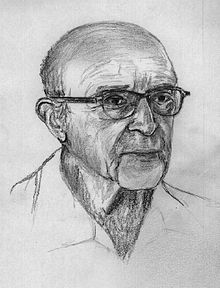

Carl Rogers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 8, 1902 Oak Park, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | February 4, 1987 (aged 85) San Diego, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Wisconsin–Madison (BA) Union Theological Seminary Columbia University (MA, PhD) |

| Known for | The person-centered approach (e.g., Client-centered therapy, Student-centered learning, Rogerian argument) |

| Children | Natalie Rogers David Elliot Rogers |

| Awards | Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions to Psychology (1956, APA); Award for Distinguished Contributions to Applied Psychology as a Professional Practice (1972, APA); 1964 Humanist of the Year (American Humanist Association) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychology |

| Institutions | Ohio State University University of Chicago University of Wisconsin–Madison Western Behavioral Sciences Institute Center for Studies of the Person |

Carl Ransom Rogers (January 8, 1902 – February 4, 1987) was an American psychologist who was one of the founders of humanistic psychology and was known especially for his person-centered psychotherapy. Rogers is widely considered one of the founding fathers of psychotherapy research and was honored for his pioneering research with the Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions by the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1956.

The person-centered approach, Rogers's approach to understanding personality and human relationships, found wide application in various domains, such as psychotherapy and counseling (client-centered therapy), education (student-centered learning), organizations, and other group settings.[1] For his professional work he received the Award for Distinguished Professional Contributions to Psychology from the APA in 1972. In a study by Steven J. Haggbloom and colleagues using six criteria such as citations and recognition, Rogers was found to be the sixth most eminent psychologist of the 20th century and second, among clinicians,[2] only to Sigmund Freud.[3] Based on a 1982 survey of 422 respondents of U.S. and Canadian psychologists, he was considered the most influential psychotherapist in history (Freud ranked third).[4]

Rogers was born on January 8, 1902, in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. His father, Walter A. Rogers, was a civil engineer, a Congregationalist by denomination. His mother, Julia M. Cushing,[5][6] was a homemaker and devout Baptist. Carl was the fourth of their six children.[7]

Rogers was intelligent and could read well before kindergarten. Following an education in a strict religious and ethical environment as an altar boy at the vicarage of Jimpley, he became rather isolated, independent and disciplined, and acquired knowledge and an appreciation for the scientific method in a practical world. At the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he was a member of the fraternity Alpha Kappa Lambda, his first career choice was agriculture, followed by history and then religion.

At age 20, following his 1922 trip to Beijing, China, for an international Christian conference, Rogers started to doubt his religious convictions. To help him clarify his career choice, he attended a seminar titled "Why Am I Entering the Ministry?" after which he decided to change careers. In 1924, he graduated from the University of Wisconsin, married Helen Elliott (a fellow Wisconsin student whom he had known from Oak Park), and enrolled at Union Theological Seminary in New York. Some time later he reportedly became an atheist.[8] Although referred to as an atheist early in his career, Rogers eventually came to be described as agnostic. However, in his later years it is reported he spoke about spirituality. Thorne, who knew Rogers and worked with him on a number of occasions during his final ten years, writes that "in his later years his openness to experience compelled him to acknowledge the existence of a dimension to which he attached such adjectives as mystical, spiritual, and transcendental".[9] Rogers concluded that there is a realm "beyond" scientific psychology, a realm he came to prize as "the indescribable, the spiritual."[10]

After two years, Rogers left the seminary to attend Teachers College, Columbia University, obtaining an M.A. in 1927 and a Ph.D. in 1931.[11] While completing his doctoral work, he engaged in child study. He studied with Alfred Adler in 1927 to 1928 when Rogers was an intern at the now defunct Institute for Child Guidance in New York City.[12] Later in life, Rogers recalled:

Accustomed as I was to the rather rigid Freudian approach of the Institute—seventy-five-page case histories, and exhaustive batteries of tests before even thinking of "treating" a child—I was shocked by Dr. Adler's very direct and deceptively simple manner of immediately relating to the child and the parent. It took me some time to realize how much I had learned from him.[12]

In 1930, Rogers served as director of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children in Rochester, New York. From 1935 to 1940 he lectured at the University of Rochester and wrote The Clinical Treatment of the Problem Child (1939), based on his experience in working with troubled children. He was strongly influenced in constructing his client-centered approach by the post-Freudian psychotherapeutic practice of Otto Rank,[10] especially as embodied in the work of Rank's disciple, noted clinician and social work educator Jessie Taft.[13][14] In 1940 Rogers became professor of clinical psychology at the Ohio State University, where he wrote his second book, Counseling and Psychotherapy (1942). In it, Rogers suggests that by establishing a relationship with an understanding, accepting therapist, a client can resolve difficulties and gain the insight necessary to restructure their life.

In 1945, Rogers was invited to set up a counseling center at the University of Chicago. In 1947, he was elected president of the American Psychological Association.[15] While a professor of psychology at the University of Chicago (1945–57), Rogers helped establish a counseling center connected with the university and there conducted studies to determine his methods' effectiveness. His findings and theories appeared in Client-Centered Therapy (1951) and Psychotherapy and Personality Change (1954). One of his graduate students at the University of Chicago, Thomas Gordon, established the Parent Effectiveness Training (P.E.T.) movement. Another student, Eugene T. Gendlin, who was getting his Ph.D. in philosophy, developed the practice of Focusing based on Rogerian listening. In 1956, Rogers became the first president of the American Academy of Psychotherapists.[16] He taught psychology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison (1957–63), during which time he wrote one of his best-known books, On Becoming a Person (1961). A student of his there, Marshall Rosenberg, went on to develop Nonviolent Communication.[17] Rogers and Abraham Maslow (1908–70) pioneered a movement called humanistic psychology, which reached its peak in the 1960s. In 1961, he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[18] Rogers was also one of the people who questioned the rise of McCarthyism in the 1950s. In articles, he criticized society for its backward-looking affinities.[19]

Rogers continued teaching at the University of Wisconsin until 1963, when he became a resident at the new Western Behavioral Sciences Institute (WBSI) in La Jolla, California. Rogers left the WBSI to help found the Center for Studies of the Person in 1968. His later books include Carl Rogers on Personal Power (1977) and Freedom to Learn for the '80s (1983). He remained a La Jolla resident for the rest of his life, doing therapy, giving speeches and writing.

Rogers's last years were devoted to applying his theories in situations of political oppression and national social conflict, traveling worldwide to do so. In Belfast, Northern Ireland, he brought together influential Protestants and Catholics; in South Africa, blacks and whites; in Brazil, people emerging from dictatorship to democracy; in the United States, consumers and providers in the health field. His last trip, at age 85, was to the Soviet Union, where he lectured and facilitated intensive experiential workshops fostering communication and creativity. He was astonished at how many Russians knew of his work.

Between 1974 and 1984, Rogers, his daughter Natalie Rogers, and psychologists Maria Bowen, Maureen O'Hara, and John K. Wood convened a series of residential programs in the U.S., Europe, Brazil and Japan, the Person-Centered Approach Workshops, which focused on cross-cultural communications, personal growth, self-empowerment, and learning for social change.

In 1987, Rogers suffered a fall that resulted in a fractured pelvis: he had life alert and was able to contact paramedics. He had a successful operation, but his pancreas failed the next night and he died a few days later after a heart attack.[20]

One of Rogers's most famous lines is: "Death is final, and accepting that is the most difficult thing to undertake. That loved one is not coming back and nothing can change that. Nothing compares to them. Life is precious and vulnerable, so be wise with how you choose to spend it, because once death arrives there is no turning back."

Rogers's theory of the self is considered humanistic, existential, and phenomenological.[21] It is based directly on the "phenomenal field" personality theory of Combs and Snygg (1949).[22] Rogers's elaboration of his theory is extensive. He wrote 16 books and many more journal articles about it. Prochaska and Norcross (2003) states Rogers "consistently stood for an empirical evaluation of psychotherapy. He and his followers have demonstrated a humanistic approach to conducting therapy and a scientific approach to evaluating therapy need not be incompatible."

Rogers's theory (as of 1951) was based on 19 propositions:[23]

In relation to No. 17, Rogers is known for practicing "unconditional positive regard", which is defined as accepting a person "without negative judgment of .... [a person's] basic worth".[24]

With regard to development, Rogers described principles rather than stages. The main issue is the development of a self-concept and the progress from an undifferentiated self to being fully differentiated.

Self Concept ... the organized consistent conceptual gestalt composed of perceptions of the characteristics of 'I' or 'me' and the perceptions of the relationships of the 'I' or 'me' to others and to various aspects of life, together with the values attached to these perceptions. It is a gestalt which is available to awareness though not necessarily in awareness. It is a fluid and changing gestalt, a process, but at any given moment it is a specific entity. (Rogers, 1959)[25]

In the development of the self-concept, he saw conditional and unconditional positive regard as key. Those raised in an environment of unconditional positive regard have the opportunity to fully actualize themselves. Those raised in an environment of conditional positive regard feel worthy only if they match conditions (what Rogers describes as conditions of worth) that others have laid down for them.

Optimal development, as referred to in proposition 14, results in a certain process rather than static state. Rogers calls this the good life, where the organism continually aims to fulfill its potential. He listed the characteristics of a fully functioning person (Rogers 1961):[26]

This process of the good life is not, I am convinced, a life for the faint-hearted. It involves the stretching and growing of becoming more and more of one's potentialities. It involves the courage to be. It means launching oneself fully into the stream of life. (Rogers 1961)[26]

Rogers identified the "real self" as the aspect of a person that is founded in the actualizing tendency, follows organismic values and needs, and receives positive regard from others and self. On the other hand, to the extent that society is out of sync with the actualizing tendency and people are forced to live with conditions of worth that are out of step with organismic valuing, receiving only conditional positive regard and self-regard, Rogers said that people develop instead an "ideal self". By ideal, he was suggesting something not real, something always out of reach, a standard people cannot meet. This gap between the real self and the ideal self, the "I am" and the "I should", Rogers called incongruity.

Rogers described the concepts of congruence and incongruence as important in his theory. In proposition #6, he refers to the actualizing tendency. At the same time, he recognized the need for positive regard. In a fully congruent person, realizing their potential is not at the expense of experiencing positive regard. They are able to lead authentic and genuine lives. Incongruent individuals, in their pursuit of positive regard, lead lives that include falsity and do not realize their potential. Conditions put on them by those around them make it necessary for them to forgo their genuine, authentic lives to meet with others' approval. They live lives that are not true to themselves.

Rogers suggested that the incongruent individual, who is always on the defensive and cannot be open to all experiences, is not functioning ideally and may even be malfunctioning. They work hard at maintaining and protecting their self-concept[citation needed]. Because their lives are not authentic, this is difficult, and they are under constant threat. They deploy defense mechanisms to achieve this. He describes two mechanisms: distortion and denial. Distortion occurs when the individual perceives a threat to their self-concept. They distort the perception until it fits their self-concept. This defensive behavior reduces the consciousness of the threat but not the threat itself. And so, as the threats mount, the work of protecting the self-concept becomes more difficult and the individual becomes more defensive and rigid in their self-structure. If the incongruity is immoderate this process may lead the individual to a state that would typically be described as neurotic. Their functioning becomes precarious and psychologically vulnerable. If the situation worsens it is possible that the defenses cease to function altogether and the individual becomes aware of the incongruity of their situation. Their personality becomes disorganised and bizarre; irrational behavior, associated with earlier denied aspects of self, may erupt uncontrollably.

|

Main articles: Person-centered therapy and Student-centered learning |

|

Main article: Person-centered therapy |

Rogers originally developed his theory as the foundation for a system of therapy. He initially called it "non-directive therapy" but later replaced the term "non-directive" with "client-centered", and still later "person-centered". Even before the publication of Client-Centered Therapy in 1951, Rogers believed the principles he was describing could be applied in a variety of contexts, not just in therapy. As a result, he started to use the term person-centered approach to describe his overall theory. Person-centered therapy is the application of the person-centered approach to therapy. Other applications include a theory of personality, interpersonal relations, education, nursing, cross-cultural relations and other "helping" professions and situations. In 1946 Rogers co-authored "Counseling with Returned Servicemen" with John L. Wallen (the creator of the behavioral model known as The Interpersonal Gap),[27] documenting the application of person-centered approach to counseling military personnel returning from World War II.

The first empirical evidence of the client-centered approach's effectiveness was published in 1941 at the Ohio State University by Elias Porter, using the recordings of therapeutic sessions between Rogers and his clients.[28] Porter used Rogers's transcripts to devise a system to measure the degree of directiveness or non-directiveness a counselor employed.[29] The counselor's attitude and orientation were shown to be instrumental in the decisions the client made.[30][31]

The application to education has a large robust research tradition similar to that of therapy, with studies having begun in the late 1930s and continuing today (Cornelius-White, 2007). Rogers described the approach to education in Client-Centered Therapy and wrote Freedom to Learn devoted exclusively to the subject in 1969. Freedom to Learn was revised twice. The new Learner-Centered Model is similar in many regards to this classical person-centered approach to education. Before Rogers's death, he and Harold Lyon began a book, On Becoming an Effective Teacher—Person-centered Teaching, Psychology, Philosophy, and Dialogues with Carl R. Rogers and Harold Lyon, that Lyon and Reinhard Tausch completed and published in 2013. It contains Rogers's last unpublished writings on person-centered teaching.[32] Rogers had the following five hypotheses regarding learner-centered education:

|

Main article: Rogerian rhetoric |

In 1970, Richard Young, Alton L. Becker, and Kenneth Pike published Rhetoric: Discovery and Change, a widely influential college writing textbook that used a Rogerian approach to communication to revise the traditional Aristotelian framework for rhetoric.[33] The Rogerian method of argument involves each side restating the other's position to the satisfaction of the other, among other principles.[33] In a paper, it can be expressed by carefully acknowledging and understanding the opposition, rather than dismissing them.[33][34]

The application to cross-cultural relations has involved workshops in highly stressful situations and global locations, including conflicts and challenges in South Africa, Central America, and Ireland.[35] Rogers, Alberto Zucconi, and Charles Devonshire co-founded the Istituto dell'Approccio Centrato sulla Persona (Person-Centered Approach Institute) in Rome, Italy.

Rogers's international work for peace culminated in the Rust Peace Workshop, which took place in November 1985 in Rust, Austria. Leaders from 17 nations convened to discuss the topic "The Central America Challenge". The meeting was notable for several reasons: it brought national figures together as people (not as their positions), it was a private event, and was an overwhelming positive experience where members heard one another and established real personal ties, as opposed to stiffly formal and regulated diplomatic meetings.[36]

Some scholars believe there is a politics implicit in Rogers's approach to psychotherapy.[37][38] Toward the end of his life, Rogers came to that view himself.[39] The central tenet of Rogerian, person-centered politics is that public life need not consist of an endless series of winner-take-all battles among sworn opponents; rather, it can and should consist of an ongoing dialogue among all parties. Such dialogue is characterized by respect among the parties, authentic speaking by each, and—ultimately—empathic understanding among all parties. Out of such understanding, mutually acceptable solutions will (or at least can) flow.[37][40]

During his last decade, Rogers facilitated or participated in a wide variety of dialogic activities among politicians, activists, and other social leaders, often outside the U.S.[40] He also lent his support to several non-traditional U.S. political initiatives, including the "12-Hour Political Party" of the Association for Humanistic Psychology[41] and the founding of a "transformational" political organization, the New World Alliance.[42] By the 21st century, interest in dialogic approaches to political engagement and change had become widespread, especially among academics and activists.[43] Theorists of a specifically Rogerian, person-centered approach to politics as dialogue have made substantial contributions to that project.[38][44]

From the late 1950s into the '60s, Rogers served on the board of the Human Ecology Fund, a CIA-funded organization that provided grants to researchers looking into personality. In addition, he and other people in the field of personality and psychotherapy were given a lot of information about Khrushchev. "We were asked to figure out what we thought of him and what would be the best way of dealing with him. And that seemed to be an entirely principled and legitimate aspect. I don't think we contributed very much, but, anyway, we tried."[45]

Howard Kirschenbaum has conducted extensive research on the work of Carl Rogers and the person-centered/client centered approach. Kirschenbaum published the first thorough book in English on Rogers’ life and work, titled, On Becoming Carl Rogers in 1979, followed by the biography, The Life and Work of Carl Rogers in 2007.[46]