Tristan Tzara | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Tristan Tzara, by Robert Delaunay (1923) | |

| Born | Samuel (Samy) Rosenstock 28 April 1896 Moinești, Romania |

| Died | 25 December 1963 (aged 67) Paris, France |

| Pen name | S. Samyro, Tristan, Tristan Ruia, Tristan Țara, Tr. Tzara |

| Occupation | Poet, essayist, journalist, playwright, performance artist, composer, film director, politician, diplomat |

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Period | 1912–1963 |

| Genre | Lyric poetry, epic poetry, free verse, prose poetry, parody, satire, utopian fiction |

| Subject | Art criticism, literary criticism, social criticism |

| Literary movement | Symbolism Avant-garde Dada Surrealism |

| Signature | |

Tristan Tzara (French: [tʁistɑ̃ dzaʁa]; Romanian: [trisˈtan ˈt͡sara]; born Samuel or Samy Rosenstock, also known as S. Samyro; 28 April [O.S. 16 April] 1896[1] – 25 December 1963) was a Romanian avant-garde poet, essayist and performance artist. Also active as a journalist, playwright, literary and art critic, composer and film director, he was known best for being one of the founders and central figures of the anti-establishment Dada movement. Under the influence of Adrian Maniu, the adolescent Tzara became interested in Symbolism and co-founded the magazine Simbolul with Ion Vinea (with whom he also wrote experimental poetry) and painter Marcel Janco.

During World War I, after briefly collaborating on Vinea's Chemarea, he joined Janco in Switzerland. There, Tzara's shows at the Cabaret Voltaire and Zunfthaus zur Waag, as well as his poetry and art manifestos, became a main feature of early Dadaism. His work represented Dada's nihilistic side, in contrast with the more moderate approach favored by Hugo Ball.

After moving to Paris in 1919, Tzara, by then one of the "presidents of Dada", joined the staff of Littérature magazine, which marked the first step in the movement's evolution toward Surrealism. He was involved in the major polemics which led to Dada's split, defending his principles against André Breton and Francis Picabia, and, in Romania, against the eclectic modernism of Vinea and Janco. This personal vision on art defined his Dadaist plays The Gas Heart (1921) and Handkerchief of Clouds (1924). A forerunner of automatist techniques, Tzara eventually aligned himself with Breton's Surrealism, and under its influence wrote his celebrated utopian poem "The Approximate Man".

During the final part of his career, Tzara combined his humanist and anti-fascist perspective with a communist vision, joining the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War and the French Resistance during World War II, and serving a term in the National Assembly. Having spoken in favor of liberalization in the People's Republic of Hungary just before the Revolution of 1956, he distanced himself from the French Communist Party, of which he was by then a member. In 1960, he was among the intellectuals who protested against French actions in the Algerian War.

Tristan Tzara was an influential author and performer, whose contribution is credited with having created a connection from Cubism and Futurism to the Beat Generation, Situationism and various currents in rock music. The friend and collaborator of many modernist figures, he was the lover of dancer Maja Kruscek in his early youth and was later married to Swedish artist and poet Greta Knutson.

S. Samyro, a partial anagram of Samy Rosenstock, was used by Tzara from his debut and throughout the early 1910s.[2] A number of undated writings, which he probably authored as early as 1913, bear the signature Tristan Ruia, and, in summer of 1915, he was signing his pieces with the name Tristan.[3][4]

In the 1960s, Rosenstock's collaborator and later rival Ion Vinea claimed that he was responsible for coining the Tzara part of his pseudonym in 1915.[3] Vinea also stated that Tzara wanted to keep Tristan as his adopted first name, and that this choice had later attracted him the "infamous pun" Triste Âne Tzara (French for "Sad Donkey Tzara").[3] This version of events is uncertain, as manuscripts show that the writer may have already been using the full name, as well as the variations Tristan Țara and Tr. Tzara, in 1913–1914 (although there is a possibility that he was signing his texts long after committing them to paper).[5]

In 1972, art historian Serge Fauchereau, based on information received from Colomba, the wife of avant-garde poet Ilarie Voronca, recounted that Tzara had explained his chosen name was a pun in Romanian, trist în țară, meaning "sad in the country"; Colomba Voronca was also dismissing rumors that Tzara had selected Tristan as a tribute to poet Tristan Corbière or to Richard Wagner's Tristan und Isolde opera.[6] Samy Rosenstock legally adopted his new name in 1925, after filing a request with Romania's Ministry of the Interior.[6] The French pronunciation of his name has become commonplace in Romania, where it replaces its more natural reading as țara ("the land", Romanian pronunciation: [ˈt͡sara]).[7]

Tzara was born in Moinești, Bacău County, in the historical region of Western Moldavia. His parents were Jewish Romanians who reportedly spoke Yiddish as their first language;[8] his father Filip and grandfather Ilie were entrepreneurs in the forestry business.[9][10] Tzara's mother was Emilia Rosenstock (née Zibalis).[10] Owing to the Romanian Kingdom's discrimination laws, the Rosenstocks were not emancipated, and thus Tzara was not a full citizen of the country until after 1918.[9]

He moved to Bucharest at the age of eleven, and attended the Schemitz-Tierin boarding school.[9] It is believed that the young Tzara completed his secondary education at a state-run high school, which is identified as the Saint Sava National College[9] or as the Sfântul Gheorghe High School.[11] In October 1912, when Tzara was aged sixteen, he joined his friends Vinea and Marcel Janco in editing Simbolul. Reputedly, Janco and Vinea provided the funds.[12] Like Vinea, Tzara was also close to their young colleague Jacques G. Costin, who was later his self-declared promoter and admirer.[13]

Despite their young age, the three editors were able to attract collaborations from established Symbolist authors, active within Romania's own Symbolist movement. Alongside their close friend and mentor Adrian Maniu (an Imagist who had been Vinea's tutor),[14] they included N. Davidescu, Alfred Hefter-Hidalgo, Emil Isac, Claudia Millian, Ion Minulescu, I. M. Rașcu, Eugeniu Sperantia, Al. T. Stamatiad, Eugeniu Ștefănescu-Est, and Constantin T. Stoika, as well as journalist and lawyer Poldi Chapier.[15] In its inaugural issue, the journal even printed a poem by one of the leading figures in Romanian Symbolism, Alexandru Macedonski.[15] Simbolul also featured illustrations by Maniu, Millian and Iosif Iser.[16]

Although the magazine ceased print in December 1912, it played an important part in shaping Romanian literature of the period. Literary historian Paul Cernat sees Simbolul as a main stage in Romania's modernism, and credits it with having brought about the first changes from Symbolism to the radical avant-garde.[17] Also according to Cernat, the collaboration between Samyro, Vinea and Janco was an early instance of literature becoming "an interface between arts", which had for its contemporary equivalent the collaboration between Iser and writers such as Ion Minulescu and Tudor Arghezi.[18] Although Maniu parted with the group and sought a change in style which brought him closer to traditionalist tenets, Tzara, Janco and Vinea continued their collaboration. Between 1913 and 1915, they were frequently vacationing together, either on the Black Sea coast or at the Rosenstock family property in Gârceni, Vaslui County; during this time, Vinea and Samyro wrote poems with similar themes and alluding to one another.[19]

Tzara's career changed course between 1914 and 1916, during a period when the Romanian Kingdom kept out of World War I. In autumn 1915, as founder and editor of the short-lived journal Chemarea, Vinea published two poems by his friend, the first printed works to bear the signature Tristan Tzara.[20] At the time, the young poet and many of his friends were adherents of an anti-war and anti-nationalist current, which progressively accommodated anti-establishment messages.[21] Chemarea, which was a platform for this agenda and again attracted collaborations from Chapier, may also have been financed by Tzara and Vinea.[12] According to Romanian avant-garde writer Claude Sernet, the journal was "totally different from everything that had been printed in Romania before that moment."[22] During the period, Tzara's works were sporadically published in Hefter-Hidalgo's Versuri și Proză, and, in June 1915, Constantin Rădulescu-Motru's Noua Revistă Română published Samyro's known poem Verișoară, fată de pension ("Little Cousin, Boarding School Girl").[2]

Tzara had enrolled at the University of Bucharest in 1914, studying mathematics and philosophy, but did not graduate.[9][23] In autumn 1915, he left Romania for Zürich, in neutral Switzerland. Janco, together with his brother Jules Janco, had settled there a few months before, and was later joined by his other brother, Georges Janco.[24] Tzara, who may have applied to the Faculty of Philosophy at the local university,[9][25] shared lodging with Marcel Janco, who was a student at the Technische Hochschule, in the Altinger Guest House[26] (by 1918, Tzara had moved to the Limmatquai Hotel).[27] His departure from Romania, like that of the Janco brothers, may have been in part a pacifist political statement.[28] After settling in Switzerland, the young poet almost completely discarded Romanian as his language of expression, writing most of his subsequent works in French.[23][29] The poems he had written before, which were the result of poetic dialogues between him and his friend, were left in Vinea's care.[30] Most of these pieces were first printed only in the interwar period.[23][31]

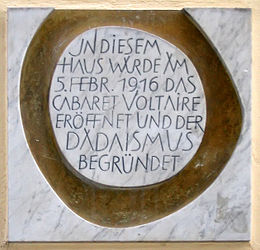

It was in Zürich that the Romanian group met with the German Hugo Ball, an anarchist poet and pianist, and his young wife Emmy Hennings, a music hall performer. In February 1916, Ball had rented the Cabaret Voltaire from its owner, Jan Ephraim, and intended to use the venue for performance art and exhibits.[32] Hugo Ball recorded this period, noting that Tzara and Marcel Janco, like Hans Arp, Arthur Segal, Otto van Rees, and Max Oppenheimer "readily agreed to take part in the cabaret".[33] According to Ball, among the performances of songs mimicking or taking inspiration from various national folklores, "Herr Tristan Tzara recited Rumanian poetry."[34] In late March, Ball recounted, the group was joined by German writer and drummer Richard Huelsenbeck.[33] He was soon after involved in Tzara's "simultaneist verse" performance, "the first in Zürich and in the world", also including renditions of poems by two promoters of Cubism, Fernand Divoire and Henri Barzun.[35]

It was in this milieu that Dada was born, at some point before May 1916, when a publication of the same name first saw print. The story of its establishment was the subject of a disagreement between Tzara and his fellow writers. Cernat believes that the first Dadaist performance took place as early as February, when the nineteen-year-old Tzara, wearing a monocle, entered the Cabaret Voltaire stage singing sentimental melodies and handing paper wads to his "scandalized spectators", leaving the stage to allow room for masked actors on stilts, and returning in clown attire.[36] The same type of performances took place at the Zunfthaus zur Waag beginning in summer 1916, after the Cabaret Voltaire was forced to close down.[37]

According to music historian Bernard Gendron, for as long as it lasted, "the Cabaret Voltaire was dada. There was no alternative institution or site that could disentangle 'pure' dada from its mere accompaniment [...] nor was any such site desired."[38] Other opinions link Dada's beginnings with much earlier events, including the experiments of Alfred Jarry, André Gide, Christian Morgenstern, Jean-Pierre Brisset, Guillaume Apollinaire, Jacques Vaché, Marcel Duchamp, and Francis Picabia.[39]

In the first of the movement's manifestos, Ball wrote: "[The booklet] is intended to present to the Public the activities and interests of the Cabaret Voltaire, which has as its sole purpose to draw attention, across the barriers of war and nationalism, to the few independent spirits who live for other ideals. The next objective of the artists who are assembled here is to publish a revue internationale [French for 'international magazine']."[40] Ball completed his message in French, and the paragraph translates as: "The magazine shall be published in Zürich and shall carry the name 'Dada' ('Dada'). Dada Dada Dada Dada."[40] The view according to which Ball had created the movement was notably supported by writer Walter Serner, who directly accused Tzara of having abused Ball's initiative.[41]

A secondary point of contention between the founders of Dada regarded the paternity for the movement's name, which, according to visual artist and essayist Hans Richter, was first adopted in print in June 1916.[42] Ball, who claimed authorship and stated that he picked the word randomly from a dictionary, indicated that it stood for both the French-language equivalent of "hobby horse" and a German-language term reflecting the joy of children being rocked to sleep.[43] Tzara himself declined interest in the matter, but Marcel Janco credited him with having coined the term.[44] Dada manifestos, written or co-authored by Tzara, record that the name shares its form with various other terms, including a word used in the Kru languages of West Africa to designate the tail of a sacred cow; a toy and the name for "mother" in an unspecified Italian dialect; and the double affirmative in Romanian and in various Slavic languages.[45]

Before the end of the war, Tzara had assumed a position as Dada's main promoter and manager, helping the Swiss group establish branches in other European countries.[25][46] This period also saw the first conflict within the group: citing irreconcilable differences with Tzara, Ball left the group.[47] With his departure, Gendron argues, Tzara was able to move Dada vaudeville-like performances into more of "an incendiary and yet jocularly provocative theater."[48]

He is often credited with having inspired many young modernist authors from outside Switzerland to affiliate with the group, in particular the Frenchmen Louis Aragon, André Breton, Paul Éluard, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and Philippe Soupault.[4][49] Richter, who also came into contact with Dada at this stage in its history, notes that these intellectuals often had a "very cool and distant attitude to this new movement" before being approached by the Romanian author.[49] In June 1916, he began editing and managing the periodical Dada as a successor of the short-lived magazine Cabaret Voltaire—Richter describes his "energy, passion and talent for the job", which he claims satisfied all Dadaists.[50] He was at the time the lover of Maja Kruscek, who was a student of Rudolf Laban; in Richter's account, their relationship was always tottering.[51]

As early as 1916, Tristan Tzara took distance from the Italian Futurists, rejecting the militarist and proto-fascist stance of their leader Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.[52] Richter notes that, by then, Dada had replaced Futurism as the leader of modernism, while continuing to build on its influence: "we had swallowed Futurism—bones, feathers and all. It is true that in the process of digestion all sorts of bones and feathers had been regurgitated."[49] Despite this and the fact that Dada did not make any gains in Italy, Tzara could count poets Giuseppe Ungaretti and Alberto Savinio, painters Gino Cantarelli and Aldo Fiozzi, as well as a few other Italian Futurists, among the Dadaists.[53] Among the Italian authors supporting Dadaist manifestos and rallying with the Dada group was the poet, painter and in the future a fascist racial theorist Julius Evola, who became a personal friend of Tzara.[54]

The next year, Tzara and Ball opened the Galerie Dada permanent exhibit, through which they set contacts with the independent Italian visual artist Giorgio de Chirico and with the German Expressionist journal Der Sturm, all of whom were described as "fathers of Dada".[55] During the same months, and probably owing to Tzara's intervention, the Dada group organized a performance of Sphinx and Strawman, a puppet play by the Austro-Hungarian Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka, whom he advertised as an example of "Dada theater".[56] He was also in touch with Nord-Sud, the magazine of French poet Pierre Reverdy (who sought to unify all avant-garde trends),[4] and contributed articles on African art to both Nord-Sud and Pierre Albert-Birot's SIC magazine.[57] In early 1918, through Huelsenbeck, Zürich Dadaists established contacts with their more explicitly left-wing disciples in the German Empire — George Grosz, John Heartfield, Johannes Baader, Kurt Schwitters, Walter Mehring, Raoul Hausmann, Carl Einstein, Franz Jung, and Heartfield's brother Wieland Herzfelde.[58] With Breton, Soupault and Aragon, Tzara traveled Cologne, where he became familiarized with the elaborate collage works of Schwitters and Max Ernst, which he showed to his colleagues in Switzerland.[59] Huelsenbeck nonetheless declined to Schwitters membership in Berlin Dada.[60]

As a result of his campaigning, Tzara created a list of so-called "Dada presidents", who represented various regions of Europe. According to Hans Richter, it included, alongside Tzara, figures ranging from Ernst, Arp, Baader, Breton and Aragon to Kruscek, Evola, Rafael Lasso de la Vega, Igor Stravinsky, Vicente Huidobro, Francesco Meriano and Théodore Fraenkel.[61] Richter notes: "I'm not sure if all the names who appear here would agree with the description."[62]

The shows Tzara staged in Zürich often turned into scandals or riots, and he was in permanent conflict with the Swiss law enforcers.[63] Hans Richter speaks of a "pleasure of letting fly at the bourgeois, which in Tristan Tzara took the form of coldly (or hotly) calculated insolence" (see Épater la bourgeoisie).[64] In one instance, as part of a series of events in which Dadaists mocked established authors, Tzara and Arp falsely publicized that they were going to fight a duel in Rehalp, near Zürich, and that they were going to have the popular novelist Jakob Christoph Heer for their witness.[65] Richter also reports that his Romanian colleague profited from Swiss neutrality to play the Allies and Central Powers against each other, obtaining art works and funds from both, making use of their need to stimulate their respective propaganda efforts.[66] While active as a promoter, Tzara also published his first volume of collected poetry, the 1918 Vingt-cinq poèmes ("Twenty-five Poems").[67]

A major event took place in autumn 1918, when Francis Picabia, who was then publisher of 391 magazine and a distant Dada affiliate, visited Zürich and introduced his colleagues there to his nihilistic views on art and reason.[68] In the United States, Picabia, Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp had earlier set up their own version of Dada. This circle, based in New York City, sought affiliation with Tzara's only in 1921, when they jokingly asked him to grant them permission to use "Dada" as their own name (to which Tzara replied: "Dada belongs to everybody").[69] The visit was credited by Richter with boosting the Romanian author's status, but also with making Tzara himself "switch suddenly from a position of balance between art and anti-art into the stratospheric regions of pure and joyful nothingness."[70] The movement subsequently organized its last major Swiss show, held at the Saal zur Kaufleutern, with choreography by Susanne Perrottet, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and with the participation of Käthe Wulff, Hans Heusser, Tzara, Hans Richter and Walter Serner.[71] It was there that Serner read from his 1918 essay, whose very title advocated Letzte Lockerung ("Final Dissolution"): this part is believed to have caused the subsequent mêlée, during which the public attacked the performers and succeeded in interrupting, but not canceling, the show.[72]

Following the November 1918 Armistice with Germany, Dada's evolution was marked by political developments. In October 1919, Tzara, Arp and Otto Flake began publishing Der Zeltweg, a journal aimed at further popularizing Dada in a post-war world were the borders were again accessible.[73] Richter, who admits that the magazine was "rather tame", also notes that Tzara and his colleagues were dealing with the impact of communist revolutions, in particular the October Revolution and the German revolts of 1918, which "had stirred men's minds, divided men's interests and diverted energies in the direction of political change."[73] The same commentator, however, dismisses those accounts which, he believes, led readers to believe that Der Zeltweg was "an association of revolutionary artists."[73] According to one account rendered by historian Robert Levy, Tzara shared company with a group of Romanian communist students, and, as such, may have met with Ana Pauker, who was later one of the Romanian Communist Party's most prominent activists.[74]

Arp and Janco drifted away from the movement ca. 1919, when they created the Constructivist-inspired workshop Das Neue Leben.[75] In Romania, Dada was awarded an ambiguous reception from Tzara's former associate Vinea. Although he was sympathetic to its goals, treasured Hugo Ball and Hennings and promised to adapt his own writings to its requirements, Vinea cautioned Tzara and the Jancos in favor of lucidity.[76] When Vinea submitted his poem Doleanțe ("Grievances") to be published by Tzara and his associates, he was turned down, an incident which critics attribute to a contrast between the reserved tone of the piece and the revolutionary tenets of Dada.[77]

In late 1919, Tristan Tzara left Switzerland to join Breton, Soupault and Claude Rivière in editing the Paris-based magazine Littérature.[25][78] Already a mentor for the French avant-garde, he was, according to Hans Richter, perceived as an "Anti-Messiah" and a "prophet".[79] Reportedly, Dada mythology had it that he entered the French capital in a snow-white or lilac-colored car, passing down Boulevard Raspail through a triumphal arch made from his own pamphlets, being greeted by cheering crowds and a fireworks display.[79] Richter dismisses this account, indicating that Tzara actually walked from Gare de l'Est to Picabia's home, without anyone expecting him to arrive.[79]

He is often described as the main figure in the Littérature circle, and credited with having more firmly set its artistic principles in the line of Dada.[25][80] When Picabia began publishing a new series of 391 in Paris, Tzara seconded him and, Richter says, produced issues of the magazine "decked out [...] in all the colors of Dada."[57] He was also issuing his Dada magazine, printed in Paris but using the same format, renaming it Bulletin Dada and later Dadaphone.[81] At around that time, he met American author Gertrude Stein, who wrote about him in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas,[82] and the artist couple Robert and Sonia Delaunay (with whom he worked in tandem for "poem-dresses" and other simultaneist literary pieces).[83]

Tzara became involved in a number of Dada experiments, on which he collaborated with Breton, Aragon, Soupault, Picabia or Paul Éluard.[4][84][85] Other authors who came into contact with Dada at that stage were Jean Cocteau, Paul Dermée and Raymond Radiguet.[86] The performances staged by Dada were often meant to popularize its principles, and Dada continued to draw attention on itself by hoaxes and false advertising, announcing that the Hollywood film star Charlie Chaplin was going to appear on stage at its show,[48] or that its members were going to have their heads shaved or their hair cut off on stage.[87] In another instance, Tzara and his associates lectured at the Université populaire in front of industrial workers, who were reportedly less than impressed.[88] Richter believes that, ideologically, Tzara was still in tribute to Picabia's nihilistic and anarchic views (which made the Dadaists attack all political and cultural ideologies), but that this also implied a measure of sympathy for the working class.[88]

Dada activities in Paris culminated in the March 1920 variety show at the Théâtre de l'Œuvre, which featured readings from Breton, Picabia, Dermée and Tzara's earlier work, La Première aventure céleste de M. Antipyrine ("The First Heavenly Adventure of Mr. Antipyrine").[89] Tzara's melody, Vaseline symphonique ("Symphonic Vaseline"), which required ten or twenty people to shout "cra" and "cri" on a rising scale, was also performed.[90] A scandal erupted when Breton read Picabia's Manifeste cannibale ("Cannibal Manifesto"), lashing out at the audience and mocking them, to which they answered by aiming rotten fruit at the stage.[91]

The Dada phenomenon was only noticed in Romania beginning in 1920, and its overall reception was negative. Traditionalist historian Nicolae Iorga, Symbolist promoter Ovid Densusianu, the more reserved modernists Camil Petrescu and Benjamin Fondane all refused to accept it as a valid artistic manifestation.[92] Although he rallied with tradition, Vinea defended the subversive current in front of more serious criticism, and rejected the widespread rumor that Tzara had acted as an agent of influence for the Central Powers during the war.[93] Eugen Lovinescu, editor of Sburătorul and one of Vinea's rivals on the modernist scene, acknowledged the influence exercised by Tzara on the younger avant-garde authors, but analyzed his work only briefly, using as an example one of his pre-Dada poems, and depicting him as an advocate of literary "extremism".[94]

By 1921, Tzara had become involved in conflicts with other figures in the movement, whom he claimed had parted with the spirit of Dada.[95] He was targeted by the Berlin-based Dadaists, in particular by Huelsenbeck and Serner, the former of whom was also involved in a conflict with Raoul Hausmann over leadership status.[41] According to Richter, tensions between Breton and Tzara had surfaced in 1920, when Breton first made known his wish to do away with musical performances altogether and alleged that the Romanian was merely repeating himself.[96] The Dada shows themselves were by then such common occurrences that audiences expected to be insulted by the performers.[67]

A more serious crisis occurred in May, when Dada organized a mock trial of Maurice Barrès, whose early affiliation with the Symbolists had been shadowed by his antisemitism and reactionary stance: Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes was the prosecutor, Aragon and Soupault the defense attorneys, with Tzara, Ungaretti, Benjamin Péret and others as witnesses (a mannequin stood in for Barrès).[97] Péret immediately upset Picabia and Tzara by refusing to make the trial an absurd one, and by introducing a political subtext with which Breton nevertheless agreed.[98] In June, Tzara and Picabia clashed with each other, after Tzara expressed an opinion that his former mentor was becoming too radical.[99] During the same season, Breton, Arp, Ernst, Maja Kruschek and Tzara were in Austria, at Imst, where they published their last manifesto as a group, Dada au grand air ("Dada in the Open Air") or Der Sängerkrieg in Tirol ("The Battle of the Singers in Tyrol").[100] Tzara also visited Czechoslovakia, where he reportedly hoped to gain adherents to his cause.[101]

Also in 1921, Ion Vinea wrote an article for the Romanian newspaper Adevărul, arguing that the movement had exhausted itself (although, in his letters to Tzara, he continued to ask his friend to return home and spread his message there).[102] After July 1922, Marcel Janco rallied with Vinea in editing Contimporanul, which published some of Tzara's earliest poems but never offered space to any Dadaist manifesto.[103] Reportedly, the conflict between Tzara and Janco had a personal note: Janco later mentioned "some dramatic quarrels" between his colleague and him.[104] They avoided each other for the rest of their lives and Tzara even struck out the dedications to Janco from his early poems.[105] Julius Evola also grew disappointed by the movement's total rejection of tradition and began his personal search for an alternative, pursuing a path which later led him to esotericism and fascism.[54]

Tzara was openly attacked by Breton in a February 1922 article for Le Journal de Peuple, where the Romanian writer was denounced as "an impostor" avid for "publicity".[106] In March, Breton initiated the Congress for the Determination and Defense of the Modern Spirit. The French writer used the occasion to strike out Tzara's name from among the Dadaists, citing in his support Dada's Huelsenbeck, Serner, and Christian Schad.[107] Basing his statement on a note supposedly authored by Huelsenbeck, Breton also accused Tzara of opportunism, claiming that he had planned wartime editions of Dada works in such a manner as not to upset actors on the political stage, making sure that German Dadaists were not made available to the public in countries subject to the Supreme War Council.[107] Tzara, who attended the Congress only as a means to subvert it,[108] responded to the accusations the same month, arguing that Huelsenbeck's note was fabricated and that Schad had not been one of the original Dadaists.[107] Rumors reported much later by American writer Brion Gysin had it that Breton's claims also depicted Tzara as an informer for the Prefecture of Police.[109]

In May 1922, Dada staged its own funeral.[110] According to Hans Richter, the main part of this took place in Weimar, where the Dadaists attended a festival of the Bauhaus art school, during which Tzara proclaimed the elusive nature of his art: "Dada is useless, like everything else in life. [...] Dada is a virgin microbe which penetrates with the insistence of air into all those spaces that reason has failed to fill with words and conventions."[111]

In "The Bearded Heart" manifesto a number of artists backed the marginalization of Breton in support of Tzara. Alongside Cocteau, Arp, Ribemont-Dessaignes, and Éluard, the pro-Tzara faction included Erik Satie, Theo van Doesburg, Serge Charchoune, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Marcel Duchamp, Ossip Zadkine, Jean Metzinger, Ilia Zdanevich, and Man Ray.[112] During an associated soirée, Evening of the Bearded Heart, which began on 6 July 1923, Tzara presented a re-staging of his play The Gas Heart (which had been first performed two years earlier to howls of derision from its audience), for which Sonia Delaunay designed the costumes.[83] Breton interrupted its performance and reportedly fought with several of his former associates and broke furniture, prompting a theatre riot that only the intervention of the police halted.[113] Dada's vaudeville declined in importance and disappeared altogether after that date.[114]

Picabia took Breton's side against Tzara,[115] and replaced the staff of his 391, enlisting collaborations from Clément Pansaers and Ezra Pound.[116] Breton marked the end of Dada in 1924, when he issued the first Surrealist Manifesto. Richter suggests that "Surrealism devoured and digested Dada."[110] Tzara distanced himself from the new trend, disagreeing with its methods and, increasingly, with its politics.[25][67][84][117] In 1923, he and a few other former Dadaists collaborated with Richter and the Constructivist artist El Lissitzky on the magazine G,[118] and, the following year, he wrote pieces for the Yugoslav-Slovenian magazine Tank (edited by Ferdinand Delak).[119]

Tzara continued to write, becoming more seriously interested in the theater. In 1924, he published and staged the play Handkerchief of Clouds, which was soon included in the repertoire of Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes.[120] He also collected his earlier Dada texts as the Seven Dada Manifestos. Marxist thinker Henri Lefebvre reviewed them enthusiastically; he later became one of the author's friends.[121]

In Romania, Tzara's work was partly recuperated by Contimporanul, which notably staged public readings of his works during the international art exhibit it organized in 1924, and again during the "new art demonstration" of 1925.[122] In parallel, the short-lived magazine Integral, where Ilarie Voronca and Ion Călugăru were the main animators, took significant interest in Tzara's work.[123] In a 1927 interview with the publication, he voiced his opposition to the Surrealist group's adoption of communism, indicating that such politics could only result in a "new bourgeoisie" being created, and explaining that he had opted for a personal "permanent revolution", which would preserve "the holiness of the ego".[124]

In 1925, Tristan Tzara was in Stockholm, where he married Greta Knutson, with whom he had a son, Christophe (born 1927).[4] A former student of painter André Lhote, she was known for her interest in phenomenology and abstract art.[125] Around the same period, with funds from Knutson's inheritance, Tzara commissioned Austrian architect Adolf Loos, a former representative of the Vienna Secession whom he had met in Zürich, to build him a house in Paris.[4] The rigidly functionalist Maison Tristan Tzara, built in Montmartre, was designed following Tzara's specific requirements and decorated with samples of African art.[4] It was Loos' only major contribution in his Parisian years.[4]

In 1929, he reconciled with Breton, and sporadically attended the Surrealists' meetings in Paris.[67][84] The same year, he issued the poetry book De nos oiseaux ("Of Our Birds").[67] This period saw the publication of The Approximate Man (1931), alongside the volumes L'Arbre des voyageurs ("The Travelers' Tree", 1930), Où boivent les loups ("Where Wolves Drink", 1932), L'Antitête ("The Antihead", 1933) and Grains et issues ("Seed and Bran", 1935).[84] By then, it was also announced that Tzara had started work on a screenplay.[126] In 1930, he directed and produced a cinematic version of Le Cœur à barbe, starring Breton and other leading Surrealists.[127] Five years later, he signed his name to The Testimony against Gertrude Stein, published by Eugene Jolas's magazine transition in reply to Stein's memoir The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, in which he accused his former friend of being a megalomaniac.[128]

The poet became involved in further developing Surrealist techniques, and, together with Breton and Valentine Hugo, drew one of the better-known examples of "exquisite corpses".[129] Tzara also prefaced a 1934 collection of Surrealist poems by his friend René Char, and the following year he and Greta Knutson visited Char in L'Isle-sur-la-Sorgue.[130] Tzara's wife was also affiliated with the Surrealist group at around the same time.[4][125] This association ended when she parted with Tzara late in the 1930s.[4][125]

At home, Tzara's works were collected and edited by the Surrealist promoter Sașa Pană, who corresponded with him over several years.[131] The first such edition saw print in 1934, and featured the 1913–1915 poems Tzara had left in Vinea's care.[30] In 1928–1929, Tzara exchanged letters with his friend Jacques G. Costin, a Contimporanul affiliate who did not share all of Vinea's views on literature, who offered to organize his visit to Romania and asked him to translate his work into French.[132]

Alarmed by the establishment of Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime, which also signified the end of Berlin's avant-garde, he merged his activities as an art promoter with the cause of anti-fascism, and was close to the French Communist Party (PCF). In 1936, Richter recalled, he published a series of photographs secretly taken by Kurt Schwitters in Hanover, works which documented the destruction of Nazi propaganda by the locals, ration stamp with reduced quantities of food, and other hidden aspects of Hitler's rule.[133] After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, he briefly left France and joined the Republican forces.[84][134] Alongside Soviet reporter Ilya Ehrenburg, Tzara visited Madrid, which was besieged by the Nationalists (see Siege of Madrid).[135] Upon his return, he published the collection of poems Midis gagnés ("Conquered Southern Regions").[84] Some of them had previously been printed in the brochure Les poètes du monde défendent le peuple espagnol ("The Poets of the World Defend the Spanish People", 1937), which was edited by two prominent authors and activists, Nancy Cunard and the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda.[136] Tzara had also signed Cunard's June 1937 call to intervention against Francisco Franco.[137] Reportedly, he and Nancy Cunard were romantically involved.[138]

Although the poet was moving away from Surrealism,[67] his adherence to strict Marxism-Leninism was reportedly questioned by both the PCF and the Soviet Union.[139] Semiotician Philip Beitchman places their attitude in connection with Tzara's own vision of Utopia, which combined communist messages with Freudo-Marxist psychoanalysis and made use of particularly violent imagery.[140] Reportedly, Tzara refused to be enlisted in supporting the party line, maintaining his independence and refusing to take the forefront at public rallies.[141]

However, others note that the former Dadaist leader would often show himself a follower of political guidelines. As early as 1934, Tzara, together with Breton, Éluard and communist writer René Crevel, organized an informal trial of independent-minded Surrealist Salvador Dalí, who was at the time a confessed admirer of Hitler, and whose portrait of William Tell had alarmed them because it shared likeness with Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin.[142] Historian Irina Livezeanu notes that Tzara, who agreed with Stalinism and shunned Trotskyism, submitted to the PCF cultural demands during the writers' congress of 1935, even when his friend Crevel committed suicide to protest the adoption of socialist realism.[143] At a later stage, Livezeanu remarks, Tzara reinterpreted Dada and Surrealism as revolutionary currents, and presented them as such to the public.[144] This stance she contrasts with that of Breton, who was more reserved in his attitudes.[143]

During World War II, Tzara took refuge from the German occupation forces, moving to the southern areas, controlled by the Vichy regime.[4][84] On one occasion, the antisemitic and collaborationist publication Je Suis Partout made his whereabouts known to the Gestapo.[145]

He was in Marseille in late 1940-early 1941, joining the group of anti-fascist and Jewish refugees who, protected by American diplomat Varian Fry, were seeking to escape Nazi-occupied Europe. Among the people present there were the anti-totalitarian socialist Victor Serge, anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, playwright Arthur Adamov, philosopher and poet René Daumal, and several prominent Surrealists: Breton, Char, and Benjamin Péret, as well as artists Max Ernst, André Masson, Wifredo Lam, Jacques Hérold, Victor Brauner and Óscar Domínguez.[146] During the months spent together, and before some of them received permission to leave for America, they invented a new card game, on which traditional card imagery was replaced with Surrealist symbols.[146]

Some time after his stay in Marseille, Tzara joined the French Resistance, rallying with the Maquis. A contributor to magazines published by the Resistance, Tzara also took charge of the cultural broadcast for the Free French Forces clandestine radio station.[4][84] He lived in Aix-en-Provence, then in Souillac, and ultimately in Toulouse.[4] His son Cristophe was at the time a Resistant in northern France, having joined the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans.[145] In Axis-allied and antisemitic Romania (see Romania during World War II), the regime of Ion Antonescu ordered bookstores not to sell works by Tzara and 44 other Jewish-Romanian authors.[147] In 1942, with the generalization of antisemitic measures, Tzara was also stripped of his Romanian citizenship rights.[148]

In December 1944, five months after the Liberation of Paris, he was contributing to L'Éternelle Revue, a pro-communist newspaper edited by philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, through which Sartre was publicizing the heroic image of a France united in resistance, as opposed to the perception that it had passively accepted German control.[149] Other contributors included writers Aragon, Char, Éluard, Elsa Triolet, Eugène Guillevic, Raymond Queneau, Francis Ponge, Jacques Prévert and painter Pablo Picasso.[149]

Upon the end of the war and the restoration of French independence, Tzara was naturalized a French citizen.[84] During 1945, under the Provisional Government of the French Republic, he was a representative of the Sud-Ouest region to the National Assembly.[135] According to Livezeanu, he "helped reclaim the South from the cultural figures who had associated themselves to Vichy [France]."[143] In April 1946, his early poems, alongside similar pieces by Breton, Éluard, Aragon and Dalí, were the subject of a midnight broadcast on Parisian Radio.[150] In 1947, he became a full member of the PCF[67] (according to some sources, he had been one since 1934).[84]

Over the following decade, Tzara lent his support to political causes. Pursuing his interest in primitivism, he became a critic of the Fourth Republic's colonial policy, and joined his voice to those who supported decolonization.[141] Nevertheless, he was appointed cultural ambassador of the Republic by the Paul Ramadier cabinet.[151] He also participated in the PCF-organized Congress of Writers, but, unlike Éluard and Aragon, again avoided adapting his style to socialist realism.[145]

He returned to Romania on an official visit in late 1946-early 1947,[152][153] as part of a tour of the emerging Eastern Bloc during which he also stopped in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia.[153] The speeches he and Sașa Pană gave on the occasion, published by Orizont journal, were noted for condoning official positions of the PCF and the Romanian Communist Party, and are credited by Irina Livezeanu with causing a rift between Tzara and young Romanian avant-gardists such as Victor Brauner and Gherasim Luca (who rejected communism and were alarmed by the Iron Curtain having fallen over Europe).[154] In September of the same year, he was present at the conference of the pro-communist International Union of Students (where he was a guest of the French-based Union of Communist Students, and met with similar organizations from Romania and other countries).[155]

In 1949–1950, Tzara answered Aragon's call and become active in the international campaign to liberate Nazım Hikmet, a Turkish poet whose 1938 arrest for communist activities had created a cause célèbre for the pro-Soviet public opinion.[156][157] Tzara chaired the Committee for the Liberation of Nazım Hikmet, which issued petitions to national governments[157][158] and commissioned works in honor of Hikmet (including musical pieces by Louis Durey and Serge Nigg).[157] Hikmet was eventually released in July 1950, and publicly thanked Tzara during his subsequent visit to Paris.[159]

His works of the period include, among others: Le Signe de vie ("Sign of Life", 1946), Terre sur terre ("Earth on Earth", 1946), Sans coup férir ("Without a Need to Fight", 1949), De mémoire d'homme ("From a Man's Memory", 1950), Parler seul ("Speaking Alone", 1950), and La Face intérieure ("The Inner Face", 1953), followed in 1955 by À haute flamme ("Flame out Loud") and Le Temps naissant ("The Nascent Time"), and the 1956 Le Fruit permis ("The Permitted Fruit").[84][160] Tzara continued to be an active promoter of modernist culture. Around 1949, having read Irish author Samuel Beckett's manuscript of Waiting for Godot, Tzara facilitated the play's staging by approaching producer Roger Blin.[161] He also translated into French some poems by Hikmet[162] and the Hungarian author Attila József.[153] In 1949, he introduced Picasso to art dealer Heinz Berggruen (thus helping start their lifelong partnership),[163] and, in 1951, wrote the catalog for an exhibit of works by his friend Max Ernst; the text celebrated the artist's "free use of stimuli" and "his discovery of a new kind of humor."[164]

In October 1956, Tzara visited the People's Republic of Hungary, where the government of Imre Nagy was coming into conflict with the Soviet Union.[145][153] This followed an invitation on the part of Hungarian writer Gyula Illyés, who wanted his colleague to be present at ceremonies marking the rehabilitation of László Rajk (a local communist leader whose prosecution had been ordered by Joseph Stalin).[153] Tzara was receptive of the Hungarians' demand for liberalization,[145][153] contacted the anti-Stalinist and former Dadaist Lajos Kassák, and deemed the anti-Soviet movement "revolutionary".[153] However, unlike much of Hungarian public opinion, the poet did not recommend emancipation from Soviet control, and described the independence demanded by local writers as "an abstract notion".[153] The statement he issued, widely quoted in the Hungarian and international press, forced a reaction from the PCF: through Aragon's reply, the party deplored the fact that one of its members was being used in support of "anti-communist and anti-Soviet campaigns."[153]

His return to France coincided with the outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution, which ended with a Soviet military intervention. On 24 October, Tzara was ordered to a PCF meeting, where activist Laurent Casanova reportedly ordered him to keep silent, which Tzara did.[153] Tzara's apparent dissidence and the crisis he helped provoke within the Communist Party were celebrated by Breton, who had adopted a pro-Hungarian stance, and who defined his friend and rival as "the first spokesman of the Hungarian demand."[153]

He was thereafter mostly withdrawn from public life, dedicating himself to researching the work of 15th-century poet François Villon,[141] and, like his fellow Surrealist Michel Leiris, to promoting primitive and African art, which he had been collecting for years.[145] In early 1957, Tzara attended a Dada retrospective on the Rive Gauche, which ended in a riot caused by the rival avant-garde Mouvement Jariviste, an outcome which reportedly pleased him.[165] In August 1960, one year after the Fifth Republic had been established by President Charles de Gaulle, French forces were confronting the Algerian rebels (see Algerian War). Together with Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Duras, Jérôme Lindon, Alain Robbe-Grillet and other intellectuals, he addressed Premier Michel Debré a letter of protest, concerning France's refusal to grant Algeria its independence.[166] As a result, Minister of Culture André Malraux announced that his cabinet would not subsidize any films to which Tzara and the others might contribute, and the signatories could no longer appear on stations managed by the state-owned French Broadcasting Service.[166]

In 1961, as recognition for his work as a poet, Tzara was awarded the prestigious Taormina Prize.[84] One of his final public activities took place in 1962, when he attended the International Congress on African Culture, organized by English curator Frank McEwen and held at the National Gallery in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia.[167] He died one year later in his Paris home, and was buried at the Cimetière du Montparnasse.[4]

Much critical commentary about Tzara surrounds the measure to which the poet identified with the national cultures which he represented. Paul Cernat notes that the association between Samyro and the Jancos, who were Jews, and their ethnic Romanian colleagues, was one sign of a cultural dialogue, in which "the openness of Romanian environments toward artistic modernity" was stimulated by "young emancipated Jewish writers."[168] Salomon Schulman, a Swedish researcher of Yiddish literature, argues that the combined influence of Yiddish folklore and Hasidic philosophy shaped European modernism in general and Tzara's style in particular,[169] while American poet Andrei Codrescu speaks of Tzara as one in a Balkan line of "absurdist writing", which also includes the Romanians Urmuz, Eugène Ionesco and Emil Cioran.[170] According to literary historian George Călinescu, Samyro's early poems deal with "the voluptuousness over the strong scents of rural life, which is typical among Jews compressed into ghettos."[171]

Tzara himself used elements alluding to his homeland in his early Dadaist performances. His collaboration with Maja Kruscek at Zuntfhaus zür Waag featured samples of African literature, to which Tzara added Romanian-language fragments.[75] He is also known to have mixed elements of Romanian folklore, and to have sung the native suburban romanza La moară la Hârța ("At the Mill in Hârța") during at least one staging for Cabaret Voltaire.[172] Addressing the Romanian public in 1947, he claimed to have been captivated by "the sweet language of Moldavian peasants".[135]

Tzara nonetheless rebelled against his birthplace and upbringing. His earliest poems depict provincial Moldavia as a desolate and unsettling place. In Cernat's view, this imagery was in common use among Moldavian-born writers who also belonged to the avant-garde trend, notably Benjamin Fondane and George Bacovia.[173] Like in the cases of Eugène Ionesco and Fondane, Cernat proposes, Samyro sought self-exile to Western Europe as a "modern, voluntarist" means of breaking with "the peripheral condition",[174] which may also serve to explain the pun he selected for a pseudonym.[6] According to the same author, two important elements in this process were "a maternal attachment and a break with paternal authority", an "Oedipus complex" which he also argued was evident in the biographies of other Symbolist and avant-garde Romanian authors, from Urmuz to Mateiu Caragiale.[175] Unlike Vinea and the Contimporanul group, Cernat proposes, Tzara stood for radicalism and insurgency, which would also help explain their impossibility to communicate.[176] In particular, Cernat argues, the writer sought to emancipate himself from competing nationalisms, and addressed himself directly to the center of European culture, with Zürich serving as a stage on his way to Paris.[75] The 1916 Monsieur's Antipyrine's Manifesto featured a cosmopolitan appeal: "DADA remains within the framework of European weaknesses, it's still shit, but from now on we want to shit in different colors so as to adorn the zoo of art with all the flags of all the consulates."[75]

With time, Tristan Tzara came to be regarded by his Dada associates as an exotic character, whose attitudes were intrinsically linked with Eastern Europe. Early on, Ball referred to him and the Janco brothers as "Orientals".[36] Hans Richter believed him to be a fiery and impulsive figure, having little in common with his German collaborators.[177] According to Cernat, Richter's perspective seems to indicate a vision of Tzara having a "Latin" temperament.[36] This type of perception also had negative implications for Tzara, particularly after the 1922 split within Dada. In the 1940s, Richard Huelsenbeck alleged that his former colleague had always been separated from other Dadaists by his failure to appreciate the legacy of "German humanism", and that, compared to his German colleagues, he was "a barbarian".[107] In his polemic with Tzara, Breton also repeatedly placed stress on his rival's foreign origin.[178]

At home, Tzara was occasionally targeted for his Jewishness, culminating in the ban enforced by the Ion Antonescu regime. In 1931, Const. I. Emilian, the first Romanian to write an academic study on the avant-garde, attacked him from a conservative and antisemitic position. He depicted Dadaists as "Judaeo-Bolsheviks" who corrupted Romanian culture, and included Tzara among the main proponents of "literary anarchism".[179] Alleging that Tzara's only merit was to establish a literary fashion, while recognizing his "formal virtuosity and artistic intelligence", he claimed to prefer Tzara in his Simbolul stage.[180] This perspective was deplored early on by the modernist critic Perpessicius.[181] Nine years after Emilian's polemic text, fascist poet and journalist Radu Gyr published an article in Convorbiri Literare, in which he attacked Tzara as a representative of the "Judaic spirit", of the "foreign plague" and of "materialist-historical dialectics".[182]

Tzara's earliest Symbolist poems, published in Simbolul during 1912, were later rejected by their author, who asked Sașa Pană not to include them in editions of his works.[15] The influence of French Symbolists on the young Samyro was particularly important, and surfaced in both his lyric and prose poems.[25][84][183] Attached to Symbolist musicality at that stage, he was indebted to his Simbolul colleague Ion Minulescu[184] and the Belgian Maurice Maeterlinck.[15] Philip Beitchman argues that "Tristan Tzara is one of the writers of the twentieth century who was most profoundly influenced by symbolism—and utilized many of its methods and ideas in the pursuit of his own artistic and social ends."[185] However, Cernat believes, the young poet was by then already breaking with the syntax of conventional poetry, and that, in subsequent experimental pieces, he progressively stripped his style of its Symbolist elements.[186]

During the 1910s, Samyro experimented with Symbolist imagery, in particular with the "hanged man" motif, which served as the basis for his poem Se spânzură un om ("A Man Hangs Himself"), and which built on the legacy of similar pieces authored by Christian Morgenstern and Jules Laforgue.[187] Se spânzură un om was also in many ways similar to ones authored by his collaborators Adrian Maniu (Balada spânzuratului, "The Hanged Man's Ballad") and Vinea (Visul spânzuratului, "The Hanged Man's Dream"): all three poets, who were all in the process of discarding Symbolism, interpreted the theme from a tragicomic and iconoclastic perspective.[187] These pieces also include Vacanță în provincie ("Provincial Holiday") and the anti-war fragment Furtuna și cântecul dezertorului ("The Storm and the Deserter's Song"), which Vinea published in his Chemarea.[188] The series is seen by Cernat as "the general rehearsal for the Dada adventure."[189] The complete text of Furtuna și cântecul dezertorului was published at a later stage, after the missing text was discovered by Pană.[190] At the time, he became interested in the free verse work of the American Walt Whitman, and his translation of Whitman's epic poem Song of Myself, probably completed before World War I, was published by Alfred Hefter-Hidalgo in his magazine Versuri și Proză (1915).[191]

Beitchman notes that, throughout his life, Tzara used Symbolist elements against the doctrines of Symbolism. Thus, he argues, the poet did not cultivate a memory of historical events, "since it deludes man into thinking that there was something when there was nothing."[192] Cernat notes: "That which essentially unifies, during [the 1910s], the poetic output of Adrian Maniu, Ion Vinea and Tristan Tzara is an acute awareness of literary conventions, a satiety [...] in respect to calophile literature, which they perceived as exhausted."[193] In Beitchman's view, the revolt against cultivated beauty was a constant in Tzara's years of maturity, and his visions of social change continued to be inspired by Arthur Rimbaud and the Comte de Lautréamont.[194] According to Beitchman, Tzara uses the Symbolist message, "the birthright [of humans] has been sold for a mess of porridge", taking it "into the streets, cabarets and trains where he denounces the deal and asks for his birthright back."[195]

The transition to a more radical form of poetry seems to have taken place in 1913–1915, during the periods when Tzara and Vinea were vacationing together. The pieces share a number of characteristics and subjects, and the two poets even use them to allude to one another (or, in one case, to Tzara's sister).[196]

In addition to the lyrics were they both speak of provincial holidays and love affairs with local girls, both friends intended to reinterpret William Shakespeare's Hamlet from a modernist perspective, and wrote incomplete texts with this as their subject.[197] However, Paul Cernat notes, the texts also evidence a difference in approach, with Vinea's work being "meditative and melancholic", while Tzara's is "hedonistic".[198] Tzara often appealed to revolutionary and ironic images, portraying provincial and middle class environments as places of artificiality and decay, demystifying pastoral themes and evidencing a will to break free.[199] His literature took a more radical perspective on life, and featured lyrics with subversive intent:

să ne coborâm în râpa, |

let's descend into the precipice |

In his Înserează (roughly, "Night Falling"), probably authored in Mangalia, Tzara writes:

[...] deschide-te fereastră, prin urmare |

[...] open yourself therefore, window |

Vinea's similar poem, written in Tuzla and named after that village, reads:

seara bate semne pe far |

the evening stamps signs on the lighthouse |

Cernat notes that Nocturnă ("Nocturne") and Înserează were the pieces originally performed at Cabaret Voltaire, identified by Hugo Ball as "Rumanian poetry", and that they were recited in Tzara's own spontaneous French translation.[201] Although they are noted for their radical break with the traditional form of Romanian verse,[202] Ball's diary entry of 5 February 1916, indicates that Tzara's works were still "conservative in style".[203] In Călinescu's view, they announce Dadaism, given that "bypassing the relations which lead to a realistic vision, the poet associates unimaginably dissipated images that will surprise consciousness."[171] In 1922, Tzara himself wrote: "As early as 1914, I tried to strip the words of their proper meaning and use them in such a way as to give the verse a completely new, general, meaning [...]."[202]

Alongside pieces depicting a Jewish cemetery in which graves "crawl like worms" on the edge of a town, chestnut trees "heavy-laden like people returning from hospitals", or wind wailing "with all the hopelessness of an orphanage",[171] Samyro's poetry includes Verișoară, fată de pension, which, Cernat argues, displays "playful detachment [for] the musicality of internal rhymes".[15] It opens with the lyrics:

Verișoară, fată de pension, îmbrăcată în negru, guler alb, |

Little cousin, boarding school girl, dressed in black, white collar, |

The Gârceni pieces were treasured by the moderate wing of the Romanian avant-garde movement. In contrast to his previous rejection of Dada, Contimporanul collaborator Benjamin Fondane used them as an example of "pure poetry", and compared them to the elaborate writings of French poet Paul Valéry, thus recuperating them in line with the magazine's ideology.[204]

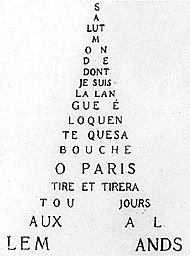

Tzara the Dadaist was inspired by the contributions of his experimental modernist predecessors. Among them were the literary promoters of Cubism: in addition to Henri Barzun and Fernand Divoire, Tzara cherished the works of Guillaume Apollinaire.[145][205] Despite Dada's condemnation of Futurism, various authors note the influence Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and his circle exercised on Tzara's group.[206] In 1917, he was in correspondence with both Apollinaire[207] and Marinetti.[208] Traditionally, Tzara is also seen as indebted to the early avant-garde and black comedy writings of Romania's Urmuz.[202][209]

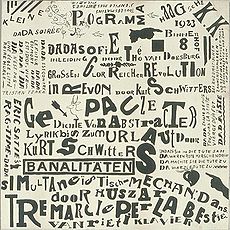

For a large part, Dada focused on performances and satire, with shows that often had Tzara, Marcel Janco and Huelsenbeck for their main protagonists. Often dressed up as Tyrolian peasants or wearing dark robes, they improvised poetry sessions at the Cabaret Voltaire, reciting the works of others or their spontaneous creations, which were or pretended to be in Esperanto or Māori language.[210] Bernard Gendron describes these soirées as marked by "heterogeneity and eclecticism",[211] and Richter notes that the songs, often punctuated by loud shrieks or other unsettling sounds, built on the legacy of noise music and Futurist compositions.[212]

With time, Tristan Tzara merged his performances and his literature, taking part in developing Dada's "simultaneist poetry", which was meant to be read out loud and involved a collaborative effort, being, according to Hans Arp, the first instance of Surrealist automatism.[203] Ball stated that the subject of such pieces was "the value of the human voice."[213] Together with Arp, Tzara and Walter Serner produced the German-language Die Hyperbel vom Krokodilcoiffeur und dem Spazierstock ("The Hyperbole of the Crocodile's Hairdresser and the Walking-Stick"), in which, Arp stated, "the poet crows, curses, sighs, stutters, yodels, as he pleases. His poems are like Nature [where] a tiny particle is as beautiful and important as a star."[214] Another noted simultaneist poem was L'Amiral cherche une maison à louer ("The Admiral Is Looking for a House to Rent"), co-authored by Tzara, Marcel Janco and Huelsenbach.[171]

Art historian Roger Cardinal describes Tristan Tzara's Dada poetry as marked by "extreme semantic and syntactic incoherence".[67] Tzara, who recommended destroying just as it is created,[215] had devised a personal system for writing poetry, which implied a seemingly chaotic reassembling of words that had been randomly cut out of newspapers.[109][216][217]

The Romanian writer also spent the Dada period issuing a long series of manifestos, which were often authored as prose poetry,[84] and, according to Cardinal, were characterized by "rumbustious tomfoolery and astringent wit", which reflected "the language of a sophisticated savage".[67] Huelsenbeck credited Tzara with having discovered in them the format for "compress[ing] what we think and feel",[218] and, according to Hans Richter, the genre "suited Tzara perfectly."[49] Despite its production of seemingly theoretical works, Richter indicates, Dada lacked any form of program, and Tzara tried to perpetuate this state of affairs.[219] His Dada manifesto of 1918 stated: "Dada means nothing", adding "Thought is produced in the mouth."[220] Tzara indicated: "I am against systems; the most acceptable system is on principle to have none."[4] In addition, Tzara, who once stated that "logic is always false",[221] probably approved of Serner's vision of a "final dissolution".[222] According to Philip Beitchman, a core concept in Tzara's thought was that "as long as we do things the way we think we once did them we will be unable to achieve any kind of livable society."[192]

Despite adopting such anti-artistic principles, Richter argues, Tzara, like many of his fellow Dadaists, did not initially discard the mission of "furthening the cause of art."[223] He saw this evident in La Revue Dada 2, a poem "as exquisite as freshly-picked flowers", which included the lyrics:

Cinq négresses dans une auto |

Five Negro women in a car |

La Revue Dada 2, which also includes the onomatopoeic line tralalalalalalalalalalala, is one example where Tzara applies his principles of chance to sounds themselves.[223] This sort of arrangement, treasured by many Dadaists, was probably connected with Apollinaire's calligrams, and with his announcement that "Man is in search of a new language."[224] Călinescu proposed that Tzara willingly limited the impact of chance: taking as his example a short parody piece which depicts the love affair between cyclist and a Dadaist, which ends with their decapitation by a jealous husband, the critic notes that Tzara transparently intended to "shock the bourgeois".[171] Late in his career, Huelsenbeck alleged that Tzara never actually applied the experimental methods he had devised.[41]

The Dada series makes ample use of contrast, ellipses, ridiculous imagery and nonsensical verdicts.[84] Tzara was aware that the public could find it difficult to follow his intentions, and, in a piece titled Le géant blanc lépreux du paysage ("The White Leprous Giant in the Landscape") even alluded to the "skinny, idiotic, dirty" reader who "does not understand my poetry."[84] He called some of his own poems lampisteries, from a French word designating storage areas for light fixtures.[225] The Lettrist poet Isidore Isou included such pieces in a succession of experiments inaugurated by Charles Baudelaire with the "destruction of the anecdote for the form of the poem", a process which, with Tzara, became "destruction of the word for nothing".[226] According to American literary historian Mary Ann Caws, Tzara's poems may be seen as having an "internal order", and read as "a simple spectacle, as creation complete in itself and completely obvious."[84]

Tristan Tzara's first play, The Gas Heart, dates from the final period of Paris Dada. Created with what Enoch Brater calls a "peculiar verbal strategy", it is a dialogue between characters called Ear, Mouth, Eye, Nose, Neck, and Eyebrow.[227] They seem unwilling to actually communicate to each other and their reliance on proverbs and idiotisms willingly creates confusion between metaphorical and literal speech.[227] The play ends with a dance performance that recalls similar devices used by the proto-Dadaist Alfred Jarry. The text culminates in a series of doodles and illegible words.[228] Brater describes The Gas Heart as a "parod[y] of theatrical conventions".[228]

In his 1924 play Handkerchief of Clouds, Tzara explores the relation between perception, the subconscious and memory. Largely through exchanges between commentators who act as third parties, the text presents the tribulations of a love triangle (a poet, a bored woman, and her banker husband, whose character traits borrow the clichés of conventional drama), and in part reproduces settings and lines from Hamlet.[229] Tzara mocks classical theater, which demands from characters to be inspiring, believable, and to function as a whole: Handkerchief of Clouds requires actors in the role of commentators to address each other by their real names,[230] and their lines include dismissive comments on the play itself, while the protagonist, who in the end dies, is not assigned any name.[231] Writing for Integral, Tzara defined his play as a note on "the relativity of things, sentiments and events."[232] Among the conventions ridiculed by the dramatist, Philip Beitchman notes, is that of a "privileged position for art": in what Beitchman sees as a comment on Marxism, poet and banker are interchangeable capitalists who invest in different fields.[233] Writing in 1925, Fondane rendered a pronouncement by Jean Cocteau, who, while commenting that Tzara was one of his "most beloved" writers and a "great poet", argued: "Handkerchief of Clouds was poetry, and great poetry for that matter—but not theater."[234] The work was nonetheless praised by Ion Călugăru at Integral, who saw in it one example that modernist performance could rely not just on props, but also on a solid text.[126]

After 1929, with the adoption of Surrealism, Tzara's literary works discard much of their satirical purpose, and begin to explore universal themes relating to the human condition.[84] According to Cardinal, the period also signified the definitive move from "a studied inconsequentiality" and "unreadable gibberish" to "a seductive and fertile surrealist idiom."[67] The critic also remarks: "Tzara arrived at a mature style of transparent simplicity, in which disparate entities could be held together in a unifying vision."[67] In a 1930 essay, Fondane had given a similar verdict: arguing that Tzara had infused his work with "suffering", had discovered humanity, and had become a "clairvoyant" among poets.[235]

This period in Tzara's creative activity centers on The Approximate Man, an epic poem which is reportedly recognized as his most accomplished contribution to French literature.[67][84] While maintaining some of Tzara's preoccupation with language experimentation, it is mainly a study in social alienation and the search for an escape.[84][236] Cardinal calls the piece "an extended meditation on mental and elemental impulses [...] with images of stunning beauty",[67] while Breitchman, who notes Tzara's rebellion against the "excess baggage of [man's] past and the notions [...] with which he has hitherto tried to control his life", remarks his portrayal of poets as voices who can prevent human beings from destroying themselves with their own intellects.[237] The goal is a new man who lets intuition and spontaneity guide him through life, and who rejects measure.[238] One of the appeals in the text reads:

je parle de qui parle qui parle je suis seul |

I speak of the one who speaks who speaks I am alone |

The next stage in Tzara's career saw a merger of his literary and political views. His poems of the period blend a humanist vision with communist theses.[84][139] The 1935 Grains et issues, described by Beitchman as "fascinating",[239] was a prose poem of social criticism connected with The Approximate Man, expanding on the vision of a possible society, in which haste has been abandoned in favor of oblivion. The world imagined by Tzara abandons symbols of the past, from literature to public transportation and currency, while, like psychologists Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Reich, the poet depicts violence as a natural means of human expression.[240] People of the future live in a state which combines waking life and the realm of dreams, and life itself turns into revery.[241] Grains et issues was accompanied by Personage d'insomnie ("Personage of Insomnia"), which went unpublished.[242]

Cardinal notes: "In retrospect, harmony and contact had been Tzara's goals all along."[67] The post-World War II volumes in the series focus on political subjects related to the conflict.[84] In his last writings, Tzara toned down experimentation, exercising more control over the lyrical aspects.[84] He was by then undertaking a hermeutic research into the work of Goliards and François Villon, whom he deeply admired.[141][145]

Beside the many authors who were attracted into Dada through his promotional activities, Tzara was able to influence successive generations of writers. This was the case in his homeland during 1928, when the first avant-garde manifesto issued by unu magazine, written by Sașa Pană and Moldov, cited as its mentors Tzara, writers Breton, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Vinea, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and Tudor Arghezi, as well as artists Constantin Brâncuși and Theo van Doesburg.[243] One of the Romanian writers to claim inspiration from Tzara was Jacques G. Costin, who nevertheless offered an equally good reception to both Dadaism and Futurism,[244] while Ilarie Voronca's Zodiac cycle, first published in France, is traditionally seen as indebted to The Approximate Man.[245] The Kabbalist and Surrealist author Marcel Avramescu, who wrote during the 1930s, also appears to have been directly inspired by Tzara's views on art.[221] Other authors from that generation to have been inspired by Tzara were Polish Futurist writer Bruno Jasieński,[246] Japanese poet and Zen thinker Takahashi Shinkichi,[247] and Chilean poet and Dadaist sympathizer Vicente Huidobro, who cited him as a precursor for his own Creacionismo.[248]

An immediate precursor of Absurdism, he was acknowledged as a mentor by Eugène Ionesco, who developed on his principles for his early essays of literary and social criticism, as well as in tragic farces such as The Bald Soprano.[249] Tzara's poetry influenced Samuel Beckett (who translated some of it into English);[161] the Irish author's 1972 play Not I shares some elements with The Gas Heart.[250] In the United States, the Romanian author is cited as an influence on Beat Generation members. Beat writer Allen Ginsberg, who made his acquaintance in Paris, cites him among the Europeans who influenced him and William S. Burroughs.[251] The latter also mentioned Tzara's use of chance in writing poetry as an early example of what became the cut-up technique, adopted by Brion Gysin and Burroughs himself.[217] Gysin, who conversed with Tzara in the late 1950s, records the latter's indignation that Beat poets were "going back over the ground we [Dadaists] covered in 1920", and accuses Tzara of having consumed his creative energies into becoming a "Communist Party bureaucrat".[109]

Among the late 20th-century writers who acknowledged Tzara as an inspiration are Jerome Rothenberg,[252] Isidore Isou and Andrei Codrescu. The former Situationist Isou, whose experiments with sounds and poetry come in succession to Apollinaire and Dada,[224] declared his Lettrism to be the last connection in the Charles Baudelaire-Tzara cycle, with the goal of arranging "a nothing [...] for the creation of the anecdote."[226] For a short period, Codrescu even adopted the pen name Tristan Tzara.[7][253] He recalled the impact of having discovered Tzara's work in his youth, and credited him with being "the most important French poet after Rimbaud."[7]

In retrospect, various authors describe Tzara's Dadaist shows and street performances as "happenings", with a word employed by post-Dadaists and Situationists, which was coined in the 1950s.[254] Some also credit Tzara with having provided an ideological source for the development of rock music, including punk rock, punk subculture and post-punk.[7][255] Tristan Tzara has inspired the songwriting technique of Radiohead,[256] and is one of the avant-garde authors whose voices were mixed by DJ Spooky on his trip hop album Rhythm Science.[257] Romanian contemporary classical musician Cornel Țăranu set to music five of Tzara's poems, all of which date from the post-Dada period.[258] Țăranu, Anatol Vieru and ten other composers contributed to the album La Clé de l'horizon, inspired by Tzara's work.[259]

In France, Tzara's work was collected as Oeuvres complètes ("Complete Works"), of which the first volume saw print in 1975,[67] and an international poetry award is named after him (Prix International de Poésie Tristan Tzara). An international periodical titled Caietele Tristan Tzara, edited by the Tristan Tzara Cultural-Literary Foundation, has been published in Moinești since 1998.[259][260]

According to Paul Cernat, Aliluia, one of the few avant-garde texts authored by Ion Vinea features a "transparent allusion" to Tristan Tzara.[261] Vinea's fragment speaks of "the Wandering Jew", a character whom people notice because he sings La moară la Hârța, "a suspicious song from Greater Romania."[262] The poet is a character in Indian novelist Mulk Raj Anand's Thieves of Fire, part four of his The Bubble (1984),[263] as well as in The Prince of West End Avenue, a 1994 book by the American Alan Isler.[264] Rothenberg dedicated several of his poems to Tzara,[252] as did the Neo-Dadaist Valery Oișteanu.[265] Tzara's legacy in literature also covers specific episodes of his biography, beginning with Gertrude Stein's controversial memoir. One of his performances is enthusiastically recorded by Malcolm Cowley in his autobiographical book of 1934, Exile's Return,[266] and he is also mentioned in Harold Loeb's memoir The Way It Was.[267] Among his biographers is the French author François Buot, who records some of the lesser-known aspects of Tzara's life.[141]

At some point between 1915 and 1917, Tzara is believed to have played chess in a coffeehouse that was also frequented by Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin.[268] While Richter himself recorded the incidental proximity of Lenin's lodging to the Dadaist milieu,[203] no record exists of an actual conversation between the two figures.[269][270] Andrei Codrescu believes that Lenin and Tzara did play against each other, noting that an image of their encounter would be "the proper icon of the beginning of [modern] times."[269] This meeting is mentioned as a fact in Harlequin at the Chessboard, a poem by Tzara's acquaintance Kurt Schwitters.[271] German playwright and novelist Peter Weiss, who has introduced Tzara as a character in his 1969 play about Leon Trotsky (Trotzki im Exil), recreated the scene in his 1975–1981 cycle The Aesthetics of Resistance.[272] The imagined episode also inspired much of Tom Stoppard's 1974 play Travesties, which also depicts conversations between Tzara, Lenin, and the Irish modernist author James Joyce (who is also known to have resided in Zürich after 1915).[270][273][274] His role was notably played by David Westhead in the 1993 British production,[273] and by Tom Hewitt in the 2005 American version.[274]

Alongside his collaborations with Dada artists on various pieces, Tzara himself was a subject for visual artists. Max Ernst depicts him as the only mobile character in the Dadaists' group portrait Au Rendez-vous des Amis ("A Friends' Reunion", 1922),[141] while, in one of Man Ray's photographs, he is shown kneeling to kiss the hand of an androgynous Nancy Cunard.[275] Years before their split, Francis Picabia used Tzara's calligraphed name in Moléculaire ("Molecular"), a composition printed on the cover of 391.[276] The same artist also completed his schematic portrait, which showed a series of circles connected by two perpendicular arrows.[277] In 1949, Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti made Tzara the subject of one of his first experiments with lithography.[278] Portraits of Tzara were also made by Greta Knutson,[279] Robert Delaunay,[280] and the Cubist painters M. H. Maxy[281] and Lajos Tihanyi. As an homage to Tzara the performer, art rocker David Bowie adopted his accessories and mannerisms during a number of public appearances.[282] In 1996, he was depicted on a series of Romanian stamps, and, the same year, a concrete and steel monument dedicated to the writer was erected in Moinești.[259]

Several of Tzara's Dadaist editions had illustrations by Picabia, Janco and Hans Arp.[160] In its 1925 edition, Handkerchief of Clouds featured etchings by Juan Gris, while his late writings Parler seul, Le Signe de vie, De mémoire d'homme, Le Temps naissant, and Le Fruit permis were illustrated with works by, respectively, Joan Miró,[283] Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Nejad Devrim[160] and Sonia Delaunay.[284] Tzara was the subject of a 1949 eponymous documentary film directed by Danish filmmaker Jørgen Roos, and footage of him featured prominently in the 1953 production Les statues meurent aussi ("Statues Also Die"), jointly directed by Chris Marker and Alain Resnais.[127]