Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor | |

|---|---|

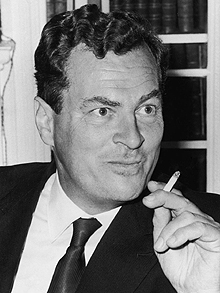

Leigh Fermor in 1966 | |

| Born | Patrick Michael Leigh Fermor 11 February 1915 London, England |

| Died | 10 June 2011 (aged 96) Dumbleton, England |

| Occupation | Author, scholar and soldier |

| Nationality | British |

| Genre | Travel |

| Notable works | A Time of Gifts, Abducting a General |

| Notable awards | Knight Bachelor; Distinguished Service Order; Officer of the Order of the British Empire |

| Spouse | |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1940–1946 |

| Rank | Major |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Order Officer of the Order of the British Empire |

Sir Patrick Michael Leigh Fermor DSO OBE (11 February 1915 – 10 June 2011) was an English writer, scholar, soldier and polyglot.[1] He played a prominent role in the Cretan resistance during the Second World War,[2] and was widely seen as Britain's greatest living travel writer, on the basis of books such as A Time of Gifts (1977).[3] A BBC journalist once termed him "a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene".[4]

Early life and education

[edit]Leigh Fermor was born in London, the son of Sir Lewis Leigh Fermor, a distinguished geologist, and Muriel Aeyleen (Eileen), daughter of Charles Taafe Ambler.[5] Shortly after his birth, his mother and sister left to join his father in India, leaving the infant Patrick in England with a family in Northamptonshire: first in the village of Weedon, and later in nearby Dodford. He did not meet his parents or his sister again until he was four years old. As a child Leigh Fermor had problems with academic structure and limitations, and was sent to a school for "difficult" children. He was later expelled from The King's School, Canterbury after he was caught holding hands with a greengrocer's daughter. At school he also became friendly with another contemporary Alan Watts.[6]

His last report from The King's School noted that the young Leigh Fermor was "a dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness".[7] He continued learning by reading texts on Greek, Latin, Shakespeare and history, with the intention of entering the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Gradually he changed his mind, deciding to become an author instead, and in the summer of 1933 relocated to Shepherd Market in London, living with a few friends. Soon, faced with the challenges of an author's life in London and rapidly draining finances, he decided to leave for Europe.[8]

Early travels

[edit]At the age of 18 Leigh Fermor decided to walk the length of Europe from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople (Istanbul).[9] He set off on 8 December 1933 with a few clothes, several letters of introduction, the Oxford Book of English Verse and a Loeb volume of Horace's Odes. He slept in barns and shepherds' huts, but was also invited by gentry and aristocracy into the country houses of Central Europe. He experienced hospitality in many monasteries along the way.

Two of his later travel books, A Time of Gifts (1977) and Between the Woods and the Water (1986), cover this journey, but at the time of his death, a book on the final part of his journey remained unfinished. This was edited and assembled from Leigh Fermor's diary of the time and an early draft he wrote in the 1960s. It was published as The Broken Road by John Murray in September 2013.[10]

Leigh Fermor arrived in Istanbul on 1 January 1935, then continued to travel around Greece, spending a few weeks in Mount Athos. In March he was involved in the campaign of royalist forces in Macedonia against an attempted Republican revolt. In Athens, he met Balasha Cantacuzène (Bălaşa Cantacuzino), a Romanian Phanariote noblewoman, with whom he fell in love. They shared an old watermill outside the city looking out towards Poros, where she painted and he wrote. They moved on to Băleni, Galați, the Cantacuzène house in Moldavia, Romania, where he remained until the autumn of 1939.[2] On learning that Britain had declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939 Leigh Fermor immediately left Romania for home and enlisted in the army.[11] He did not meet Cantacuzène again until 1965.[12]

Second World War

[edit]

As an officer cadet Leigh Fermor trained alongside Derek Bond[13] and Iain Moncreiffe. He later joined the Irish Guards. His knowledge of modern Greek gained him a commission in the General List in August 1940[14] and he became a liaison officer in Albania. He fought in Crete and mainland Greece. During the German occupation, he returned to Crete three times, once by parachute, and was among a small number of Special Operations Executive (SOE) officers posted to organise the island's resistance to the occupation. Disguised as a shepherd and nicknamed Michalis or Filedem, he lived for over two years in the mountains. With Captain Bill Stanley Moss as his second in command, Leigh Fermor led the party that in 1944 captured and evacuated the German commander, Major General Heinrich Kreipe.[15] There is a memorial commemorating Kreipe's abduction near Archanes in Crete.[16]

Moss featured the events of the Cretan capture in his book Ill Met by Moonlight.[7] (The 2014 edition contains an afterword on the context, written by Leigh Fermor in 2001.) It was adapted in a film by the same name, directed/produced by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger and released in 1957 with Leigh Fermor played by Dirk Bogarde.[2] Leigh Fermor's own account Abducting A General – The Kreipe Operation and SOE in Crete appeared in October 2014.[17][18]

During periods of leave, Leigh Fermor spent time at Tara, a villa in Cairo rented by Moss, where the "rowdy household" of SOE officers was presided over by Countess Zofia (Sophie) Tarnowska.[2]

Wartime honours

[edit]

- Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE)[19]

- The Distinguished Service Order (DSO)[20]

- Honorary Citizen of Heraklion, of Kardamyli and of Gytheio

Post-war

[edit]In 1950 Leigh Fermor published his first book, The Traveller's Tree, about his post-war travels in the Caribbean, which won the Heinemann Foundation Prize for Literature and established his career. The reviewer in The Times Literary Supplement wrote: "Mr Leigh Fermor never loses sight of the fact, not always grasped by superficial visitors, that most of the problems of the West Indies are the direct legacy of the slave trade."[21] It was quoted extensively in Live and Let Die, by Ian Fleming.[22] He went on to write several other books of his journeys, including Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese and Roumeli, of his travels on mule and foot around remote parts of Greece.

Leigh Fermor translated the manuscript The Cretan Runner written by George Psychoundakis, a dispatch runner on Crete during the war, and helped Psychoundakis get his work published. Leigh Fermor also wrote a novel, The Violins of Saint-Jacques, which was adapted as an opera by Malcolm Williamson. His friend Lawrence Durrell recounts in his book Bitter Lemons (1957) how in 1955, during the Cyprus Emergency, Leigh Fermor visited Durrell's villa in Bellapais, Cyprus:

After a splendid dinner by the fire he starts singing, songs of Crete, Athens, Macedonia. When I go out to refill the ouzo bottle.... I find the street completely filled with people listening in utter silence and darkness. Everyone seems struck dumb. 'What is it?' I say, catching sight of Frangos. 'Never have I heard of Englishmen singing Greek songs like this!' Their reverent amazement is touching; it is as if they want to embrace Paddy wherever he goes.[23]

Later years

[edit]After living with her for many years, Leigh Fermor was married in 1968 to the Honourable Joan Elizabeth Rayner (née Eyres Monsell), daughter of Bolton Eyres-Monsell, 1st Viscount Monsell. She accompanied him on many travels until her death in Kardamyli in June 2003, aged 91. They had no children.[24] They lived part of the year in a house in an olive grove near Kardamyli in the Mani Peninsula, southern Peloponnese, and part of the year in Gloucestershire.

In 2007, he said that, for the first time, he had decided to work using a typewriter, having written all his books longhand until then.[3]

Leigh Fermor opened his home in Kardamyli to the local villagers on his saint's day, which was 8 November, the feast of Michael (he had assumed the name Michael while fighting with the Greek resistance).[25] New Zealand writer Maggie Rainey-Smith (staying in the area while researching for her next book) joined in his saint's day celebration in November 2007, and after his death, posted some photographs of the event.[26][27] The house at Kardamyli features in the 2013 film Before Midnight.[28]

Leigh Fermor influenced a generation of British travel writers, including Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Philip Marsden, Nicholas Crane and Rory Stewart.[29]

Death and funeral

[edit]Leigh Fermor was noted for his strong physical constitution, even though he smoked 80 to 100 cigarettes a day.[30] Although in his last years he suffered from tunnel vision and wore hearing aids and an eyepatch, he remained physically fit up to his death and dined at table on the last evening of his life.

For the last few months of his life Leigh Fermor suffered from a cancerous tumour, and in early June 2011 he underwent a tracheotomy in Greece. As death was close, according to local Greek friends, he expressed a wish to visit England to bid goodbye to his friends, and then return to die in Kardamyli, though it is also stated that he actually wished to die in England and be buried next to his wife.[31]

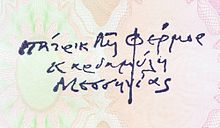

Leigh Fermor died in England aged 96, on 10 June 2011, the day after his return.[32] His funeral was held at St Peter's Church, Dumbleton, Gloucestershire, on 16 June 2011. A Guard of Honour was provided by serving and former members of the Intelligence Corps, and a bugler from the Irish Guards sounded the Last Post and Reveille. He is buried next to his wife in the churchyard there. The Greek inscription is a quotation from Cavafy[33] translatable as "In addition, he was that best of all things, Hellenic".

Awards and honours

[edit]

- 1950, Heinemann Foundation Prize for Literature for The Traveller's Tree

- 1978, WH Smith Literary Award for A Time of Gifts

- 1991, elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature[34]

- 1991, awarded the title Companion of Literature by the Royal Society of Literature[35]

- 1995, Chevalier, Ordre des Arts et des Lettres[36]

- February 2004, accepted the knighthood (Knight Bachelor), which he had declined in 1991[37][38]

- 2004, awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award of the British Guild of Travel Writers

- 2007, the Greek government made him Commander of the Order of the Phoenix[3]

- His life and work were profiled by the travel writer Benedict Allen in the documentary series Travellers' Century (2008) on BBC Four

- A documentary film on the Cretan resistance The 11th Day (2003) contains extensive interview segments with Leigh Fermor recounting his service in the S.O.E. and his activities on Crete, including the capture of General Kreipe.

Legacy

[edit]A Patrick Leigh Fermor Society formed in 2014.[39]

The National Archives in London holds copies of Leigh Fermor's wartime dispatches from occupied Crete in file number HS 5/728.

A repository of many of his letters, books, postcards and other miscellaneous writings can be found within the Patrick Leigh Fermor Archive at the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Works

[edit]Books

- The Traveller's Tree. 2001. (1950)

- The Violins of Saint-Jacques. 1977. (1953)

- A Time to Keep Silence (1957), with photographs by Joan Eyres Monsell.[40] This was an early product of the Queen Anne Press, a company managed by Leigh Fermor's friend Ian Fleming. In it he describes his experiences in several monasteries, and the profound effect the time spent there had on him.

- Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese (1958)

- Roumeli: Travels in Northern Greece (1966)

- A Time of Gifts – On Foot to Constantinople: From the Hook of Holland to the Middle Danube (1977, published by John Murray)

- Between the Woods and the Water – On Foot to Constantinople from the Hook of Holland: the Middle Danube to the Iron Gates (1986)

- Three Letters from the Andes (1991)

- Words of Mercury (2003), edited by Artemis Cooper

- In Tearing Haste: Letters Between Deborah Devonshire and Patrick Leigh Fermor (2008), edited by Charlotte Mosley. (Deborah Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, the youngest of the six Mitford sisters, was the wife of the 11th Duke of Devonshire).

- The Broken Road – Travels from Bulgaria to Mount Athos (2013), edited by Artemis Cooper and Colin Thubron from PLF's unfinished manuscript of the third volume of his account of his walk across Europe in the 1930s.[41]

- Abducting A General – The Kreipe Operation and SOE in Crete (2014)

- Dashing for the Post: the Letters of Patrick Leigh Fermor (2017), edited by Adam Sisman. Published the US as Patrick Leigh Fermor: A Life in Letters

- More Dashing: Further Letters of Patrick Leigh Fermor (2018), edited by Adam Sisman

Translations

- No Innocent Abroad (published in United States as Forever Ulysses) by C. P. Rodocanachi (1938)

- Julie de Carneilhan and Chance Acquaintances by Colette (1952)

- The Cretan Runner: His Story of the German Occupation by George Psychoundakis (1955)

Screenplays

- The Roots of Heaven (1958) adventure film, directed by John Huston

Periodicals

- "A Monastery", in The Cornhill Magazine, London, no. 979, Summer 1949.

- "From Solesmes to La Grande Trappe", in The Cornhill Magazine,[42] John Murray, London, no. 982, Spring 1950.

- "Voodoo Rites in Haiti", in World Review, London, October 1950.

- "The Rock-Monasteries of Cappadocia", in The Cornhill Magazine, London, no. 986, Spring 1951.

- "The Monasteries of the Air", in The Cornhill Magazine, London, no. 987, Summer 1951.

- "The Entrance to Hades",[43] in The Cornhill Magazine, London, no. 1011, Spring 1957.

- "Swish! Swish! Swish!",[44] originally written for the Greek edition of Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese, first appeared in The London Review of Books, London, Vol. 43, No. 15, 29 July 2021.

Forewords and introductions

- Introduction to Into Colditz by Lt Colonel Miles Reid (Michael Russell Publishing Ltd, Wilton, 1983). The story of Reid's captivity in Colditz and eventual escape by faking illness so as to qualify for repatriation. Reid had served with Leigh Fermor in Greece and was captured there trying to defend the Corinth Canal bridge in 1941.

- Foreword of Albanian Assignment by Colonel David Smiley (Chatto & Windus, London, 1984). The story of SOE in Albania, by a brother in arms of Leigh Fermor, who was later an MI6 agent.

Further reading

[edit]- Artemis Cooper: Patrick Leigh Fermor. An Adventure (2012)

- Dolores Payás: Drink Time! In the Company of Patrick Leigh Fermor (2014)

- Helias Doundoulakis, Gabriella Gafni: My Unique Lifetime Association with Patrick Leigh Fermor (2015)

- Simon Fenwick: Joan. The Remarkable Life of Joan Leigh Fermor (2017)

- Michael O'Sullivan: Patrick Leigh Fermor, Noble Encounters between Budapest and Transylvania (2018)

- John Ure (January 2015). "Fermor, Sir Patrick Michael [Paddy] Leigh (1915–2011)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/103763. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

See also

[edit]Others with or alongside the SOE in Crete:

References

[edit]- ^ Sir Max Hastings first met Leigh Fermor in his early twenties: "Across the lunch table of a London club, hearing him swapping anecdotes, in four or five languages, quite effortlessly, without showing off. I was just jaw-dropped." bbc.com.

- ^ a b c d "Patrick Leigh Fermor (obituary)". The Daily Telegraph. London. 10 June 2011.

- ^ a b c Smith, Helena "Literary legend learning to type at 92", The Guardian (2 March 2007).

- ^ Woodward, Richard B. (11 June 2011). "Patrick Leigh Fermor, Travel Writer, Dies at 96". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ His mother, who was born 26 April 1890 and died, at 54 Marine Parade, Brighton, on 22 October 1977, was the daughter of Charles Taafe Ambler (1840–1925), whose father was Warrant Officer (William) James Ambler on HMS Bellerophon, with Captain Maitland, when Napoleon surrendered. Muriel and Lewis married on 2 April 1890.

- ^ Patrick Leigh Fermor, Artemis Cooper, John Murray, 2012 page 23,

- ^ a b Cooper, Artemis (11 June 2011). "Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor: Soldier, scholar and celebrated travel writer hailed as the best of his time". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Leigh Fermor, Patrick (2005). A Time of Gifts: On Foot to Constantinople: from the Hook of Holland to the Middle Danube (Pbk ed.). New York: New York Review Books. ISBN 1-59017-165-9.

- ^ Gross, Matt (23 May 2010). "Frugal Europe, on Foot". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Alison Flood, "Patrick Leigh Fermor's final volume will be published", The Guardian (20 December 2011).

- ^ Cooper, Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure, 2012, p. 120.

- ^ Henry Hardy (December 2011). James Morwood (ed.). "Maurice Bowra on Patrick Leigh Fermor". Wadham College Gazette 2011: 106–112.

((cite journal)): Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Derek Bond, Steady, Old Man! Don't You Know There's a War On? (1990), London: Leo Cooper, ISBN 0-85052-046-0, p. 19.

- ^ "General List" The London Gazette Supplement (20 August 1940), Issue 34928, p. 5146.

- ^ Patrick Howarth, Undercover: The Men and Women of the SOE, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000; ISBN 978-1-84212-240-2.

- ^ Georgios Banasakis, "Αφιέρωμα στη μνήμη της ομάδας απαγωγής του διοικητή των Γερμανικών Δυνάμεων κατοχής (στρατηγού Κράιπε) 24-04-1944" ("Tribute to the memory of the abduction of the Governor of the German occupation (General Kraipe) 24-04-1944") (photograph) Archived 9 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine (23 September 2008).

- ^ Patrick Leigh Fermor, Abducting a General, John Murray, 2014.

- ^ Andy Walker (10 October 2014). "Patrick Leigh Fermor: Crossing Europe and kidnapping a German general". BBC News. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "To be Additional Officers of the Military Division of the said Most Excellent Order" The London Gazette (14 October 1943), Issue 36209, p. 4540.

- ^ "The Distinguished Service Order" The London Gazette (13 July 1944), Issue 36605, p. 3274.

- ^ Cooper, Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure, 2012, p. 250.

- ^ Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7195-6815-2.

- ^ Durrell, Lawrence. Bitter Lemons, pp. 103–104.

- ^ "Joan Leigh Fermor". The Independent. 10 June 2003. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Rainey-Smith, Maggie (10 June 2008). "Greece: The write stuff". NZ herald. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Maggie Rainey-Smith's tribute to Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor and her 2007 meeting". Patrick Leigh Fermor. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ Rainey-Smith, Maggie (11 June 2011). "Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor". A curious half-hour: conversations with my keyboard. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ Brevet, Brad (22 May 2013). "Before Midnight Location Map – Celine and Jesse Vacation in Greece". Rope of Silicon. Archived from the original on 1 December 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Dalrymple, William (6 September 2008). "Patrick Leigh Fermor: The man who walked". The Telegraph. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Travelling man: Biographer of a charmer" (review), The Economist (20 October 2012).

- ^ "The Man of the Mani", Radio 4 (22 June 2015).

- ^ Associated Press.

- ^ Boukalas, Pantelis (7 February 2010). "Υποθέσεις" [Hypotheses] (in Greek). Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ "Royal Society of Literature All Fellows". Royal Society of Literature. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ "Companions of Literature". Royal Society of Literature. 2 September 2023.

- ^ "Leigh Fermor, Patrick Michael", International Who's Who of Authors and Writers, 2004.

- ^ Hastings, Max. "Patrick Leigh Fermor: Profile", The Daily Telegraph, 4 January 2004.

- ^ Diplomatic Service and Overseas List The London Gazette (31 December 2003)

- ^ "The Patrick Leigh Fermor Society". Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ James Campbell, "Patrick Leigh Fermor obituary", The Guardian (10 June 2011)

- ^ Sattin, Anthony (15 September 2013). "The Broken Road – A Review". The Observer. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ edited by Peter Quennell

- ^ about the Mani

- ^ on the Mani olive harvest.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Patrick Leigh Fermor at Internet Archive

- Andy Walker, "Patrick Leigh Fermor: Crossing Europe and kidnapping a German general", BBC, 9 October 2014

- Faces of the Week: hear Leigh Fermor's voice there

- Long Distance Paths E6, E8 and E3 trace similar routes across Europe

- Official site of the documentary film The 11th Day, which contains an extensive interview with Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor, and documents the Battle of Trahili, filmed in 2003

- Profile in the New Yorker by Anthony Lane; published 22 May 2006

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Academics | |

| People | |

| Other | |