Paul Dirac | |

|---|---|

Dirac in 1933 | |

| Born | Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac 8 August 1902 Bristol, England |

| Died | 20 October 1984 (aged 82) Tallahassee, Florida, U.S. |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse |

Margit Wigner (m. 1937) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theoretical physics, mathematical physics |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Quantum Mechanics (1926) |

| Doctoral advisor | Ralph Fowler |

| Doctoral students | |

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

| Special relativity |

|---|

|

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac OM FRS[6] (/dɪˈræk/; 8 August 1902 – 20 October 1984) was an English mathematical and theoretical physicist who is considered to be one of the founders of quantum mechanics and quantum electrodynamics.[7][8] He is credited with laying the foundations of quantum field theory.[9][10][11][12] He was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, a professor of physics at Florida State University and the University of Miami, and a 1933 Nobel Prize in Physics recipient.

Dirac graduated from the University of Bristol with a first class honours Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering in 1921, and a first class honours Bachelor of Arts degree in mathematics in 1923.[13] Dirac then graduated from the University of Cambridge with a PhD in physics in 1926, writing the first ever thesis on quantum mechanics.[14]

Dirac made fundamental contributions to the early development of both quantum mechanics and quantum electrodynamics, coining the latter term.[11] Among other discoveries, he formulated the Dirac equation in 1928, which describes the behaviour of fermions and predicted the existence of antimatter,[15] which is one of the most important equations in physics,[9] and is regarded by some physicists as the "real seed of modern physics".[16] He wrote a famous paper in 1931,[17] which further predicted the existence of antimatter.[18][19][15] Dirac shared the 1933 Nobel Prize in Physics with Erwin Schrödinger for "the discovery of new productive forms of atomic theory".[20] He was the youngest ever theoretician to win the prize until T. D. Lee in 1957.[21] Dirac also contributed greatly to the reconciliation of general relativity with quantum mechanics. His 1930 monograph, The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, is one of the most influential texts on quantum mechanics.[22]

Dirac's contributions were not only restricted to quantum mechanics. He contributed to the Tube Alloys project, the British programme to research and construct atomic bombs during World War II.[23][24] Dirac made fundamental contributions to the process of uranium enrichment and the gas centrifuge,[25][26][27][24] and whose work was deemed to be "probably the most important theoretical result in centrifuge technology".[28] He also contributed to cosmology, putting forth his large numbers hypothesis.[29][30][31][32] Dirac also anticipated string theory well before its inception, with work such as the Dirac membrane and Dirac–Born–Infeld action, along with other contributions important to modern-day string and gauge theories.[33][34][35][36]

Dirac was regarded by his friends and colleagues as unusual in character. In a 1926 letter to Paul Ehrenfest, Albert Einstein wrote of a Dirac paper, "I am toiling over Dirac. This balancing on the dizzying path between genius and madness is awful." In another letter concerning the Compton effect he wrote, "I don't understand the details of Dirac at all."[37] In 1987, Abdus Salam declared that "Dirac was undoubtedly one of the greatest physicists of this or any century . . . No man except Einstein has had such a decisive influence, in so short a time, on the course of physics in this century."[38] In 1995, Stephen Hawking stated that "Dirac has done more than anyone this century, with the exception of Einstein, to advance physics and change our picture of the universe".[39] Antonino Zichichi asserted that Dirac had a greater impact on modern physics than Einstein,[16] while Stanley Deser remarked that "We all stand on Dirac's shoulders."[40] Dirac is widely considered to be on par with Sir Isaac Newton, James Clerk Maxwell, and Einstein.[41][42][43]

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac was born at his parents' home in Bristol, England, on 8 August 1902,[44] and grew up in the Bishopston area of the city.[45] His father, Charles Adrien Ladislas Dirac, was an immigrant from Saint-Maurice, Switzerland, of French descent,[6] who worked in Bristol as a French teacher. His mother, Florence Hannah Dirac, née Holten, was born to a Cornish Methodist family in Liskeard, Cornwall.[46][47] She was named after Florence Nightingale by her father, a ship's captain, who had met Nightingale while he was a soldier during the Crimean war.[48] His mother moved to Bristol as a young woman, where she worked as a librarian at the Bristol Central Library; despite this she still considered her identity to be Cornish rather than English.[49] Paul had a younger sister, Béatrice Isabelle Marguerite, known as Betty, and an older brother, Reginald Charles Félix, known as Felix,[50][51] who died by suicide in March 1925.[52] Dirac later recalled: "My parents were terribly distressed. I didn't know they cared so much ... I never knew that parents were supposed to care for their children, but from then on I knew."[53]

Charles and the children were officially Swiss nationals until they became naturalised on 22 October 1919.[54] Dirac's father was strict and authoritarian, although he disapproved of corporal punishment.[55] Dirac had a strained relationship with his father, so much so that after his father's death, Dirac wrote, "I feel much freer now, and I am my own man." Charles forced his children to speak to him only in French so that they might learn the language. When Dirac found that he could not express what he wanted to say in French, he chose to remain silent.[56][57]

Dirac was educated first at Bishop Road Primary School[58] and then at the all-boys Merchant Venturers' Technical College (later Cotham School), where his father was a French teacher.[59] The school was an institution attached to the University of Bristol, which shared grounds and staff.[60] It emphasised technical subjects like bricklaying, shoemaking and metalwork, and modern languages.[61] This was unusual at a time when secondary education in Britain was still dedicated largely to the classics, and something for which Dirac would later express his gratitude.[60]

Dirac studied electrical engineering on a City of Bristol University Scholarship at the University of Bristol's engineering faculty, which was co-located with the Merchant Venturers' Technical College.[62] Shortly before he completed his degree in 1921, he sat for the entrance examination for St John's College, Cambridge. He passed and was awarded a £70 scholarship, but this fell short of the amount of money required to live and study at Cambridge. Despite having graduated with a first class honours Bachelor of Science degree in electrical engineering, the economic climate of the post-war depression was such that he was unable to find work as an engineer. Instead, he took up an offer to study for a Bachelor of Arts degree in mathematics at the University of Bristol free of charge. He was permitted to skip the first year of the course owing to his engineering degree.[63] Under the influence of Peter Fraser, whom Dirac called the best mathematics teacher, he had the most interest in projective geometry, and began applying it to the geometrical version of relativity Minkowski developed.[64]

In 1923, Dirac graduated, once again with first class honours, and received a £140 scholarship from the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research.[65] Along with his £70 scholarship from St John's College, this was enough to live at Cambridge. There, Dirac pursued his interests in the theory of general relativity, an interest he had gained earlier as a student in Bristol, and in the nascent field of quantum physics, under the supervision of Ralph Fowler.[66] From 1925 to 1928 he held an 1851 Research Fellowship from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851.[67] He completed his PhD in June 1926 with the first thesis on quantum mechanics to be submitted anywhere.[68] He then continued his research in Copenhagen and Göttingen.[67] In the spring of 1929, he was a visiting professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[69][70]

In 1937, Dirac married[71] Margit Wigner, a sister of physicist Eugene Wigner[72] and a divorcee.[73] Dirac raised Margit's two children, Judith and Gabriel, as if they were his own.[74] Paul and Margit Dirac also had two daughters together, Mary Elizabeth and Florence Monica.[75]

Margit, known as Manci, had visited her brother in 1934 in Princeton, New Jersey, from their native Hungary and, while at dinner at the Annex Restaurant, met the "lonely-looking man at the next table". This account from a Korean physicist, Y. S. Kim, who met and was influenced by Dirac, also says: "It is quite fortunate for the physics community that Manci took good care of our respected Paul A. M. Dirac. Dirac published eleven papers during the period 1939–46. Dirac was able to maintain his normal research productivity only because Manci was in charge of everything else".[76]

Dirac was known among his colleagues for his precise and taciturn nature. His colleagues in Cambridge jokingly defined a unit called a "dirac", which was one word per hour.[77] When Niels Bohr complained that he did not know how to finish a sentence in a scientific article he was writing, Dirac replied, "I was taught at school never to start a sentence without knowing the end of it."[78] He criticised the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer's interest in poetry: "The aim of science is to make difficult things understandable in a simpler way; the aim of poetry is to state simple things in an incomprehensible way. The two are incompatible."[79]

Dirac himself wrote in his diary during his postgraduate years that he concentrated solely on his research, and stopped only on Sunday when he took long strolls alone.[80]

An anecdote recounted in a review of the 2009 biography tells of Werner Heisenberg and Dirac sailing on an ocean liner to a conference in Japan in August 1929. "Both still in their twenties, and unmarried, they made an odd couple. Heisenberg was a ladies' man who constantly flirted and danced, while Dirac—'an Edwardian geek', as biographer Graham Farmelo puts it—suffered agonies if forced into any kind of socializing or small talk. 'Why do you dance?' Dirac asked his companion. 'When there are nice girls, it is a pleasure,' Heisenberg replied. Dirac pondered this notion, then blurted out: 'But, Heisenberg, how do you know beforehand that the girls are nice?'"[81]

Margit Dirac told both George Gamow and Anton Capri in the 1960s that her husband had said to a house visitor, "Allow me to present Wigner's sister, who is now my wife."[82][83]

Another story told of Dirac is that when he first met the young Richard Feynman at a conference, he said after a long silence, "I have an equation. Do you have one too?"[84]

After he presented a lecture at a conference, one colleague raised his hand and said: "I don't understand the equation on the top-right-hand corner of the blackboard". After a long silence, the moderator asked Dirac if he wanted to answer the question, to which Dirac replied: "That was not a question, it was a comment."[85][86]

Dirac was also noted for his personal modesty. He called the equation for the time evolution of a quantum-mechanical operator, which he was the first to write down, the "Heisenberg equation of motion". Most physicists speak of Fermi–Dirac statistics for half-integer-spin particles and Bose–Einstein statistics for integer-spin particles. While lecturing later in life, Dirac always insisted on calling the former "Fermi statistics". He referred to the latter as "Bose statistics" for reasons, he explained, of "symmetry".[87]

Heisenberg recollected a conversation among young participants at the 1927 Solvay Conference about Einstein and Planck's views on religion between Wolfgang Pauli, Heisenberg and Dirac. Dirac's contribution was a criticism of the political purpose of religion, which Bohr regarded as quite lucid when hearing it from Heisenberg later.[88] Among other things, Heisenberg imagined that Dirac might say:

I don't know why we are discussing religion. If we are honest—and scientists have to be—we must admit that religion is a jumble of false assertions, with no basis in reality. The very idea of God is a product of the human imagination. It is quite understandable why primitive people, who were so much more exposed to the overpowering forces of nature than we are today, should have personified these forces in fear and trembling. But nowadays, when we understand so many natural processes, we have no need for such solutions. I can't for the life of me see how the postulate of an Almighty God helps us in any way. What I do see is that this assumption leads to such unproductive questions as to why God allows so much misery and injustice, the exploitation of the poor by the rich, and all the other horrors He might have prevented. If religion is still being taught, it is by no means because its ideas still convince us, but simply because some of us want to keep the lower classes quiet. Quiet people are much easier to govern than clamorous and dissatisfied ones. They are also much easier to exploit. Religion is a kind of opium that allows a nation to lull itself into wishful dreams and so forget the injustices that are being perpetrated against the people. Hence the close alliance between those two great political forces, the State and the Church. Both need the illusion that a kindly God rewards—in heaven if not on earth—all those who have not risen up against injustice, who have done their duty quietly and uncomplainingly. That is precisely why the honest assertion that God is a mere product of the human imagination is branded as the worst of all mortal sins.[89]

Heisenberg's view was tolerant. Pauli, raised as a Catholic, had kept silent after some initial remarks, but when finally he was asked for his opinion, said: "Well, our friend Dirac has got a religion and its guiding principle is 'There is no God, and Paul Dirac is His prophet.'" Everybody, including Dirac, burst into laughter.[90][91]

Later in life, Dirac wrote an article mentioning God that appeared in the May 1963 edition of Scientific American, Dirac wrote:

It seems to be one of the fundamental features of nature that fundamental physical laws are described in terms of a mathematical theory of great beauty and power, needing quite a high standard of mathematics for one to understand it. You may wonder: Why is nature constructed along these lines? One can only answer that our present knowledge seems to show that nature is so constructed. We simply have to accept it. One could perhaps describe the situation by saying that God is a mathematician of a very high order, and He used very advanced mathematics in constructing the universe. Our feeble attempts at mathematics enable us to understand a bit of the universe, and as we proceed to develop higher and higher mathematics we can hope to understand the universe better.[92]

In 1971, at a conference meeting, Dirac expressed his views on the existence of God.[93] Dirac explained that the existence of God could be justified only if an improbable event were to have taken place in the past:

It could be that it is extremely difficult to start life. It might be that it is so difficult to start a life that it has happened only once among all the planets... Let us consider, just as a conjecture, that the chance of life starting when we have got suitable physical conditions is 10−100. I don't have any logical reason for proposing this figure, I just want you to consider it as a possibility. Under those conditions ... it is almost certain that life would not have started. And I feel that under those conditions it will be necessary to assume the existence of a god to start off life. I would like, therefore, to set up this connection between the existence of a god and the physical laws: if physical laws are such that to start off life involves an excessively small chance so that it will not be reasonable to suppose that life would have started just by blind chance, then there must be a god, and such a god would probably be showing his influence in the quantum jumps which are taking place later on. On the other hand, if life can start very easily and does not need any divine influence, then I will say that there is no god.[94]

Dirac did not commit himself to any definite view, but he described the possibilities for scientifically answering the question of God.[94]

Dirac established the most general theory of quantum mechanics and discovered the relativistic equation for the electron, which now bears his name. The remarkable notion of an antiparticle to each fermion particle – e.g. the positron as antiparticle to the electron – stems from his equation. He was the first to develop quantum field theory, which underlies all theoretical work on sub-atomic or "elementary" particles today, work that is fundamental to our understanding of the forces of nature. He proposed and investigated the concept of a magnetic monopole, an object not yet known empirically, as a means of bringing even greater symmetry to James Clerk Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism. He is credited as being the one to create quantum field theory, alongside creating quantum electrodynamics and coining the term.[10][12] Dirac also coined the terms "fermion" and "boson".[95]

Throughout his career, Dirac was motivated by the principles of mathematical beauty,[96] with Peter Goddard stating that "Dirac cited mathematical beauty as the ultimate criterion for selecting the way forward in theoretical physics".[97] Dirac was recognised for being mathematically gifted, as during his time in university, academics had affirmed that Dirac had an "ability of the highest order in mathematical physics",[98] with Ebenezer Cunningham stating that Dirac was "quite the most original student I have met in the subject of mathematical physics".[99] Therefore, Dirac was known for his "astounding physical intuition combined with the ability to invent new mathematics to create new physics".[18] During his career, Dirac made numerous important contributions to mathematical subjects, including the Dirac delta function, Dirac algebra and the Dirac operator.

Dirac's first step into a new quantum theory was taken late in September 1925. Ralph Fowler, his research supervisor, had received a proof copy of an exploratory paper by Werner Heisenberg in the framework of the old quantum theory of Bohr and Sommerfeld. Heisenberg leaned heavily on Bohr's correspondence principle but changed the equations so that they involved directly observable quantities, leading to the matrix formulation of quantum mechanics. Fowler sent Heisenberg's paper on to Dirac, who was on vacation in Bristol, asking him to look into this paper carefully.[100]

Dirac's attention was drawn to a mysterious mathematical relationship, at first sight unintelligible, that Heisenberg had established. Several weeks later, back in Cambridge, Dirac suddenly recognised that this mathematical form had the same structure as the Poisson brackets that occur in the classical dynamics of particle motion.[100] At the time, his memory of Poisson brackets was rather vague, but he found E. T. Whittaker's Analytical Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies illuminating.[101] From his new understanding, he developed a quantum theory based on non-commuting dynamical variables. This led him to the most profound and significant general formulation of quantum mechanics to date.[102] His novel formulation using Dirac brackets allowed him to obtain the quantisation rules in a novel and more illuminating manner. For this work,[103] published in 1926, Dirac received a PhD from Cambridge. This formed the basis for Fermi–Dirac statistics that applies to systems consisting of many identical spin 1/2 particles (i.e. that obey the Pauli exclusion principle), e.g. electrons in solids and liquids, and importantly to the field of conduction in semi-conductors.

Dirac was famously not bothered by issues of interpretation in quantum theory. In fact, in a paper published in a book in his honour, he wrote: "The interpretation of quantum mechanics has been dealt with by many authors, and I do not want to discuss it here. I want to deal with more fundamental things."[104] However, in 1964 he wrote a short article about the interpretation of quantum field theory when based on the Heisenberg picture of quantum theory; his primary point in the article was that the Schrodinger model does not work for this purpose.[105]

|

Further information: Dirac equation |

In 1928, building on 2×2 spin matrices which he purported to have discovered independently of Wolfgang Pauli's work on non-relativistic spin systems (Dirac told Abraham Pais, "I believe I got these [matrices] independently of Pauli and possibly Pauli got these independently of me."),[106] he proposed the Dirac equation as a relativistic equation of motion for the wave function of the electron.[107] This work led Dirac to predict the existence of the positron, the electron's antiparticle, which he interpreted in terms of what came to be called the Dirac sea.[108] The positron was observed by Carl Anderson in 1932. Dirac's equation also contributed to explaining the origin of quantum spin as a relativistic phenomenon.

The necessity of fermions (matter) being created and destroyed in Enrico Fermi's 1934 theory of beta decay led to a reinterpretation of Dirac's equation as a "classical" field equation for any point particle of spin ħ/2, itself subject to quantisation conditions involving anti-commutators. Thus reinterpreted, in 1934 by Werner Heisenberg, as a (quantum) field equation accurately describing all elementary matter particles – today quarks and leptons – this Dirac field equation is as central to theoretical physics as the Maxwell, Yang–Mills and Einstein field equations. Dirac is regarded as the founder of quantum electrodynamics, being the first to use that term. He also introduced the idea of vacuum polarisation in the early 1930s. This work was key to the development of quantum mechanics by the next generation of theorists, in particular Schwinger, Feynman, Sin-Itiro Tomonaga and Dyson in their formulation of quantum electrodynamics.

Dirac's The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, published in 1930, is a landmark in the history of science. It quickly became one of the standard textbooks on the subject and is still used today. In that book, Dirac incorporated the previous work of Werner Heisenberg on matrix mechanics and of Erwin Schrödinger on wave mechanics into a single mathematical formalism that associates measurable quantities to operators acting on the Hilbert space of vectors that describe the state of a physical system. The book also introduced the Dirac delta function. Following his 1939 article,[109] he also included the bra–ket notation in the third edition of his book,[110] thereby contributing to its universal use nowadays.

In 1931, Dirac proposed that the existence of a single magnetic monopole in the universe would suffice to explain the quantisation of electrical charge.[111] No such monopole has been detected, despite numerous attempts and preliminary claims.[112] (see also Searches for magnetic monopoles).

Dirac quantised the gravitational field.[46][113] His work laid the foundations for canonical quantum gravity.[114] In his 1959 lecture at the Lindau Meetings, Dirac discussed why gravitational waves have "physical significance".[115] Dirac predicted gravitational waves would have well defined energy density in 1964.[113] Dirac reintroduced the term "graviton" in a number of lectures in 1959, noting that the energy of the gravitational field should come in quanta.[116][117]

Dirac is seen as having anticipated string theory, with his work on the Dirac membrane and Dirac–Born–Infeld action, both of which he proposed in a 1962 paper,[118][119] along with other contributions.[33][34] He also developed a general theory of the quantum field with dynamical constraints,[120][121][33] which forms the basis of the gauge theories and superstring theories of today.[33][46][122]

Shortly after Wolfgang Pauli proposed his Pauli exclusion principle that two electrons cannot occupy the same quantum energy level, Enrico Fermi and Dirac[103] both realized the principle would dramatically alter the statistical mechanics of electron systems. This work became the basis for Fermi-Dirac statistics.[123]: 488

Dirac wrote an influential paper in 1933 regarding the Lagrangian in quantum mechanics.[124] The paper served as the basis for Julian Schwinger and his quantum action principle,[125] and laid the foundations for Richard Feynman's development of a completely new approach to quantum mechanics, the path integral formulation.[113][126]

In a 1963 paper,[127] Dirac initiated the study of field theory on anti-de Sitter space (AdS).[128] The paper contains the mathematics of combining special relativity with the quantum mechanics of quarks inside hadrons, and lays the foundations of two-mode squeezed states that are essential to modern quantum optics, though Dirac did not realize it at the time.[129] Dirac previously worked on AdS during the 1930s,[130] publishing a paper in 1935.[131]

In 1930, Victor Weisskopf and Eugene Wigner published their famous and now standard calculation of spontaneous radiation emission in atomic and molecular physics.[132] Remarkably, in a letter to Niels Bohr in February of 1927, Dirac had come to the same calculation,[133] but he did not publish it.[134]

In 1938,[135] Dirac renormalized the mass in the theory of Abraham-Lorentz electron, leading to the Abraham–Lorentz–Dirac force, which is the relativistic-classical electron model; however, this model has solutions that suggest force increase exponentially with time.[136]

Fermi's golden rule, the formula for computing quantum transitions in time dependent systems, declared a "golden rule" by Enrico Fermi, was derived by Dirac.[137] Dirac was the one to initiate the development of time-dependent perturbation theory in his early work on semi-classical atoms interacting with an electromagnetic field. Dirac, with Werner Heisenberg, John Archibald Wheeler, Richard Feynman, and Freeman Dyson ultimately developed this concept into an invaluable tool for modern physics, used in the calculation of the properties of any physical system and a wide array of phenomena.[138]

Dirac was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge from 1932 to 1969. He conceived the Helikon vortex isotope separation process in 1934.[139][140] In 1937, he proposed a speculative cosmological model based on the large numbers hypothesis. During World War II, he conducted important theoretical work on uranium enrichment by gas centrifuge.[141] He introduced the separative work unit (SWU) in 1941.[142] He contributed to the Tube Alloys project, the British programme to research and construct atomic bombs during World War II.[143][24]

Dirac's quantum electrodynamics (QED) made predictions that were – more often than not – infinite and therefore unacceptable. A workaround known as renormalisation was developed, but Dirac never accepted this. "I must say that I am very dissatisfied with the situation", he said in 1975, "because this so-called 'good theory' does involve neglecting infinities which appear in its equations, neglecting them in an arbitrary way. This is just not sensible mathematics. Sensible mathematics involves neglecting a quantity when it is small – not neglecting it just because it is infinitely great and you do not want it!"[144] His refusal to accept renormalisation resulted in his work on the subject moving increasingly out of the mainstream.

However, from his once rejected notes he managed to work on putting quantum electrodynamics on "logical foundations" based on Hamiltonian formalism that he formulated. He found a rather novel way of deriving the anomalous magnetic moment "Schwinger term" and also the Lamb shift, afresh in 1963, using the Heisenberg picture and without using the joining method used by Weisskopf and French, and by the two pioneers of modern QED, Schwinger and Feynman. That was two years before the Tomonaga–Schwinger–Feynman QED was given formal recognition by an award of the Nobel Prize for physics.

Weisskopf and French (FW) were the first to obtain the correct result for the Lamb shift and the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron. At first FW results did not agree with the incorrect but independent results of Feynman and Schwinger.[145] The 1963–1964 lectures Dirac gave on quantum field theory at Yeshiva University were published in 1966 as the Belfer Graduate School of Science, Monograph Series Number, 3.

After having relocated to Florida to be near his elder daughter, Mary, Dirac spent his last fourteen years of both life and physics research at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida, and Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida.

In the 1950s in his search for a better QED, Paul Dirac developed the Hamiltonian theory of constraints[146] based on lectures that he delivered at the 1949 International Mathematical Congress in Canada. Dirac[147] had also solved the problem of putting the Schwinger–Tomonaga equation into the Schrödinger representation[148] and given explicit expressions for the scalar meson field (spin zero pion or pseudoscalar meson), the vector meson field (spin one rho meson), and the electromagnetic field (spin one massless boson, photon).

The Hamiltonian of constrained systems is one of Dirac's many masterpieces. It is a powerful generalisation of Hamiltonian theory that remains valid for curved spacetime. The equations for the Hamiltonian involve only six degrees of freedom described by , for each point of the surface on which the state is considered. The (m = 0, 1, 2, 3) appear in the theory only through the variables , which occur as arbitrary coefficients in the equations of motion. There are four constraints or weak equations for each point of the surface = constant. Three of them form the four vector density in the surface. The fourth is a 3-dimensional scalar density in the surface HL ≈ 0; Hr ≈ 0 (r = 1, 2, 3)

In the late 1950s, he applied the Hamiltonian methods he had developed to cast Einstein's general relativity in Hamiltonian form[149][150] and to bring to a technical completion the quantisation problem of gravitation and bring it also closer to the rest of physics according to Salam and DeWitt. In 1959 he also gave an invited talk on "Energy of the Gravitational Field" at the New York Meeting of the American Physical Society.[151] In 1964 he published his Lectures on Quantum Mechanics (London: Academic) which deals with constrained dynamics of nonlinear dynamical systems including quantisation of curved spacetime. He also published a paper entitled "Quantization of the Gravitational Field" in the 1967 ICTP/IAEA Trieste Symposium on Contemporary Physics.

From September 1970 to January 1971, Dirac was a visiting professor at Florida State University in Tallahassee. During that time he was offered a permanent position there, which he accepted, becoming a full professor in 1972. Contemporary accounts of his time there describe it as happy except that he apparently found the summer heat oppressive and liked to escape from it to Cambridge.[152]

He would walk about a mile to work each day and was fond of swimming in one of the two nearby lakes (Silver Lake and Lost Lake), and was also more sociable than he had been at the University of Cambridge, where he mostly worked at home apart from giving classes and seminars. At Florida State, he would usually eat lunch with his colleagues before taking a nap.[153]

Dirac published over 60 papers in those last twelve years of his life, including a short book on general relativity.[154] His last paper (1984), entitled "The inadequacies of quantum field theory," contains his final judgment on quantum field theory: "These rules of renormalisation give surprisingly, excessively good agreement with experiments. Most physicists say that these working rules are, therefore, correct. I feel that is not an adequate reason. Just because the results happen to be in agreement with observation does not prove that one's theory is correct." The paper ends with the words: "I have spent many years searching for a Hamiltonian to bring into the theory and have not yet found it. I shall continue to work on it as long as I can and other people, I hope, will follow along such lines."[155]

Amongst his many students[3][156] were Homi J. Bhabha,[1] Fred Hoyle, John Polkinghorne[5] and Freeman Dyson.[157] Polkinghorne recalls that Dirac "was once asked what was his fundamental belief. He strode to a blackboard and wrote that the laws of nature should be expressed in beautiful equations."[158]

Dirac shared the 1933 Nobel Prize for physics with Erwin Schrödinger "for the discovery of new productive forms of atomic theory".[20] Dirac was also awarded the Royal Medal in 1939 and both the Copley Medal and the Max Planck Medal in 1952. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1930,[159][6] a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1938,[160] an Honorary Fellow of the American Physical Society in 1948, a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1949,[161] a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1950,[162] and an Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Physics, London in 1971. He received the inaugural J. Robert Oppenheimer Memorial Prize in 1969.[163][164] Dirac became a member of the Order of Merit in 1973, having previously turned down a knighthood as he did not want to be addressed by his first name.[81][165]

In 1984, Dirac died in Tallahassee, Florida, and was buried at Tallahassee's Roselawn Cemetery.[166] Dirac's childhood home in Bishopston, Bristol is commemorated with a blue plaque,[167] and the nearby Dirac Road is named in recognition of his links with the city of Bristol. A commemorative stone was erected in a garden in Saint-Maurice, Switzerland, the town of origin of his father's family, on 1 August 1991. On 13 November 1995 a commemorative marker, made from Burlington green slate and inscribed with the Dirac equation, was unveiled in Westminster Abbey.[166][168] The Dean of Westminster, Edward Carpenter, had initially refused permission for the memorial, thinking Dirac to be anti-Christian, but was eventually (over a five-year period) persuaded to relent.[169]

The influence and importance of Dirac's work have increased with the decades, and physicists use daily the concepts and equations that he developed.

In 1975, Dirac gave a series of five lectures at the University of New South Wales which were subsequently published as a book, Directions in Physics (1978). He donated the royalties from this book to the university for the establishment of Dirac Lecture Series. The Silver Dirac Medal for the Advancement of Theoretical Physics is awarded by the University of New South Wales to commemorate the lecture.[170]

Immediately after his death, two organisations of professional physicists established annual awards in Dirac's memory. The Institute of Physics, the United Kingdom's professional body for physicists, awards the Paul Dirac Medal for "outstanding contributions to theoretical (including mathematical and computational) physics".[171] The first three recipients were Stephen Hawking (1987), John Stewart Bell (1988), and Roger Penrose (1989). Since 1985, the International Centre for Theoretical Physics awards the Dirac Medal of the ICTP each year on Dirac's birthday (8 August).[172]

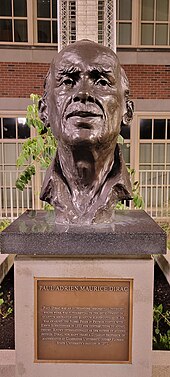

The Dirac-Hellman Award at Florida State University was endowed by Bruce P. Hellman in 1997 to reward outstanding work in theoretical physics by FSU researchers.[173] The Paul A.M. Dirac Science Library at Florida State University, which Manci opened in December 1989,[174] is named in his honour, and his papers are held there.[175] Outside is a statue of him by Gabriella Bollobás.[176] The street on which the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory in Innovation Park of Tallahassee, Florida, is located is named Paul Dirac Drive. As well as in his hometown of Bristol, there is also a road named after him, Dirac Place, in Didcot, Oxfordshire.[177] The Dirac-Higgs Science Centre in Bristol is also named in his honour.[178]

The BBC named a video codec, Dirac, in his honour. An asteroid discovered in 1983 was named after Dirac.[179] The Distributed Research utilising Advanced Computing (DiRAC) and Dirac software are named in his honour.