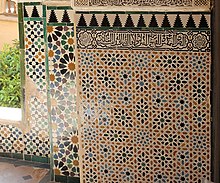

Zellij (Arabic: الزليج, romanized: zillīj; also spelled zillij or zellige) is a style of mosaic tilework made from individually hand-chiseled tile pieces.[1]: 335 [2]: 41 [3]: 166 The pieces were typically of different colours and fitted together to form various patterns on the basis of tessellations, most notably elaborate Islamic geometric motifs such as radiating star patterns composed of various polygons.[1][4][5][6] This form of Islamic art is one of the main characteristics of architecture in the western Islamic world. It is found in the architecture of Morocco, the architecture of Algeria, early Islamic sites in Tunisia, and in the historic monuments of al-Andalus (in the Iberian Peninsula). From the 14th century onwards, zellij became a standard decorative element along lower walls, in fountains and pools, on minarets, and for the paving of floors.[1][5]

After the 15th century the traditional mosaic zellij fell out of fashion in most countries except for Morocco, where it continues to be produced today.[1]: 414–415 Zellij is found in modern buildings making use of traditional designs such as the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca which adds a new color palette with traditional designs.[7] The influence of zellij patterns was also evident in Spanish tiles produced during the Renaissance period and is seen in some modern imitations painted on square tiles.[8]: 102 [2]: 41

The word zillīj (زليج) is derived from the verb zalaja (زَلَجَ) meaning "to slide,"[9] in reference to the smooth, glazed surface of the tiles. The word azulejo in Portuguese and Spanish, referring to a style of painted tile in Portugal and Spain, derives from the word zillīj.[10][11] In Spain, the mosaic tile technique used in historical Islamic monuments like the Alhambra is also referred to as alicatado, a Spanish word deriving from the Arabic verb qata'a (ﻗَﻄَﻊَ) meaning "to cut".[12][3]: 166

Zellij fragments from al-Mansuriyya (Sabra) in Tunisia, possibly dating from either the mid-10th century Fatimid foundation or from the mid-11th Zirid occupation, suggest that the technique may have developed in the western Islamic world around this period.[5] Georges Marçais argued that these fragments, along with similar decoration found at Mahdia, indicate that the technique likely originated in Ifriqiya and was subsequently exported further west.[1]: 99, 335 It was probably inspired or derived from Byzantine mosaics and then adapted by Muslim craftsmen for faience tiles.[4][6]: 28 By the 11th century, the zellij technique had reached a sophisticated level in the western Islamic world, as attested in the elaborate pavements found at Qal'at Bani Hammad in Algeria.[5]

During the Almohad period, prominent bands of ceramic decoration in green and white were already features on the minarets of the Kutubiyya Mosque and the Kasbah Mosque of Marrakesh. Relatively simple in design, they may have reflected artistic influences from Sanhaja Berber culture.[1]: 231 Jonathan Bloom cites the glazed tiles on the minaret of the Kutubiyya Mosque, dating from the mid-12th century, as the earliest reliably-dated example of zellij in Morocco.[13]: 26 The individual tile pieces are large, allowing the pattern to be visible from afar. Each piece was pierced with a small hole prior to being baked so that the tiles could be affixed by nails to a wooden frame set into a mortar surface on this part of the minaret.[14]: 329 The minaret of the Kasbah Mosque, built slightly later in the 1190s, makes greater use of ceramic decoration generally, including geometric mosaics on the upper parts of the minaret in the same technique as those of the Kutubiyya (though slightly more varied in design).[a] The tiles on both minarets today are modern reproductions of the originals, of which fragments have been preserved in the reserve collection of the Badi Palace museum.[14]: 326–333

The more complex zellij style that we know today became widespread during the first half of the 14th century under the Marinid, Zayyanid, and Nasrid dynastic periods in Morocco, Algeria, and al-Andalus.[1]: 335–336 [15] Due to the significant cultural unity and relations between al-Andalus and the western Maghreb, the forms of zellij under Marinid, Nasrid, and Zayyanid patronage are extremely similar.[3]: 188–189 In Ifriqiya (Tunisia), under the Hafsid dynasty, zellij tiling largely fell out of style during this same period and was replaced by a preference for stone and marble paneling.[1]: 486–487

Zellij tiling was most typically used to pave floors and to cover the lower walls inside buildings. Zellij was also used on the exterior of minarets and on some entrance portals.[5] Geometric motifs predominated, with patterns of increasing complexity being formed during this period. Less frequently, vegetal or floral arabesque motifs were also created. On walls, zellij geometric dadoes were commonly topped by an epigraphic frieze.[5] By this period, more colours were employed such as yellow (using iron oxides or chrome yellow), blues, and a dark brown manganese colour.[1]: 336 This style of tile mosaic, formed by assembling a large number of small hand-cut pieces to form a pattern, is evident in famous buildings of the period such as the Alhambra palaces of the Nasrids, the mosques of Tlemcen, and the Marinid madrasas of Fez, Meknes, and Salé. It is also found in some Christian Spanish palaces of the same period who employed Muslim or Mudéjar craftsmen, most notably the Alcazar of Seville, whose 14th-century sections are contemporary with the Alhambra and contain zellij tilework in the same style, although of slightly lesser sophistication.[16]: 63–64 [3]: 172

Among the most exceptional surviving examples of Nasrid zellij art are the dadoes of the Mirador de Lindaraja and the Torre de la Cautiva in the Alhambra, both from the 14th century. Whereas Arabic epigraphy was usually carved in stucco or painted on larger square tiles, these two examples contain very fine Arabic inscriptions in Naskhi script that are made from the assembly of coloured tile pieces cut in the form of the letters themselves and set into a white background.[17] The tiles of the Torre de la Cautiva are further distinguished by the use of a purple colour which is unique in architectural zellij decoration.[17] The dado of the Mirador of Lindaraja also contains a particularly advanced geometric composition with very fine mosaic pieces below the level of the inscription.[18] Some of the tile pieces in this composition measure as little as 2 millimeters in width.[6]: 129

In addition to zellij work further west, a somewhat distinctive style of zellij with brightly coloured pieces, often in floral patterns of palmettes and scrollwork, developed among the craftsmen of Tlemcen. The most important early example of this style was the decoration of the Tashfiniya Madrasa (no longer extant), founded by Abu Tashfin I (r. 1318–1337). This type subsequently appeared in later monuments of this era, mainly in Tlemcen (such as the Mosque and madrasa of Abu Madyan) but also further afield in the Marinid madrasa of Chellah, suggesting that the same workshop of craftsmen may have been employed by the Marinids around this time.[3]: 187, 195, 206 [14]: 526 [19] The use of zellij decoration on entrance portals, otherwise not common in the rest of the Maghreb, was also most characteristic of the architecture of Tlemcen.[19]: 178 Today, the archaeological museum of Tlemcen contains many remains of panels and fragments of zellij from various medieval monuments dating back to the Zayyanid dynasty.[20]

The epigraphic friezes in Marinid tilework, which typically topped the main mosaic dadoes, were made through a different technique known more widely as sgraffito (from the Italian word for "scratched"[21]).[16]: 67 [5] In this technique, square panels were glazed in a black colour and the glaze was then chipped away around the desired motif, leaving the Arabic inscription and other decorative flourishes in black relief against a bare earth ground.[22]: 138 [23]: 74 [1]: 336 [16]: 67 Occasionally the earth background is covered with a white coating, and on some occasions a green glaze is used instead of black in order to leave a green motif in relief. An example of the latter is seen on the ceramic decoration of the minaret of the Bou Inania Madrasa in Fez (1350–1355), within the sunken spaces of the sebka motif.[1]: 336

In the 16th century most of North Africa came under Ottoman rule. In Algeria, the indigenous zellij style was mostly supplanted by small square tiles imported from Europe – especially from Italy, Spain, and Delft – and sometimes from Tunis. Some examples of more traditional mosaic tiles found in this late period may have continued to be produced in Tlemcen.[1]: 449 In Tunisia, another style of tile decoration, Qallaline tiles, became common during the 18th century and was produced locally. It consisted of square panels of fixed size, painted with scenes and flowers, in a technique similar to Italian maiolica rather than to the earlier mosaic technique.[1]: 487 [5][16]: 84–86

In Spain, where former Muslim-controlled territories had come under Christian rule, new techniques of tilemaking developed. As wealthy Spaniards favoured the Mudéjar style to decorate their residences, the demand for mosaic tilework in this style increased beyond what tilemakers could produce, requiring them to consider new methods.[8]: 102 Towards the late 15th and early 16th centuries Seville became an important production center for a type of tile known as cuenca ("hollow") or arista ("ridge"). In this technique, motifs were formed by pressing a metal or wooden mould over the unbaked tile, leaving a motif delineated by thin ridges of clay that prevented the different colours in between from bleeding into each other during baking. This was similar to the older cuerda seca technique but more efficient for mass production.[16]: 64–65 [8]: 102 [25] The motifs on these tiles imitated earlier Islamic and Mudéjar designs from the zellij mosaic tradition or blended them with contemporary European influences such as Gothic or Italian Renaissance.[8]: 102 [16]: 64–65 [26] Fine examples of these tiles can be found in the early 16th-century decoration of the Casa de Pilatos in Seville.[16]: 65 This type of tile was produced well into the 17th century and was widely exported from Spain to other European countries and to the Spanish colonies in the Americas.[8]: 102

In Morocco, existing architectural styles were perpetuated with relatively few outside influences.[3]: 243 Here, traditional zellij continued to be used after the 15th century and continues to be produced up to the present day.[1]: 414–415 Under the Saadi dynasty in the 16th century and in subsequent centuries, the usage of zellij became even more ubiquitous within Morocco and covered more and more surfaces.[1]: 415 During the reign of the 'Alawi sultan Moulay Isma'il (1672–1727), zellij was used extensively on the facades of the monumental gates of the new imperial citadel in Meknes.[16]: 78

Under the Saadis, the complexity of geometric patterns was increased for the decoration of the most luxurious buildings, such as the Badi Palace (now ruined).[27]: 268 Some of the zellij compositions in the Saadian Tombs are among the best examples of this type in situ.[27]: 194–200 [1]: 415 In this example, craftsmen employed finer (thinner) mosaic pieces and the thin, linear pieces that form the strapwork are coloured whereas the larger pieces that form the "background" are white. This scheme reversed the colouring pattern generally seen in older zellij (where the ground was coloured and the linear strapwork was white).[1]: 415

Over the centuries since the Saadi period, the sgraffito technique previously used for Marinid epigraphic friezes came into more general usage in Morocco as a simpler and more economic alternative to mosaics. This type of tile was often employed on the spandrels of large gateways and portals. The motifs are often relatively simpler and less colourful than the traditional mosaic zellij style.[1]: 415 In addition to black glaze, green or blue glaze was also used in later examples of this type to obtain motifs in these colours. An example of this can be seen on the blue and green tiled façades of the Bab Bou Jeloud gate in Fez, built in 1913.[22]: 138

In later centuries, the interlacing strapwork that once separated the polygons in geometric mosaics was no longer standard and Moroccan craftsmen created rosette-style geometric compositions on an increasingly large scale.[22]: 152 [1]: 415 The culmination of this latter style is visible in the palaces built during the 19th and 20th centuries. New colours were also introduced into the palette during this period, including red, a bright yellow, and dark blue.[22]: 152 Zellij was employed on a wider array of architectural elements. The geometric rosette motifs were used to decorate fountains (or the ground around a fountain), the spandrels of arched doorways, or wall surfaces framed by arches of carved stucco. Simpler checkerboard-like motifs were used as backgrounds for the rosette compositions or to cover other large surfaces. In more modern houses and mansions, even cylindrical pillars were covered in tilework up to the level of the capital.[1]: 415

In Morocco today, zellij art form remains one of the hallmarks of Moroccan cultural and artistic identity[29] and continues to be used in modern Moroccan architecture.[2]: 41 Fez remains its most important center of production.[29][30] Workshops in other cities like Meknes, Salé and Marrakesh generally emulate the same style as the craftsmanship of Fez.[30] The exception to this is the city of Tétouan (in northern Morocco), which since the 19th century has hosted its own mosaic zellij industry employing a technique differing from that of Fez.[30] The patterns of traditional zellij are also still used in some Spanish decorative tiles, but in modern Spanish tiles the geometric motifs are simply painted and baked on large tiles rather than formed by mosaic.[2]: 41

Zellij tiles are first fabricated in glazed squares, typically 10 cm per side, then cut by hand with a small adze-like hammer into a variety of pre-established shapes (usually memorized by rote learning) necessary to form the overall pattern.[2]: 41 [1]: 414 Although the exact patterns vary from case to case, the underlying principles have been constant for centuries and Moroccan craftsmen are still adept at making them today.[2]: 41–43 The small shapes (cut according to a precise radius gauge) of different colours are then assembled in a geometrical structure as in a puzzle to form the completed mosaic. Uniquely in the city of Tétouan, zellij tiles are cut into the desired shapes before being baked. This results in a harder enamel that lasts longer, but the colours are not as bright and the tile pieces generally do not fit together as tightly as those produced in other cities like Fez.[1]: 414–415 [2]: 41

Once baked and cut, the tiles were laid face down on the ground and assembled together into the intended pattern. The back of the tile pieces were coated together with thin layers of plaster or whitewash. Once dry, this coating bonded the tile pieces together into larger panels.[8]: 55 [6]: 33 [3]: 166 [31]: 287–288 In Nasrid tilework the plaster was mixed with threads of esparto grass and cane to provide them with more tensile strength.[3]: 166 The panels were then affixed to the walls with a mortar or grout.[14]: 563 [6]: 33 In the case of the Almohad tilework on the minarets of the Kutubiyya and Kasbah Mosque in Marrakesh, the tiles were nailed to a wooden framework set into the surface of the wall behind them.[14]: 330

|

See also: Islamic geometric patterns |

In traditional zellij decoration, geometric patterns of varying complexity were the most prominent and widespread motif. Vegetal arabesque motifs were also used, though less frequently.[5] Geometric patterns were created on the basis of tessellation: the method of covering a surface with the use of forms that can be repeated and fitted together without overlapping or leaving empty spaces between them. These patterns can be extended infinitely.[32][6]: 21 In Islamic art, the most important types of tessellation in geometric motifs are based on regular polygons.[32] This form of expression within the conceptual framework of Islamic art valued the creation of spatial decorations that avoided depictions of living things, consistent with taboos of aniconism in Islam on such depictions.[4] Traditions of mosaic tilework were also prevalent across various periods in other parts of the Islamic world, including Iran, Anatolia, and the Indian subcontinent.[33] Whereas in the eastern Islamic world blues and turquoises were the dominant colours, in western zellij yellows, greens, black, and light brown were very common, with blues and turquoise also appearing in the mix, and they were typically set against a white ground.[5][33][34]

In western Islamic art, under the Nasrid and Marinid dynasties, a great variety of geometric patterns were created for architectural decoration. Among the most common was a pattern employing six-pointed and twelve-pointed star compositions, with eight-pointed stars inserted between them.[32]: 107 A popular trend was the use of patterns based on systems of fourfold symmetry. This family of patterns was widely used in other Muslim cultures further east, but in the Maghreb and al-Andalus artists excelled at their use and introduced several innovations. One innovation was to make the repeating unit of the patterns larger, with broader compositions involving many different polygonal forms. Other innovations were the incorporation of more complex sixteen-pointed stars into some of these patterns and the insertion of further "arbitrary" design elements within the wider patterns. These innovations not only increased the complexity of the motifs but also increased their visual diversity.[32]: 107–109 The family of patterns involving fivefold symmetry, which was widely used and developed throughout the rest of the Islamic world, was less common in the Maghreb and al-Andalus.[32]: 110 Some exceptional examples of this pattern from the Marinid period are found in the zellij tilework of the al-Attarine and Bou Inania madrasas in Fez, where greater visual diversity was once again achieved by using large repeating units.[32]: 111 In these examples and in others, additional visual diversity was also achieved through the use of colour. By varying the colours of the pieces, different patterns could be highlighted within the same geometric motif.[6]: 85 [32]: 111

Other types of compositions were also employed, many of them much simpler. Some mosaics were simply composed of coloured squares.[6][4] One variation of this is a "checkerboard"-like pattern made up of repeating squares/lozenges separated by white strips with eight-pointed stars at their intersections.[16]: 60–72 In the Alhambra of the Nasrids, some zellij motifs were composed of interlacing ribbons or tracery, sometimes as part of a narrow frieze wrapping around doorways or running above larger zellij dadoes.[6] Another motif distinctive to the Alhambra is the so-called "Nasrid bird" (Spanish: pajarita nazarí), which is composed of a three-pointed star with curved arms that is repeated in a wheel-like motif.[6] Yet another motif consists of one repeating curvilinear form resembling a double-headed axe, which is found in the Alhambra and is also common in the zellij of Tétouan in Morocco, where it is known in Arabic as the "four hammers" (arba'a matariq). A straight-lined version of this motif, similar to the 12th-century zellij on the minaret of the Kutubiyya Mosque, is also found in the Alhambra, where it is referred to in Spanish as the "bone" (hueso) motif.[6]: 22–23 [2]: 32–36 A darj-wa-ktaf (or sebka) motif is also employed in some Marinid tilework, including examples at the al-Attarine and Bou Inania madrasas.[22]: 138–153 [16]: 70–71 Numerous other tessellated motifs are attested.

An Aramco World article about zellij states:

An encyclopedia could not contain the full array of complex, often individually varied patterns and the individually shaped, hand-cut tesserae, or furmah, found in zillij work. Star-based patterns are identified by their number of points—'itnashari for 12, 'ishrini for 20, arba' wa 'ishrini for 24 and so on, but they are not necessarily named with exactitude. The so-called khamsini, for 50 points, and mi'ini, for 100, actually consist of 48 and 96 points respectively, because geometry requires that the number of points of any star in this sequence be divisible by six. (There are also sequences based on five and on eight.) Within a single star pattern, variations abound—by the mix of colors, the size of the furmah, and the complexity and size of interspacing elements such as strapping, braids, or "lanterns." And then there are all the non-star patterns— honeycombs, webs, steps and shoulders, and checkerboards.[35]

Islamic decoration and craftsmanship had a significant influence on Western art when Venetian merchants brought goods of many types back to Italy from the 14th century onwards.[36] The tessellations of zellij tilework in the Alhambra of Granada were also an important source of inspiration for the work of 20th-century Dutch artist M. C. Escher.[37][38][39] The tessellations in the mosaics are currently of interest in academic research in the mathematics of art. These studies require expertise not only in the fields of mathematics, art and art history, but also of computer science, computer modelling and software engineering.[40][additional citation(s) needed]

In Morocco, Fez is still a production center for zellīj tiles due in part to the Miocene grey clay found in the area. The clay from this region is primarily composed of kaolinite. In Fez and in other sites including Meknes, Safi, and Salé, the composition of clay used for ceramics is 27–56% clay minerals, of which 3–29% is calcite (around 16% for Fez).[41] Quartz and muscovite are also present, at around 15–29% and 5–18%, respectively.[41] A study by Meriam El Ouahabi, L. Daoudi, and Nathalie Fagel states that:

From the other sites (Meknes, Fes, Salé and Safi), the clay mineral composition shows besides kaolinite the presence of illite, chlorite, smectite and traces of mixed layer illite/chlorite. Meknes clays belong to illitic clays, characterized by illite (54 – 61%), kaolinite (11 – 43%), smectite (8 – 12%) and chlorite (6 – 19%). Fes clays have a homogeneous composition with illite (40 – 48%). and kaolinite (18 – 28%) as the most abundant clay minerals. Chlorite (12 – 15%) and smectite (9 – 12%) are generally present as small quantities. Mixed layer illite/chlorite is present in trace amounts in all the examined Fes clay materials.[41][failed verification]

Zellīj making is considered an art in itself. The art is transmitted from generation to generation by ma'alems (master craftsmen). A long training is required to implant the required skills and training usually starts at childhood. In Fez, craftsmen begin training between the ages of 6 and 14 and the average apprenticeship lasts approximately ten years, with many more years required to achieve the status of ma'alem.[29] In 1993, the Moroccan government ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), abolishing the practice of employing children under 15 in work that is hazardous or impedes their education,[42] but a 2019 study reports that the practice of training children has continued.[29] Now young people learn zellīj making at one of the 58 artisan schools in Morocco. However, the interest in learning the craft is dropping. As of 2018, at an artisan school in Fez with 400 enrolled students only 7 students learn how to make zellīj.[43]