| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

|

The Epistle to Philemon[a] is one of the books of the Christian New Testament. It is a prison letter, authored by Paul the Apostle (the opening verse also mentions Timothy), to Philemon, a leader in the Colossian church. It deals with the themes of forgiveness and reconciliation. Paul does not identify himself as an apostle with authority, but as "a prisoner of Jesus Christ", calling Timothy "our brother", and addressing Philemon as "fellow labourer" and "brother" (Philemon 1:1; 1:7; 1:20). Onesimus, a slave that had departed from his master Philemon, was returning with this epistle wherein Paul asked Philemon to receive him as a "brother beloved" (Philemon 1:9–17).

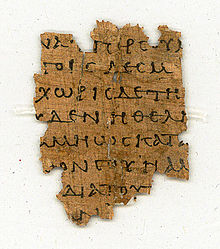

Philemon was a wealthy Christian, possibly a bishop[3] of the church that met in his home (Philemon 1:1–2) in Colossae. This letter is now generally regarded as one of the undisputed works of Paul. It is the shortest of Paul's extant letters, consisting of only 335 words in the Greek text.[4]

The Epistle to Philemon was composed around AD 57–62 by Paul while in prison at Caesarea Maritima (early date) or more likely from Rome (later date) in conjunction with the composition of Colossians.[5]

The Epistle to Philemon is attributed to the apostle Paul, and this attribution has rarely been questioned by scholars.[6] Along with six others, it is numbered among the "undisputed letters", which are widely considered to be authentically Pauline. The main challenge to the letter's authenticity came from a group of German scholars in the nineteenth century known as the Tübingen School.[7] Their leader, Ferdinand Christian Baur, only accepted four New Testament epistles as genuinely written by Paul: Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians and Galatians. Commenting on Philemon, Baur described the subject matter as "so very singular as to arouse our suspicions",[8] and concluded that it is perhaps a "Christian romance serving to convey a genuine Christian idea".[9] This view is now largely considered to be outdated and finds no support in modern scholarship.

The opening verse of the salutation also names Timothy alongside Paul. This, however, does not mean that Timothy was the epistle's co-author. Rather, Paul regularly mentions others in the address if they have a particular connection with the recipient. In this case, Timothy may have encountered Philemon while accompanying Paul in his work in Ephesus.[10]

According to the most common interpretation, Paul wrote this letter on behalf of Onesimus, a runaway slave who had wronged his owner Philemon.[clarification needed] The details of the offence are unstated, although it is often assumed that Onesimus had fled after stealing money, as Paul states in verse 18 that if Onesimus owes anything, Philemon should charge this to Paul's account.[11] Sometime after leaving, Onesimus came into contact with Paul, although again the details are unclear. He may have been arrested and imprisoned alongside Paul. Alternatively, he may have previously heard Paul's name (as his owner was a Christian) and so travelled to him for help.[11] After meeting Paul, Onesimus became a Christian believer. An affection grew between them, and Paul would have been glad to keep Onesimus with him. However, he considered it better to send him back to Philemon with an accompanying letter, which aimed to effect reconciliation between them as Christian brothers. The preservation of the letter suggests that Paul's request was granted.[12]

Onesimus' status as a runaway slave was challenged by Allen Dwight Callahan in an article published in the Harvard Theological Review and in a later commentary. Callahan argues that, beyond verse 16, "nothing in the text conclusively indicates that Onesimus was ever the chattel of the letter's chief addressee. Moreover, the expectations fostered by the traditional fugitive slave hypothesis go unrealized in the letter. Modern commentators, even those committed to the prevailing interpretation, have tacitly admitted as much."[13] Callahan argues that the earliest commentators on this work – the homily of Origen and the Anti-Marcion Preface – are silent about Onesimus' possible servile status, and traces the origins of this interpretation to John Chrysostom, who proposed it in his Homiliae in epistolam ad Philemonem, during his ministry in Antioch, circa 386–398.[14] In place of the traditional interpretation, Callahan suggests that Onesimus and Philemon are brothers both by blood and religion, but who have become estranged, and the intent of this letter was to reconcile the two men.[15] Ben Witherington III has challenged Callahan's interpretation as a misreading of Paul's rhetoric.[16] Further, Margaret M. Mitchell has demonstrated that a number of writers before Chrysostom either argue or assume that Onesimus was a runaway slave, including Athanasius, Basil of Caesarea and Ambrosiaster.[17]

The only extant information about Onesimus apart from this letter is found in Paul's epistle to the Colossians 4:7–9, where Onesimus is called "a faithful and beloved brother":

All my state shall Tychicus declare unto you, who is a beloved brother, and a faithful minister and fellow servant in the Lord: 8 Whom I have sent unto you for the same purpose, that he might know your estate, and comfort your hearts; 9 With Onesimus, a faithful and beloved brother, who is one of you. They shall make known unto you all things which are done here.

The letter is addressed to Philemon, Apphia and Archippus, and the church in Philemon's house. Philemon is described as a "fellow worker" of Paul. It is generally assumed that he lived in Colossae; in the letter to the Colossians, Onesimus (the slave who fled from Philemon) and Archippus (whom Paul greets in the letter to Philemon) are described as members of the church there.[18] Philemon may have converted to Christianity through Paul's ministry, possibly in Ephesus.[19] Apphia in the salutation is probably Philemon's wife.[11] Some have speculated that Archippus, described by Paul as a "fellow soldier", is the son of Philemon and Apphia.[11]

The Scottish Pastor John Knox proposed that Onesimus' owner was in fact Archippus, and the letter was addressed to him rather than Philemon. In this reconstruction, Philemon would receive the letter first and then encourage Archippus to release Onesimus so that he could work alongside Paul. This view, however, has not found widespread support.[11] In particular, Knox's view has been challenged on the basis of the opening verses. According to O'Brien, the fact that Philemon's name is mentioned first, together with the use of the phrase "in your house" in verse 2, makes it unlikely that Archippus was the primary addressee.[11] Knox further argued that the letter was intended to be read aloud in the Colossian church in order to put pressure on Archippus. A number of commentators, however, see this view as contradicting the tone of the letter.[20][12] J. B. Lightfoot, for example, wrote: "The tact and delicacy of the Apostle's pleading for Onesimus would be nullified at one stroke by the demand for publication."[21]

The opening salutation follows a typical pattern found in other Pauline letters. Paul first introduces himself, with a self-designation as a "prisoner of Jesus Christ," which in this case refers to a physical imprisonment. He also mentions his associate Timothy, as a valued colleague who was presumably known to the recipient. As well as addressing the letter to Philemon, Paul sends greetings to Apphia, Archippus and the church that meets in Philemon's house. Apphia is often presumed to be Philemon's wife and Archippus, a "fellow labourer", is sometimes suggested to be their son. Paul concludes his salutation with a prayerful wish for grace and peace.[22]

Before addressing the main topic of the letter, Paul continues with a paragraph of thanksgiving and intercession. This serves to prepare the ground for Paul's central request. He gives thanks to God for Philemon's love and faith and prays for his faith to be effective. He concludes this paragraph by describing the joy and comfort he has received from knowing how Philemon has shown love towards the Christians in Colossae.[23]

As a background to his specific plea for Onesimus, Paul clarifies his intentions and circumstances. Although he has the boldness to command Philemon to do what would be right in the circumstances, he prefers to base his appeal on his knowledge of Philemon's love and generosity. He also describes the affection he has for Onesimus and the transformation that has taken place with Onesimus's conversion to the Christian faith. Where Onesimus was "useless", now he is "useful" – a wordplay, as Onesimus means "useful". Paul indicates that he would have been glad to keep Onesimus with him, but recognised that it was right to send him back. Paul's specific request is for Philemon to welcome Onesimus as he would welcome Paul, namely as a Christian brother. He offers to pay for any debt created by Onesimus' departure and expresses his desire that Philemon might refresh his heart in Christ.[24]

In the final section of the letter, Paul describes his confidence that Philemon would do even more than he had requested, perhaps indicating his desire for Onesimus to return to work alongside him. He also mentions his wish to visit and asks Philemon to prepare a guest room. Paul sends greetings from five of his co-workers and concludes the letter with a benediction.[25]

Paul uses slavery vs. freedom language more often in his writings as a metaphor.[26]

This letter may have provided some comfort to some slaves of the time.[27]

Though its practice appears centrally, Paul does not share value judgements about the institution of slavery. Its influence could create pressures, as an “abolitionist would have been at the same time an insurrectionist, and the political effects of such a movement would have been unthinkable."[28] Paul saw human institutions like slavery among many that in his apocalyptic view would soon go.[28]

When it comes to Onesimus and his circumstance as a slave, Paul felt that Onesimus should return to Philemon but not as a slave; rather, under a bond of familial love. Paul also was not suggesting that Onesimus be punished, in spite of the fact that Roman law allowed the owner of a runaway slave nearly unlimited privileges of punishment, even execution.[29] This is a concern of Paul and a reason he is writing to Philemon, asking that Philemon accept Onesimus back in a bond of friendship, forgiveness, and reconciliation. Paul is undermining this example of a human institution which dehumanizes people.[29] Onesimus, like Philemon, belongs to Christ, and so "Christ, and not Philemon, has a claim on Onesimus' honor and obedience."[30]

Verses 13–14 suggest that Paul wants Philemon to send Onesimus back to Paul (possibly freeing him for the purpose). Marshall, Travis and Paul write, "Paul hoped that it might be possible for [Onesimus] to spend some time with him as a missionary colleague... If that is not a request for Onesimus to join Paul’s circle, I do not know what more would need to be said".[31]

In his A History of Christianity, Diarmaid MacCulloch described the epistle as "a Christian foundation document in the justification of slavery".[32]

In order to better appreciate the Book of Philemon, it is necessary to be aware of the situation of the early Christian community in the Roman Empire; and the economic system of Classical Antiquity based on slavery. According to the Epistle to Diognetus: For the Christians are distinguished from other men neither by country, nor language, nor the customs which they observe... They are in the flesh, but they do not live after the flesh. They pass their days on earth, but they are citizens of heaven. They obey the prescribed laws, and at the same time surpass the laws by their lives.[33]

Pope Benedict XVI refers to this letter in his encyclical letter, Spe salvi, highlighting the power of Christianity as power of the transformation of society:

Those who, as far as their civil status is concerned, stand in relation to one an other as masters and slaves, inasmuch as they are members of the one Church have become brothers and sisters—this is how Christians addressed one another... Even if external structures remained unaltered, this changed society from within. When the Letter to the Hebrews says that Christians here on earth do not have a permanent homeland, but seek one which lies in the future (cf. Heb 11:13–16; Phil 3:20), this does not mean for one moment that they live only for the future: present society is recognized by Christians as an exile; they belong to a new society which is the goal of their common pilgrimage and which is anticipated in the course of that pilgrimage.[34]

| Hebrew Bible / Old Testament (protocanon) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deuterocanon and apocrypha |

| ||||||||||||

| New Testament | |||||||||||||

| Subdivisions | |||||||||||||

| Development | |||||||||||||

| Manuscripts | |||||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||||

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |