The Viruses Portal

Welcome!

Viruses are small infectious agents that can replicate only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all forms of life, including animals, plants, fungi, bacteria and archaea. They are found in almost every ecosystem on Earth and are the most abundant type of biological entity, with millions of different types, although only about 6,000 viruses have been described in detail. Some viruses cause disease in humans, and others are responsible for economically important diseases of livestock and crops.

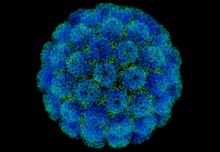

Virus particles (known as virions) consist of genetic material, which can be either DNA or RNA, wrapped in a protein coat called the capsid; some viruses also have an outer lipid envelope. The capsid can take simple helical or icosahedral forms, or more complex structures. The average virus is about 1/100 the size of the average bacterium, and most are too small to be seen directly with an optical microscope.

The origins of viruses are unclear: some may have evolved from plasmids, others from bacteria. Viruses are sometimes considered to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce and evolve through natural selection. However they lack key characteristics (such as cell structure) that are generally considered necessary to count as life. Because they possess some but not all such qualities, viruses have been described as "organisms at the edge of life".

Selected disease

Yellow fever is an acute haemorrhagic fever caused by the yellow fever virus, an RNA virus in the Flaviviridae family. It infects humans, other primates, and Aedes aegypti and other mosquito species, which act as the vector. After transmission by the bite of a female mosquito, the virus replicates in lymph nodes, infecting dendritic cells, and can then spread to liver hepatocytes. Symptoms generally last 3–4 days, and include fever, nausea and muscle pain. In around 15% of people, a toxic phase follows with recurring fever, liver damage and jaundice, sometimes accompanied by bleeding and kidney failure; death occurs in 20–50% of those who develop jaundice. Infection otherwise leads to lifelong immunity.

The first definitive outbreak of yellow fever was in Barbados in 1647, and major epidemics have occurred in the Americas and southern Europe since that date. Yellow fever is endemic in tropical and subtropical areas of South America and Africa; its incidence has been increasing since the 1980s. An estimated 200,000 cases and 30,000 deaths occur each year, with almost 90% of cases being in Africa. Antiviral therapy is not effective. A vaccine is available, and vaccination, mosquito control and bite prevention are the main preventive measures.

Selected image

The Varroa destructor mite can transmit viruses, including deformed wing virus, to its honey bee host. This might contribute to colony collapse disorder, in which worker bees abruptly disappear.

Credit: Eric Erbe & Christopher Pooley

In the news

26 February: In the ongoing pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), more than 110 million confirmed cases, including 2.5 million deaths, have been documented globally since the outbreak began in December 2019. WHO

18 February: Seven asymptomatic cases of avian influenza A subtype H5N8, the first documented H5N8 cases in humans, are reported in Astrakhan Oblast, Russia, after more than 100,0000 hens died on a poultry farm in December. WHO

14 February: Seven cases of Ebola virus disease are reported in Gouécké, south-east Guinea. WHO

7 February: A case of Ebola virus disease is detected in North Kivu Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. WHO

4 February: An outbreak of Rift Valley fever is ongoing in Kenya, with 32 human cases, including 11 deaths, since the outbreak started in November. WHO

21 November: The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gives emergency-use authorisation to casirivimab/imdevimab, a combination monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy for non-hospitalised people twelve years and over with mild-to-moderate COVID-19, after granting emergency-use authorisation to the single mAb bamlanivimab earlier in the month. FDA 1, 2

18 November: The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Équateur Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo, which started in June, has been declared over; a total of 130 cases were recorded, with 55 deaths. UN

Selected article

Vaccination or immunisation is the administration of immunogenic material (a vaccine) to stimulate an individual's immune system to develop adaptive immunity to a virus or other pathogen, and so develop protection against an infectious disease. The active agent of a vaccine may be intact but inactivated or weakened forms of the pathogen, or purified highly immunogenic components, such as viral envelope proteins. Smallpox was the first disease for which a vaccine was produced, by Edward Jenner in 1796.

Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases and can also ameliorate the symptoms of infection. When a sufficiently high proportion of a population has been vaccinated, herd immunity results. Widespread immunity due to mass vaccination is largely responsible for the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the elimination of diseases such as polio from much of the world. Since their inception, vaccination efforts have met with objections on scientific, ethical, political, medical safety and religious grounds, and the World Health Organization considers vaccine hesitancy an important threat to global health.

Selected outbreak

The 2009 flu pandemic was an influenza pandemic first recognised in Mexico City in March 2009 and declared over in August 2010. It involved a novel strain of H1N1 influenza virus with genes from five different viruses, which resulted when a previous triple reassortment of avian, swine and human influenza viruses further combined with a Eurasian swine influenza virus, leading to the term "swine flu" being used for the pandemic. It was the second pandemic to involve an H1N1 strain, the first being the 1918 "Spanish flu" pandemic.

The global infection rate was estimated as 11–21%. This pandemic strain was less lethal than previous ones, killing about 0.01–0.03% of those infected, compared with 2–3% for Spanish flu. Most experts agree that at least 284,500 people died, mainly in Africa and Southeast Asia – comparable with the normal seasonal influenza fatalities of 290,000–650,000 – leading to claims that the World Health Organization had exaggerated the danger.

Selected quotation

| “ | There are more viruses on Earth than stars in the universe. | ” |

Recommended articles

Viruses & Subviral agents: bat virome • elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus • HIV • introduction to viruses![]() • Playa de Oro virus • poliovirus • prion • rotavirus

• Playa de Oro virus • poliovirus • prion • rotavirus![]() • virus

• virus![]()

Diseases: colony collapse disorder • common cold • croup • dengue fever![]() • gastroenteritis • Guillain–Barré syndrome • hepatitis B • hepatitis C • hepatitis E • herpes simplex • HIV/AIDS • influenza

• gastroenteritis • Guillain–Barré syndrome • hepatitis B • hepatitis C • hepatitis E • herpes simplex • HIV/AIDS • influenza![]() • meningitis

• meningitis![]() • myxomatosis • polio

• myxomatosis • polio![]() • pneumonia • shingles • smallpox

• pneumonia • shingles • smallpox

Epidemiology & Interventions: 2007 Bernard Matthews H5N1 outbreak • Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations • Disease X • 2009 flu pandemic • HIV/AIDS in Malawi • polio vaccine • Spanish flu • West African Ebola virus epidemic

Virus–Host interactions: antibody • host • immune system![]() • parasitism • RNA interference

• parasitism • RNA interference![]()

Methodology: metagenomics

Social & Media: And the Band Played On • Contagion • "Flu Season" • Frank's Cock![]() • Race Against Time: Searching for Hope in AIDS-Ravaged Africa

• Race Against Time: Searching for Hope in AIDS-Ravaged Africa![]() • social history of viruses

• social history of viruses![]() • "Steve Burdick" • "The Time Is Now" • "What Lies Below"

• "Steve Burdick" • "The Time Is Now" • "What Lies Below"

People: Brownie Mary • Macfarlane Burnet![]() • Bobbi Campbell • Aniru Conteh • people with hepatitis C

• Bobbi Campbell • Aniru Conteh • people with hepatitis C![]() • HIV-positive people

• HIV-positive people![]() • Bette Korber • Henrietta Lacks • Linda Laubenstein • Barbara McClintock

• Bette Korber • Henrietta Lacks • Linda Laubenstein • Barbara McClintock![]() • poliomyelitis survivors

• poliomyelitis survivors![]() • Joseph Sonnabend • Eli Todd • Ryan White

• Joseph Sonnabend • Eli Todd • Ryan White![]()

Selected virus

Henipaviruses are a genus of RNA viruses in the Paramyxoviridae family. The variably shaped, 40–600 nm diameter, enveloped capsid contains a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA genome of 18.2 kb, with six genes. The cellular receptor is in the ephrin family. The natural hosts are predominantly bats, mainly the Pteropus genus of megabats (flying foxes) and some microbats. Bats infected with Hendra virus develop viraemia and shed virus in urine, faeces and saliva for around a week, but show no signs of disease. Henipaviruses can also infect humans and livestock, causing severe disease with high mortality, making the group a zoonootic disease. Transmission to humans sometimes occurs via an intermediate domestic animal host.

The first henipavirus, Hendra virus, was discovered in 1994 as the cause of an outbreak in horses in Brisbane, Australia. Nipah virus was identified a few years later in Malaysia as the cause of an outbreak in pigs. Three further species have since been recognised: Cedar and Kumasi viruses in bats, and Mòjiāng virus in rodents. Their emergence as human pathogens has been linked to increased contact between bats and humans. Human disease has been confined to Australia and Asia, but members of the genus have also been found in African bats. A veterinary vaccine against Hendra virus is available but no human vaccine has been licensed.

Did you know?

- ...that modified mRNA (mRNA translation depicted) is a key technology in the Moderna and BioNTech/Pfizer vaccines against COVID-19?

- ...that Derrick Tovey recognised early cases of smallpox during an outbreak in Bradford in 1962?

- ...that Nkosi's Haven is a South African care centre created to address HIV-related discrimination, including the separation of infected mothers from their children?

- ...that American physician Max C. Starkloff used social distancing to fight the 1918 flu pandemic in St. Louis?

- ...that following his research for Epidemiology in Country Practice, William Pickles observed that "studies in epidemiology sometimes reveal romances"?

Selected biography

Randy Shilts (8 August 1951 – 17 February 1994) was an American journalist, author and AIDS activist. The first openly gay reporter for a mainstream US newspaper, Shilts covered the unfolding story of AIDS and its medical, social, and political ramifications from the first reports of the disease in 1981. New York University's journalism department later ranked his 1981–85 AIDS reporting in the top fifty works of American journalism of the 20th century. His extensively researched account of the early days of the epidemic in the US, And the Band Played On Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic, first published in 1987, brought him national fame. The book won the Stonewall Book Award and was made into an award-winning film. Shilts saw himself as a literary journalist in the tradition of Truman Capote and Norman Mailer. His writing has a powerful narrative drive and interweaves personal stories with political and social reporting.

He received the 1988 Outstanding Author award from the American Society of Journalists and Authors, the 1990 Mather Lectureship at Harvard University, and the 1993 Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists' Association. He died of AIDS in 1994.

In this month

February 1939: First virology journal, Archiv für die gesamte Virusforschung, appeared

8 February 1951: Establishment of the HeLa cell line from a cervical carcinoma biopsy, the first immortal human cell line

12 February 1892: Dmitri Ivanovsky (pictured) demonstrated transmission of tobacco mosaic disease by extracts filtered through Chamberland filters; sometimes considered the beginning of virology

19 February 1966: Prion disease kuru shown to be transmissible

23 February 2018: Baloxavir marboxil, the first anti-influenza agent to target the cap-dependent endonuclease activity of the viral polymerase, approved in Japan

27 February 2005: H1N1 influenza strain resistant to oseltamivir reported in a human patient

24 February 1977: Phi X 174 sequenced by Fred Sanger and coworkers, the first virus and the first DNA genome to be sequenced

28 February 1998: Publication of Andrew Wakefield's Lancet paper, subsequently discredited, linking the MMR vaccine with autism, which started the MMR vaccine controversy

Selected intervention

Nevirapine (also Viramune) is an antiretroviral drug used in the treatment of HIV/AIDS caused by HIV-1. It was the first non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor to be licensed, which occurred in 1996. Like nucleoside inhibitors, nevirapine inhibits HIV's reverse transcriptase enzyme, which copies the viral RNA into DNA and is essential for its replication. Unlike nucleoside inhibitors, it binds not in the enzyme's active site but in a nearby hydrophobic pocket, causing a conformational change in the enzyme that prevents it from functioning. Mutations in the pocket generate resistance to nevirapine, which develops rapidly unless viral replication is completely suppressed. The drug is therefore only used together with other anti-HIV drugs in combination therapy. The HIV-2 reverse transcriptase has a different pocket structure, rendering it inherently resistant to nevirapine and other first-generation NNRTIs. A single dose of nevirapine is a cost-effective way to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV, and has been recommended by the World Health Organization for use in resource-poor settings. Other protocols are recommended in the United States. Rash is the most common adverse event associated with the drug.

Subcategories

Subcategories of virology:

Topics

Things to do

- Comment on what you like and dislike about this portal

- Join the Viruses WikiProject

- Tag articles on viruses and virology with the project banner by adding ((WikiProject Viruses)) to the talk page

- Assess unassessed articles against the project standards

- Create requested pages: red-linked viruses | red-linked virus genera

- Expand a virus stub into a full article, adding images, citations, references and taxoboxes, following the project guidelines

- Create a new article (or expand an old one 5-fold) and nominate it for the main page Did You Know? section

- Improve a B-class article and nominate it for Good Article

or Featured Article

or Featured Article status

status - Suggest articles, pictures, interesting facts, events and news to be featured here on the portal

WikiProjects & Portals

WikiProject Viruses

Related WikiProjects

WikiProject Viruses

Related WikiProjects

Medicine • Microbiology • Molecular & Cellular Biology • Veterinary Medicine

Related PortalsAssociated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikispecies

Directory of species -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus