| Part of a series on |

| Stalinism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism–Leninism |

|---|

|

Stalinism (Russian: Сталинизм, Stalinizm) is the totalitarian[1][2][3] means of governing and Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from 1927 to 1953 by dictator Joseph Stalin. Stalin had previously made a career as a gangster and robber,[4] working to fund revolutionary activities, before eventually becoming General Secretary of the Soviet Union. Stalinism included the creation of a one man[5][6] totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory of socialism in one country (until 1939), forced collectivization of agriculture, intensification of class conflict, a cult of personality,[7][8] and subordination of the interests of foreign communist parties to those of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which Stalinism deemed the leading vanguard party of communist revolution at the time.[9] After Stalin's death and the Khrushchev Thaw, a period of de-Stalinization began in the 1950s and 1960s, which caused the influence of Stalin's ideology to begin to wane in the USSR.

Stalin's regime forcibly purged society of what it saw as threats to itself and its brand of communism (so-called "enemies of the people"), which included political dissidents, non-Soviet nationalists, the bourgeoisie, better-off peasants ("kulaks"),[10] and those of the working class who demonstrated "counter-revolutionary" sympathies.[11] This resulted in mass repression of such people and their families, including mass arrests, show trials, executions, and imprisonment in forced labor camps known as gulags.[12] The most notorious examples were the Great Purge and the Dekulakization campaign. Stalinism was also marked by militant atheism, mass anti-religious persecution,[13][14] and ethnic cleansing through forced deportations.[15] Some historians, such as Robert Service, have blamed Stalinist policies, particularly collectivization, for causing famines such as the Holodomor.[13] Other historians and scholars disagree on Stalinism's role.[16]

Officially designed to accelerate development toward communism, the need for industrialization in the Soviet Union was emphasized because the Soviet Union had previously fallen behind economically compared to Western countries and also because socialist society needed industry to face the challenges posed by internal and external enemies of communism.[17] Rapid industrialization was accompanied by mass collectivization of agriculture and rapid urbanization, which converted many small villages into industrial cities.[18] To accelerate industrialization's development, Stalin imported materials, ideas, expertise, and workers from western Europe and the United States,[19] pragmatically setting up joint-venture contracts with major American private enterprises such as the Ford Motor Company, which, under state supervision, assisted in developing the basis of the industry of the Soviet economy from the late 1920s to the 1930s. After the American private enterprises had completed their tasks, Soviet state enterprises took over.

History

Stalinism is used to describe the period during which Joseph Stalin was the leader of the Soviet Union while serving as General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1922 to his death on 5 March 1953.[20] It was a development of Leninism,[21] and while Stalin avoided using the term "Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism", he allowed others to do so.[22] Following Lenin's death, Stalin contributed to the theoretical debates within the Communist Party, namely by developing the idea of "Socialism in One Country". This concept was intricately linked to factional struggles within the party, particularly against Trotsky.[23] He first developed the idea in December 1924 and elaborated upon in his writings of 1925–26.[24]

Stalin's doctrine held that socialism could be completed in Russia but that its final victory could not be guaranteed because of the threat from capitalist intervention. For this reason, he retained the Leninist view that world revolution was still a necessity to ensure the ultimate victory of socialism.[24] Although retaining the Marxist belief that the state would wither away as socialism transformed into pure communism, he believed that the Soviet state would remain until the final defeat of international capitalism.[25] This concept synthesised Marxist and Leninist ideas with nationalist ideals,[26] and served to discredit Trotsky—who promoted the idea of "permanent revolution"—by presenting the latter as a defeatist with little faith in Russian workers' abilities to construct socialism.[27]

Etymology

The term Stalinism came into prominence during the mid-1930s when Lazar Kaganovich, a Soviet politician and associate of Stalin, reportedly declared: "Let's replace Long Live Leninism with Long Live Stalinism!"[28] Stalin dismissed this as excessive and contributing to a cult of personality he thought might later be used against him by the same people who praised him excessively, one of those being Khrushchev—a prominent user of the term during Stalin's life who was later responsible for de-Stalinization and the beginning of the Revisionist period.[28]

Stalinist policies

Some historians view Stalinism as a reflection of the ideologies of Leninism and Marxism, but some argue that it is separate from the socialist ideals it stemmed from. After a political struggle that culminated in the defeat of the Bukharinists (the "Party's Right Tendency"), Stalinism was free to shape policy without opposition, ushering in an era of harsh totalitarianism that worked toward rapid industrialization regardless of the human cost.[31]

From 1917 to 1924, though often appearing united, Stalin, Vladimir Lenin, and Leon Trotsky had discernible ideological differences. In his dispute with Trotsky, Stalin de-emphasized the role of workers in advanced capitalist countries (e.g., he considered the U.S. working class "bourgeoisified" labor aristocracy).

All other October Revolution 1917 Bolshevik leaders regarded their revolution more or less as just the beginning, with Russia as the springboard on the road toward worldwide revolution. Stalin introduced the idea of socialism in one country by the autumn of 1924, a theory standing in sharp contrast to Trotsky's permanent revolution and all earlier socialistic theses. The revolution did not spread outside Russia as Lenin had assumed it soon would. The revolution had not succeeded even within other former territories of the Russian Empire―such as Poland, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. On the contrary, these countries had returned to capitalist bourgeois rule.[32]

He is an unprincipled intriguer, who subordinates everything to the preservation of his own power. He changes his theory according to whom he needs to get rid of.

Bukharin on Stalin's theoretical position, 1928.[33]

Despite this, by the autumn of 1924, Stalin's notion of socialism in Soviet Russia was initially considered next to blasphemy by other Politburo members, including Zinoviev and Kamenev to the intellectual left; Rykov, Bukharin, and Tomsky to the pragmatic right; and the powerful Trotsky, who belonged to no side but his own. None would even consider Stalin's concept a potential addition to communist ideology. Stalin's socialism in one country doctrine could not be imposed until he had come close to being the Soviet Union's autocratic ruler around 1929. Bukharin and the Right Opposition expressed their support for imposing Stalin's ideas, as Trotsky had been exiled, and Zinoviev and Kamenev had been expelled from the party.[34] In a 1936 interview with journalist Roy W. Howard, Stalin articulated his rejection of world revolution and said, "We never had such plans and intentions" and "The export of revolution is nonsense".[35][36][37]

Proletarian state

Traditional communist thought holds that the state will gradually "wither away" as the implementation of socialism reduces class distinction. But Stalin argued that the proletarian state (as opposed to the bourgeois state) must become stronger before it can wither away. In Stalin's view, counter-revolutionary elements will attempt to derail the transition to full communism, and the state must be powerful enough to defeat them. For this reason, communist regimes influenced by Stalin are totalitarian.[38] Other leftists, such as anarcho-communists, have criticized the party-state of the Stalin-era Soviet Union, accusing it of being bureaucratic and calling it a reformist social democracy rather than a form of revolutionary communism.[39]

Sheng Shicai, a Chinese warlord with Communist leanings, invited Soviet intervention and allowed Stalinist rule to extend to Xinjiang province in the 1930s. In 1937, Sheng conducted a purge similar to the Great Purge, imprisoning, torturing, and killing about 100,000 people, many of them Uyghurs.[40][41]

Ideological repression and censorship

Cybernetics: a reactionary pseudoscience that appeared in the U.S.A. after World War II and also spread through other capitalist countries. Cybernetics clearly reflects one of the basic features of the bourgeois worldview—its inhumanity, striving to transform workers into an extension of the machine, into a tool of production, and an instrument of war. At the same time, for cybernetics an imperialistic utopia is characteristic—replacing living, thinking man, fighting for his interests, by a machine, both in industry and in war. The instigators of a new world war use cybernetics in their dirty, practical affairs.

"Cybernetics" in the Short Philosophical Dictionary, 1954[42]

Under Stalin, repression was extended to academic scholarship, the natural sciences,[43] and literary fields.[44] In particular, Einstein's theory of relativity was subject to public denunciation, many of his ideas were rejected on ideological grounds[45] and condemned as "bourgeois idealism" in the Stalin era.[46]

A policy of ideological repression impacted various disciplinary fields such as genetics,[47] cybernetics,[48] biology,[49] linguistics,[50][51] physics,[52] sociology,[53] psychology,[54] pedology,[55] mathematical logic,[56] economics[57] and statistics.[58]

Pseudoscientific theories of Trofim Lysenko were favoured over other scientific disciplines during the Stalin era.[48] Soviet scientists were forced to denounce any work that contradicted Lysenko.[59] Over 3,000 biologists were imprisoned, fired,[60] or executed for attempting to oppose Lysenkoism and genetic research was effectively destroyed until the death of Stalin in 1953.[61][62] Due to the ideological influence of Lysenkoism, crop yields in the USSR declined.[63][64][61]

Orthodoxy was enforced in the cultural sphere. Prior to Stalin's rule, literary, religious and national representatives had some level of autonomy in the 1920s but these groups were later rigorously repressed during the Stalinist era.[65] Socialist realism was imposed in artistic production and other creative industries such as music, film along with sports were subject to extreme levels of political control.[66]

Historical falsification of political events such as the October Revolution and the Brest-Litovsk Treaty became a distinctive element of Stalin's regime. A notable example is the 1938 publication, History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks),[67] in which the history of the governing party was significantly altered and revised including the importance of the leading figures during the Bolshevik revolution. Retrospectively, Lenin's primary associates such as Zinoviev, Trotsky, Radek and Bukharin were presented as "vacillating", "opportunists" and "foreign spies" whereas Stalin was depicted as the chief discipline during the revolution. However, in reality, Stalin was considered a relatively unknown figure with secondary importance at the time of the event.[68]

In his book, The Stalin School of Falsification, Leon Trotsky argued that the Stalinist faction routinely distorted political events, forged a theoretical basis for irreconcilable concepts such as the notion of "Socialism in One Country" and misrepresented the views of opponents through an array of employed historians alongside economists to justify policy manoeuvering and safeguarding its own set of material interests.[69] He cited a range of historical documents such as private letters, telegrams, party speeches, meeting minutes, and suppressed texts such as Lenin's Testament.[70] British historian Orlando Figes argued that "The urge to silence Trotsky, and all criticism of the Politburo, was in itself a crucial factor in Stalin's rise to power".[71]

Cinematic productions served to foster the cult of personality around Stalin with adherents to the party line receiving Stalin prizes.[72] Although, film directors and their assistants were still liable to mass arrests during the Great Terror.[73] Censorship of films contributed to a mythologizing of history as seen with the films First Cavalry Army (1941) and Defence of Tsaritsyn (1942) in which Stalin was glorified as a central figure to the October Revolution. Conversely, the roles of other Soviet figures such as Lenin and Trotsky were diminished or misrepresented.[74]

Cult of personality

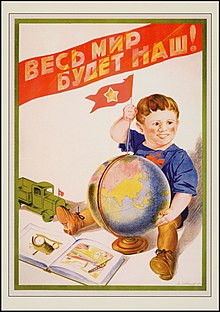

In the aftermath of the succession struggle, in which Stalin had defeated both Left and Right Opposition, a cult of Stalin had materialised.[75] From 1929 until 1953, there was a proliferation of architecture, statues, posters, banners and iconography featuring Stalin in which he was increasingly identified with the state and seen as an emblem of Marxism.[76] In July 1930, a state decree instructed 200 artists to prepare propaganda posters for the Five Year Plans and collectivsation measures.[77] Historian Anita Pisch drew specific focus to the various manifestations of the personality cult in which Stalin was associated with the "Father", "Saviour" and "Warrior" cultural archetypes with the latter imagery having gained ascendency during the Great Patrotic War and Cold War.[76]

Some scholars have argued that Stalin took an active involvement with the construction of the cult of personality[78] with writers such as Isaac Deutscher and Erik van Ree noting that Stalin had absorbed elements from the cult of Tsars, Orthodox Christianity and highlighting specific acts such as Lenin's embalming.[79] Yet, other scholars have drawn on primary accounts from Stalin's associates such as Molotov which suggested he took a more critical and ambivalent attitude towards his cult of personality.[80]

The cult of personality served to legitimate Stalin's authority, establish continuity with Lenin as his "discipline, student and mentee" in the view of his wider followers.[76][81] His successor, Nikita Khrushchev, would later denounce the cult of personality around Stalin as contradictory to Leninist principles and party discourse.[82]

Class-based violence

Stalin blamed the kulaks for inciting reactionary violence against the people during the implementation of agricultural collectivization.[83] In response, the state, under Stalin's leadership, initiated a violent campaign against them. This kind of campaign was later known as classicide,[84] though several international legislatures have passed resolutions declaring the campaign a genocide.[85] Some historians dispute that these social-class actions constitute genocide.[86][87][88]

Purges and executions

Middle: Stalin's handwriting: "за" (support)

Right: the Politburo's decision is signed by Stalin

As head of the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Stalin consolidated nearly absolute power in the 1930s with a Great Purge of the party that claimed to expel "opportunists" and "counter-revolutionary infiltrators".[89][90] Those targeted by the purge were often expelled from the party; more severe measures ranged from banishment to the Gulag labor camps to execution after trials held by NKVD troikas.[89][91][92]

In the 1930s, Stalin became increasingly worried about Leningrad party head Sergei Kirov's growing popularity. At the 1934 Party Congress, where the vote for the new Central Committee was held, Kirov received only three negative votes (the fewest of any candidate), while Stalin received over 100.[93][i] After Kirov's assassination, which Stalin may have orchestrated, Stalin invented a detailed scheme to implicate opposition leaders in the murder, including Trotsky, Lev Kamenev, and Grigory Zinoviev.[94] Thereafter, the investigations and trials expanded.[95] Stalin passed a new law on "terrorist organizations and terrorist acts" that were to be investigated for no more than ten days, with no prosecution, defense attorneys, or appeals, followed by a sentence to be imposed "quickly."[96] Stalin's Politburo also issued directives on quotas for mass arrests and executions.[97] Under Stalin, the death penalty was extended to adolescents as young as 12 years old in 1935.[98][99][100]

After that, several trials, known as the Moscow Trials, were held, but the procedures were replicated throughout the country. Article 58 of the legal code, which listed prohibited anti-Soviet activities as a counter-revolutionary crime, was applied most broadly.[101] Many alleged anti-Soviet pretexts were used to brand individuals as "enemies of the people", starting the cycle of public persecution, often proceeding to interrogation, torture, and deportation, if not death. The Russian word troika thereby gained a new meaning: a quick, simplified trial by a committee of three subordinated to the NKVD troika—with sentencing carried out within 24 hours.[96] Stalin's hand-picked executioner Vasili Blokhin was entrusted with carrying out some of the high-profile executions in this period.[102]

Many military leaders were convicted of treason, and a large-scale purge of Red Army officers followed.[ii] The repression of many formerly high-ranking revolutionaries and party members led Trotsky to claim that a "river of blood" separated Stalin's regime from Lenin's.[104] In August 1940, Trotsky was assassinated in Mexico, where he had lived in exile since January 1937. This eliminated the last of Stalin's opponents among the former Party leadership.[105]

Mass operations of the NKVD also targeted "national contingents" (foreign ethnicities) such as Poles, ethnic Germans, and Koreans. A total of 350,000 (144,000 of them Poles) were arrested and 247,157 (110,000 Poles) were executed.[106][page needed] Many Americans who had emigrated to the Soviet Union during the worst of the Great Depression were executed, while others were sent to prison camps or gulags.[107][108] Concurrent with the purges, efforts were made to rewrite the history in Soviet textbooks and other propaganda materials. Notable people executed by NKVD were removed from the texts and photographs as though they had never existed.

In light of revelations from Soviet archives, historians now estimate that nearly 700,000 people (353,074 in 1937 and 328,612 in 1938) were executed in the course of the terror,[109] the great mass of them ordinary Soviet citizens: workers, peasants, homemakers, teachers, priests, musicians, soldiers, pensioners, ballerinas, and beggars.[110][111]: 4 Scholars estimate the total death toll for the Great Purge (1936–1938) including fatalities attributed to imprisonment to be roughly 700,000-1.2 million.[112][113][114][115][116] Many of the executed were interred in mass graves, with some significant killing and burial sites being Bykivnia, Kurapaty, and Butovo.[117] Some Western experts believe the evidence released from the Soviet archives is understated, incomplete or unreliable.[118][119][120][121][122] Conversely, historian Stephen G. Wheatcroft, who spent much of his career researching the archives, contends that, before the collapse of the Soviet Union and the opening of the archives for historical research, "our understanding of the scale and the nature of Soviet repression has been extremely poor" and that some specialists who wish to maintain earlier high estimates of the Stalinist death toll are "finding it difficult to adapt to the new circumstances when the archives are open and when there are plenty of irrefutable data" and instead "hang on to their old Sovietological methods with round-about calculations based on odd statements from emigres and other informants who are supposed to have superior knowledge."[123][124]

Stalin personally signed 357 proscription lists in 1937 and 1938 that condemned 40,000 people to execution, about 90% of whom are confirmed to have been shot.[125] While reviewing one such list, he reportedly muttered to no one in particular: "Who's going to remember all this riff-raff in ten or twenty years? No one. Who remembers the names now of the boyars Ivan the Terrible got rid of? No one."[126] In addition, Stalin dispatched a contingent of NKVD operatives to Mongolia, established a Mongolian version of the NKVD troika, and unleashed a bloody purge in which tens of thousands were executed as "Japanese spies", as Mongolian ruler Khorloogiin Choibalsan closely followed Stalin's lead.[111]: 2 Stalin had ordered for 100,000 Buddhist lamas in Mongolia to be liquidated but the political leader Peljidiin Genden resisted the order.[127][128][129]

Under Stalinist influence in the Mongolian People's Republic, an estimated 17,000 monks were killed, official figures show.[130] Stalinist forces also oversaw purges of anti-Stalinist elements among the Spanish Republican insurgents, including the Trotskyist allied POUM faction and anarchist groups, during the Spainish Civil War.[131][132][133][134]

During the 1930s and 1940s, the Soviet leadership sent NKVD squads into other countries to murder defectors and opponents of the Soviet regime. Victims of such plots included Trotsky, Yevhen Konovalets, Ignace Poretsky, Rudolf Klement, Alexander Kutepov, Evgeny Miller, and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) leadership in Catalonia (e.g., Andréu Nin Pérez).[135] Joseph Berger-Barzilai, co-founder of the Communist Party of Palestine, spent twenty five years in Stalin's prisons and concentrations camps after the purges in 1937.[136][137]

Deportations

Shortly before, during, and immediately after World War II, Stalin conducted a series of deportations that profoundly affected the ethnic map of the Soviet Union. Separatism, resistance to Soviet rule, and collaboration with the invading Germans were the official reasons for the deportations. Individual circumstances of those spending time in German-occupied territories were not examined. After the brief Nazi occupation of the Caucasus, the entire population of five of the small highland peoples and the Crimean Tatars—more than a million people in total—were deported without notice or any opportunity to take their possessions.[138]

As a result of Stalin's lack of trust in the loyalty of particular ethnicities, groups such as the Soviet Koreans, Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Chechens, and many Poles, were forcibly moved out of strategic areas and relocated to places in the central Soviet Union, especially Kazakhstan. By some estimates, hundreds of thousands of deportees may have died en route.[139] It is estimated that between 1941 and 1949, nearly 3.3 million people[139][140] were deported to Siberia and the Central Asian republics. By some estimates, up to 43% of the resettled population died of diseases and malnutrition.[141]

According to official Soviet estimates, more than 14 million people passed through the gulags from 1929 to 1953, with a further 7 to 8 million deported and exiled to remote areas of the Soviet Union (including entire nationalities in several cases).[142] The emergent scholarly consensus is that from 1930 to 1953, around 1.5 to 1.7 million perished in the gulag system.[143][144][145] In February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev condemned the deportations as a violation of Leninism and reversed most of them, although it was not until 1991 that the Tatars, Meskhetians, and Volga Germans were allowed to return en masse to their homelands.

Economic policy

At the start of the 1930s, Stalin launched a wave of radical economic policies that completely overhauled the industrial and agricultural face of the Soviet Union. This became known as the Great Turn as Russia turned away from the mixed-economic type New Economic Policy (NEP) and adopted a planned economy. Lenin implemented the NEP to ensure the survival of the socialist state following seven years of war (World War I, 1914–1917, and the subsequent Civil War, 1917–1921) and rebuilt Soviet production to its 1913 levels. But Russia still lagged far behind the West, and Stalin and the majority of the Communist Party felt the NEP not only to be compromising communist ideals but also not delivering satisfactory economic performance or creating the envisaged socialist society.

According to historian Sheila Fitzpatrick, the scholarly consensus was that Stalin appropriated the position of the Left Opposition on such matters as industrialisation and collectivisation.[146] Trotsky maintained that the disproportions and imbalances which became characteristic of Stalinist planning in the 1930s such as the underdeveloped consumer base along with the priority focus on heavy industry were due to a number of avoidable problems. He argued that the industrial drive had been enacted under more severe circumstances, several years later and in a less rational manner than originally conceived by the Left Opposition.[147]

Fredric Jameson has said that "Stalinism was…a success and fulfilled its historic mission, socially as well as economically" given that it "modernized the Soviet Union, transforming a peasant society into an industrial state with a literate population and a remarkable scientific superstructure."[148] Robert Conquest disputes that conclusion, writing, "Russia had already been fourth to fifth among industrial economies before World War I", and that Russian industrial advances could have been achieved without collectivization, famine, or terror. According to Conquest, the industrial successes were far less than claimed, and the Soviet-style industrialization was "an anti-innovative dead-end."[149] Stephen Kotkin said those who argue collectivization was necessary are "dead wrong", writing that it "only seemed necessary within the straitjacket of Communist ideology and its repudiation of capitalism. And economically, collectivization failed to deliver." Kotkin further claimed that it decreased harvests instead of increasing them, as peasants tended to resist heavy taxes by producing fewer goods, caring only about their own subsistence.[150][151]: 5

According to several Western historians,[152] Stalinist agricultural policies were a key factor in the Soviet famine of 1930–1933; some scholars believe that Holodomor, which started near the end of 1932, was when the famine turned into an instrument of genocide; the Ukrainian government now recognizes it as such. Some scholars dispute the intentionality of the famine.[153][154]

Social issues

The Stalinist era was largely regressive on social issues. Despite a brief period of decriminalization under Lenin, the 1934 Criminal Code re-criminalized homosexuality.[155] Abortion was made illegal again in 1936[156] after controversial debate among citizens,[157] and women's issues were largely ignored.[158]

Relationship to Leninism

Stalin considered the political and economic system under his rule to be Marxism–Leninism, which he considered the only legitimate successor of Marxism and Leninism. The historiography of Stalin is diverse, with many different aspects of continuity and discontinuity between the regimes Stalin and Lenin proposed. Some historians, such as Richard Pipes, consider Stalinism the natural consequence of Leninism: Stalin "faithfully implemented Lenin's domestic and foreign policy programs."[159] Robert Service writes that "institutionally and ideologically Lenin laid the foundations for a Stalin [...] but the passage from Leninism to the worse terrors of Stalinism was not smooth and inevitable."[160] Likewise, historian and Stalin biographer Edvard Radzinsky believes that Stalin was a genuine follower of Lenin, exactly as he claimed.[161] Another Stalin biographer, Stephen Kotkin, wrote that "his violence was not the product of his subconscious but of the Bolshevik engagement with Marxist–Leninist ideology."[162]

Dmitri Volkogonov, who wrote biographies of both Lenin and Stalin, wrote that during the 1960s through 1980s, an official patriotic Soviet de-Stalinized view of the Lenin–Stalin relationship (during the Khrushchev Thaw and later) was that the overly autocratic Stalin had distorted the Leninism of the wise dedushka Lenin. But Volkogonov also lamented that this view eventually dissolved for those like him who had the scales fall from their eyes immediately before and after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. After researching the biographies in the Soviet archives, he came to the same conclusion as Radzinsky and Kotkin (that Lenin had built a culture of violent autocratic totalitarianism of which Stalinism was a logical extension).

Proponents of continuity cite a variety of contributory factors, such as that Lenin, not Stalin, introduced the Red Terror with its hostage-taking and internment camps, and that Lenin developed the infamous Article 58 and established the autocratic system in the Communist Party.[163] They also note that Lenin put a ban on factions within the Russian Communist Party and introduced the one-party state in 1921—a move that enabled Stalin to get rid of his rivals easily after Lenin's death and cite Felix Dzerzhinsky, who, during the Bolshevik struggle against opponents in the Russian Civil War, exclaimed: "We stand for organized terror—this should be frankly stated."[164]

Opponents of this view include revisionist historians and many post–Cold War and otherwise dissident Soviet historians, including Roy Medvedev, who argues that although "one could list the various measures carried out by Stalin that were actually a continuation of anti-democratic trends and measures implemented under Lenin…in so many ways, Stalin acted, not in line with Lenin's clear instructions, but in defiance of them."[165] In doing so, some historians have tried to distance Stalinism from Leninism to undermine the totalitarian view that Stalin's methods were inherent in communism from the start.[166] Other revisionist historians such as Orlando Figes, while critical of the Soviet era, acknowledge that Lenin actively sought to counter Stalin's growing influence, allying with Trotsky in 1922–23, opposing Stalin on foreign trade, and proposing party reforms including the democratization of the Central Committee and recruitment of 50-100 ordinary workers into the party's lower organs.[167]

Critics include anti-Stalinist communists such as Trotsky, who pointed out that Lenin attempted to persuade the Communist Party to remove Stalin from his post as its General Secretary.Trotsky also argued that he and Lenin had intended to lift the ban on the opposition parties such as the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries as soon as the economic and social conditions of Soviet Russia had improved.[168] Lenin's Testament, the document containing this order, was suppressed after Lenin's death. Various historians have cited Lenin's proposal to appoint Trotsky as a Vice-chairman of the Soviet Union as evidence that he intended Trotsky to be his successor as head of government.[169][170][171][172][173] In his biography of Trotsky, British historian Isaac Deutscher writes that, faced with the evidence, "only the blind and the deaf could be unaware of the contrast between Stalinism and Leninism."[174] Similarly, historian Moshe Lewin writes, "The Soviet regime underwent a long period of 'Stalinism,' which in its basic features was diametrically opposed to the recommendations of [Lenin's] testament".[175] French historian Pierre Broue disputes the historical assessments of the early Soviet Union by modern historians such as Dmitri Volkogonov, which Broue argues falsely equate Leninism, Stalinism and Trotskyism to present the notion of ideological continuity and reinforce the position of counter-communism.[176]

Some scholars have attributed the establishment of the one-party system in the Soviet Union to the wartime conditions imposed on Lenin's government;[177] others have highlighted the initial attempts to form a coalition government with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries.[178] According to historian Marcel Liebman, Lenin's wartime measures such as banning opposition parties was prompted by the fact that several political parties either took up arms against the new Soviet government, participated in sabotage, collaborated with the deposed Tsarists, or made assassination attempts against Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders.[179] Liebman also argues that the banning of parties under Lenin did not have the same repressive character as later bans enforced by Stalin's regime.[179] Several scholars have highlighted the socially progressive nature of Lenin's policies, such as universal education, healthcare, and equal rights for women.[180][181] Conversely, Stalin's regime reversed Lenin's policies on social matters such as sexual equality, legal restrictions on marriage, rights of sexual minorities, and protective legislation.[182] Historian Robert Vincent Daniels also views the Stalinist period as a counterrevolution in Soviet cultural life that revived patriotic propaganda, the Tsarist programme of Russification and traditional, military ranks that Lenin had criticized as expressions of "Great Russian chauvinism".[183] Daniels also regards Stalinism as an abrupt break with the Leninist period in terms of economic policies in which a deliberated, scientific system of economic planning that featured former Menshevik economists at Gosplan was replaced by a hasty version of planning with unrealistic targets, bureaucractic waste, bottlenecks and shortages.[184]

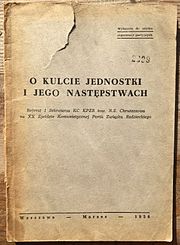

In his "Secret Speech", delivered in 1956, Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin's successor, argued that Stalin's regime differed profusely from the leadership of Lenin. He was critical of the cult of the individual constructed around Stalin whereas Lenin stressed "the role of the people as the creator of history".[185] He also emphasized that Lenin favored a collective leadership that relied on personal persuasion and recommended Stalin's removal as General Secretary. Khrushchev contrasted this with Stalin's "despotism", which required absolute submission to his position, and highlighted that many of the people later annihilated as "enemies of the party ... had worked with Lenin during his life".[185] He also contrasted the "severe methods" Lenin used in the "most necessary cases" as a "struggle for survival" during the Civil War with the extreme methods and mass repressions Stalin used even when the revolution was "already victorious".[185] In his memoirs, Khrushchev argued that his widespread purges of the "most advanced nucleus of people" among the Old Bolsheviks and leading figures in the military and scientific fields had "undoubtedly" weakened the nation.[186] According to Stalin's secretary, Boris Bazhanov, Stalin was jubilant over Lenin's death while "publicly putting on the mask of grief".[187]

Some Marxist theoreticians have disputed the view that Stalin's dictatorship was a natural outgrowth of the Bolsheviks' actions, as Stalin eliminated most of the original central committee members from 1917.[188] George Novack stressed the Bolsheviks' initial efforts to form a government with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and bring other parties such as the Mensheviks into political legality.[189] Tony Cliff argued the Bolshevik-Left Socialist Revolutionary coalition government dissolved the Constituent Assembly for several reasons. They cited the outdated voter rolls, which did not acknowledge the split among the Socialist Revolutionary party, and the assembly's conflict with the Congress of the Soviets as an alternative democratic structure.[190]

A similar analysis is present in more recent works, such as those of Graeme Gill, who argues that Stalinism was "not a natural flow-on of earlier developments; [it formed a] sharp break resulting from conscious decisions by leading political actors."[191] But Gill adds that "difficulties with the use of the term reflect problems with the concept of Stalinism itself. The major difficulty is a lack of agreement about what should constitute Stalinism."[192] Revisionist historians such as Sheila Fitzpatrick have criticized the focus on the upper levels of society and the use of Cold War concepts such as totalitarianism, which have obscured the reality of the system.[193]

Russian historian Vadim Rogovin writes, "Under Lenin, the freedom to express a real variety of opinions existed in the party, and in carrying out political decisions, consideration was given to the positions of not only the majority, but a minority in the party". He compared this practice with subsequent leadership blocs, which violated party tradition, ignored opponents' proposals, and expelled the Opposition from the party on falsified charges, culminating in the Moscow Trials of 1936–1938. According to Rogovin, 80-90% of the members of the Central Committee elected at the Sixth through the Seventeenth Congresses were killed.[194] The Right and Left Opposition have been held by some scholars as representing political alternatives to Stalinism despite their shared beliefs in Leninism due to their policy platforms which were at variance with Stalin. This ranged from areas related to economics, foreign policy and cultural matters.[195][196]

Legacy

In Western historiography, Stalin is considered one of the worst and most notorious figures in modern history.[197][198][199][200] Biographer and historian Isaac Deutscher highlighted the totalitarian character of Stalinism and its suppression of "socialist inspiration".[3]

Several scholars have derided Stalinism for fostering anti-intellectual, antisemitic and chauvinistic attitudes within the Soviet Union.[201][202][203] According to Marxist philosopher Helena Sheehan, his philosophical legacy is almost universally rated negatively with most Soviet sources considering his influence to have negatively impacted the creative development of Soviet philosophy.[204] Sheehan discussed omissions in his views on dialectics and noted that most Soviet philosophers rejected his characterization of Hegel's philosophy.[205]

Pierre du Bois argues that the cult of personality around Stalin was elaborately constructed to legitimize his rule. Many deliberate distortions and falsehoods were used.[206] The Kremlin refused access to archival records that might reveal the truth, and critical documents were destroyed. Photographs were altered and documents were invented.[207] People who knew Stalin were forced to provide "official" accounts to meet the ideological demands of the cult, especially as Stalin presented it in 1938 in Short Course on the History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), which became the official history.[208] Historian David L. Hoffmann sums up the consensus of scholars: "The Stalin cult was a central element of Stalinism, and as such, it was one of the most salient features of Soviet rule. [...] Many scholars of Stalinism cite the cult as integral to Stalin's power or as evidence of Stalin's megalomania."[209]

But after Stalin died in 1953, Khrushchev repudiated his policies and condemned his cult of personality in his Secret Speech to the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956, instituting de-Stalinization and relative liberalization, within the same political framework. Consequently, the world's communist parties that previously adhered to Stalinism, except the German Democratic Republic and the Socialist Republic of Romania, abandoned it and, to a greater or lesser degree, adopted Khrushchev's positions. The Chinese Communist Party chose to split from the Soviet Union, resulting in the Sino-Soviet split.

Maoism and Hoxhaism

Mao Zedong famously declared that Stalin was 70% good and 30% bad. Maoists criticized Stalin chiefly for his view that bourgeois influence within the Soviet Union was primarily a result of external forces, to the almost complete exclusion of internal forces, and his view that class contradictions ended after the basic construction of socialism. Mao also criticized Stalin's cult of personality and the excesses of the great purge. But Maoists praised Stalin for leading the Soviet Union and the international proletariat, defeating fascism in Germany, and his anti-revisionism.[210]

Taking the side of the Chinese Communist Party in the Sino-Soviet split, the People's Socialist Republic of Albania remained committed, at least theoretically, to its brand of Stalinism (Hoxhaism) for decades under the leadership of Enver Hoxha. Despite their initial cooperation against "revisionism", Hoxha denounced Mao as a revisionist, along with almost every other self-identified communist organization worldwide, resulting in the Sino-Albanian split. This effectively isolated Albania from the rest of the world, as Hoxha was hostile to both the pro-American and pro-Soviet spheres of influence and the Non-Aligned Movement under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito, whom Hoxha had also previously denounced.[211][212]

Trotskyism

Leon Trotsky always viewed Stalin as the "candidate for grave-digger of our party and the revolution" during the succession struggle.[213] American historian Robert Vincent Daniels viewed Trotsky and the Left Opposition as a critical alternative to the Stalin-Bukharin majority in a number of areas. Daniels stated that the Left Opposition would have prioritised industrialisation but never contemplated the "violent uprooting" employed by Stalin and contrasted most directly with Stalinism on the issue of party democratization and bureaucratization.[214] Trotsky also opposed the policy of forced collectivisation under Stalin and favoured a voluntary, gradual approach towards agricultural production[215][216] with greater tolerance for the rights of Soviet Ukrainians.[217][218]

Trotskyists argue that the Stalinist Soviet Union was neither socialist nor communist but a bureaucratized degenerated workers' state—that is, a non-capitalist state in which exploitation is controlled by a ruling caste that, although not owning the means of production and not constituting a social class in its own right, accrues benefits and privileges at the working class's expense. Trotsky believed that the Bolshevik Revolution must be spread all over the globe's working class, the proletarians, for world revolution. But after the failure of the revolution in Germany, Stalin reasoned that industrializing and consolidating Bolshevism in Russia would best serve the proletariat in the long run. The dispute did not end until Trotsky was murdered in his Mexican villa in 1940 by Stalinist assassin Ramón Mercader.[219] Max Shachtman, a principal Trotskyist theorist in the U.S., argued that the Soviet Union had evolved from a degenerated worker's state to a new mode of production called bureaucratic collectivism, whereby orthodox Trotskyists considered the Soviet Union an ally gone astray. Shachtman and his followers thus argued for the formation of a Third Camp opposed to the Soviet and capitalist blocs equally. By the mid-20th century, Shachtman and many of his associates, such as Social Democrats, USA, identified as social democrats rather than Trotskyists, while some ultimately abandoned socialism altogether and embraced neoconservatism. In the U.K., Tony Cliff independently developed a critique of state capitalism that resembled Shachtman's in some respects but retained a commitment to revolutionary communism.[220] Similarly, American Trotskyist David North drew attention to the fact that the generation of bureaucrats that rose to power under Stalin's tutelage presided over the Soviet Union's stagnation and breakdown.[221]

At a time when hundreds of thousands and millions of workers, especially in Germany, are departing from Communism, in part to fascism and in the main into the camp of indifferentism, thousands and tens of thousands of Social Democratic workers, under the impact of the self-same defeat, are evolving into the left, to the side of Communism. There cannot, however, even be talk of their accepting the hopelessly discredited Stalinist leadership.

—Trotsky's writings on Stalinism and fascism in 1933[222]

Trotskyist historian Vadim Rogovin believed Stalinism had "discredited the idea of socialism in the eyes of millions of people throughout the world". Rogovin also argued that the Left Opposition, led by Trotsky, was a political movement that "offered a real alternative to Stalinism, and that to crush this movement was the primary function of the Stalinist terror".[223] According to Rogovin, Stalin had destroyed thousands of foreign communists capable of leading socialist change in their respective, countries. He cited 600 active Bulgarian communists who perished in his prison camps along with the thousands of German communists whom Stalin handed over to the Gestapo after the signing of the German-Soviet pact. Rogovin further noted that 16 members of the Central Committee of the German Communist Party became victims of Stalinist terror. Repressive measures were also enforced upon the Hungarian, Yugoslav and other Polish Communist parties.[224] British historian Terence Brotherstone argued that the Stalin era had a profound effect on those attracted to Trotsky's ideas. Brotherstone described figures who emerged from the Stalinist parties as miseducated, which he said helped to block the development of Marxism.[225]

Other interpretations

Some historians and writers, such as Dietrich Schwanitz,[226] draw parallels between Stalinism and the economic policy of Tsar Peter the Great; Schwanitz in particular views Stalin as "a monstrous reincarnation" of him. Both men wanted Russia to leave the western European states far behind in terms of development. Some reviewers have considered Stalinism a form of "red fascism".[227] Fascist regimes ideologically opposed the Soviet Union, but some regarded Stalinism favorably for evolving Bolshevism into a form of fascism. Benito Mussolini saw Stalinism as having transformed Soviet Bolshevism into a Slavic fascism.[228]

British historian Michael Ellman writes that mass deaths from famines are not a "uniquely Stalinist evil", noting that famines and droughts have been a common occurrence in Russian history, including the Russian famine of 1921–22, which occurred before Stalin came to power. He also notes that famines were widespread worldwide in the 19th and 20th centuries in countries such as India, Ireland, Russia and China. Ellman compares the Stalinist regime's behavior vis-à-vis the Holodomor to that of the British government (toward Ireland and India) and the G8 in contemporary times, arguing that the G8 "are guilty of mass manslaughter or mass deaths from criminal negligence because of their not taking obvious measures to reduce mass deaths" and that Stalin's "behaviour was no worse than that of many rulers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries".[229]

David L. Hoffmann questions whether Stalinist practices of state violence derive from socialist ideology. Placing Stalinism in an international context, he argues that many forms of state interventionism the Stalinist government used, including social cataloguing, surveillance and concentration camps, predate the Soviet regime and originated outside of Russia. He further argues that technologies of social intervention developed in conjunction with the work of 19th-century European reformers and greatly expanded during World War I, when state actors in all the combatant countries dramatically increased efforts to mobilize and control their populations. According to Hoffman, the Soviet state was born at this moment of total war and institutionalized state intervention practices as permanent features.[230]

In The Mortal Danger: Misconceptions about Soviet Russia and the Threat to America, anti-communist and Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn argues that the use of the term Stalinism hides the inevitable effects of communism as a whole on human liberty. He writes that the concept of Stalinism was developed after 1956 by Western intellectuals to keep the communist ideal alive. But "Stalinism" was used as early as 1937, when Trotsky wrote his pamphlet Stalinism and Bolshevism.[231]

In two Guardian articles in 2002 and 2006, British journalist Seumas Milne wrote that the impact of the post–Cold War narrative that Stalin and Hitler were twin evils, equating communism's evils with those of Nazism, "has been to relativize the unique crimes of Nazism, bury those of colonialism and feed the idea that any attempt at radical social change will always lead to suffering, killing and failure."[232][233]

According to historian Eric D. Weitz, 60% of German exiles in the Soviet Union had been liquidated during the Stalinist terror and a higher proportion of the KPD Politburo membership had died in the Soviet Union than in Nazi Germany. Weitz also noted that hundreds of German citizens, most of them Communists, were handed over to the Gestapo by Stalin's administration.[234]

Public opinion

In modern Russia, public opinion of Stalin and the former Soviet Union has improved in recent years.[235] Levada Center had found that favorability of the Stalinist era has increased from 18% in 1996 to 40% in 2016 which had coincided with his rehabilitation by the Putin government for the purpose of social patriotism and militarisation efforts.[236] According to a 2015 Levada Center poll, 34% of respondents (up from 28% in 2007) say that leading the Soviet people to victory in World War II was such an outstanding achievement that it outweighed Stalin's mistakes.[237] A 2019 Levada Center poll showed that support for Stalin, whom many Russians saw as the victor in the Great Patriotic War,[238] reached a record high in the post-Soviet era, with 51% regarding him as a positive figure and 70% saying his reign was good for the country.[239]

Lev Gudkov, a sociologist at the Levada Center, said, "Vladimir Putin's Russia of 2012 needs symbols of authority and national strength, however controversial they may be, to validate the newly authoritarian political order. Stalin, a despotic leader responsible for mass bloodshed but also still identified with wartime victory and national unity, fits this need for symbols that reinforce the current political ideology."[240]

Some positive sentiments can also be found elsewhere in the former Soviet Union. A 2012 survey commissioned by the Carnegie Endowment found 38% of Armenians concurring that their country "will always have need of a leader like Stalin".[240][241] A 2013 survey by Tbilisi University found 45% of Georgians expressing "a positive attitude" toward Stalin.[242]

See also

- Anti-Stalinist left

- Bibliography of Stalinism and the Soviet Union

- Cybernetics in the Soviet Union

- Comparison of Nazism and Stalinism

- Foreign interventions by the Soviet Union

- Everyday Stalinism

- Leningrad Affair

- Juche

- Human rights in the Soviet Union

- Mass killings under communist regimes

- Political views of Joseph Stalin

- Soviet Empire

- Hoxhaism

- Stalin's Peasants

- Stalin Society

- Stalinist architecture

- State socialism

- Socialism in one country

- The Stalinist Legacy

References

Citations

- ^ Kershaw, Ian; Lewin, Moshe (April 28, 1997). Stalinism and Nazism: Dictatorships in Comparison. Cambridge University Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-521-56521-9.

- ^ Baratieri, Daniela; Edele, Mark; Finaldi, Giuseppe (October 8, 2013). Totalitarian Dictatorship: New Histories. Routledge. pp. 1–50. ISBN 978-1-135-04396-4.

- ^ a b Deutscher, Isaac (1967). Stalin: A Political Biography. Oxford University Press. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-14-020757-6.

- ^ Montefiore, Simon Sebag (May 27, 2010). Young Stalin. Orion. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-297-86384-7.

- ^ Krieger, Joel (2013). The Oxford Companion to Comparative Politics. OUP USA. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-19-973859-5.

- ^ Gill, Graeme; Gill, Graeme J. (July 18, 2002). The Origins of the Stalinist Political System. Cambridge University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-521-52936-5.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (1961). Stalin: A Political Biography (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-0-19-500273-7.

- ^ Plamper, Jan (January 17, 2012). The Stalin Cult: A Study in the Alchemy of Power. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16952-2.

- ^ Bottomore, Thomas (1991). A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-631-18082-1.

- ^ Kotkin 1997, p. 71, 81, 307.

- ^ Rossman, Jeffrey (2005). Worker Resistance Under Stalin: Class and Revolution on the Shop Floor. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01926-1.

- ^ Pons, Silvo; Service, Robert, eds. (2012). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton University Press. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-691-15429-9.

- ^ a b Service, Robert (2007). Comrades!: A History of World Communism. Harvard University Press. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-0-674-04699-3.

- ^ Greeley, Andrew, ed. (2009). Religion in Europe at the End of the Second Millennium: A Sociological Profile. Routledge. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-7658-0821-9.

- ^ Pons, Silvo; Service, Robert, eds. (2012). A Dictionary of 20th Century Communism. Princeton University Press. pp. 308–310. ISBN 978-0-691-15429-9.

- ^ Sawicky, Nicholas D. (December 20, 2013). The Holodomor: Genocide and National Identity (Education and Human Development Master's Theses). The College at Brockport: State University of New York. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2020 – via Digital Commons.

Scholars also disagree over what role the Soviet Union played in the tragedy. Some scholars point to Stalin as the mastermind behind the famine, due to his hatred of Ukrainians (Hosking, 1987). Others assert that Stalin did not actively cause the famine, but he knew about it and did nothing to stop it (Moore, 2012). Still other scholars argue that the famine was just an effect of the Soviet Union's push for rapid industrialization and a by-product of that was the destruction of the peasant way of life (Fischer, 1935). The final school of thought argues that the Holodomor was caused by factors beyond the control of the Soviet Union and Stalin took measures to reduce the effects of the famine on the Ukrainian people (Davies & Wheatcroft, 2006).

- ^ Kotkin 1997, p. 70-71.

- ^ Kotkin 1997, p. 70-79.

- ^ De Basily, N. (2017) [1938]. Russia Under Soviet Rule: Twenty Years of Bolshevik Experiment. Routledge Library Editions: Early Western Responses to Soviet Russia. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-61717-8. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

... vast sums were spent on importing foreign technical 'ideas' and on securing the services of alien experts. Foreign countries, again – American and Germany in particular – lent the U.S.S.R. active aid in drafting the plans for all the undertakings to be constructed. They supplied the Soviet Union with tens of thousands of engineers, mechanics, and supervisors. During the first Five-Year Plan, not a single plant was erected, nor was a new industry launched without the direct help of foreigners working on the spot. Without the importation of Western European and American objects, ideas, and men, the 'miracle in the East' would not have been realized, or, at least, not in so short a time.

- ^ "Communism". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Montefiore 2007, p. 352.

- ^ Service 2004, p. 357.

- ^ Sandle 1999, pp. 208–209.

- ^ a b Sandle 1999, p. 209.

- ^ Sandle 1999, p. 261.

- ^ Sandle 1999, p. 211.

- ^ Sandle 1999, p. 210.

- ^ a b Montefiore 2004, p. 164.

- ^ Gilbert, Felix; Large, David Clay (2008). The End of the European Era: 1890 to the Present (6th ed.). New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-393-93040-5.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (August 29, 2012). "The fake photographs that predate Photoshop". The Guardian. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

In a 1949 portrait, the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin is seen as a young man with Lenin. Stalin and Lenin were close friends, judging from this photograph. But it is doctored, of course. Two portraits have been sutured to sentimentalise Stalin's life and closeness to Lenin.

- ^ Suny, Ronald (1998). The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the Successor States. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 221.

- ^ On Finland, Poland etc., Deutscher, chapter 6 "Stalin during the Civil War", (p. 148 in the Swedish 1980 printing)

- ^ Sakwa, Richard (August 17, 2005). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union. Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-134-80602-7.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac. [1949] 1961. "The General Secretary." Pp. 221–29 in Stalin, A Political Biography (2nd ed.).

- ^ Vyshinsky, Andrey Yanuaryevich (1950). Speeches Delivered at the Fifth Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, September–October, 1950. Information Bulletin of the Embassy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. p. 76.

- ^ Volkogonov, Dmitriĭ Antonovich (1998). Autopsy for an Empire: The Seven Leaders who Built the Soviet Regime. Simon and Schuster. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-684-83420-7.

- ^ Kotkin, Stephen (2017). Stalin. Vol II, Waiting for Hitler, 1928–1941. London : Allen Lane. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7139-9945-7.

- ^ "Stalinism." Encyclopædia Britannica. [1998] 2020.

- ^ Price, Wayne. "The Abolition of the State" (PDF). Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ Rudelson, Justin Jon; Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam; Ben-Adam, Justin (1997). Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China's Silk Road. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10786-0.

- ^ Quoted in Peters 2012, p. 150. From Rosenthal, Mark M.; Iudin, Pavel F., eds. (1954). Kratkii filosofskii slovar [Short Philosophical Dictionary] (4th ed.). Moscow: Gospolitizdat. pp. 236–237.

- ^ Service, Robert (2005). Stalin: A Biography. Harvard University Press. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-674-01697-2.

- ^ Kemp-Welch, A. (July 27, 2016). Stalin and the Literary Intelligentsia, 1928–39. Springer. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-349-21447-1.

- ^ Vucinich, Alexander (2001). Einstein and Soviet Ideology. Stanford University Press. pp. 1–15, 90–120. ISBN 978-0-8047-4209-2.

- ^ Daniels, Robert Vincent (1985). Russia, the Roots of Confrontation. Harvard University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-674-77966-2.

- ^ Stanchevici, Dmitri (March 2, 2017). Stalinist Genetics: The Constitutional Rhetoric of T. D. Lysenko. Taylor & Francis. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-351-86445-9.

- ^ a b Zubok, Vladislav M. (February 1, 2009). A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-8078-9905-2.

- ^ Riehl, Nikolaus; Seitz, Frederick (1996). Stalin's Captive: Nikolaus Riehl and the Soviet Race for the Bomb. Chemical Heritage Foundation. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-8412-3310-2.

- ^ Harrison, Selig S. (December 8, 2015). India: The Most Dangerous Decades. Princeton University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-4008-7780-5.

- ^ Gerovitch, Slava (September 17, 2004). From Newspeak to Cyberspeak: A History of Soviet Cybernetics. MIT Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-262-57225-5.

- ^ Krylov, Anna I. (June 10, 2021). "The Peril of Politicizing Science". The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 12 (22): 5371–5376. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c01475. ISSN 1948-7185. PMID 34107688. S2CID 235392946.

- ^ Elizabeth Ann Weinberg, The Development of Sociology in the Soviet Union, Taylor & Francis, 1974, ISBN 0-7100-7876-5, Google Print, pp. 8–9

- ^ Ings, Simon (February 21, 2017). Stalin and the Scientists: A History of Triumph and Tragedy, 1905–1953. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. pp. 1–528. ISBN 978-0-8021-8986-8.

- ^ Ings, Simon (February 21, 2017). Stalin and the Scientists: A History of Triumph and Tragedy, 1905–1953. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. pp. 1–528. ISBN 978-0-8021-8986-8.

- ^ Avron, Arnon; Dershowitz, Nachum; Rabinovich, Alexander (February 8, 2008). Pillars of Computer Science: Essays Dedicated to Boris (Boaz) Trakhtenbrot on the Occasion of His 85th Birthday. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-540-78126-4.

- ^ Gregory, Paul R.; Stuart, Robert C. (1974). Soviet Economic Structure and Performance. Harper & Row. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-06-042509-8.

- ^ Salsburg, David (May 2002). The Lady Tasting Tea: How Statistics Revolutionized Science in the Twentieth Century. Macmillan. pp. 147–149. ISBN 978-0-8050-7134-4.

- ^ Wrinch, Pamela N. (1951). "Science and Politics in the U.S.S.R.: The Genetics Debate". World Politics. 3 (4): 486–519. doi:10.2307/2008893. ISSN 0043-8871. JSTOR 2008893. S2CID 146284128.

- ^ Birstein, Vadim J. (2013). The Perversion Of Knowledge: The True Story Of Soviet Science. Perseus Books Group. ISBN 978-0-7867-5186-0. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

Academician Schmalhausen, Professors Formozov and Sabinin, and 3,000 other biologists, victims of the August 1948 Session, lost their professional jobs because of their integrity and moral principles [...]

- ^ a b Soyfer, Valery N. (September 1, 2001). "The Consequences of Political Dictatorship for Russian Science". Nature Reviews Genetics. 2 (9): 723–729. doi:10.1038/35088598. PMID 11533721. S2CID 46277758.

- ^ Soĭfer, Valeriĭ. (1994). Lysenko and The Tragedy of Soviet Science. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2087-2.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (June 17, 2016). "The Scourge of Soviet Science". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Swedin, Eric G. (2005). Science in the Contemporary World : An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 168, 280. ISBN 978-1-85109-524-7.

- ^ Jones, Derek (December 1, 2001). Censorship: A World Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 2083. ISBN 978-1-136-79864-1.

- ^ Jones, Derek (December 1, 2001). Censorship: A World Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 2083. ISBN 978-1-136-79864-1.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (January 2, 2022). "Stalin, Falsifier in Chief: E. H. Carr and the Perils of Historical Research Introduction". Revolutionary Russia. 35 (1): 11–14. doi:10.1080/09546545.2022.2065740. ISSN 0954-6545.

- ^ Bailey, Sydney D. (1955). "Stalin's Falsification of History: The Case of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty". The Russian Review. 14 (1): 24–35. doi:10.2307/126074. ISSN 0036-0341.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (January 13, 2019). The Stalin School of Falsification. Pickle Partners Publishing. pp. vii-89. ISBN 978-1-78912-348-7.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (January 13, 2019). The Stalin School of Falsification. Pickle Partners Publishing. pp. vii-89. ISBN 978-1-78912-348-7.

- ^ Figes, Orlando (1997). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. Pimlico. p. 802.

- ^ Nicholas, Sian; O'Malley, Tom; Williams, Kevin (September 13, 2013). Reconstructing the Past: History in the Mass Media 1890–2005. Routledge. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-317-99684-2.

- ^ Nicholas, Sian; O'Malley, Tom; Williams, Kevin (September 13, 2013). Reconstructing the Past: History in the Mass Media 1890–2005. Routledge. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-317-99684-2.

- ^ Nicholas, Sian; O'Malley, Tom; Williams, Kevin (September 13, 2013). Reconstructing the Past: History in the Mass Media 1890–2005. Routledge. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-317-99684-2.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Sheila (February 6, 2023). The Shortest History of the Soviet Union. Pan Macmillan. p. 116. ISBN 978-93-90742-78-3.

- ^ a b c Pisch, Anita (2016). "Introduction". The Personality Cult of Stalin in Soviet Posters, 1929–1953. ANU Press: 1–48. ISBN 978-1-76046-062-4. JSTOR j.ctt1q1crzp.6.

- ^ Pisch, Anita (2016). "The rise of the Stalin personality cult". The personality cult of Stalin in Soviet posters, 1929–1953. ANU Press. pp. 87–190. ISBN 978-1-76046-062-4. JSTOR j.ctt1q1crzp.8.

- ^ Saxonberg, Steven (February 14, 2013). Transitions and Non-Transitions from Communism: Regime Survival in China, Cuba, North Korea, and Vietnam. Cambridge University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-107-02388-8.

- ^ Ree, Erik van (August 27, 2003). The Political Thought of Joseph Stalin: A Study in Twentieth Century Revolutionary Patriotism. Routledge. pp. 1–384. ISBN 978-1-135-78604-5.

- ^ Davies, Sarah; Harris, James (October 14, 2014). Stalin's World: Dictating the Soviet Order. Yale University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-300-18281-1.

- ^ Stone, Dan (May 17, 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Postwar European History. OUP Oxford. p. 465. ISBN 978-0-19-956098-1.

- ^ Claeys, Gregory (August 20, 2013). Encyclopedia of Modern Political Thought (set). CQ Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-5063-0836-4.

- ^ Zuehlke, Jeffrey. 2006. Joseph Stalin. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 63.

- ^ Sémelin, Jacques, and Stanley Hoffman. 2007. Purify and Destroy: The Political Uses of Massacre and Genocide. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 37.

- ^ "Worldwide Recognition of the Holodomor as Genocide". October 18, 2019.

- ^ Davies, Robert; Wheatcroft, Stephen (2009). The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia Volume 5: The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931–1933. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-230-27397-9. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ Tauger, Mark B. (2001). "Natural Disaster and Human Actions in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1933". The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies (1506): 1–65. doi:10.5195/CBP.2001.89. ISSN 2163-839X. Archived from the original on June 12, 2017.

- ^ Getty, J. Arch (2000). "The Future Did Not Work". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Figes, Orlando. 2007. The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia. ISBN 0-8050-7461-9.

- ^ Gellately 2007.

- ^ Kershaw, Ian, and Moshe Lewin. 1997. Stalinism and Nazism: Dictatorships in Comparison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56521-9. p. 300.

- ^ Kuper, Leo. 1982. Genocide: Its Political Use in the Twentieth Century. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03120-3.

- ^ Brackman 2001, p. 204.

- ^ Brackman 2001, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Brackman 2001, p. 207.

- ^ a b Overy 2004, p. 182.

- ^ Harris, James (July 11, 2013). The Anatomy of Terror: Political Violence under Stalin. OUP Oxford. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-19-965566-3.

- ^ Mccauley, Martin (September 13, 2013). Stalin and Stalinism: Revised 3rd Edition. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-317-86369-4.

- ^ Wright, Patrick (October 28, 2009). Iron Curtain: From Stage to Cold War. OUP Oxford. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-19-162284-7.

- ^ Boobbyer 2000, p. 160.

- ^ Tucker 1992, p. 456.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy. Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books, 2010. ISBN 0-465-00239-0 p. 137.

- ^ "Newseum: The Commissar Vanishes". Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ^ Tucker, Robert C. 1999. Stalinism: Essays in Historical Interpretation, (American Council of Learned Societies Planning Group on Comparative Communist Studies). Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0483-2. p. 5.

- ^ Overy 2004, p. 338.

- ^ Montefiore 2004.

- ^ Tzouliadis, Tim. August 2, 2008.) "Nightmare in the workers paradise." BBC.

- ^ Tzouliadis, Tim. 2008. The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin's Russia. Penguin Press, ISBN 1-59420-168-4.

- ^ McLoughlin, Barry; McDermott, Kevin, eds. (2002). Stalin's Terror: High Politics and Mass Repression in the Soviet Union. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-4039-0119-4.

- ^ McLoughlin, Barry; McDermott, Kevin, eds. (2002). Stalin's Terror: High Politics and Mass Repression in the Soviet Union. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4039-0119-4.

- ^ a b Kuromiya, Hiroaki. 2007. The Voices of the Dead: Stalin's Great Terror in the 1930s. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-12389-2.

- ^ "Introduction: the Great Purges as history", Origins of the Great Purges, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–9, 1985, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511572616.002, ISBN 978-0-521-25921-7, retrieved December 2, 2021

- ^ Homkes, Brett (2004). "Certainty, Probability, and Stalin's Great Purge". McNair Scholars Journal.

- ^ Ellman, Michael (2002). "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments". Europe-Asia Studies. 54 (7): 1151–1172. ISSN 0966-8136.

- ^ Shearer, David R. (September 11, 2023). Stalin and War, 1918–1953: Patterns of Repression, Mobilization, and External Threat. Taylor & Francis. p. vii. ISBN 978-1-00-095544-6.

- ^ Nelson, Todd H. (October 16, 2019). Bringing Stalin Back In: Memory Politics and the Creation of a Useable Past in Putin’s Russia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-4985-9153-9.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2010) Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-00239-0 p. 101.

- ^ Rosefielde, Stephen (1996). "Stalinism in Post-Communist Perspective: New Evidence on Killings, Forced Labour and Economic Growth in the 1930s" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 48 (6): 959. doi:10.1080/09668139608412393.

- ^ Comment on Wheatcroft by Robert Conquest, 1999.

- ^ Pipes, Richard (2003) Communism: A History (Modern Library Chronicles), p. 67. ISBN 0-8129-6864-6.

- ^ Applebaum 2003, p. 584.

- ^ Keep, John (1997). "Recent Writing on Stalin's Gulag: An Overview". Crime, Histoire & Sociétés. 1 (2): 91–112. doi:10.4000/chs.1014.

- ^ Wheatcroft, S. G. (1996). "The Scale and Nature of German and Soviet Repression and Mass Killings, 1930–45" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 48 (8): 1319–53. doi:10.1080/09668139608412415. JSTOR 152781.

- ^ Wheatcroft, S. G. (2000). "The Scale and Nature of Stalinist Repression and its Demographic Significance: On Comments by Keep and Conquest" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 52 (6): 1143–59. doi:10.1080/09668130050143860. PMID 19326595. S2CID 205667754.

- ^ Ellman, Michael (2007). "Stalin and the Soviet Famine of 1932–33 Revisited". Europe-Asia Studies. 59 (4): 663–93. doi:10.1080/09668130701291899. S2CID 53655536. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2007. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Volkogonov, Dmitri. 1991. Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy. New York. p. 210. ISBN 0-7615-0718-3.

- ^ Baabar, Bat-Ėrdėniĭn (1999). History of Mongolia. Monsudar Pub. p. 322. ISBN 978-99929-0-038-3.

- ^ Kotkin, Stephen; Elleman, Bruce Allen (February 12, 2015). Mongolia in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-317-46010-7.

- ^ Dashpu̇rėv, Danzankhorloogiĭn; Soni, Sharad Kumar (1992). Reign of Terror in Mongolia, 1920–1990. South Asian Publishers. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-881318-15-6.

- ^ Thomas, Natalie (June 4, 2018). "Young monks lead revival of Buddhism in Mongolia after years of repression". Reuters. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ Sakwa, Richard (November 12, 2012). Soviet Politics: In Perspective. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-134-90996-4.

- ^ Whitehead, Jonathan (April 4, 2024). The End of the Spanish Civil War: Alicante 1939. Pen and Sword History. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-399-06395-1.

- ^ Service, Robert (2007). Comrades!: A History of World Communism. Harvard University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-674-02530-1.

- ^ Kocho-Williams, Alastair (January 4, 2013). Russia's International Relations in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-136-15747-9.

- ^ Ellman, Michael (2005). "The Role of Leadership Perceptions and of Intent in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1934" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 57 (6): 826. doi:10.1080/09668130500199392. S2CID 13880089. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2014.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (January 5, 2015). The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky. Verso Books. p. 1443. ISBN 978-1-78168-721-5.

- ^ Wasserstein, Bernard (May 2012). On the Eve: The Jews of Europe Before the Second World War. Simon and Schuster. p. 395. ISBN 978-1-4165-9427-7.

- ^ Bullock 1962, pp. 904–906.

- ^ a b Boobbyer 2000, p. 130.

- ^ Pohl, Otto, Ethnic Cleansing in the USSR, 1937–1949, ISBN 0-313-30921-3.

- ^ "Soviet Transit, Camp, and Deportation Death Rates". Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- ^ Conquest, Robert (1997). "Victims of Stalinism: A Comment". Europe-Asia Studies. 49 (7): 1317–1319. doi:10.1080/09668139708412501.

We are all inclined to accept the Zemskov totals (even if not as complete) with their 14 million intake to Gulag 'camps' alone, to which must be added 4–5 million going to Gulag 'colonies', to say nothing of the 3.5 million already in, or sent to, 'labour settlements'. However taken, these are surely 'high' figures.

- ^ Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (1999). "Victims of Stalinism and the Soviet Secret Police: The Comparability and Reliability of the Archival Data. Not the Last Word" (PDF). Europe-Asia Studies. 51 (2): 315–345. doi:10.1080/09668139999056.

- ^ Rosefielde, Steven. 2009. Red Holocaust. Routledge, 2009. ISBN 0-415-77757-7. pg. 67: "[M]ore complete archival data increases camp deaths by 19.4 percent to 1,258,537"; pg 77: "The best archivally based estimate of Gulag excess deaths at present is 1.6 million from 1929 to 1953."

- ^ Healey, Dan. 2018. "Golfo Alexopoulos. 'Illness and Inhumanity in Stalin's Gulag'" (review). American Historical Review 123(3):1049–51. doi:10.1093/ahr/123.3.1049.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Sheila (April 22, 2010). "The Old Man". London Review of Books. 32 (8). ISSN 0260-9592.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (January 5, 2015). The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky. Verso Books. p. 1141. ISBN 978-1-78168-721-5.

- ^ Fredric Jameson. Marxism Beyond Marxism (1996). p. 43. ISBN 0-415-91442-6.

- ^ Robert Conquest. Reflections on a Ravaged Century (2000). p. 101. ISBN 0-393-04818-7.

- ^ Kotkin 2014, p. 724–725.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Sheila (1994). Stalin's peasants : resistance and survival in the Russian village after collectivization. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506982-X. OCLC 28293091.

- ^ "Genocide in the 20th century". History Place.

- ^ Davies, Robert; Wheatcroft, Stephen (2009). The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia Volume 5: The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931–1933. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-230-27397-9.

- ^ Tauger, Mark B. (2001). "Natural Disaster and Human Actions in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1933". The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies (1506): 1–65. doi:10.5195/CBP.2001.89. ISSN 2163-839X. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017.

- ^ "1917 Russian Revolution: The gay community's brief window of freedom". BBC News. November 10, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ "When Soviet Women Won the Right to Abortion (For the Second Time)". jacobin.com. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ "Letters to the Editor on the Draft Abortion Law". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. August 31, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Mamonova, Tatyana (1984). Women and Russia: Feminist Writings from the Soviet Union. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Publisher. ISBN 0-631-13889-7.

- ^ Pipes, Richard. Three Whys of the Russian Revolution. pp. 83–4.

- ^ "Lenin: Individual and Politics in the October Revolution". Modern History Review. 2 (1): 16–19. 1990.

- ^ Edvard Radzinsky Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives, Anchor, (1997) ISBN 0-385-47954-9.

- ^ Anne Applebaum (October 14, 2014). "Understanding Stalin". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ Pipes, Richard (2001). Communism: A History. Random House Publishing. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-0-8129-6864-4.

- ^ George Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin's Political Police.

- ^ Roy Medvedev, Leninism and Western Socialism, Verso, 1981.

- ^ Moshe Lewin, Lenin's Last Testament, University of Michigan Press, 2005.

- ^ Figes, Orlando (1997). A people's tragedy : a history of the Russian Revolution. New York, NY : Viking. pp. 796–801. ISBN 978-0-670-85916-0.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (January 5, 2015). The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky. Verso Books. p. 528. ISBN 978-1-78168-721-5.

- ^ Danilov, Victor; Porter, Cathy (1990). "We Are Starting to Learn about Trotsky". History Workshop (29): 136–146. ISSN 0309-2984. JSTOR 4288968.

- ^ Daniels, Robert V. (October 1, 2008). The Rise and Fall of Communism in Russia. Yale University Press. p. 438. ISBN 978-0-300-13493-3.

- ^ Watson, Derek (July 27, 2016). Molotov and Soviet Government: Sovnarkom, 1930–41. Springer. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-349-24848-3.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (1965). The prophet unarmed: Trotsky, 1921–1929. New York, Vintage Books. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-394-70747-1.

- ^ Dziewanowski, M. K. (2003). Russia in the twentieth century. Upper Saddle River, N.J. : Prentice Hall. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-13-097852-3.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (1959). Trotsky: The Prophet Unarmed. pp. 464–5.

- ^ Lewin, Moshe (May 4, 2005). Lenin's Last Struggle. University of Michigan Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-472-03052-1.

- ^ Broue., Pierre (1992). Trotsky: a biographer's problems. In The Trotsky reappraisal. Brotherstone, Terence; Dukes, Paul,(eds). Edinburgh University Press. pp. 19, 20. ISBN 978-0-7486-0317-6.

- ^ Rogovin, Vadim Zakharovich (2021). Was There an Alternative? Trotskyism: a Look Back Through the Years. Mehring Books. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-1-893638-97-6.

- ^ Carr, Edward Hallett (1977). The Bolshevik revolution 1917–1923. Vol. 1 (Reprinted ed.). Penguin books. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-14-020749-1.

- ^ a b Liebman, Marcel (1985). Leninism Under Lenin. Merlin Press. pp. 1–348. ISBN 978-0-85036-261-9.

- ^ Adams, Katherine H.; Keene, Michael L. (January 10, 2014). After the Vote Was Won: The Later Achievements of Fifteen Suffragists. McFarland. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-7864-5647-5.

- ^ Ugri͡umov, Aleksandr Leontʹevich (1976). Lenin's Plan for Building Socialism in the USSR, 1917–1925. Novosti Press Agency Publishing House. p. 48.

- ^ Meade, Teresa A.; Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. (April 15, 2008). A Companion to Gender History. John Wiley & Sons. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-470-69282-0.

- ^ Daniels, Robert V. (November 2002). The End of the Communist Revolution. Routledge. pp. 90–94. ISBN 978-1-134-92607-7.

- ^ Daniels, Robert V. (November 2002). The End of the Communist Revolution. Routledge. pp. 90–92. ISBN 978-1-134-92607-7.

- ^ a b c Khrushchev, Nikita Sergeevich (1956). The Crimes Of The Stalin Era, Special Report To The 20th Congress Of The Communist Party Of The Soviet Union. pp. 1–65.