| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

|

The First Epistle to the Corinthians[a] (Ancient Greek: Α΄ ᾽Επιστολὴ πρὸς Κορινθίους) is one of the Pauline epistles, part of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-author, Sosthenes, and is addressed to the Christian church in Corinth.[3] Despite the name, it is not believed to be the first such letter. Scholars believe that Sosthenes was the amanuensis who wrote down the text of the letter at Paul's direction.[4] It addresses various issues that had arisen in the Christian community at Corinth and is composed in a form of Koine Greek.[5]

There is a consensus among historians and theologians that Paul is the author of the First Epistle to the Corinthians (c. AD 53–54).[6] The letter is quoted or mentioned by the earliest of sources and is included in every ancient canon, including that of Marcion of Sinope.[7] Some scholars point to the epistle's potentially embarrassing references to the existence of sexual immorality in the church as strengthening the case for the authenticity of the letter.[8][9]

However, the epistle does contain a passage that is widely believed to have been interpolated into the text by a later scribe:[10]

As in all the churches of the saints, women should be silent in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak, but should be subordinate, as the law also says. If there is anything they desire to know, let them ask their husbands at home. For it is shameful for a woman to speak in church.

— 1 Corinthians 14:34–35, New Revised Standard Version[11]

Verses 34–35 are included in all extant manuscripts. Part of the reason for suspecting that this passage is an interpolation is that in several manuscripts in the Western tradition, it is placed at the end of chapter 14 instead of at its canonical location. This kind of variability is generally considered by textual critics to be a sign that a note, initially placed in the margins of the document, has been copied into the body of the text by a scribe.[12] As E. Earle Ellis and Daniel B. Wallace note, however, a marginal note may well have been written by Paul himself. The loss of marginal arrows or other directional devices could explain why the scribe of the Western Vorlage placed it at the end of the chapter. The absence of an asterisk or obelisk in the margin of any manuscript – a common way of indicating doubt of authenticity – they argue, a strong argument that Paul wrote the passage and intended it in its traditional place.[10] The passage has also been taken to contradict 11:5, where women are described as praying and prophesying in church.[12]

Furthermore, some scholars believe that the passage 1 Corinthians 10:1–22[13] constitutes a separate letter fragment or scribal interpolation because it equates the consumption of meat sacrificed to idols with idolatry, while Paul seems to be more lenient on this issue in 8:1–13[14] and 10:23–11:1.[15][16] Such views are rejected by other scholars who give arguments for the unity of 8:1–11:1.[17][18]

About the year AD 50, towards the end of his second missionary journey, Paul founded the church in Corinth before moving on to Ephesus, a city on the west coast of today's Turkey, about 290 kilometres (180 mi) by sea from Corinth. From there he traveled to Caesarea and Antioch. Paul returned to Ephesus on his third missionary journey and spent approximately three years there.[19] It was while staying in Ephesus that he received disconcerting news of the community in Corinth regarding jealousies, rivalry, and immoral behavior.[20] It also appears that, based on a letter the Corinthians sent Paul,[21] the congregation was requesting clarification on a number of matters, such as marriage and the consumption of meat previously offered to idols.

By comparing Acts of the Apostles 18:1–17[22] and mentions of Ephesus in the Corinthian correspondence, scholars suggest that the letter was written during Paul's stay in Ephesus, which is usually dated as being in the range of AD 53–57.[23][24]

Anthony C. Thiselton suggests that it is possible that 1 Corinthians was written during Paul's first (brief) stay in Ephesus, at the end of his second journey, usually dated to early AD 54.[25] However, it is more likely that it was written during his extended stay in Ephesus, where he refers to sending Timothy to them.[26][20]

Despite the attributed title "1 Corinthians", this letter was not the first written by Paul to the church in Corinth, only the first canonical letter. 1 Corinthians is the second known letter of four from Paul to the church in Corinth, as evidenced by Paul's mention of his previous letter in 1 Corinthians 5:9.[27] The other two being what is called the Second Epistle to the Corinthians and a "tearful, severe" letter mentioned in 2 Corinthians 2:3–4.[27] The book called the Third Epistle to the Corinthians is generally not believed by scholars to have been written by Paul, as the text claims.

The original manuscript of this book is lost, and the text of surviving manuscripts varies. The oldest manuscripts containing some or all of the text of this book include:

The epistle may be divided into seven parts:[31]

Now concerning the contribution for the saints: as I directed the churches of Galatia [...] Let all your things be done with charity. Greet one another with a holy kiss [...] I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand. If any man love not the Lord Jesus Christ, let him be Anathema Maranatha. The grace of the Lord Jesus be with you. My love be with you all in Christ Jesus. Amen.

— 1 Corinthians 16:1–24[33]

Some time before 2 Corinthians was written, Paul paid the church at Corinth a second visit[34] to check some rising disorder,[35] and wrote them a letter, now lost.[36] The church had also been visited by Apollos,[37] perhaps by Peter,[38] and by some Jewish Christians who brought with them letters of commendation from Jerusalem.[39]

Paul wrote 1 Corinthians letter to correct what he saw as erroneous views in the Corinthian church. Several sources informed Paul of conflicts within the church at Corinth: Apollos,[40] a letter from the Corinthians, "those of Chloe", and finally Stephanas and his two friends who had visited Paul.[41] Paul then wrote this letter to the Corinthians, urging uniformity of belief ("that ye all speak the same thing and that there be no divisions among you", 1:10) and expounding Christian doctrine. Titus and a brother whose name is not given were probably the bearers of the letter to the church at Corinth.[42]

In general, divisions within the church at Corinth seem to be a problem, and Paul makes it a point to mention these conflicts in the beginning. Specifically, pagan roots still hold sway within their community. Paul wants to bring them back to what he sees as correct doctrine, stating that God has given him the opportunity to be a "skilled master builder" to lay the foundation and let others build upon it.[43]

1 Corinthians 6:9-10 contains a notable condemnation of homosexuality, idolatry, thievery, drunkenness, slandering, swindling, adultery, and other acts the authors consider sexually immoral.

The majority of early manuscripts end chapter 6 with the words δοξάσατε δὴ τὸν Θεὸν ἐν τῷ σώματι ὑμῶν, doxasate de ton theon en tō sōmati humōn, 'therefore glorify God in your body'. The Textus Receptus adds καὶ ἐν τῷ πνεύματι ὑμῶν, ἅτινά ἐστι τοῦ Θεοῦ, kai en to pneumati humōn, hatina esti tou theou, which the New King James Version translates as "and in your spirit, which are (i.e. body and spirit) God's".[44] The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges notes that "these words are not found in many of the best MSS. and versions, and they somewhat weaken the force of the argument, which is intended to assert the dignity of the body. They were perhaps inserted by some who, missing the point of the Apostle's argument, thought that the worship of the spirit was unduly passed over."[45]

Later, Paul wrote about immorality in Corinth by discussing an immoral brother, how to resolve personal disputes, and sexual purity. Regarding marriage, Paul states that it is better for Christians to remain unmarried, but that if they lacked self-control, it is better to marry than "burn" (πυροῦσθαι). The epistle may include marriage as an apostolic practice in 1 Corinthians 9:5, "Do we not have the right to be accompanied by a believing wife, as do the other apostles and the brothers of the Lord and Cephas (Peter)?" (In the last case, the letter concurs with Matthew 8:14, which mentions Peter having a mother-in-law and thus, by inference, a wife.) However, the Greek word for 'wife' is the same word for 'woman'. The Early Church Fathers, including Tertullian, Jerome, and Augustine state the Greek word is ambiguous and the women in 1 Corinthians 9:5 were women ministering to the Apostles as women ministered to Christ,[46] and were not wives,[47] and assert they left their "offices of marriage" to follow Christ.[48] Paul also argues that married people must please their spouses, just as every Christian must please God.

Throughout the letter, Paul presents issues that are troubling the community in Corinth and offers ways to fix them. Paul states that this letter is to "admonish" them as beloved children. They are expected to become imitators of Jesus and follow the ways in Christ as he, Paul, teaches in all his churches.[49]

This epistle contains some well-known phrases, including: "all things to all men",[50]"through a glass, darkly",[51] and:

When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

— 1 Corinthians 13:11, King James Version.[52]

1 Corinthians 13:12 contains the phrase βλέπομεν γὰρ ἄρτι δι' ἐσόπτρου ἐν αἰνίγματι, blepomen gar arti di esoptrou en ainigmati, which was translated in the 1560 Geneva Bible as "For now we see through a glass darkly" (without a comma). This wording was used in the 1611 KJV, which added a comma before "darkly".[53] This passage has inspired the titles of many works, with and without the comma.

The Greek word ἐσόπτρου, esoptrou (genitive; nominative: ἔσοπτρον, esoptron), here translated "glass", is ambiguous, possibly referring to a mirror or a lens. Influenced by Strong's Concordance, many modern translations conclude that this word refers specifically to a mirror.[54] Example English language translations include:

Paul's usage is in keeping with rabbinic use of the term אספקלריה, aspaklaria, a borrowing from the Latin specularia. This has the same ambiguous meaning, although Adam Clarke concluded that it was a reference to specularibus lapidibus, clear polished stones used as lenses or windows.[55] One way to preserve this ambiguity is to use the English cognate, speculum.[56] Rabbi Judah ben Ilai (2nd century) was quoted as saying "All the prophets had a vision of God as He appeared through nine specula" while "Moses saw God through one speculum."[57] The Babylonian Talmud states similarly "All the prophets gazed through a speculum that does not shine, while Moses our teacher gazed through a speculum that shines."[58]

The letter is also notable for mentioning the role of women in churches, that for instance they must remain silent,[59] and yet they have a role of prophecy and apparently speaking tongues in churches.[60] If verse 14:34–35 is not an interpolation, certain scholars resolve the tension between these texts by positing that wives were either contesting their husband's inspired speeches at church, or the wives/women were chatting and asking questions in a disorderly manner when others were giving inspired utterances. Their silence was unique to the particular situation in the Corinthian gatherings at that time, and on this reading, Paul did not intend his words to be universalized for all women of all churches of all eras.[61]

1 Corinthians 11:2–16 contains an admonishment that Christian women cover their hair while praying and that Christian men leave their heads uncovered while praying. These practices were countercultural; the surrounding pagan Greek women prayed unveiled and Jewish men prayed with their heads covered.[62][63]

The King James Version of 1 Corinthians 11:10 reads "For this cause ought the woman to have power on her head because of the angels." Other versions translate "power" as "authority". In many early biblical manuscripts (such as certain Vulgate, Coptic, and Armenian manuscripts), is rendered with the word "veil" (κάλυμμα, kalumma) rather than the word "authority" (ἐξουσία, exousia); the Revised Standard Version reflects this, displaying 1 Corinthians 11:10[64] as follows: "That is why a woman ought to have a veil on her head, because of the angels."[65] Similarly, a scholarly footnote in the New American Bible notes that presence of the word "authority (exousia) may possibly be due to mistranslation of an Aramaic word for veil".[66] This mistranslation may be due to "the fact that in Aramaic the roots of the word power and veil are spelled the same."[67] The last-known living connection to the apostles, Irenaeus, penned verse 10 using the word "veil" (κάλυμμα, kalumma) instead of "authority" (ἐξουσία, exousia) in Against Heresies, as did other Church Fathers in their writings, including Hippolytus, Origen, Chrysostom, Jerome, Epiphanius, Augustine, and Bede.[65][68]

This ordinance continued to be handed down after the apostolic era to the next generations of Christians; writing 150 years after Paul, the early Christian apologist Tertullian stated that the women of the church in Corinth—both virgins and married—practiced veiling, given that Paul the Apostle delivered the teaching to them: "the Corinthians themselves understood him in this manner. In fact, at this very day, the Corinthians do veil their virgins. What the apostles taught, their disciples approve."[69] From the period of the early Church to the late modern period, 1 Corinthians 11 was universally understood to enjoin the wearing of the headcovering throughout the day—a practice that has since waned in Western Europe but has continued in certain parts of the world, such as in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Northern Africa and the Indian subcontinent,[70][71][72][73][74][75] as well as everywhere by Conservative Anabaptists (such as the Conservative Mennonite Churches and the Dunkard Brethren Church), who count veiling as being one of the ordinances of the Church.[76][77] The early Church Father John Chrysostom explicates that 1 Corinthians 11 enjoins the continual wearing the headcovering by referencing Paul the Apostle's view that being shaven is always dishonourable and his pointing to the angels:[78]

Chapter 13 of 1 Corinthians is one of many definitional sources for the original Greek word ἀγάπη, agape.[79] In the original Greek, the word ἀγάπη, agape is used throughout chapter 13. This is translated into English as "charity" in the King James version; but the word "love" is preferred by most other translations, both earlier and more recent.[80]

1 Corinthians 11:17-34 contains a condemnation of what the authors consider inappropriate behavior at Corinthian gatherings that appeared to be agape feasts.

After discussing his views on worshipping idols, Paul ends the letter with his views on resurrection and the Resurrection of Jesus. Key verses are often cited as a concise summary of core Christian doctrine or kerygma, and are used in the construction of various Christian creeds:

3 For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures 4 and that he was buried and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures 5 and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. 6 Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have died. 7 Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles.

— 1 Corinthians 15:3–7, New Revised Standard Version[81]

Belief in the death, burial, resurrection, and reappearance to Peter and the Twelve in verses 3–5, are assumed to be an early pre-Pauline kerygma or creedal statement.[b] Biblical scholars note the antiquity of the creed,[c] possibly transmitted from the Jerusalem apostolic community.[d][e] though the core formula may have originated in Damascus,[86] with the specific appearances reflecting the Jerusalem community.[f] It may be one of the earliest kerygmas about Jesus' death and resurrection, though it is also possible that Paul himself joined together the various statements, as proposed by Urich Wilckens.[88] It is also possible that "he appeared" was not specified in the core formula, and that the specific appearances are additions.[89] According to Hannack, line 3b-4 form the original core, while line 5 and line 7 contain competing statements from two different factions.[90] Prive also argues that line 5 and line 7 reflect the tensions between Petrus and James.[91]

The kerygma has often been dated to no more than five years after Jesus' death by Biblical scholars.[d] Bart Ehrman dissents, saying that "Among scholars I personally know, except for evangelicals, I don't now[sic] anyone who thinks this at all."[92][g] Gerd Lüdemann however, maintains that "the elements in the tradition are to be dated to the first two years after the crucifixion of Jesus [...] not later than three years".[93]

For orthodox Christians, the resurrection, believed by them to be a physical resurrection, is the central event of the Christian faith. While the authenticity of line 6a and 7 is disputed, MacGregor argues that linguistic analysis suggests that the version received by Paul seems to have included verses 3b–6a and 7.[94] According to Gary R. Habermas, in "Corinthians 15:3–8, Paul records an ancient oral tradition(s) that summarizes the content of the Christian gospel."[95] N.T Wright describes it as "the very early tradition that was common to all Christians."[96]

In dissent from the majority view, Robert M. Price,[97] Hermann Detering,[98] John V. M. Sturdy,[99] and David Oliver Smith[100] have each argued that 1 Corinthians 15:3–7 is a later interpolation. According to Price, the text is not an early Christian creed written within five years of Jesus' death, nor did Paul write these verses. In his assessment, this was an Interpolation possibly dating to the beginning of the 2nd century. Price states that "The pair of words in verse 3a, "received / delivered" (paralambanein / paradidonai) is, as has often been pointed out, technical language for the handing on of rabbinical tradition", so it would contradict Paul's account of his conversion given in Galatians 1:13–24, which explicitly says that Paul had been taught the gospel of Christ by Jesus himself, not by any other man.[91][h]

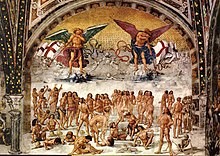

Paul then asks: "Now if Christ is preached as raised from the dead, how can some of you say that there is no resurrection of the dead?"[102] Chapter 15 closes with an account of the nature of the resurrection, claiming that in the Last Judgement the dead will be raised and both the living and the dead transformed into "spiritual bodies" (verse 44).[103]

1 Corinthians 15:27[104] refers to Psalm 8:6.[105] Ephesians 1:22 also refers to this verse of Psalm 8.[105]

1 Corinthians 15:33 contains the aphorism "evil company corrupts good habits", from classical Greek literature. According to the church historian Socrates of Constantinople[106] it is taken from a Greek tragedy of Euripides, but modern scholarship, following Jerome[107] attributes it to the comedy Thaĩs by Menander, or Menander quoting Euripides. Hans Conzelmann remarks that the quotation was widely known.[108] Whatever the proximate source, this quote does appear in one of the fragments of Euripides' works.[109]

1 Corinthians 15:29 argues it would be pointless to baptise the dead if people are not raised from the dead. This verse suggests that there existed a practice at Corinth whereby a living person would be baptized in the stead of some convert who had recently died.[110] Teignmouth Shore, writing in Ellicott's Commentary for Modern Readers, notes that among the "numerous and ingenious conjectures" about this passage, the only tenable interpretation is that there existed a practice of baptising a living person to substitute those who had died before that sacrament could have been administered in Corinth, as also existed among the Marcionites in the second century, or still earlier than that, among a sect called "the Corinthians".[111] The Jerusalem Bible states that "What this practice was is unknown. Paul does not say if he approved of it or not: he uses it merely for an ad hominem argument".[112]

The Latter Day Saint movement interprets this passage to support the practice of baptism for the dead. This principle of vicarious work for the dead is an important work of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the dispensation of the fulness of times. This interpretation is rejected by other denominations of Christianity.[113][114][115]

St. John Chrysostom, bishop of Constantinople and Doctor of the Catholic Church, wrote a commentary on 1 Corinthians, formed by 44 homilies.[116]

Furthermore, Greek women, including women in prayer, were usually depicted without a garment covering the head. It does not make sense that Paul would assert something was disgraceful that in their culture was not considered disgraceful. Concerning Greek customs A. Oepke observes: [...] It is quite wrong [to assert] that Greek women were under some kind of compulsion to wear a veil. [...] Passages to the contrary are so numerous and unequivocally that they cannot be offset. [...] Empresses and goddesses, even those who maintain their dignity, like Hera and Demeter, are portrayed without veils.

The [male] Jews of this era worshipped and prayed with a covering called a tallith on their heads.

...that the word translated in verses 5 and 13 as "uncovered" is akatakaluptos and means "unveiled" and the word translated in verse 6 as "covered" is katakalupto which means to "cover wholly, [or] veil". The word power in verse 10 may have also been mistranslated because the fact that in Aramaic the roots of the word power and veil are spelled the same.

Today many people associate rules about veiling and headscarves with the Muslim world, but in the eighteenth century they were common among Christians as well, in line with 1 Corinthians 11:4–13 which appears not only to prescribe headcoverings for any women who prays or goes to church, but explicitly to associate it with female subordination, which Islamic veiling traditions do not typically do. Many Christian women wore a head-covering all the time, and certainly when they went outside; those who did not would have been barred from church and likely harassed on the street. [...] Veils were, of course, required for Catholic nuns, and a veil that actually obscured the face was also a mark of elite status throughout most of Europe. Spanish noblewomen wore them well into the eighteenth century, and so did Venetian women, both elites and non-elites. Across Europe almost any woman who could afford them also wore them to travel.

Head covers are generally associated with Islam, but until recently Christian women in Mediterranean countries also covered their heads in public, and some still do, particularly in religious contexts such as attending mass.

Inside her house a Christian woman usually did not cover hear head and only wore a netsela (ነጠላ, a shawl made from white, usually homespun cotton and often with a colorful banner woven into its edges) when working in the sun or going out of her compound.

As a mark of respect, Indian women were expected to cover their heads. And over the years, most rural Hindu, Muslim and Christian women have done so with the Orhni, a thin shawl-like head covering.

Further north, in Vojvodina, some older Slovak women still regularly wear the headscarf, pleated skirt and embroidered apron that is their national dress. All across Serbia, as elsewhere in eastern Europe, many older women wear headscarves

There are Christian women in the Middle East who cover their hair and heads daily. Some wear burkas too.

| Persons | |

|---|---|

| Phrases | |

| Chapters | |

| Related | |

| Hebrew Bible / Old Testament (protocanon) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deuterocanon and apocrypha |

| ||||||||||||

| New Testament | |||||||||||||

| Subdivisions | |||||||||||||

| Development | |||||||||||||

| Manuscripts | |||||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||||

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |