-

Hungarians in Romania (according to the 2021 census)

-

Hungarians in Vojvodina, Serbia (according to the 2002 census)

-

Hungarians in Slovakia (according to the 2011 census)

-

Hungarians in Ukraine (according to the 2001 census)

-

Hungarians in the United States (according to the 2018 census)

-

Hungarians of Croatia (according to the 2011 census)

-

Hungarians in Germany (according to the 2021 census)

| Person | Magyar |

|---|---|

| People | Magyarok |

| Language | Magyar nyelv, Magyar jelnyelv |

| Country | Magyarország |

Hungarians, also known as Magyars (/ˈmæɡjɑːrz/ MAG-yarz;[26] Hungarian: magyarok [ˈmɒɟɒrok]), are a Central European nation and an ethnic group native to Hungary (Hungarian: Magyarország) and historical Hungarian lands (i.e. belonging to the former Kingdom of Hungary) who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Uralic language family, alongside, most notably Finnish and Estonian.

There are an estimated 14.5 million ethnic Hungarians and their descendants worldwide, of whom 9.6 million live in today's Hungary.[1] About 2 million Hungarians live in areas that were part of the Kingdom of Hungary before the Treaty of Trianon in 1920 and are now parts of Hungary's seven neighbouring countries, Slovakia, Ukraine, Romania, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, and Austria. In addition, significant groups of people with Hungarian ancestry live in various other parts of the world, most of them in the United States, Canada, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Chile, Brazil, Australia, and Argentina, and therefore constitute the Hungarian diaspora (Hungarian: magyar diaszpóra).

Furthermore, Hungarians can be divided into several subgroups according to local linguistic and cultural characteristics; subgroups with distinct identities include the Székelys (in eastern Transylvania as well as a few in Suceava County, Bukovina), the Csángós (in Western Moldavia), the Palóc, and the Matyó.

Name

[edit]The Hungarians' own ethnonym to denote themselves in the Early Middle Ages is uncertain. The exonym "Hungarian" is thought to be derived from Oghur-Turkic On-Ogur (literally "Ten Arrows" or "Ten Tribes"). Another possible explanation comes from the Russian word "Yugra" (Югра). It may refer to the Hungarians during a time when they dwelt east of the southern Ural Mountains in Western Siberia before their conquest of the Carpathian Basin.[27]

Prior to the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin when the Hungarian conquerors lived on the steppes of Eastern Europe east of the Carpathian Mountains, written sources called the Hungarians: "Ungri" by Georgius Monachus in 837, "Ungri" by Annales Bertiniani in 862, and "Ungari" by the Annales ex Annalibus Iuvavensibus in 881. The Magyars/Hungarians probably belonged to the Onogur tribal alliance, and it is possible that they became its ethnic majority.[28] In the Early Middle Ages, the Hungarians had many names, including "Węgrzy" (Polish), "Ungherese" (Italian), "Ungar" (German), and "Hungarus".[29]

In the Hungarian language, the Hungarian people name themselves as "Magyar".[28] "Magyar" possibly derived from the name of the most prominent Hungarian tribe, the "Megyer". The tribal name "Megyer" became "Magyar" in reference to the Hungarian people as a whole.[30][31][32]

The Greek cognate of "Tourkia" (Greek: Τουρκία) was used by the scholar and Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in his De Administrando Imperio of c. AD 950,[33][34] though in his use, "Turks" always referred to Magyars.[35] This was a misnomer, as while the Magyars do have some Turkic genetic and cultural influence, including their historical social structure being of Turkic origin,[36] they still are not widely considered as part of the Turkic people.[37]

The obscure name kerel or keral, found in the 13th-century work The Secret History of the Mongols, possibly referred to Hungarians and derived from the Hungarian title király 'king'.[38]

The historical Latin phrase "Natio Hungarica" ("Hungarian nation") had a wider and political meaning because it once referred to all nobles of the Kingdom of Hungary, regardless of their ethnicity or mother tongue.[39]

History

[edit]Origin

[edit]The origin of Hungarians, the place and time of their ethnogenesis, has been a matter of debate. The Hungarian language is classified in the Ugric family, the range of the original Ugric people is predicted to have been east of the Ural Mountains, south of the forest zone and not far from the steppe.[40] The relatedness of Hungarians with other Ugric peoples is confirmed by linguistic and genetic data, but modern Hungarians have also substantial admixture from local European populations.[41] The Ugric languages are a member of the Uralic family, which originated either in the Oka-Volga region, the Southern Uralic, or Western Siberia. Recent linguistic data support an origin somewhere in Western Siberia. Ugric diverged from its relatives in the first half of the 1st millennium BC, in western Siberia, east of the southern Urals. The ancient Ugrians are associated with the Mezhovskaya culture, and were influenced by the Iranian Sarmatians and Saka, as well as later Xiongnu. The Ugrians also display genetic affinities to the Pazyryk culture. They arrived into Central Europe by the historical Magyar or Hungarian "conquerors", in the Hungarian landtaking.[40][42]

The historical Magyar conquerors were found to show significant affinity to modern Bashkirs, and stood also in contact with other Turkic peoples (presumably Oghuric speakers), Iranian peoples (especially Jaszic speakers), and Slavs. The historical Magyars created an alliance of steppe tribes, consisting of an Ugric/Magyar ruling class, and formerly Iranian but also Turkic (Oghuric) and Slavic speaking tribes, which conquered the Pannonian Steppe and surrounding regions, giving rise to modern Hungarians and Hungarian culture.[43]

"Hungarian pre-history", i.e. the history of the "ancient Hungarians" before their arrival in the Carpathian basin at the end of the 9th century, is thus a "tenuous construct", based on linguistics, analogies in folklore, archaeology and subsequent written evidence. In the 21st century, historians have argued that "Hungarians" did not exist as a discrete ethnic group or people for centuries before their settlement in the Carpathian basin. Instead, the formation of the people with its distinct identity was a process. According to this view, Hungarians as a people emerged by the 9th century, subsequently incorporating other, ethnically and linguistically divergent, peoples.[44]

Pre-4th century AD

[edit]

During the 4th millennium BC, the Uralic-speaking peoples who were living in the central and southern regions of the Urals split up. Some dispersed towards the west and northwest and came into contact with Turkic and Iranian speakers who were spreading northwards.[45] From at least 2000 BC onwards, the Ugric-speakers became distinguished from the rest of the Uralic community, of which the ancestors of the Magyars, being located farther south, were the most numerous. Judging by evidence from burial mounds and settlement sites, they interacted with the Indo-Iranian Andronovo culture and Baikal-Altai Asian cultures.[46][43]

4th century to c. 830

[edit]In the 4th and 5th centuries AD, the Hungarians were an "[e]thnically mixed people"[47] who moved to the west of the Ural Mountains, to the area between the southern Ural Mountains and the Volga River, known as Bashkiria (Bashkortostan) and Perm Krai. In the early 8th century, some of the Hungarians moved to the Don River, to an area between the Volga, Don and the Seversky Donets rivers.[48] Meanwhile, the descendants of those Hungarians who stayed in Bashkiria remained there as late as 1241.

The Hungarians around the Don River were subordinates of the Khazar Khaganate. Their neighbours were the archaeological Saltov culture, i.e. Bulgars (Proto-Bulgarians, Onogurs) and the Alans, from whom they learned gardening, elements of cattle breeding and of agriculture. Tradition holds that the Hungarians were organized in a confederacy of seven tribes: Jenő, Kér, Keszi, Kürt-Gyarmat, Megyer, Nyék, and Tarján.

c. 830 to c. 895

[edit]Around 830, a rebellion broke out in the Khazar khaganate. As a result, three Kabar tribes[49] of the Khazars joined the Hungarians and moved to what the Hungarians call the Etelköz, the territory between the Carpathians and the Dnieper River. The Hungarians faced their first attack by the Pechenegs around 854.[48] The new neighbours of the Hungarians were the Varangians and the eastern Slavs. From 862 onwards, the Hungarians (already referred to as the Ungri) along with their allies, the Kabars, started a series of looting raids from the Etelköz into the Carpathian Basin, mostly against the Eastern Frankish Empire (Germany) and Great Moravia, but also against the Balaton principality and Bulgaria.[50]

Entering the Carpathian Basin (c. 862–895)

[edit]

The Hungarians arrived in the Carpathian Basin, a geographically unified but politically divided land, after acquiring thorough local knowledge of the area from the 860s onwards.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57]

After the end of the Avar Kaganate (c. 822), the Eastern Franks asserted their influence in Transdanubia, the Bulgarians to a small extent in the Southern Transylvania and the interior regions housed the surviving Avar population in their stateless state.[52][58] The downfall of the Avar Khaganate at the beginning of the 9th century did not mean the extinction of the Avar population, contemporary written sources report surviving Avar groups.[53] According to the archaeological evidence, the Avar population survived the time of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin.[52][56][59] In this power vacuum, the Hungarian conqueror elite took the system of the former Avar Kaganate, there is no trace of massacres and mass graves, it is believed to have been a peaceful transition for local residents in the Carpathian Basin.[59] The Hungarian conquerors together with the Turkic-speaking Kabars integrated the Avars and Onogurs.[60]

In 862, Prince Rastislav of Moravia rebelled against the Franks, and after hiring Hungarian troops, won his independence; this was the first time that Hungarians expeditionary troops entered the Carpathian Basin.[61][62] In 862, Archbishop Hincmar of Reims records the campaign of unknown enemies called "Ungri", giving the first mention of the Hungarians in Western Europe. In 881, the Hungarian forces fought together with the Kabars in the Vienna Basin.[61][63] According to historian György Szabados and archeologist Miklós Béla Szőke, a group of Hungarians were already living in the Carpathian Basin at that time, so they could quickly intervene in the events of the Carolingian Empire.[51][52][53][58][63] The number of recorded battles increased from the end of the 9th century.[58] In the late Avar period, a part of Hungarians was already present in the Carpathian Basin in the 9th century, this has been supported by genetic and archaeological research, because there are graves in which Avar descendants are buried in Hungarian clothes.[64][63] The contemporary local population is descended from previous peoples of the Carpathian Basin, and a large number of people survived to the 10th century from the previous Avar period.[65] An important segment of this Avar era Hungarians is that the Hungarian county system of King Saint Stephen I may be largely based on the power centers formed during the Avar period.[64] Based on DNA evidence, the Proto-Hungarians admixed with Sarmatians and Huns, this three genetic components appear in the graves of the Hungarian conqueror elite of the 9th century.[66] Based on the DNA in the Hungarian conqueror graves, the conquerors had eastern origin, but the vast majority of the Hungarian conquerors had European genome.[67][59] The remains in cemeteries of the Hungarian commoners had fewer Eastern Asian ancestry than the remains in cemeteries of the Hungarian elite, which displasey around 1/3 Eastern ancestry. Commoners clustered with surrounding non-Hungarian groups, while elite remains clustered with modern day Volga Tatars and Bashkirs, who are regarded as turkified formerly Uralic/Ugric-speaking ethnicities.[66][65][59][68] According to some genetic studies, there is a genetic continuity from the Bronze Age, a continuous migration of the Steppe folks from east to the Carpathian Basin.[59][69] Other studies point out that the Hungarian conqueror group and the local population started admixing only on the second half of the 10th century, and that research done of the first and second generation cemeteries in the Carpathian basin show uniparental lineages can be derived from Iron Age Sargat culture's population, suggesting "only limited interaction with the local population of the Carpathian Basin".[70]

The foundation of the Hungarian state is connected to the Hungarian conquerors, who arrived from the Pontic steppes as a confederation of seven tribes. The Hungarians arrived in the frame of a strong centralized steppe-empire under the leadership of Grand Prince Álmos and his son Árpád, they became founders of the Árpád dynasty, the Hungarian ruling dynasty and the Hungarian state. The Árpád dynasty claimed to be a direct descendant of the great Hun leader Attila.[71][72][73] Medieval Hungarian chronicles from the Hungarian royal court like the Gesta Hungarorum, Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum, Chronicon Pictum, Buda Chronicle, Chronica Hungarorum claimed that the Árpád dynasty and the Aba clan are the descendants of Attila.[71]

Árpád, Grand Prince of the Hungarians, says in the Gesta Hungarorum:

The land stretching between the Danube and the Tisza used to belong to my forefather, the mighty Attila.

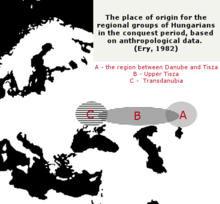

The Hungarians took possession of the Carpathian Basin in a pre-planned manner, with a long move-in between 862 and 895.[51][52][54][55][56][58][63][75] This is confirmed by the archaeological findings, in the 10th-century Hungarian cemeteries, the graves of women, children and elderly people are located next to the warriors, they were buried according to the same traditions, wore the same style of ornaments, and belonged to the same anthropological group. The Hungarian military events of the following years prove that the Hungarian population that settled in the Carpathian Basin was not a weakened population without a significant military power.[56] Other theories assert that the move of the Hungarians was forced or at least hastened by the joint attacks of Pechenegs and Bulgarians.[56][76] According to eleventh-century tradition, the road taken by the Hungarians under Prince Álmos took them first to Transylvania in 895. This is supported by an eleventh-century Russian tradition that the Hungarians moved to the Carpathian Basin by way of Kiev.[77] Prince Álmos, the sacred leader of the Hungarian Great Principality died before he could reach Pannonia, he was sacrificed in Transylvania.[61][78]

In 895/896, under the leadership of Árpád, some Hungarians crossed the Carpathians and entered the Carpathian Basin. The tribe called Megyer was the leading tribe of the Hungarian alliance that conquered the centre of the basin. At the same time (c. 895), due to their involvement in the 894–896 Bulgaro-Byzantine war, Hungarians in Etelköz were attacked by Bulgaria and then by their old enemies the Pechenegs. The Bulgarians won the decisive battle of Southern Buh. It is uncertain whether or not those conflicts contributed to the Hungarian departure from Etelköz.

From the upper Tisza region of the Carpathian Basin, the Hungarians intensified their campaigns across continental Europe. In 900, they moved from the upper Tisza river to Transdanubia, which later became the core of the arising Hungarian state. By 902, the borders were pushed to the South-Moravian Carpathians and the Principality of Moravia collapsed.[79] At the time of the Hungarian migration, the land was inhabited only by a sparse population of Slavs, numbering about 200,000,[48] who were either assimilated or enslaved by the Hungarians.[48]

Archaeological findings (e.g. in the Polish city of Przemyśl) suggest that many Hungarians remained to the north of the Carpathians after 895/896.[80] There is also a consistent Hungarian population in Transylvania, the Székelys, who comprise 40% of the Hungarians in Romania.[81][82] The Székely people's origin, and in particular the time of their settlement in Transylvania, is a matter of historical controversy.

After 900

[edit]

In 907, the Hungarians destroyed a Bavarian army in the Battle of Pressburg and laid the territories of present-day Germany, France, and Italy open to Hungarian raids, which were fast and devastating. The Hungarians defeated the Imperial Army of Louis the Child, son of Arnulf of Carinthia and last legitimate descendant of the German branch of the house of Charlemagne, near Augsburg in 910. From 917 to 925, Hungarians raided through Basel, Alsace, Burgundy, Saxony, and Provence.[83] Hungarian expansion was checked at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955, ending their raids against Western Europe, but raids on the Balkan Peninsula continued until 970.[84]

The Pope approved Hungarian settlement in the area when their leaders converted to Christianity, and Stephen I (Szent István, or Saint Stephen) was crowned King of Hungary in 1001. The century between the arrival of the Hungarians from the eastern European plains and the consolidation of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1001 was dominated by pillaging campaigns across Europe, from Dania (Denmark) to the Iberian Peninsula (contemporary Spain and Portugal).[citation needed] After the acceptance of the nation into Christian Europe under Stephen I, Hungary served as a bulwark against further invasions from the east and south, especially by the Turks.

At this time, the Hungarian nation numbered around 400,000 people.[48]

Early modern period

[edit]The first accurate measurements of the population of the Kingdom of Hungary including ethnic composition were carried out in 1850–51. There is a debate among Hungarian and non-Hungarian (especially Slovak and Romanian) historians about the possible changes in the ethnic structure of the region throughout history. The proportion of Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin was at an almost constant 80% during the Middle Ages.[85] The Hungarian population began to decrease only at the time of the Ottoman conquest, reaching as low as around 39% by the end of the 18th century.[86][87]

The decline of the Hungarians was due to the constant wars, Ottoman raids, famines, and plagues during the 150 years of Ottoman rule. The main zones of war were the territories inhabited by the Hungarians, so the death toll depleted them at a much higher rate than among other nationalities.[86][87] In the 18th century, their proportion declined further because of the influx of new settlers from Europe, especially Slovaks, Serbs and Germans.[88] In 1715 (after the Ottoman occupation), the Southern Great Plain was nearly uninhabited but now has 1.3 million inhabitants, nearly all of them Hungarians. As a consequence, having also the Habsburg colonization policies, the country underwent a great change in ethnic composition as its population more than tripled to 8 million between 1720 and 1787, while only 39% of its people were Hungarians, who lived primarily in the centre of the country.[89]

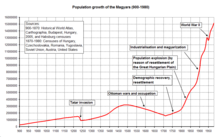

19th century to present

[edit]In the 19th century, the proportion of Hungarians in the Kingdom of Hungary rose gradually, reaching over 50% by 1900 due to higher natural growth and Magyarization. Between 1787 and 1910 the number of ethnic Hungarians rose from 2.3 million to 10.2 million, accompanied by the resettlement of the Great Hungarian Plain and Délvidék by mainly Roman Catholic Hungarian settlers from the northern and western counties of the Kingdom of Hungary. Spontaneous assimilation was an important factor, especially among the German and Jewish minorities and the citizens of the bigger towns. On the other hand, about 1.5 million people (about two-thirds non-Hungarian) left the Kingdom of Hungary between 1890–1910 to escape from poverty.[90]

The years 1918 to 1920 were a turning point in the Hungarians' history. By the Treaty of Trianon, the Kingdom had been cut into several parts, leaving only a quarter of its original size. One-third of the Hungarians became minorities in the neighbouring countries.[91] During the remainder of the 20th century, the Hungarians population of Hungary grew from 7.1 million (1920) to around 10.4 million (1980), despite losses during the Second World War and the wave of emigration after the attempted revolution in 1956.

The number of Hungarians in the neighbouring countries tended to remain the same or slightly decreased, mostly due to assimilation (sometimes forced; see Slovakization and Romanianization)[92][93][94] and to emigration to Hungary (in the 1990s, especially from Transylvania and Vojvodina). After the "baby boom" of the 1950s (Ratkó era), a serious demographic crisis began to develop in Hungary and its neighbours.[95] The Hungarian population reached its maximum in 1980, then began to decline.[95]

For historical reasons (see Treaty of Trianon), significant Hungarian minority populations can be found in the surrounding countries, most of them in Romania (in Transylvania), Slovakia, and Serbia (in Vojvodina). Sizable minorities live also in Ukraine (in Transcarpathia), Croatia (primarily Slavonia), and Austria (in Burgenland). Slovenia is also host to a number of ethnic Hungarians, and Hungarian language has an official status in parts of the Prekmurje region. Today more than two million ethnic Hungarians live in nearby countries.[96]

There was a referendum in Hungary in December 2004 on whether to grant Hungarian citizenship to Hungarians living outside Hungary's borders (i.e. without requiring a permanent residence in Hungary). The referendum failed due to insufficient voter turnout. On 26 May 2010, Hungary's Parliament passed a bill granting dual citizenship to ethnic Hungarians living outside of Hungary. Some neighboring countries with sizable Hungarian minorities expressed concerns over the legislation.[97]

Ethnic affiliations and genetic origins

[edit]

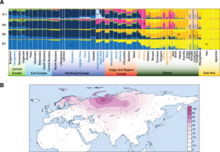

Modern Hungarians stand out as linguistically isolated in Europe, despite their genetic similarity to the surrounding populations. The population of the Carpathian Basin has the common European gene-pool which formed in the Bronze Age through the admixture of three sources: Western Hunter-Gatherers, who were the first Homo sapiens appearing in Paleolithic Europe, Neolithic farmers originating from Anatolia, and Yamnaya steppe migrants that arrived in the late Neolithic to early Bronze Age. This common European gene pool in the Carpathian Basin, has been overlaid by migration waves originating from the east since the Iron Age.[40] According to genetic studies, the Carpathian Basin was continuously inhabited from at least the Bronze Age.[98][40] There is a genetic continuity from the Bronze Age, a continuous migration of the Steppe folks from east to the Carpathian Basin.[99][40] The foundational population of the Carpathian Basin carrying the common European gene pool remained in a significant majority throughout the migratory periods in the Carpathian Basin.[40] During the 9th century BC, smaller groups of pre-Scythians (Cimmerians) of the Mezőcsát culture appeared. The classic Scythian culture spread across the Great Hungarian Plain between the 7th–6th century BC, their genetic data represent the genetic profile of the local European population. The Sarmatians arrived in multiple waves from 50 BC, leaving a significant archaeological heritage behind, the examined Sarmatian individuals genetically also belong to the genetic legacy of the local European population. Various groups of Asian origin settled in the Carpathian Basin, such as Huns, Avars, Hungarian conquerors, Pechenegs, Jazyg people, and Cumans. The military leadership of the European Huns descended from the Asian Huns (Xiongnus), while the majority of them consisted of subjugated Germanic and Sarmatian populations. The most significant influx of genes from Asia occurred during the Avar period, arriving in multiple waves. The ruling elite of the Avars originated from the Rouran Khaganate in Mongolia, but a significant portion of the masses they brought in consisted of mixed-origin populations that had emerged in the Pontic-Caspian steppe during the Hunnic era.[40] Foundation of the Hungarian state is connected to the Hungarian conquerors, who arrived from the Pontic steppes as a confederation of seven tribes.[72][73] According to genetic study, the proto-Ugric groups were part of the Scytho-Siberian societies in the late Bronze Age to early Iron Age steppe-forest zone in the northern Kazakhstan region, near of the Mezhovskaya culture territory. The ancestors of the Hungarian conquerors lived in the steppe zone during the Bronze Age together with the Mansis. During the Iron Age, the Mansis migrated northward, while the ancestor of Hungarian conquerors remained at the steppe-forest zone and admixed with the Sarmatians. Later the ancestors of the Hungarian conquerors admixed with the Huns, this admixture happened before the arrival of the Huns to the Volga region in 370. The Huns integrated local tribes east of the Urals, among them Sarmatians and the ancestors of the Hungarian conquerors.[66][40] The Hungarians arrived in the frame of a strong centralized steppe-empire under the leadership of Grand Prince Álmos and his son Árpád, they became founders of the Árpád dynasty, the Hungarian ruling dynasty and the Hungarian state. The Árpád dynasty claimed to be a direct descendant of the great Hun leader Attila.[100][72][73] The elite of the conquering Hungarians established the Hungarian state, genetic studies revealed, the conqueror elite in both sexes has approximately 30% Eastern Eurasian components, while the commoner population appears to have carried the overlaid local European gene pool from previous eastern immigrations.[40] In medieval Hungary, a legend developed based on foreign and Hungarian medieval chronicles that the Hungarians, and the Székely ethnic group in particular, are descended from the Huns. The basic premise of the Hungarian medieval chronicle tradition was that the Huns, i.e. the Hungarians coming out twice from Scythia, the guiding principle was the Hun-Hungarian continuity.[101] The 20th century mainstream scholarship dismisses a close connection between the Hungarians and Huns.[102] However, the archaeogenetics studies revealed the Hun heritage of the Hungarian conquerors, it was a significant Hun-Hungarian mixing around 300 AD, and the remaining Huns were integrated into the conquering Hungarians.[66][103][104][69] The genomic analyses of the Hungarian royal Árpád family members are in line with the reported conquering Hungarian-Hun origin of the dynasty in harmony with their Y-chromosomal phylogenetic connections.[105] According to the growing archaeological evidence that the Avar population lived through the period of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin. The Carpathian Basin was demonstrably not empty when the Hungarian conquerors led by Árpád arrived. The conquering Hungarians mixed to varying degrees on individual level with the Avar population living in the Carpathian Basin, but they had Avar genetic heritage as well.[98] According to Endre Neparáczki, it is no longer possible to narrow down the Hungarian population of the Carpathian Basin only of people of Árpád.[98] Following the devastations caused by the Mongol and Turkish invasions, settlers from other parts of Europe played a significant role in establishing the modern genetic makeup of the Carpathian Basin.[40]

The Hungarian language belongs to the Uralic language family. While early Ugric-speakers can be associated with an ancestry component maximized in modern-day Khanty/Mansi and historical Southern Siberian groups such as the Pazyryk culture people, the earliest Uralic-speakers can be associated with an Ancient Northern East Asian lineage maximized among modern Nganasans and a Bronze Age specimen from Krasnoyarsk in southern Siberia (Krasnoyarsk_Krai_BA; kra001).[42][40][106][107][108] This type of ancestry later dispersed along the Seima-Turbino route westwards. They may also stood in contact with other Ancient Northeast Asians (partially linked to the ethnogenesis of Turkic and Mongolic peoples[109][110][111]) and Western Steppe Herders (Indo-European). Modern Hungarians are however genetically rather distant from their closest linguistic relatives (Mansi and Khanty), and more similar to the neighbouring non-Uralic neighbors. Modern Hungarians share a small but significant "Inner Asian/Siberian" component with other Uralic-speaking populations.[112] The historical Hungarian conqueror YDNA variation had a higher affinity with modern day Bashkirs and Volga Tatars as well as to two specimens of the Pazyryk culture, while their mtDNA has strong links to the populations of the Baraba region, Inner Asia, Eastern Europe, Northern Europe and Central Asia. Modern Hungarians also display genetic affinity with historical Sintashta samples.[43][42]

Archeological mtDNA haplogroups show a similarity between Hungarians and Turkic-speaking Tatars and Bashkirs, while another study found a link between the Mansi and Bashkirs, suggesting that the Bashkirs are a mixture of Turkic, Ugric and Indo-European contributions. The homeland of ancient Hungarians is around the Ural Mountains, and the Hungarian affinities with the Karayakupovo culture is widely accepted among researchers.[113][114] A full genome study found that the Bashkirs display, next to their high European ancestry, also affinity to both Uralic-speaking populations of Northern Asia, as well as Inner Asian Turkic groups, "pointing to a mismatch of their cultural background and genetic ancestry and an intricacy of the historic interface between Turkic and Uralic populations".[115]

The homeland of the proto-Uralic peoples may have been close to Southern Siberia, among forest cultures in the Altai-Sayan region and may be linked to an ancestry maximized in the early Tarim mummies. The arrival of the Indo-European Afanasievo culture and Northeast Asian tribes may have caused the dispersal and expansion of proto-Uralic languages along the Seima-Turbino cultural area.[116]

Neparáczki et al. argues, based on archeogenetic results, that the historical Hungarian Conquerors were mostly a mixture of Central Asian Steppe groups, Slavic, and Germanic tribes, and this composite people evolved between 400 and 1000 AD.[117][118] According to Neparáczki: "From all recent and archaic populations tested the Volga Tatars show the smallest genetic distance to the entire Conqueror population" and "a direct genetic relation of the Conquerors to Onogur-Bulgar ancestors of these groups is very feasible."[119] Genetic data found high affinity between Magyar conquerors, the historical Bulgars, and modern day Turkic-speaking peoples in the Volga region, suggesting a possible language shifted from an Uralic (Ugric) to Turkic languages.[120]

Hunnish origin or influences on Hungarians and Székelys have always been a matter of debate among scholars. In Hungary, a legend developed based on medieval chronicles that the Hungarians, and the Székely ethnic group in particular, are descended from the Huns. However, mainstream scholarship dismisses a close connection between the Hungarians and Huns.[121][122][123] A genetic study published in Scientific Reports in November 2019 led by Neparáczki Endre had examined the remains of three males from three separate 5th century Hunnic cemeteries in the Pannonian Basin. They were found to be carrying the paternal haplogroups Q1a2, R1b1a1b1a1a1 and R1a1a1b2a2. In modern Europe, Q1a2 is rare and has its highest frequency among the Székelys. It is believed that conquering Magyars may have absorbed Avar, Hunnish and Xiongnu influences.[124]

Paternal haplogroups

[edit]Hungarian males possess a high frequency of haplogroup R1a-Z280 and a low frequency of haplogroup N-Tat, which is uncommon among most Uralic-speaking populations.

In the case of the Southern Mansi males, the most frequent haplogroups were N1b-P43 (33%), N1c-L1034 (28%) and R1a-Z280 (19%).The Konda Mansi population shared common haplotypes within haplogroups R1a-Z280 or N-M46 with Hungarian speakers, which may suggest that the Hungarians were in contact with the Mansi people during their migration to the Carpathian Basin.[125]

According to a study by Pamjav, the area of Bodrogköz suggested to be a population isolate found an elevated frequency of Haplogroup N: R1a-M458 (20.4%), I2a1-P37 (19%), R1a-Z280 (14.3%), and E1b-M78 (10.2%). Various R1b-M343 subgroups accounted for 15% of the Bodrogköz population. Haplogroup N1c-Tat covered 6.2% of the lineages, but most of it belonged to the N1c-VL29 subgroup, which is more frequent among Balto-Slavic speaking than Finno-Ugric speaking peoples. Other haplogroups had frequencies of less than 5%.[126]

Among 100 Hungarian men, 90 of whom from the Great Hungarian Plain, (including Cuman descendants from Kunság region) the following haplogroups and frequencies are obtained: 30% R1a, 15% R1b, 13% I2a1, 13% J2, 9% E1b1b1a, 8% I1, 3% G2, 3% J1, 3% I*, 1% E*, 1% F*, 1% K*. The 97 Székelys belong to the following haplogroups: 20% R1b, 19% R1a, 17% I1, 11% J2, 10% J1, 8% E1b1b1a, 5% I2a1, 5% G2, 3% P*, 1% E*, 1% N.[127] It can be inferred that Szekelys have more significant German admixture. A study sampling 45 Palóc from Budapest and northern Hungary, found 60% R1a, 13% R1b, 11% I, 9% E, 2% G, 2% J2.[128] A study estimating possible Inner Asian admixture among nearly 500 Hungarians based on paternal lineages only, estimated it at 5.1% in Hungary, at 7.4 in Székelys and at 6.3% at Csángós.[129]

An analysis of Bashkir samples from the Burzyansky and Abzelilovsky districts of the Republic of Bashkortostan in the Volga-Ural region, revealed them to belong to the R1a subclade R1a-SUR51, which is shared in significant amounts with the historical Magyars and the royal Hungarian lineage, and representing the closest kin to the Hungarian Árpád dynasty, whose ancestry is traced to 4500 years ago, in modern day Northern Afghanistan.[130][131] In turn, R1a-SUR51's ancestral subclades R1a-Y2632 are found among the Saka population of the Tien Shan, date: 427-422 BC.[132]

Historical Magyar conquerors had around ~37.5% Haplogroup N-M231, as well as lower frequency of Haplogroup C-M217 at 6.25% with the remainder being Haplogroup R1a and Haplogroup Q-M242.[43]

Autosomal DNA

[edit]Modern Hungarians show relative close affinity to surrounding populations, but harbour a small "Siberian" component associated with Khanty/Mansi, as well as the Nganasan people, and argued to have arrived with the historical Magyars. Modern Hungarians formed from several historical population groupings, including the historical Magyars, assimilated Slavic and Germanic groups, as well as Central Asian Steppe tribes (presumably Turkic and Iranian tribes).[43][133][115][134][40][107]

The historical Magyar genome corresponds largely with the modern Bashkirs, and can be modeled as ~50% Khanty/Mansi-like, ~35% Sarmatian-like, and ~15% Hun/Xiongnu-like. The admixture event is suggested to have taken place in the Southern Ural region at 643–431 BCE. Modern Hungarians were found to be admixed descendants of the historical Magyar conquerors with local Europeans, as 31 Hungarian samples could be modelled as two-way admixtures of "Conq_Asia_Core" and "EU_Core" in varying degrees. The historical Magyar component among modern Hungarians is estimated at an average frequency of 13%, which can be explained by the relative smaller population size of Magyar conquerors compared to local European groups.[43][133]

Other influences

[edit]| Word roots in Hungarian[135] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertain | 30% | |||

| Uralic | 21% | |||

| Slavic | 20% | |||

| Germanic | 11% | |||

| Turkic | 9.5% | |||

| Latin and Greek | 6% | |||

| Romance | 2.5% | |||

| Other known | 1% | |||

Besides the various peoples mentioned above, the Magyars were later influenced by other populations in the Carpathian Basin. Among these are the Cumans, Pechenegs, Jazones, West Slavs, Germans (more specifically Hungarian Germans but also Transylvanian Saxons or other ethnic German minorities in the former Kingdom of Hungary or in Central and Eastern Europe such as the Zipser Germans, and Vlachs (Romanians).

Ottomans, who occupied the central part of Hungary from c. 1526 until c. 1699, inevitably exerted an influence, as did the various nations (Germans/Banat Swabians, Slovaks, Serbs, Croats, and others) that resettled the depopulated central and southern territories of the kingdom (roughly present-day South Hungary, Vojvodina in Serbia and Banat in Romania) after their departure. Similar to other European countries, Armenian, and Roma (Gypsy) ethnic minorities have been living in Hungary since the Middle Ages. Jews have been living in Hungary since the Roman era, as the archeological evidence of Jewish gravestones dating from this period demonstrates.

Diaspora

[edit]

Hungarian diaspora (Magyar diaspora) is a term that encompasses the total ethnic Hungarian population located outside of current-day Hungary.

Maps

[edit]-

Kniezsa's (1938) view on the ethnic map of the Kingdom of Hungary in the 11th century, based on toponyms. Kniezsa's view has been criticized by many scholars, because of its non-compliance with later archaeological and onomastics research, but his map is still regularly cited in modern reliable sources. One of the most prominent critics of this map was Emil Petrovici.[136]

-

Ethnic map of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1495 by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Hungarians are depicted in orange)

-

The "Red Map",[137] based on the 1910 census. Regions with population density below 20 persons/km2 (52 persons/sq mi)[138] are left blank and the corresponding population is represented in the nearest region with population density above that limit. Red colour to mark Hungarians and light purple colour to mark Romanians.

-

Map of the Kingdom of Hungary in 1910, based on the Hungarian census of the same year. Hungarians are marked in dark green.

-

Ethnic map depicting the contemporary ethnic distribution of Hungarians across the Pannonian Basin (also known and referred to as the Carpathian Basin). Legend:Hungary proper where Hungarians are the ethnic majority peopleRegions outside Hungary where there are notable ethnic Hungarian minorities

Culture

[edit]The culture of Hungary shows distinctive elements, incorporating local European elements and minor Central Asian/Steppe derived traditions, such as Horse culture and Shamanistic remnants in Hungarian folklore.

Traditional costumes (18th and 19th century)

[edit]Folklore and communities

[edit]-

Hungarians dressed in folk costumes in Southern Transdanubia, Hungary

-

Vojvodina Hungarians women's national costume

-

The Hungarian Puszta

-

The Turul, the mythical bird of Hungary

-

Welcome sign in Latin and in Old Hungarian script for the town of Vonyarcvashegy, Hungary

See also

[edit]- Central Europe

- Demographics of Hungary

- List of Hungarians

- List of people of Hungarian origin

- Ugric languages

- Khanty people

- Mansi people

- Eastern Magyars

- Magyarab people

- Jász people

- Székelys of Bukovina

- Kunság

- Pole, Hungarian, two good friends

- Hungarian mythology

- Hunor and Magor

- Shamanistic remnants in Hungarian folklore

- List of domesticated animals from Hungary

- Hungarian Americans

- Hungarian cuisine

- Hungarian culture

- Romani people in Hungary

References

[edit]- ^ a b Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 – 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus – 12. Ethnic data] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Hungarian Central Statistical Office. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Széchely, István (3 January 2023). "Mintha városok ürültek volna ki" [As if cities had been emptied]. Székelyhon (in Hungarian). Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Holka Chudzikova, Alena (29 March 2022). "Data from census have confirmed that an exclusive national identity is a myth. This should also translate into the laws concerning national minorities". Minority policy in Slovakia. ISSN 2729-8663. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten nach Migrationshintergrund im weiteren Sinn nach ausgewählten Geburtsstaaten". Statistisches Bundesamt.

- ^ Srbija, Euronews (28 April 2023). "Konačni rezultati popisa prema nacionalnoj pripadnosti: Mađari najbrojnija manjina, Jugoslovena više od 27.000" (in Serbian). Euronews.rs. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "Hungarians in France". Archived from the original on 4 February 2007.

- ^ "Hungarians of France". PeopleGroups.org.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "It has been officially recognized: far more Hungarians live in the United Kingdom than previously thought". portfolio.hu. 16 February 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "About number and composition population of UKRAINE by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 2003. Archived from the original on 31 October 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination". migrationpolicy.org. 10 February 2014.

- ^ Befolkning efter födelseland och ursprungsland 31 December 2018

- ^ "Bevolking; geslacht, leeftijd, generatie en migratieachtergrond, 1 januari". CBS StatLine. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "A diaszpóra tudományos megközelítése". Kőrösi Csoma Sándor program. 3 July 2015.

- ^ "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples – Croatia : Overview (2001 census data)". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. July 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ "PeopleGroups.org – Hungarians of Slovenia". peoplegroups.org.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Magyar diaszpórapolitikastratégiai irányok" (PDF). kulhonimagyarok.hu (in Hungarian). 22 November 2016. p. 29.

- ^ Project, Joshua. "Hungarian in Bosnia-Herzegovina". joshuaproject.net.

- ^ Ludność. Stan i struktura demograficzno-społeczna. Narodowy Spis Ludności i Mieszkań 2011 (National Census of Population and Housing 2011). GUS. 2013. p. 264.

- ^ "Sefstat2022" (PDF).

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (25 October 2017). "Ethnic Origin (279), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census – 25% Sample Data". www12.statcan.gc.ca.

- ^ "Hungarians in Brazil". Archived from the original on 22 September 2007.

- ^ "Los obreros húngaros emigrados en América Latina entre las dos guerras mundiales. Ilona Varga" (PDF). www.ikl.org.pl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Thursday Top Ten: Top Ten Countries With The Largest Hungarian Diaspora In The World". 1 December 2016.

- ^ Hungary, About (19 November 2019). "Prime Minister Viktor Orbán's address at the 9th meeting of the Hungarian Diaspora Council". Prime Minister Viktor Orbán's address at the 9th meeting of the Hungarian Diaspora Council.

- ^ Discrimination in the EU in 2012 (PDF). Special Eurobarometer (Report). 383. European Commission. November 2012. p. 233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2013. The question asked was "Do you consider yourself to be...?" With a card showing: Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Other Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu, Atheist, and Non-believer/Agnostic. Space was given for Other (SPONTANEOUS) and DK. Jewish, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu did not reach the 1% threshold.

- ^ "Magyar". Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English Online. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ OED, s. v. "Ugrian": "Ugri, the name given by early Russian writers to a Finno-Ugric people dwelling east of the Ural Mountains".

- ^ a b Peter F. Sugar, ed. (22 November 1990). A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-253-20867-5. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ Edward Luttwak, The grand strategy of the Byzantine Empire, Harvard University Press, 2009, p. 156

- ^ György Balázs, Károly Szelényi, The Magyars: the birth of a European nation, Corvina, 1989, p. 8

- ^ Alan W. Ertl, Toward an Understanding of Europe: A Political Economic Précis of Continental Integration, Universal-Publishers, 2008, p. 358

- ^ Z. J. Kosztolnyik, Hungary under the early Árpáds: 890s to 1063, Eastern European Monographs, 2002, p. 3

- ^ Jenkins, Romilly James Heald (1967). De Administrando Imperio by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus. Corpus fontium historiae Byzantinae (New, revised ed.). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-88402-021-9. Retrieved 28 August 2013. According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, writing in his De Administrando Imperio (c. AD 950), "Patzinakia, the Pecheneg realm, stretches west as far as the Siret River (or even the Eastern Carpathian Mountains), and is four days distant from Tourkia (i.e. Hungary)."

- ^ Günter Prinzing; Maciej Salamon (1999). Byzanz und Ostmitteleuropa 950–1453: Beiträge zu einer table-ronde des XIX. International Congress of Byzantine Studies, Copenhagen 1996. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-447-04146-1. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Henry Hoyle Howorth (2008). History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century: The So-called Tartars of Russia and Central Asia. Cosimo, Inc. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-60520-134-4. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ Köpeczi, Béla; Makkai, László; Mócsy, András; Kiralý, Béla K.; Kovrig, Bennett; Szász, Zoltán; Barta, Gábor (2001). Transylvania in the medieval Hungarian kingdom (896–1526) (Volume 1 of History of Transylvania ed.). New York: Social Science Monographs, University of Michigan, Columbia University Press, East European Monographs. pp. 415–416. ISBN 0880334797.

- ^ A MAGYAROK TÜRK MEGNEVEZÉSE BÍBORBANSZÜLETETT KONSTANTINOS DE ADMINISTRANDOIMPERIO CÍMÛ MUNKÁJÁBAN – Takács Zoltán Bálint, SAVARIAA VAS MEGYEI MÚZEUMOK ÉRTESÍTÕJE28 SZOMBATHELY, 2004, pp. 317–333 [1]

- ^ Róna-Tas, András (1999). Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages. p. 273.

- ^ "Transylvania – The Roots of Ethnic Conflict". www.hungarianhistory.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Török, Tibor (26 June 2023). "Integrating Linguistic, Archaeological and Genetic Perspectives Unfold the Origin of Ugrians". Genes. 14 (7): 1345. doi:10.3390/genes14071345. PMC 10379071. PMID 37510249.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Obrusánszky, Borbála (2018). "Are the Hungarians Ugric?". In Angela Marcantonio (ed.). The state of the art of Uralic studies: tradition vs innovation (PDF). Sapienza Università Editrice. pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b c Gurkan, Cemal (8 January 2019). "On The Genetic Continuity of the Iron Age Pazyryk Culture: Geographic Distributions of the Paternal and Maternal Lineages from the Ak-Alakha-1 Burial". International Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (1). doi:10.31901/24566330.2019/19.01.709. ISSN 0972-3757.

- ^ a b c d e f Fóthi, Erzsébet; Gonzalez, Angéla; Fehér, Tibor; Gugora, Ariana; Fóthi, Ábel; Biró, Orsolya; Keyser, Christine (14 January 2020). "Genetic analysis of male Hungarian Conquerors: European and Asian paternal lineages of the conquering Hungarian tribes". Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. 12 (1): 31. Bibcode:2020ArAnS..12...31F. doi:10.1007/s12520-019-00996-0. ISSN 1866-9565. S2CID 210168662.

- ^ Nora Berend; Przemysław Urbańczyk; Przemysław Wiszewski (2013). "Hungarian 'pre-history' or 'ethnogenesis'?". Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c.900–c.1300. Cambridge University Press. p. 62.

- ^ Róna-Tas, András (1999). Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages. p. 96.

- ^ Blench, Roger; Matthew Briggs (1999). Archaeology and Language. Routledge. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-415-11761-6. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ^ Black, Jeremy; Brewer, Paul; Shaw, Anthony; Chandler, Malcolm; Cheshire, Gerard; Cranfield, Ingrid; Ralph Lewis, Brenda; Sutherland, Joe; Vint, Robert (2003). World History. Bath, Somerset: Parragon Books. p. 342. ISBN 0-75258-227-5.

- ^ a b c d e "Early History". A Country Study: Hungary. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 29 October 2004. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák, Tibor Frank, A History of Hungary, Indiana University Press, 1994 page 11. Google Books

- ^ "Magyars". Thenagain.info. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ a b c Szőke, Béla Miklós (2014). The Carolingian Age in the Carpathian Basin (PDF). Budapest: Hungarian National Museum. ISBN 978-615-5209-17-8.

- ^ a b c d e Szabados, György (2016). "Vázlat a magyar honfoglalás Kárpát-medencei hátteréről" [Outline of the background of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin] (PDF). Népek és kultúrák a Kárpát-medencében [Peoples and cultures in the Carpathian Basin] (in Hungarian). Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum. ISBN 978-615-5209-56-7.

- ^ a b c Szabados, György (2018). Folytonosság és/vagy találkozás? "Avar" és "magyar" a 9. századi Kárpát-medencében [Continuity and/or encounter? "Avar" and "Hungarian" in the 9th century Carpathian Basin] (in Hungarian).

- ^ a b Wang, Chuan-Chao; Posth, Cosimo; Furtwängler, Anja; Sümegi, Katalin; Bánfai, Zsolt; Kásler, Miklós; Krause, Johannes; Melegh, Béla (28 September 2021). "Genome-wide autosomal, mtDNA, and Y chromosome analysis of King Bela III of the Hungarian Arpad dynasty". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 19210. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1119210W. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-98796-x. PMC 8478946. PMID 34584164.

- ^ a b Sudár, Balázs; Petek, Zsolt (2016). Magyar őstörténet 4 – Honfoglalás és megtelepedés [Hungarian Prehistory 4 - Conquest and Settlement] (PDF). Helikon Kiadó, MTA BTK Magyar Őstörténeti Témacsoport (Hungarian Academy of Sciences – Hungarian Prehistory Research Team). ISBN 978-963-227-755-4.

- ^ a b c d e Révész, László (2014). The Era of the Hungarian Conquest (PDF). Budapest: Hungarian National Museum. ISBN 9786155209185.

- ^ Négyesi, Lajos; Veszprémy, László (2011). Gubcsi, Lajos (ed.). 1000-1100 years ago…Hungary in the Carpathian Basin (PDF). Budapest: MoD Zrínyi Média Ltd. ISBN 978-963-327-515-3.

- ^ a b c d Szabados, György (May 2022). "Álmostól Szent Istvánig" [From Álmos to Saint Stephen]. Rubicon (Hungarian Historical Information Dissemination) (in Hungarian).

- ^ a b c d e Endre, Neparáczki (28 July 2022). "A Magyarságkutató Intézet azon dolgozik, hogy fényt derítsen valódi származásunkra". Magyarságkutató Intézet (Institute of Hungarian Research) (in Hungarian).

- ^ Wang, Chuan-Chao; Posth, Cosimo; Furtwängler, Anja; Sümegi, Katalin; Bánfai, Zsolt; Kásler, Miklós; Krause, Johannes; Melegh, Béla (28 September 2021). "Genome-wide autosomal, mtDNA, and Y chromosome analysis of King Bela III of the Hungarian Arpad dynasty". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 19210. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1119210W. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-98796-x. PMC 8478946. PMID 34584164.

- ^ a b c Bóna, István (2001). "Conquest, Settlement, and Raids". History of Transylvania Volume I. From the Beginnings to 1606 - II. From Dacia to Erdőelve: Transylvania in the Period of the Great Migrations (271-896) - 7. Transylvania in the Period of the Hungarian Conquest and Foundation of a State. New York: Columbia University Press, (The Hungarian original by Institute of History Of The Hungarian Academy of Sciences). ISBN 0-88033-479-7.

- ^ Kosáry Domokos, Bevezetés a magyar történelem forrásaiba és irodalmába 1, p. 29

- ^ a b c d Történelem 5. az általános iskolások számára [History 5. for primary school students] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Oktatási Hivatal (Hungarian Educational Authority). 2020. pp. 15, 112, 116, 137, 138, 141. ISBN 978-615-6178-37-4.

- ^ a b Makoldi, Miklós (December 2021). "A magyarság származása" [The Origin of Hungarians] (PDF). Oktatási Hivatal (Office of Education) (in Hungarian).

- ^ a b Maár, Kitti; Varga, Gegely I.B.; Kovács, Bence; Schütz, Oszkár; Maróti, Zoltán; Kalmár, Tibor; Nyerki, Emil; Nagy, István; Latinovics, Dóra; Tihanyi, Balázs; Marcsik, Antónia; Pálfi, György; Bernert, Zsolt; Gallina, Zsolt; Varga, Sándor; Költő, László; Raskó, István; Török, Tibor; Neparáczki, Endre (23 March 2021). "Maternal Lineages from 10–11th Century Commoner Cemeteries of the Carpathian Basin". Genes. 12 (3): 460. doi:10.3390/genes12030460. PMC 8005002. PMID 33807111.

- ^ a b c d Maróti, Zoltán; Neparáczki, Endre; Schütz, Oszkár; Maár, Kitti; Varga, Gergely I.B.; Kovács, Bence; Kalmár, Tibor; Nyerki, Emil; Nagy, István; Latinovics, Dóra; Tihanyi, Balázs; Marcsik, Antónia; Pálfi, György; Bernert, Zsolt; Gallina, Zsolt; Horváth, Ciprián; Varga, Sándor; Költő, László; Raskó, István; Nagy, Péter L.; Balogh, Csilla; Zink, Albert; Maixner, Frank; Götherström, Anders; George, Robert; Szalontai, Csaba; Szenthe, Gergely; Gáll, Erwin; Kiss, Attila P.; Gulyás, Bence; Kovacsóczy, Bernadett Ny.; Gál, Sándor Szilárd; Tomka, Péter; Török, Tibor (25 May 2022). "The genetic origin of Huns, Avars, and conquering Hungarians". Current Biology. 32 (13): 2858–2870.e7. Bibcode:2022CBio...32E2858M. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.04.093. PMID 35617951. S2CID 246191357.

- ^ Neparáczki, Endre; Maróti, Zoltán; Kalmár, Tibor; Maár, Kitti; Nagy, István; Latinovics, Dóra; Kustár, Ágnes; Pálfi, György; Molnár, Erika; Marcsik, Antónia; Balogh, Csilla; Lőrinczy, Gábor; Gál, Szilárd Sándor; Tomka, Péter; Kovacsóczy, Bernadett; Kovács, László; Raskó, István; Török, Tibor (12 November 2019). "Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 16569. Bibcode:2019NatSR...916569N. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53105-5. PMC 6851379. PMID 31719606.

- ^ Triska, Petr; Chekanov, Nikolay; Stepanov, Vadim; Khusnutdinova, Elza K.; Kumar, Ganesh Prasad Arun; Akhmetova, Vita; Babalyan, Konstantin; Boulygina, Eugenia; Kharkov, Vladimir; Gubina, Marina; Khidiyatova, Irina; Khitrinskaya, Irina; Khrameeva, Ekaterina E.; Khusainova, Rita; Konovalova, Natalia (28 December 2017). "Between Lake Baikal and the Baltic Sea: genomic history of the gateway to Europe". BMC Genetics. 18 (Suppl 1): 110. doi:10.1186/s12863-017-0578-3. ISSN 1471-2156. PMC 5751809. PMID 29297395.

- ^ a b "Evidence of the Hun-Avar-Hungarian kinship rewrites our knowledge about the Hungarian conquest". Institute of Hungarian Research. 12 October 2022.

- ^ Szeifert, Bea; Gerber, Daniel; Csáky, Veronika; Langó, Péter; Stashenkov, Dmitrii; Khokhlov, Aleksandr; Sitdikov, Ayrat; Gazimzyanov, Ilgizar (9 May 2022). "Tracing genetic connections of ancient Hungarians to the 6th-14th century populations of the Volga-Ural region". Human Molecular Genetics. 31 (19): 3266–3280. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddac106. PMC 9523560. PMID 35531973.

- ^ a b Horváth-Lugossy, Gábor; Makoldi, Miklós; Neparáczki, Endre (2022). Kings and Saints – The Age of the Árpáds (PDF). Budapest, Székesfehérvár: Institute of Hungarian Research. ISBN 978-615-6117-65-6.

- ^ a b c Neparáczki, Endre; Maróti, Zoltán; Kalmár, Tibor; Maár, Kitti; Nagy, István; Latinovics, Dóra; Kustár, Ágnes; Pálfi, György; Molnár, Erika; Marcsik, Antónia; Balogh, Csilla; Lőrinczy, Gábor; Tomka, Péter; Kovacsóczy, Bernadett; Kovács, László; Török, Tibor (12 November 2019). "Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 16569. Bibcode:2019NatSR...916569N. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53105-5. PMC 6851379. PMID 31719606.

- ^ a b c Neparáczki, Endre; Maróti, Zoltán; Kalmár, Tibor; Kocsy, Klaudia; Maár, Kitti; Bihari, Péter; Nagy, István; Fóthi, Erzsébet; Pap, Ildikó; Kustár, Ágnes; Pálfi, György; Raskó, István; Zink, Albert; Török, Tibor (18 October 2018). "Mitogenomic data indicate admixture components of Central-Inner Asian and Srubnaya origin in the conquering Hungarians". PLOS ONE. 13 (10): e0205920. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1305920N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205920. PMC 6193700. PMID 30335830.

- ^ "The Gesta Hungarorum of Anonymus, Notary of King Béla" (PDF). Translated by Martyn Rady. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ Négyesi, Lajos; Veszprémy, László (2011). Gubcsi, Lajos (ed.). 1000-1100 years ago…Hungary in the Carpathian Basin (PDF). Budapest: MoD Zrínyi Média Ltd. ISBN 978-963-327-515-3.

- ^ Tóth, Sándor László (1998). Levédiától a Kárpát-medencéig [From Levedia to the Carpathian Basin] (in Hungarian). Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. ISBN 963-482-175-8.

- ^ Peter F. Sugar (1994). A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-253-20867-5. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ Kalti, Mark. Chronicon Pictum (in Hungarian).

- ^ Csorba, Csaba (1997). Árpád népe [The people of Árpád] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Kulturtrade kiadó. ISBN 978-963-9069-20-6. ISSN 1417-6114.

- ^ Koperski, A.: Przemyśl (Lengyelország). In: A honfoglaló magyarság. Kiállítási katalógus. Bp. 1996. pp. 439–448.

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe. M. E. Sharpe, Armonk, NY and London, England, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5.

- ^ "Szekler people". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Stephen Wyley. "The Hungarians of Hungary". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ "History of Hungary, 895–970". Zum.de. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- ^ Historical World Atlas. With the commendation of the Royal Geographical Society. Carthographia, Budapest, Hungary, 2005. ISBN 978-963-352-002-4 CM

- ^ a b Őri, Péter; Kocsis, Károly; Faragó, Tamás; Tóth, Pál Péter (2021). "History of Population" (PDF). In Kocsis, Károly; Őri, Péter (eds.). National Atlas of Hungary – Volume 3 – Society. Budapest: Eötvös Loránd Research Network (ELKH), Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences (CSFK), Geographical Institute. ISBN 978-963-9545-64-9.

- ^ a b Kocsis, Károly; Tátrai, Patrik; Agárdi, Norbert; Balizs, Dániel; Kovács, Anikó; Gercsák, Tibor; Klinghammer, István; Tiner, Tibor (2015). Changing Ethnic Patterns of the Carpatho–Pannonian Area from the Late 15th until the Early 21st Century – Accompanying Text (PDF) (in Hungarian and English) (3rd ed.). Budapest: Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Geographical Institute. ISBN 978-963-9545-48-9.

((cite book)): CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Macartney, Carlile Aylmer (1962), "5. The Eighteenth Century", Hungary; A short history, University Press, retrieved 3 August 2016

- ^ "Chapter 1. Historical Setting". A Country Study: Hungary. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 21. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ Lee, Jonathan; Robert Siemborski. "Peaks/waves of immigration". bergen.org. Archived from the original on 16 June 1997.

- ^ Kocsis, Károly (1998). "Introduction". Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin. Simon Publications LLC. ISBN 978-1-931313-75-9. Retrieved 21 May 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bugajski, Janusz (1995). Ethnic Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations, and Parties. M.E. Sharpe (Washington, D.C.). ISBN 978-1-56324-283-0.

- ^ Kovrig, Bennett (2000), Partitioned nation: Hungarian minorities in Central Europe, in: Michael Mandelbaum (ed.), The new European Diasporas: National Minorities and Conflict in Eastern Europe, New York City: Council on Foreign Relations Press, pp. 19–80.

- ^ Raffay Ernő: A vajdaságoktól a birodalomig. Az újkori Románia története (From voivodeships to the empire. The modern history of Romania). Publishing house JATE Kiadó, Szeged, 1989, pp. 155–156)

- ^ a b "Nyolcmillió lehet a magyar népesség 2050-re". origo. 14 April 2005. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- ^ Hungary: Transit Country Between East and West. Migration Information Source. November 2003.

- ^ Veronika Gulyas (26 May 2010). "Hungary Citizenship Bill Irks Neighbor". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b c Endre, Neparáczki (22 August 2022). "Saint László is more Asian than most of our kings". Magyarságkutató Intézet (Institute of Hungarian Research).

- ^ Saag, Lehti; Staniuk, Robert (11 July 2022). "Historical human migrations: From the steppe to the basin". Current Biology. 32 (13): 38–41. Bibcode:2022CBio...32.R738S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.05.058. PMID 35820383. S2CID 250443139.

- ^ Horváth-Lugossy, Gábor; Makoldi, Miklós; Neparáczki, Endre (2022). Kings and Saints - The Age of the Árpáds (PDF). Budapest, Székesfehérvár: Institute of Hungarian Research. ISBN 978-615-6117-65-6.

- ^ György, Szabados (1998). "A krónikáktól a Gestáig – Az előidő-szemlélet hangsúlyváltásai a 15–18. században" [From the chronicles to the Gesta - Shifts in emphasis of the pre-time perspective in the 15th–18th centuries]. Irodalomtörténeti Közlemények 1998. 102. évf. 5-6. füzet [Bulletins of Literary History 1998, Vol. 102, Booklets 5-6] (in Hungarian). MTA Irodalomtudományi Intézet (Institute for Literary Studies of Hungarian Academy of Sciences). pp. 615–641. ISSN 0021-1486.

- ^ Szűcs 1999, p. xliv; Engel 2001, p. 2; Lendvai 2003, p. 7; Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 386.

- ^ Keyser, Christine; Zvénigorosky, Vincent; Gonzalez, Angéla; Fausser, Jean-Luc; Jagorel, Florence; Gérard, Patrice; Tsagaan, Turbat; Duchesne, Sylvie; Crubézy, Eric; Ludes, Bertrand (30 July 2020). "Genetic evidence suggests a sense of family, parity and conquest in the Xiongnu Iron Age nomads of Mongolia". Human Genetics. 140 (2): 349–359. doi:10.1007/s00439-020-02209-4. PMID 32734383. S2CID 253981964.

East Eurasian R1a subclades R1a1a1b2a-Z94 and R1a1a1b2a2-Z2124 were a common element of the Hun, Avar and Hungarian Conqueror elite and very likely belonged to the branch that was observed in our Xiongnu samples. Moreover, haplogroups Q1a and N1a were also major components of these nomadic groups, reinforcing the view that Huns (and thus Avars and Hungarian invaders) might derive from the Xiongnu as was proposed until the eighteenth century but strongly disputed since.

- ^ Quiles, Carlos (2 August 2020). "Xiongnu Y-DNA connects Huns & Avars to Scytho-Siberians". Indo-European.eu.

- ^ Varga, Gergely I B; Kristóf, Lilla Alida; Maár, Kitti; Kis, Luca; Schütz, Oszkár; Váradi, Orsolya; Kovács, Bence; Gînguță, Alexandra; Tihanyi, Balázs; Nagy, Péter L; Maróti, Zoltán; Nyerki, Emil; Török, Tibor; Neparáczki, Endre (January 2023). "The archaeogenomic validation of Saint Ladislaus' relic provides insights into the Árpád dynasty's genealogy". Journal of Genetics and Genomics = Yi Chuan Xue Bao. 50 (1): 58–61. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2022.06.008. PMID 35809778.

- ^ Peltola, Sanni; Majander, Kerttu; Makarov, Nikolaj; Dobrovolskaya, Maria; Nordqvist, Kerkko; Salmela, Elina; Onkamo, Päivi (9 January 2023). "Genetic admixture and language shift in the medieval Volga-Oka interfluve". Current Biology. 33 (1): 174–182.e10. Bibcode:2023CBio...33E.174P. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.11.036. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 36513080.

- ^ a b Kharkov, V.N.; Kolesnikov, N.A.; Valikhova, L.V.; Zarubin, A.A.; Svarovskaya, M.G.; Marusin, A.V.; Khitrinskaya, I.Yu.; Stepanov, V.A. (March 2023). "Relationship of the gene pool of the Khants with the peoples of Western Siberia, Cis-Urals and the Altai-Sayan Region according to the data on the polymorphism of autosomic locus and the Y-chromosome". Vavilov Journal of Genetics and Breeding. 27 (1): 46–54. doi:10.18699/VJGB-23-07. ISSN 2500-0462. PMC 10009483. PMID 36923476.

- ^ Wang, Ke; Yu, He; Radzevičiūtė, Rita; Kiryushin, Yuriy F.; Tishkin, Alexey A.; Frolov, Yaroslav V.; Stepanova, Nadezhda F.; Kiryushin, Kirill Yu.; Kungurov, Artur L.; Shnaider, Svetlana V.; Tur, Svetlana S.; Tiunov, Mikhail P.; Zubova, Alisa V.; Pevzner, Maria; Karimov, Timur (6 February 2023). "Middle Holocene Siberian genomes reveal highly connected gene pools throughout North Asia". Current Biology. 33 (3): 423–433.e5. Bibcode:2023CBio...33E.423W. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.11.062. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 36638796. S2CID 255750546.

- ^ Vidaković, Nenad (30 April 2012). "From the Ethnic History of Asia – the Dōnghú, Wūhuán and Xiānbēi Proto-Mongolian Tribes". Migracijske i etničke teme (in Croatian). 28 (1): 75–95. ISSN 1333-2546. "Other types of sources on the history of the Proto-Mongolian tribes are archaeological findings, which associate Mongolian ethnogenesis with slab grave cultures and the Lower Xiàjiādiàn."

- ^ Savelyev, Alexander; Jeong, Choongwon (7 May 2020). "Early nomads of the Eastern Steppe and their tentative connections in the West". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2: E20. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.18. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 7612788. PMID 35663512.

- ^ Jeong, Choongwon; Wang, Ke; Wilkin, Shevan; Taylor, William Timothy Treal; Miller, Bryan K.; Bemmann, Jan H.; Stahl, Raphaela; Chiovelli, Chelsea; Knolle, Florian; Ulziibayar, Sodnom; Khatanbaatar, Dorjpurev; Erdenebaatar, Diimaajav; Erdenebat, Ulambayar; Ochir, Ayudai; Ankhsanaa, Ganbold; Vanchigdash, Chuluunkhuu; Ochir, Battuga; Munkhbayar, Chuluunbat; Tumen, Dashzeveg; Kovalev, Alexey; Kradin, Nikolay; Bazarov, Bilikto A.; Miyagashev, Denis A.; Konovalov, Prokopiy B.; Zhambaltarova, Elena; Miller, Alicia Ventresca; Haak, Wolfgang; Schiffels, Stephan; Krause, Johannes; Boivin, Nicole; Erdene, Myagmar; Hendy, Jessica; Warinner, Christina (12 November 2020). "A Dynamic 6,000-Year Genetic History of Eurasia's Eastern Steppe". Cell. 183 (4): 890–904. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.015. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 7664836. PMID 33157037.

- ^ Tambets, Kristiina; Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Hudjashov, Georgi; Ilumäe, Anne-Mai; Rootsi, Siiri; Honkola, Terhi; Vesakoski, Outi; Atkinson, Quentin; Skoglund, Pontus; Kushniarevich, Alena; Litvinov, Sergey; Reidla, Maere; Metspalu, Ene; Saag, Lehti; Rantanen, Timo (21 September 2018). "Genes reveal traces of common recent demographic history for most of the Uralic-speaking populations". Genome Biology. 19 (1): 139. doi:10.1186/s13059-018-1522-1. ISSN 1474-760X. PMC 6151024. PMID 30241495.

- ^ Post, Helen; Németh, Endre; Klima, László; Flores, Rodrigo; Fehér, Tibor; Türk, Attila; Székely, Gábor; Sahakyan, Hovhannes; Mondal, Mayukh; Montinaro, Francesco; Karmin, Monika (24 May 2019). "Y-chromosomal connection between Hungarians and geographically distant populations of the Ural Mountain region and West Siberia". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 7786. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.7786P. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44272-6. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6534673. PMID 31127140.

- ^ Wong, Emily H.M. (2015). "Reconstructing genetic history of Siberian and Northeastern European populations". Genome Research. 27 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1101/gr.202945.115. PMC 5204334. PMID 27965293.

- ^ a b Triska, Petr; Chekanov, Nikolay; Stepanov, Vadim; Khusnutdinova, Elza K.; Kumar, Ganesh Prasad Arun; Akhmetova, Vita; Babalyan, Konstantin; Boulygina, Eugenia; Kharkov, Vladimir; Gubina, Marina; Khidiyatova, Irina; Khitrinskaya, Irina; Khrameeva, Ekaterina E.; Khusainova, Rita; Konovalova, Natalia (28 December 2017). "Between Lake Baikal and the Baltic Sea: genomic history of the gateway to Europe". BMC Genetics. 18 (1): 110. doi:10.1186/s12863-017-0578-3. ISSN 1471-2156. PMC 5751809. PMID 29297395.

- ^ Bjørn, Rasmus G. (2022). "Indo-European loanwords and exchange in Bronze Age Central and East Asia: Six new perspectives on prehistoric exchange in the Eastern Steppe Zone". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 4: e23. doi:10.1017/ehs.2022.16. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 10432883. PMID 37599704. S2CID 248358873.

- ^ Endre Neparacki, A honfoglalók genetikai származásának és rokonsági viszonyainak vizsgálata archeogenetikai módszerekkel, ELTE TTK Biológia Doktori Iskola, 2017, pp. 61–65

- ^ Neparáczki, Endre; Juhász, Zoltán; Pamjav, Horolma; Fehér, Tibor; Csányi, Bernadett; Zink, Albert; Maixner, Frank; Pálfi, György; Molnár, Erika; Pap, Ildikó; Kustár, Ágnes; Révész, László; Raskó, István; Török, Tibor (February 2017). "Genetic structure of the early Hungarian conquerors inferred from mtDNA haplotypes and Y-chromosome haplogroups in a small cemetery". Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 292 (1): 201–214. doi:10.1007/s00438-016-1267-z. PMID 27803981. S2CID 4099313.

- ^ Neparáczki, Endre; Maróti, Zoltán; Kalmár, Tibor; Kocsy, Klaudia; Maár, Kitti; Bihari, Péter; Nagy, István; Fóthi, Erzsébet; Pap, Ildikó; Kustár, Ágnes; Pálfi, György; Raskó, István; Zink, Albert; Török, Tibor (18 October 2018). Caramelli, David (ed.). "Mitogenomic data indicate admixture components of Central-Inner Asian and Srubnaya origin in the conquering Hungarians". PLOS ONE. 13 (10). Public Library of Science (PLoS): e0205920. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1305920N. bioRxiv 10.1101/250688. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205920. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6193700. PMID 30335830. S2CID 90886641.

- ^ Wong, Emily H.M. (2015). "Reconstructing genetic history of Siberian and Northeastern European populations". Genome Research. 27 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1101/gr.202945.115. PMC 5204334. PMID 27965293.

- ^ Engel, Pál (2001). Ayton, Andrew (ed.). The realm of St. Stephen: a history of medieval Hungary, 895 - 1526. International library of historical studies. London: Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-061-2.

- ^ "J . SZŰCS: THEORETICAL ELEMENTS IN MASTER SIMON OF KÉZA'S GESTA HUNGARORUM (1282-1285)", Gesta Hungarorum, Central European University Press, pp. xxix–cii, 1 January 1999, doi:10.1515/9789633865699-005, ISBN 978-963-386-569-9

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen, Otto J. (31 December 1973). Knight, Max (ed.). "The World of the Huns". University of California Press: 386. doi:10.1525/9780520310773. ISBN 9780520310773.

- ^ Keyser et al. 2020, pp. 1, 8–9. "[O]ur findings confirmed that the Xiongnu had a strongly admixed mitochondrial and Y-chromosome gene pools and revealed a significant western component in the Xiongnu group studied.... [W]e propose Scytho-Siberians as ancestors of the Xiongnu and Huns as their descendants... [E]ast Eurasian R1a subclades R1a1a1b2a-Z94 and R1a1a1b2a2-Z2124 were a common element of the Hun, Avar and Hungarian Conqueror elite and very likely belonged to the branch that was observed in our Xiongnu samples. Moreover, haplogroups Q1a and N1a were also major components of these nomadic groups, reinforcing the view that Huns (and thus Avars and Hungarian invaders) might derive from the Xiongnu as was proposed until the eighteenth century but strongly disputed since... Some Xiongnu paternal and maternal haplotypes could be found in the gene pool of the Huns, the Avars, as well as Mongolian and Hungarian conquerors."

- ^ Pamjav, H; Dudás, E; Krizsán, K; Galambos, A (December 2019). "A Y-chromosomal study of mansi population from konda River Basin in Ural". Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series. 7 (1): 602–603. doi:10.1016/j.fsigss.2019.10.106. ISSN 1875-1768. S2CID 208581616.

- ^ Pamjav, Horolma; Fóthi, Á.; Fehér, T.; Fóthi, Erzsébet (1 August 2017). "A study of the Bodrogköz population in north-eastern Hungary by Y chromosomal haplotypes and haplogroups". Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 292 (4): 883–894. doi:10.1007/s00438-017-1319-z. PMID 28409264. S2CID 10107799.

- ^ Csányi, B.; Bogácsi-Szabó, E.; Tömöry, Gy.; Czibula, Á.; Priskin, K.; Csõsz, A.; Mende, B.; Langó, P.; Csete, K.; Zsolnai, A.; Conant, E. K.; Downes, C. S.; Raskó, I. (July 2008). "Y-Chromosome Analysis of Ancient Hungarian and Two Modern Hungarian-Speaking Populations from the Carpathian Basin". Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (4): 519–534. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00440.x. PMID 18373723. S2CID 13217908.

- ^ Semino 2000 et al[full citation needed]

- ^ Bíró, András; Fehér, Tibor; Bárány, Gusztáv; Pamjav, Horolma (March 2015). "Testing Central and Inner Asian admixture among contemporary Hungarians". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 15: 121–126. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2014.11.007. PMID 25468443.

- ^ Nagy, P.L.; Olasz, J.; Neparáczki, E.; et al. (2020), "Determination of the phylogenetic origins of the Árpád Dynasty based on Y chromosome sequencing of Béla the Third", European Journal of Human Genetics, 29 (1): 164–172, doi:10.1038/s41431-020-0683-z, PMC 7809292, PMID 32636469

- ^ "R-SUR51 Y-DNA Haplogroup". YFull.

- ^ Sample DA129 ERS2374372 Nomad_IA Tian Shan; R1a-Y2632 137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes

- ^ a b Maróti, Zoltán; Neparáczki, Endre; Schütz, Oszkár; Maár, Kitti; Varga, Gergely I. B.; Kovács, Bence; Kalmár, Tibor; Nyerki, Emil; Nagy, István; Latinovics, Dóra; Tihanyi, Balázs (20 January 2022). "Whole genome analysis sheds light on the genetic origin of Huns, Avars and conquering Hungarians". bioRxiv 10.1101/2022.01.19.476915.

- ^ Zhang, Fan; Ning, Chao; Scott, Ashley; Fu, Qiaomei; Bjørn, Rasmus; Li, Wenying; Wei, Dong; Wang, Wenjun; Fan, Linyuan; Abuduresule, Idilisi; Hu, Xingjun; Ruan, Qiurong; Niyazi, Alipujiang; Dong, Guanghui; Cao, Peng (2021). "The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies". Nature. 599 (7884): 256–261. Bibcode:2021Natur.599..256Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04052-7. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 8580821. PMID 34707286.

- ^ A nyelv és a nyelvek ("Language and languages"), edited by István Kenesei. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 2004, ISBN 963-05-7959-6, p. 134)

- ^ Ethnic Continuity in the Carpatho-Danubian Area, Elemér Illyés

- ^ "Browse Hungary's detailed ethnographic map made for the Treaty of Trianon online". dailynewshungary.com. 9 May 2017.

- ^ Spatiul istoric si etnic romanesc, Editura Militara, Bucuresti, 1992

Sources

[edit]- Keyser, Christine; et al. (30 July 2020). "Genetic evidence suggests a sense of family, parity and conquest in the Xiongnu Iron Age nomads of Mongolia". Human Genetics. 557 (7705). Springer: 369–373. doi:10.1007/s00439-020-02209-4. PMID 32734383. S2CID 220881540. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- Molnar, Miklos (2001). A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge Concise Histories (Fifth printing 2008 ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66736-4.

- Korai Magyar Történeti Lexicon (9–14. század) (Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th Centuries)) Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó; 753. ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

- Károly Kocsis (DSc, University of Miskolc) – Zsolt Bottlik (PhD, Budapest University) – Patrik Tátrai: Etnikai térfolyamatok a Kárpát-medence határon túli régióiban + CD (for detailed data), Magyar Tudományos Akadémia (Hungarian Academy of Sciences) – Földrajtudományi Kutatóintézet (Academy of Geographical Studies); Budapest; 2006.; ISBN 963-9545-10-4

- Lendvai, Paul (2003). The Hungarians: A Thousand Years of Victory in Defeat. Translated by Major, Ann. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400851522.

- Neparáczki, Endre; et al. (12 November 2019). "Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports. 9 (16569). Nature Research: 16569. Bibcode:2019NatSR...916569N. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53105-5. PMC 6851379. PMID 31719606.

- Szűcs, Jenő (1999). "Theoretical Elements in Master Simon of Kéza's Gesta Hungarorum (1282–1285)". In László Veszprémy; Frank Schaer (eds.). Simon of Kéza: Deeds of the Hungarians. Central European University Press. pp. xxix–cii.

As of this edit, this article uses content from "A Y-chromosomal study of mansi population from konda River Basin in Ural", which is licensed in a way that permits reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, but not under the GFDL. All relevant terms must be followed.

External links

[edit]- Origins of the Hungarians from the Enciklopédia Humana (with many maps and pictures)

- Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin

- Hungary and the Council of Europe

- Facts about Hungary Archived 22 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Hungarians outside Hungary – Map

Genetic studies

- MtDNA and Y chromosome polymorphisms in Hungary: inferences from the Palaeolithic, Neolithic and Uralic influences on the modern Hungarian gene pool

- Guglielmino, CR; De Silvestri, A; Beres, J (March 2000). "Probable ancestors of Hungarian ethnic groups: an admixture analysis". Annals of Human Genetics. 64 (Pt 2): 145–59. doi:10.1017/S0003480000008010. PMID 11246468.

- Human Chromosomal Polymorphism in a Hungarian Sample

- Hungarian genetics researches 2008–2009 (in Hungarian)

| History |

|  | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geography | ||||||

| Politics | ||||||

| Economy | ||||||

| Society |

| |||||

Peoples speaking Uralic languages | |

|---|---|

| Baltic Finns | |

| Sámi | |

| Volga Finns | |

| Permians | |

| Ob-Ugrians | |

| Hungarians | |

| Samoyeds | |

![Kniezsa's (1938) view on the ethnic map of the Kingdom of Hungary in the 11th century, based on toponyms. Kniezsa's view has been criticized by many scholars, because of its non-compliance with later archaeological and onomastics research, but his map is still regularly cited in modern reliable sources. One of the most prominent critics of this map was Emil Petrovici.[136]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3b/Ethnic_map_of_11th_century.jpg/150px-Ethnic_map_of_11th_century.jpg)

![The "Red Map",[137] based on the 1910 census. Regions with population density below 20 persons/km2 (52 persons/sq mi)[138] are left blank and the corresponding population is represented in the nearest region with population density above that limit. Red colour to mark Hungarians and light purple colour to mark Romanians.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/f/f4/Redmap.jpg/150px-Redmap.jpg)