, who had several matches with Thesz in Japan, considered Thesz to be the greatest wrestler of all time and lamented that "after the match with the world's greatest wrestler, fights with other run-of-the-mill wrestlers became unappetizing for me".[42]

Three-time NCAA heavyweight champion and NWA World Heavyweight Champion Dick Hutton said that Thesz was the best man he ever met, in any type of wrestling (both competitive and performance).[3] Hutton later said that Thesz was "the only man I ever faced in the ring, professional or amateur, who was faster than I was."[43] National judo champion, grappler and professional wrestler Gene LeBell said that he considered Thesz to be one of his 'teachers', saying "Lou Thesz, Karl Gotch and Vic Christy all taught me a lot about grappling... From Thesz I learned how to hurt people. He had a little bit of a sadistic side". LeBell also mentioned that he learned most of his submission grappling from Thesz.[44] LeBell also considers Thesz, Ed "Strangler" Lewis and Karl Gotch as the toughest men he has ever known.[45] Wrestling promoter Sam Muchnick considered Ed "Strangler" Lewis as the greatest legitimate wrestler he had ever seen, with Thesz, Ray Steele, Joe Stecher, Jim Londos and John Pesek "only a few steps behind Lewis."[14] Fellow catch wrestler Billy Robinson considered Thesz to be the greatest professional wrestler of all time, saying "everybody respected professional wrestling because of Lou Thesz. He may not have been the best competitive catch wrestler but he was very good in his time."[46]

Thesz is an inaugural member of several professional wrestling halls of fame, including the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum, Wrestling Observer Newsletter Hall of Fame, NWA Hall of Fame, WCW Hall of Fame, and the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame which is subsequently named after both one of his trainers along with Thesz himself.[47] On April 2, 2016, Thesz was posthumously inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame as an inaugural member of the "Legacy" wing.

1 Thesz's first NWA World Heavyweight Championship reign began when he was awarded the championship by the NWA board of directors, rather than him winning the championship in a National Wrestling Alliance-affiliated promotion.[59] The National Wrestling Alliance regarded Thesz as a record-setting, six-time champion, recognizing his three additional reigns from the National Wrestling Association, and considered Harley Race to have broken this record when he won a seventh reign in 1983.[60]

2 The World Heavyweight Championship of the National Wrestling Association existed from 1929 through 1949, until it was unified with the world championship used by the National Wrestling Alliance.

3 While the title is best known as the NWA Texas Heavyweight Championship, Thesz's reigns with the title occurred prior to the NWA assuming control of it. In fact, he won the title before the NWA was created.

4 Thesz's two reigns with the title occurred prior to its unification with the NWA World Heavyweight Championship.