Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn | |

|---|---|

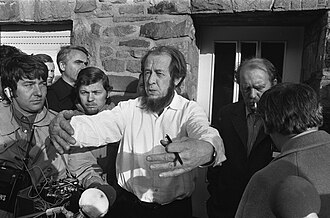

Solzhenitsyn in 1974 | |

| Native name | Александр Исаевич Солженицын |

| Born | 11 December 1918 Kislovodsk, Russian SFSR |

| Died | 3 August 2008 (aged 89) Moscow, Russia |

| Occupation |

|

| Citizenship | |

| Alma mater | Rostov State University |

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouses | Natalia Alekseyevna Reshetovskaya

(m. 1940; div. 1952)

(m. 1957; div. 1972)Natalia Dmitrievna Svetlova

(m. 1973) |

| Children |

|

| Signature | |

| |

| Website | |

| solzhenitsyn | |

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn[a][b] (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008)[6][7] was a Russian author and Soviet dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag prison system. He was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature "for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature".[8] His non-fiction work The Gulag Archipelago "amounted to a head-on challenge to the Soviet state" and sold tens of millions of copies.[9]

Solzhenitsyn was born into a family that defied the Soviet anti-religious campaign in the 1920s and remained devout members of the Russian Orthodox Church. However, he initially lost his faith in Christianity, became an atheist, and embraced Marxism–Leninism. While serving as a captain in the Red Army during World War II, Solzhenitsyn was arrested by SMERSH and sentenced to eight years in the Gulag and then internal exile for criticizing Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in a private letter. As a result of his experience in prison and the camps, he gradually became a philosophically minded Eastern Orthodox Christian.

As a result of the Khrushchev Thaw, Solzhenitsyn was released and exonerated. He pursued writing novels about repression in the Soviet Union and his experiences. In 1962, he published his first novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich—an account of Stalinist repressions—with approval from Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. His last work to be published in the Soviet Union was Matryona's Place in 1963. Following the removal of Khrushchev from power, the Soviet authorities attempted to discourage Solzhenitsyn from continuing to write. He continued to work on further novels and their publication in other countries including Cancer Ward in 1966, In the First Circle in 1968, August 1914 in 1971 and The Gulag Archipelago—which outraged the Soviet authorities—in 1973. In 1974, he was stripped of his Soviet citizenship and flown to West Germany.[10] He moved to the United States with his family in 1976 and continued to write there. His Soviet citizenship was restored in 1990. He returned to Russia four years later and remained there until his death in 2008.

Solzhenitsyn was born in Kislovodsk (now in Stavropol Krai, Russia). His father, Isaakiy Semyonovich Solzhenitsyn, was of Russian descent and his mother, Taisiya Zakharovna (née Shcherbak), was of Ukrainian descent.[11] Taisiya's father had risen from humble beginnings to become a wealthy landowner, acquiring a large estate in the Kuban region in the northern foothills of the Caucasus[12] and during World War I, Taisiya had gone to Moscow to study. While there she met and married Isaakiy, a young officer in the Imperial Russian Army of Cossack origin and fellow native of the Caucasus region. The family background of his parents is vividly brought to life in the opening chapters of August 1914, and in the later Red Wheel novels.[13]

In 1918, Taisiya became pregnant with Aleksandr. On 15 June, shortly after her pregnancy was confirmed, Isaakiy was killed in a hunting accident. Aleksandr was raised by his widowed mother and his aunt in lowly circumstances. His earliest years coincided with the Russian Civil War. By 1930 the family property had been turned into a collective farm. Later, Solzhenitsyn recalled that his mother had fought for survival and that they had to keep his father's background in the old Imperial Army a secret. His educated mother encouraged his literary and scientific learnings and raised him in the Russian Orthodox faith;[14][15] she died in 1944 having never remarried.[16]

As early as 1936, Solzhenitsyn began developing the characters and concepts for planned epic work on World War I and the Russian Revolution. This eventually led to the novel August 1914; some of the chapters he wrote then still survive.[citation needed] Solzhenitsyn studied mathematics and physics at Rostov State University. At the same time, he took correspondence courses from the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature, and History, which by this time were heavily ideological in scope. As he himself makes clear, he did not question the state ideology or the superiority of the Soviet Union until he was sentenced to time in the camps.[17]

During the war, Solzhenitsyn served as the commander of a sound-ranging battery in the Red Army,[18] was involved in major action at the front, and was twice decorated. He was awarded the Order of the Red Star on 8 July 1944 for sound-ranging two German artillery batteries and adjusting counterbattery fire onto them, resulting in their destruction.[19]

A series of writings published late in his life, including the early uncompleted novel Love the Revolution!, chronicle his wartime experience and growing doubts about the moral foundations of the Soviet regime.[20]

While serving as an artillery officer in East Prussia, Solzhenitsyn witnessed war crimes against local German civilians by Soviet military personnel. Of the atrocities, Solzhenitsyn wrote: "You know very well that we've come to Germany to take our revenge" for Nazi atrocities committed in the Soviet Union.[21] The noncombatants and the elderly were robbed of their meager possessions and women and girls were gang-raped. A few years later, in the forced labor camp, he memorized a poem titled "Prussian Nights" about a woman raped to death in East Prussia. In this poem, which describes the gang-rape of a Polish woman whom the Red Army soldiers mistakenly thought to be a German,[22] the first-person narrator comments on the events with sarcasm and refers to the responsibility of official Soviet writers like Ilya Ehrenburg.

In The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn wrote, "There is nothing that so assists the awakening of omniscience within us as insistent thoughts about one's own transgressions, errors, mistakes. After the difficult cycles of such ponderings over many years, whenever I mentioned the heartlessness of our highest-ranking bureaucrats, the cruelty of our executioners, I remember myself in my Captain's shoulder boards and the forward march of my battery through East Prussia, enshrouded in fire, and I say: 'So were we any better?'"[23]

In February 1945, while serving in East Prussia, Solzhenitsyn was arrested by SMERSH for writing derogatory comments in private letters to a friend, Nikolai Vitkevich,[24] about the conduct of the war by Joseph Stalin, whom he called "Khozyain" ("the boss"), and "Balabos" (Yiddish rendering of Hebrew baal ha-bayit for "master of the house").[25] He also had talks with the same friend about the need for a new organization to replace the Soviet regime.[26][clarification needed]

Solzhenitsyn was accused of anti-Soviet propaganda under Article 58, paragraph 10 of the Soviet criminal code, and of "founding a hostile organization" under paragraph 11.[27][28] Solzhenitsyn was taken to the Lubyanka prison in Moscow, where he was interrogated. On 9 May 1945, it was announced that Germany had surrendered and all of Moscow broke out in celebrations with fireworks and searchlights illuminating the sky to celebrate the victory in the Great Patriotic War. From his cell in the Lubyanka, Solzhenitsyn remembered: "Above the muzzle of our window, and from all the other cells of the Lubyanka, and from all the windows of the Moscow prisons, we too, former prisoners of war and former front-line soldiers, watched the Moscow heavens, patterned with fireworks and crisscrossed with beams of searchlights. There was no rejoicing in our cells and no hugs and no kisses for us. That victory was not ours."[29] On 7 July 1945, he was sentenced in his absence by Special Council of the NKVD to an eight-year term in a labour camp. This was the usual sentence for most crimes under Article 58 at the time.[30]

The first part of Solzhenitsyn's sentence was served in several work camps; the "middle phase", as he later referred to it, was spent in a sharashka (a special scientific research facility run by Ministry of State Security), where he met Lev Kopelev, upon whom he based the character of Lev Rubin in his book The First Circle, published in a self-censored or "distorted" version in the West in 1968 (an English translation of the full version was eventually published by Harper Perennial in October 2009).[31] In 1950, Solzhenitsyn was sent to a "Special Camp" for political prisoners. During his imprisonment at the camp in the town of Ekibastuz in Kazakhstan, he worked as a miner, bricklayer, and foundry foreman. His experiences at Ekibastuz formed the basis for the book One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. One of his fellow political prisoners, Ion Moraru, remembers that Solzhenitsyn spent some of his time at Ekibastuz writing.[32] While there, Solzhenitsyn had a tumor removed. His cancer was not diagnosed at the time.

In March 1953, after his sentence ended, Solzhenitsyn was sent to internal exile for life at Birlik,[33] a village in Baidibek District of South Kazakhstan.[34] His undiagnosed cancer spread until, by the end of the year, he was close to death. In 1954, Solzhenitsyn was permitted to be treated in a hospital in Tashkent, where his tumor went into remission. His experiences there became the basis of his novel Cancer Ward and also found an echo in the short story "The Right Hand."

It was during this decade of imprisonment and exile that Solzhenitsyn developed the philosophical and religious positions of his later life, gradually becoming a philosophically minded Eastern Orthodox Christian as a result of his experience in prison and the camps.[35][36][37] He repented for some of his actions as a Red Army captain, and in prison compared himself to the perpetrators of the Gulag. His transformation is described at some length in the fourth part of The Gulag Archipelago ("The Soul and Barbed Wire"). The narrative poem The Trail (written without benefit of pen or paper in prison and camps between 1947 and 1952) and the 28 poems composed in prison, forced-labour camp, and exile also provide crucial material for understanding Solzhenitsyn's intellectual and spiritual odyssey during this period. These "early" works, largely unknown in the West, were published for the first time in Russian in 1999 and excerpted in English in 2006.[38][39]

On 7 April 1940, while at the university, Solzhenitsyn married Natalia Alekseevna Reshetovskaya.[40] They had just over a year of married life before he went into the army, then to the Gulag. They divorced in 1952, a year before his release because the wives of Gulag prisoners faced the loss of work or residence permits. After the end of his internal exile, they remarried in 1957,[41] divorcing a second time in 1972. Reshetovskaya wrote negatively of Solzhenitsyn in her memoirs, accusing him of having affairs, and said of the relationship that "[Solzhenitsyn]'s despotism ... would crush my independence and would not permit my personality to develop."[42] In her 1974 memoir, Sanya: My Life with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, she wrote that she was "perplexed" that the West had accepted The Gulag Archipelago as "the solemn, ultimate truth", saying its significance had been "overestimated and wrongly appraised". Pointing out that the book's subtitle is "An Experiment in Literary Investigation", she said that her husband did not regard the work as "historical research, or scientific research". She contended that it was, rather, a collection of "camp folklore", containing "raw material" which her husband was planning to use in his future productions.

In 1973, Solzhenitsyn married his second wife, Natalia Dmitrievna Svetlova, a mathematician who had a son, Dmitri Turin, from a brief prior marriage.[43] He and Svetlova (born 1939) had three sons: Yermolai (1970), Ignat (1972), and Stepan (1973).[44] Dmitri Turin died on 18 March 1994, aged 32, at his home in New York City.[45]

After Khrushchev's Secret Speech in 1956, Solzhenitsyn was freed from exile and exonerated. Following his return from exile, Solzhenitsyn was, while teaching at a secondary school during the day, spending his nights secretly engaged in writing. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech he wrote that "during all the years until 1961, not only was I convinced I should never see a single line of mine in print in my lifetime, but, also, I scarcely dared allow any of my close acquaintances to read anything I had written because I feared this would become known."[46]

In 1960, aged 42, Solzhenitsyn approached Aleksandr Tvardovsky, a poet and the chief editor of the Novy Mir magazine, with the manuscript of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. It was published in edited form in 1962, with the explicit approval of Nikita Khrushchev, who defended it at the presidium of the Politburo hearing on whether to allow its publication, and added: "There's a Stalinist in each of you; there's even a Stalinist in me. We must root out this evil."[47] The book quickly sold out and became an instant hit.[48] In the 1960s, while Solzhenitsyn was publicly known to be writing Cancer Ward, he was simultaneously writing The Gulag Archipelago. During Khrushchev's tenure, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was studied in schools in the Soviet Union, as were three more short works of Solzhenitsyn's, including his short story "Matryona's Home", published in 1963. These would be the last of his works published in the Soviet Union until 1990.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich brought the Soviet system of prison labour to the attention of the West. It caused as much of a sensation in the Soviet Union as it did in the West—not only by its striking realism and candour, but also because it was the first major piece of Soviet literature since the 1920s on a politically charged theme, written by a non-party member, indeed a man who had been to Siberia for "libelous speech" about the leaders, and yet its publication had been officially permitted. In this sense, the publication of Solzhenitsyn's story was an almost unheard of instance of free, unrestrained discussion of politics through literature. However, after Khrushchev had been ousted from power in 1964, the time for such raw, exposing works came to an end.[48]

Every time when we speak about Solzhenitsyn as the enemy of the Soviet regime, this just happens to coincide with some important [international] events and we postpone the decision.

— Andrei Kirilenko, a Politburo member

Solzhenitsyn made an unsuccessful attempt, with the help of Tvardovsky, to have his novel Cancer Ward legally published in the Soviet Union. This required the approval of the Union of Writers. Though some there appreciated it, the work was ultimately denied publication unless it was to be revised and cleaned of suspect statements and anti-Soviet insinuations.[49]

After Khrushchev's removal in 1964, the cultural climate again became more repressive. Publishing of Solzhenitsyn's work quickly stopped; as a writer, he became a non-person, and, by 1965, the KGB had seized some of his papers, including the manuscript of In The First Circle. Meanwhile, Solzhenitsyn continued to secretly and feverishly work on the most well-known of his writings, The Gulag Archipelago. The seizing of his novel manuscript first made him desperate and frightened, but gradually he realized that it had set him free from the pretenses and trappings of being an "officially acclaimed" writer, a status which had become familiar but which was becoming increasingly irrelevant.

After the KGB had confiscated Solzhenitsyn's materials in Moscow, in the years 1965 to 1967, the preparatory drafts of The Gulag Archipelago were turned into finished typescript in hiding at his friends' homes in Soviet Estonia. Solzhenitsyn had befriended Arnold Susi, a lawyer and former Minister of Education of Estonia in a Lubyanka Building prison cell. After completion, Solzhenitsyn's original handwritten script was kept hidden from the KGB in Estonia by Arnold Susi's daughter Heli Susi until the collapse of the Soviet Union.[50][51]

In 1969, Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Union of Writers. In 1970, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He could not receive the prize personally in Stockholm at that time, since he was afraid he would not be let back into the Soviet Union. Instead, it was suggested he should receive the prize in a special ceremony at the Swedish embassy in Moscow. The Swedish government refused to accept this solution because such a ceremony and the ensuing media coverage might upset the Soviet Union and damage Swedish-Soviet relations. Instead, Solzhenitsyn received his prize at the 1974 ceremony after he had been expelled from the Soviet Union. In 1973, another manuscript written by Solzhenitsyn was confiscated by the KGB after his friend Elizaveta Voronyanskaya was questioned non-stop for five days until she revealed its location, according to a statement by Solzhenitsyn to Western reporters on September 6, 1973. According to Solzhenitsyn, "When she returned home, she hanged herself."[52]

The Gulag Archipelago was composed from 1958 to 1967, and has sold over thirty million copies in thirty-five languages. It was a three-volume, seven-part work on the Soviet prison camp system, which drew from Solzhenitsyn's experiences and the testimony of 256[53] former prisoners and Solzhenitsyn's own research into the history of the Russian penal system. It discusses the system's origins from the founding of the Communist regime, with Vladimir Lenin having responsibility, detailing interrogation procedures, prisoner transports, prison camp culture, prisoner uprisings and revolts such as the Kengir uprising, and the practice of internal exile. Soviet and Communist studies historian and archival researcher Stephen G. Wheatcroft wrote that the book was essentially a "literary and political work", and "never claimed to place the camps in a historical or social-scientific quantitative perspective" but that in the case of qualitative estimates, Solzhenitsyn gave his high estimate as he wanted to challenge the Soviet authorities to show that "the scale of the camps was less than this."[54] Historian J. Arch Getty wrote of Solzhenitsyn's methodology that "such documentation is methodically unacceptable in other fields of history",[55] which gives priority to vague hearsay and leads towards selective bias.[56] According to journalist Anne Applebaum, who has made extensive research on the Gulag, The Gulag Archipelago's rich and varied authorial voice, its unique weaving together of personal testimony, philosophical analysis, and historical investigation, and its unrelenting indictment of Communist ideology made it one of the most influential books of the 20th century.[57]

On 8 August 1971, the KGB allegedly attempted to assassinate Solzhenitsyn using an unknown chemical agent (most likely ricin) with an experimental gel-based delivery method.[58][59] The attempt left him seriously ill, but he survived.[60][61]

Although The Gulag Archipelago was not published in the Soviet Union, it was extensively criticized by the Party-controlled Soviet press. An editorial in Pravda on 14 January 1974 accused Solzhenitsyn of supporting "Hitlerites" and making "excuses for the crimes of the Vlasovites and Bandera gangs." According to the editorial, Solzhenitsyn was "choking with pathological hatred for the country where he was born and grew up, for the socialist system, and for Soviet people."[62]

During this period, he was sheltered by the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, who suffered considerably for his support of Solzhenitsyn and was eventually forced into exile himself.[63]

In a discussion of its options in dealing with Solzhenitsyn, the members of the Politburo considered his arrest and imprisonment and his expulsion to a capitalist country willing to take him.[64] Guided by KGB chief Yuri Andropov, and following a statement from West German Chancellor Willy Brandt that Solzhenitsyn could live and work freely in West Germany, it was decided to deport the writer directly to that country.[65]

On 12 February 1974, Solzhenitsyn was arrested and deported the next day from the Soviet Union to Frankfurt, West Germany and stripped of his Soviet citizenship.[66] The KGB had found the manuscript for the first part of The Gulag Archipelago. U.S. military attaché William Odom managed to smuggle out a large portion of Solzhenitsyn's archive, including the author's membership card for the Writers' Union and his Second World War military citations. Solzhenitsyn paid tribute to Odom's role in his memoir Invisible Allies (1995).

In West Germany, Solzhenitsyn lived in Heinrich Böll's house in Langenbroich. He then moved to Zürich, Switzerland before Stanford University invited him to stay in the United States to "facilitate your work, and to accommodate you and your family". He stayed at the Hoover Tower, part of the Hoover Institution, before moving to Cavendish, Vermont, in 1976. He was given an honorary literary degree from Harvard University in 1978 and on 8 June 1978 he gave a commencement address, condemning, among other things, the press, the lack of spirituality and traditional values, and the anthropocentrism of Western culture.[67] Solzhenitsyn also received an honorary degree from the College of the Holy Cross in 1984.

On 19 September 1974, Yuri Andropov approved a large-scale operation to discredit Solzhenitsyn and his family and cut his communications with Soviet dissidents. The plan was jointly approved by Vladimir Kryuchkov, Philipp Bobkov, and Grigorenko (heads of First, Second and Fifth KGB Directorates).[68] The residencies in Geneva, London, Paris, Rome and other European cities participated in the operation. Among other active measures, at least three StB agents became translators and secretaries of Solzhenitsyn (one of them translated the poem Prussian Nights), keeping the KGB informed regarding all contacts by Solzhenitsyn.[68]

The KGB also sponsored a series of hostile books about Solzhenitsyn, most notably a "memoir published under the name of his first wife, Natalia Reshetovskaya, but probably mostly composed by Service A", according to historian Christopher Andrew.[68] Andropov also gave an order to create "an atmosphere of distrust and suspicion between Pauk[c] and the people around him" by feeding him rumors that the people around him were KGB agents, and deceiving him at every opportunity. Among other things, he continually received envelopes with photographs of car crashes, brain surgery and other disturbing imagery. After the KGB harassment in Zürich, Solzhenitsyn settled in Cavendish, Vermont, and reduced communications with others. His influence and moral authority for the West diminished as he became increasingly isolated and critical of Western individualism. KGB and CPSU experts finally concluded that he alienated American listeners by his "reactionary views and intransigent criticism of the US way of life", so no further active measures would be required.[68]

Over the next 17 years, Solzhenitsyn worked on his dramatized history of the Russian Revolution of 1917, The Red Wheel. By 1992, four sections had been completed and he had also written several shorter works.

Solzhenitsyn's warnings about the dangers of Communist aggression and the weakening of the moral fiber of the West were generally well received in Western conservative circles (e.g. Ford administration staffers Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld advocated on Solzhenitsyn's behalf for him to speak directly to President Gerald Ford about the Soviet threat),[69] prior to and alongside the tougher foreign policy pursued by US President Ronald Reagan. At the same time, liberals and secularists became increasingly critical of what they perceived as his reactionary preference for Russian nationalism and the Russian Orthodox religion.

Solzhenitsyn also harshly criticised what he saw as the ugliness and spiritual vapidity of the dominant pop culture of the modern West, including television and much of popular music: "...the human soul longs for things higher, warmer, and purer than those offered by today's mass living habits... by TV stupor and by intolerable music." Despite his criticism of the "weakness" of the West, Solzhenitsyn always made clear that he admired the political liberty which was one of the enduring strengths of Western democratic societies. In a major speech delivered to the International Academy of Philosophy in Liechtenstein on 14 September 1993, Solzhenitsyn implored the West not to "lose sight of its own values, its historically unique stability of civic life under the rule of law—a hard-won stability which grants independence and space to every private citizen."[70]

In a series of writings, speeches, and interviews after his return to his native Russia in 1994, Solzhenitsyn spoke about his admiration for the local self-government he had witnessed first hand in Switzerland and New England.[71][72] He "praised 'the sensible and sure process of grassroots democracy, in which the local population solves most of its problems on its own, not waiting for the decisions of higher authorities.'"[73] Solzhenitsyn's patriotism was inward-looking. He called for Russia to "renounce all mad fantasies of foreign conquest and begin the peaceful long, long long period of recuperation," as he put it in a 1979 BBC interview with Latvian-born BBC journalist Janis Sapiets.[74]

In 1990, his Soviet citizenship was restored, and, in 1994, he returned to Russia with his wife, Natalia, who had become a United States citizen. Their sons stayed behind in the United States (later, his eldest son Yermolai returned to Russia). From then until his death, he lived with his wife in a dacha in Troitse-Lykovo in west Moscow between the dachas once occupied by Soviet leaders Mikhail Suslov and Konstantin Chernenko. A staunch believer in traditional Russian culture, Solzhenitsyn expressed his disillusionment with post-Soviet Russia in works such as Rebuilding Russia, and called for the establishment of a strong presidential republic balanced by vigorous institutions of local self-government. The latter would remain his major political theme.[75] Solzhenitsyn also published eight two-part short stories, a series of contemplative "miniatures" or prose poems, and a literary memoir on his years in the West The Grain Between the Millstones, translated and released as two works by the University of Notre Dame as part of the Kennan Institute's Solzhenitsyn Initiative.[76] The first, Between Two Millstones, Book 1: Sketches of Exile (1974–1978), was translated by Peter Constantine and published in October 2018, the second, Book 2: Exile in America (1978–1994) translated by Clare Kitson and Melanie Moore and published in October 2020.[77]

Once back in Russia, Solzhenitsyn hosted a television talk show program.[78] Its eventual format was Solzhenitsyn delivering a 15-minute monologue twice a month; it was discontinued in 1995.[79] Solzhenitsyn became a supporter of Vladimir Putin, who said he shared Solzhenitsyn's critical view towards the Russian Revolution.[80]

All of Solzhenitsyn's sons became U.S. citizens.[81] One, Ignat, is a pianist and conductor.[82] Another Solzhenitsyn son, Yermolai, works for the Moscow office of McKinsey & Company, a management consultancy firm, where he is a senior partner.[83]

Solzhenitsyn died of heart failure near Moscow on 3 August 2008, at the age of 89.[66][84] A burial service was held at Donskoy Monastery, Moscow, on 6 August 2008.[citation needed][85] He was buried the same day in the monastery, in a spot he had chosen.[86] Russian and world leaders paid tribute to Solzhenitsyn following his death.[citation needed][87]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Russia |

|---|

|

According to William Harrison, Solzhenitsyn was an "arch-reactionary", who argued that the Soviet State "suppressed" traditional Russian and Ukrainian culture, called for the creation of a united Slavic state encompassing Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, and who was a fierce opponent of Ukrainian independence. It is well documented that his negative views on Ukrainian independence became more radical over the years.[88] Harrison also alleged that Solzhenitsyn held Pan-Slavist and monarchist views. According to Harrison, "His historical writing is imbued with a hankering after an idealized Tsarist era when, seemingly, everything was rosy. He sought refuge in a dreamy past, where, he believed, a united Slavic state (the Russian empire) built on Orthodox foundations had provided an ideological alternative to western individualistic liberalism."[89]

Solzhenitsyn also repeatedly denounced Tsar Alexis of Russia and Patriarch Nikon of Moscow for causing the Great Schism of 1666, which Solzhenitsyn said both divided and weakened the Russian Orthodox Church at a time when unity was desperately needed. Solzhenitsyn also attacked both the Tsar and the Patriarch for using excommunication, Siberian exile, imprisonment, torture, and even burning at the stake against the Old Believers, who rejected the liturgical changes which caused the Schism.

Solzhenitsyn also argued that the Dechristianization of Russian culture, which he considered most responsible for the Bolshevik Revolution, began in 1666, became much worse during the Reign of Tsar Peter the Great, and accelerated into an epidemic during The Enlightenment, the Romantic era, and the Silver Age.

Expanding upon this theme, Solzhenitsyn once declared, "Over a half century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of old people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: 'Men have forgotten God; that's why all this has happened. Since then I have spent well-nigh 50 years working on the history of our revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous revolution that swallowed up some 60 million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: 'Men have forgotten God; that's why all this has happened.'"[90]

In an interview with Joseph Pearce, however, Solzhenitsyn commented, "[The Old Believers were] treated amazingly unjustly because some very insignificant, trifling differences in ritual which were promoted with poor judgment and without much sound basis. Because of these small differences, they were persecuted in very many cruel ways, they were suppressed, they were exiled. From the perspective of historical justice, I sympathise with them and I am on their side, but this in no way ties in with what I have just said about the fact that religion in order to keep up with mankind must adapt its forms toward modern culture. In other words, do I agree with the Old Believers that religion should freeze and not move at all? Not at all!"[91]

When asked by Pearce for his opinions about the division within the Roman Catholic Church over the Second Vatican Council and the Mass of Paul VI, Solzhenitsyn replied, "A question peculiar to the Russian Orthodox Church is, should we continue to use Old Church Slavonic, or should we start to introduce more of the contemporary Russian language into the service? I understand the fears of both those in the Orthodox and in the Catholic Church, the wariness, the hesitation, and the fear that this is lowering the Church to the modern condition, the modern surroundings. I understand this, but alas, I fear that if religion does not allow itself to change, it will be impossible to return the world to religion because the world is incapable on its own of rising as high as the old demands of religion. Religion needs to come and meet it somewhat."[92]

Surprised to hear Solzhenitsyn, "so often perceived as an arch-traditionalist, apparently coming down on the side of the reformers", Pearce then asked Solzhenitsyn what he thought of the division caused within the Anglican Communion by the decision to ordain female priests.[93]

Solzhenitsyn replied, "Certainly there are many firm boundaries that should not be changed. When I speak of some sort of correlation between the cultural norms of the present, it is really only a small part of the whole thing." Solzhenitsyn then added, "Certainly, I do not believe that women priests is the way to go!"[94]

In his 1974 essay "Repentance and Self-Limitation in the Life of Nations", Solzhenitsyn urged "Russian Gentiles" and Jews alike to take moral responsibility for the "renegades" from both communities who enthusiastically embraced atheism and Marxism–Leninism and participated in the Red Terror and many other acts of torture and mass murder following the October Revolution. Solzhenitsyn argued that both Russian Gentiles and Jews should be prepared to treat the atrocities committed by Jewish and Gentile Bolsheviks as though they were the acts of their own family members, before their consciences and before God. Solzhenitsyn said that if we deny all responsibility for the crimes of our national kin, "the very concept of a people loses all meaning."[95]

In a review of Solzhenitsyn's novel August 1914 in The New York Times on 13 November 1985, Jewish American historian Richard Pipes wrote: "Every culture has its own brand of anti-Semitism. In Solzhenitsyn's case, it's not racial. It has nothing to do with blood. He's certainly not a racist; the question is fundamentally religious and cultural. He bears some resemblance to Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who was a fervent Christian and patriot and a rabid anti-Semite. Solzhenitsyn is unquestionably in the grip of the Russian extreme right's view of the Revolution, which is that it was the doing of the Jews".[96][97] Award-winning Jewish novelist and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel disagreed and wrote that Solzhenitsyn was "too intelligent, too honest, too courageous, too great a writer" to be an anti-Semite.[98] In his 1998 book Russia in Collapse, Solzhenitsyn criticized the Russian far-right's obsession with anti-Semitic and anti-Masonic conspiracy theories.[99]

In 2001, Solzhenitsyn published a two-volume work on the history of Russian-Jewish relations (Two Hundred Years Together 2001, 2002).[100] The book triggered renewed accusations of anti-Semitism.[101][102][103][104] In the book, he repeated his call for Russian Gentiles and Jews to share responsibility for everything that happened in the Soviet Union.[105] He also downplayed the number of victims of an 1882 pogrom despite current evidence, and failed to mention the Beilis affair, a 1911 trial in Kiev where a Jew was accused of ritually murdering Christian children.[106] He was also criticized for relying on outdated scholarship, ignoring current western scholarship, and for selectively quoting to strengthen his preconceptions, such as that the Soviet Union often treated Jews better than non-Jewish Russians.[106][107] Similarities between Two Hundred Years Together and an anti-Semitic essay titled "Jews in the USSR and in the Future Russia", attributed to Solzhenitsyn, have led to the inference that he stands behind the anti-Semitic passages. Solzhenitsyn himself explained that the essay consists of manuscripts stolen from him by the KGB, and then carefully edited to appear anti-Semitic, before being published, 40 years before, without his consent.[104][108] According to the historian Semyon Reznik, textological analyses have proven Solzhenitsyn's authorship.[109]

Solzhenitsyn emphasized the significantly more oppressive character of the Soviet police state, in comparison to the Russian Empire of the House of Romanov. He asserted that Imperial Russia did not censor literature or the media to the extremely systematic style as the Soviet-era Glavlit,[110] that Tsarist era political prisoners were not forced into labor camps to even remotely the same degree,[111] and that the number of political prisoners and internal exiles under the Romanovs were only one ten-thousandth of the numbers of both following the October Revolution. He noted that the Tsar's secret police, the Okhrana, was only present in the three largest cities, and not at all in the Imperial Russian Army.[citation needed]

Shortly before his return to Russia, Solzhenitsyn delivered a speech in Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Vendée Uprising. During his speech, Solzhenitsyn compared Lenin's Bolsheviks with the Jacobin Club during the French Revolution. He also compared the Vendean rebels with the Russian, Ukrainian, and Cossack peasants who rebelled against the Bolsheviks, saying that both were destroyed mercilessly by revolutionary despotism. He commented that, while the French Reign of Terror ended with the Thermidorian reaction and the toppling of the Jacobins and the execution of Maximilien Robespierre, its Soviet equivalent continued to accelerate until the Khrushchev thaw of the 1950s.[112]

According to Solzhenitsyn, Russians were not the ruling nation in the Soviet Union. He believed that all the traditional cultures of all ethnic groups were equally oppressed in favor of atheism and Marxist–Leninism. Traditional Russian culture was even more repressed than any other culture in the Soviet Union, since the regime was more afraid of peasant uprisings by ethnic Russians than among any other Soviet ethnic group. Therefore, Solzhenitsyn argued, moderate and non-colonialist Russian nationalism and the Russian Orthodox Church, once cleansed of Caesaropapism, should not be regarded as a threat to the civilization of the West but rather as its ally.[113]

Solzhenitsyn made a speaking tour after Francisco Franco's death, and "told liberals not to push too hard for changes because Spain had more freedoms now than the Soviet Union had ever known." As reported by The New York Times, he "blamed Communism for the death of 110 million Russians and derided those in Spain who complained of dictatorship."[114] Solzhenitsyn recalled: "I had to explain to the people of Spain in the most concise possible terms what it meant to have been subjugated by an ideology as we in the Soviet Union had been, and give the Spanish to understand what a terrible fate they escaped in 1939". This was because Solzhenitsyn saw at least some parallels between the Spanish Civil War between the Nationalists and the Republicans and the Russian Civil War between the anti-communist White Army and the Communist Red Army. This was neither a popular or commonly held view at that time. Winston Lord, a protégé of the then United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, called Solzhenitsyn, "just about a fascist",[115] and Elisa Kriza alleged that Solzhenitsyn held "benevolent views" on Francoist Spain because it was a pro-Christian government, and his Christian worldview operated ideologically.[116] In The Little Grain Managed to Land Between Two Millstones, the Nationalist uprising against the Second Spanish Republic is "held up as a model of a proper Christian response", to religious persecution by the Far Left, such as the Spanish Red Terror by the Republican forces. According to Peter Brooke, however, Solzhenitsyn in reality approached the position argued by Christian Dmitri Panin, with whom he had a fall out in exile, namely that evil "must be confronted by force, and the centralised, spiritually independent Roman Catholic Church is better placed to do it than Orthodoxy with its otherworldliness and tradition of subservience to the State."[117]

In "Rebuilding Russia", an essay first published in 1990 in Komsomolskaya Pravda, Solzhenitsyn urged the Soviet Union to grant independence to all the non-Slav republics, which he claimed were sapping the Russian nation and he called for the creation of a new Slavic state bringing together Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and parts of Kazakhstan that he considered to be Russified.[118] Regarding Ukraine he wrote “All the talk of a separate Ukrainian people existing since something like the ninth century and possessing its own non-Russian language is recently invented falsehood” and "we all sprang from precious Kiev".[119][120]

In some of his later political writings, such as Rebuilding Russia (1990) and Russia in Collapse (1998), Solzhenitsyn criticized the oligarchic excesses of the new Russian democracy, while opposing any nostalgia for Soviet Communism. He defended moderate and self-critical patriotism (as opposed to extreme nationalism). He also urged for local self-government similar to what he had seen in New England town meetings and in the cantons of Switzerland. He also expressed concern for the fate of the 25 million ethnic Russians in the "near abroad" of the former Soviet Union.[citation needed]

In an interview with Joseph Pearce, Solzhenitsyn was asked whether he felt that the socioeconomic theories of E.F. Schumacher were, "the key to society rediscovering its sanity". He replied, "I do believe that it would be the key, but I don't think this will happen, because people succumb to fashion, and they suffer from inertia and it is hard to them to come round to a different point of view."[94]

Solzhenitsyn refused to accept Russia's highest honor, the Order of St. Andrew, in 1998. Solzhenitsyn later said: "In 1998, it was the country's low point, with people in misery; ... Yeltsin decreed I be honored the highest state order. I replied that I was unable to receive an award from a government that had led Russia into such dire straits."[121] In a 2003 interview with Joseph Pearce, Solzhenitsyn said: "We are exiting from communism in a most unfortunate and awkward way. It would have been difficult to design a path out of communism worse than the one that has been followed."[122]

In a 2007 interview with Der Spiegel, Solzhenitsyn expressed disappointment that the "conflation of 'Soviet' and 'Russian'", against which he spoke so often in the 1970s, had not passed away in the West, in the ex-socialist countries, or in the former Soviet republics. He commented, "The elder political generation in communist countries is not ready for repentance, while the new generation is only too happy to voice grievances and level accusations, with present-day Moscow [as] a convenient target. They behave as if they heroically liberated themselves and lead a new life now, while Moscow has remained communist. Nevertheless, I dare [to] hope that this unhealthy phase will soon be over, that all the peoples who have lived through communism will understand that communism is to blame for the bitter pages of their history."[121]

In 2008, Solzhenitsyn praised Putin, saying Russia was rediscovering what it meant to be Russian. Solzhenitsyn also praised the Russian president Dmitry Medvedev as a "nice young man" who was capable of taking on the challenges Russia was facing.[123]

Once in the United States, Solzhenitsyn sharply criticized the West.[124]

Solzhenitsyn criticized the Allies for not opening a new front against Nazi Germany in the west earlier in World War II. This resulted in Soviet domination and control of the nations of Eastern Europe. Solzhenitsyn claimed the Western democracies apparently cared little about how many died in the East, as long as they could end the war quickly and painlessly for themselves in the West.[citation needed]

Delivering the commencement address at Harvard University in 1978, he argued that the United States had declined in terms of its "spiritual life" and called for a "spiritual upsurge". He added "should someone ask me whether I would indicate the West such as it is today as a model to my country, frankly I would have to answer negatively". He critiqued the West for its lack of religiosity, materialism, and a "decline in courage".[125]

Solzhenitsyn was a supporter of the Vietnam War and referred to the Paris Peace Accords as 'shortsighted' and a 'hasty capitulation'.[126]

In a reference to the Communist governments in Southeast Asia's use of re-education camps, politicide, human rights abuses, and genocide following the Fall of Saigon, Solzhenitsyn said: "But members of the U.S. antiwar movement wound up being involved in the betrayal of Far Eastern nations, in a genocide and in the suffering today imposed on 30 million people there. Do those convinced pacifists hear the moans coming from there?"[127]

He also accused the Western news media of left-wing bias, of violating the privacy of celebrities, and of filling up the "immortal souls" of their readers with celebrity gossip and other "vain talk". He also said that the West erred in thinking that the whole world should embrace this as model. While faulting Soviet society for rejecting basic human rights and the rule of law, he also critiqued the West for being too legalistic: "A society which is based on the letter of the law and never reaches any higher is taking very scarce advantage of the high level of human possibilities." Solzhenitsyn also argued that the West erred in "denying [Russian culture's] autonomous character and therefore never understood it".[67]

Solzhenitsyn criticized the 2003 invasion of Iraq and accused the United States of the "occupation" of Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq.[128]

Solzhenitsyn was critical of NATO's eastward expansion towards Russia's borders.[129] In 2006, Solzhenitsyn accused NATO of trying to bring Russia under its control; he claimed this was visible because of its "ideological support for the 'colour revolutions' and the paradoxical forcing of North Atlantic interests on Central Asia".[129] In a 2006 interview with Der Spiegel he stated "This was especially painful in the case of Ukraine, a country whose closeness to Russia is defined by literally millions of family ties among our peoples, relatives living on different sides of the national border. At one fell stroke, these families could be torn apart by a new dividing line, the border of a military bloc."[121]

Solzhenitsyn gave a speech to AFL–CIO in Washington, D.C., on 30 June 1975 in which he said that the system created by the Bolsheviks in 1917 caused dozens of problems in the Soviet Union.[130] He described how this system was responsible for the Holodomor: "It was a system which, in time of peace, artificially created a famine, causing 6 million people to die in the Ukraine in 1932 and 1933." Solzhenitsyn added, "they died on the very edge of Europe. And Europe didn't even notice it. The world didn't even notice it—6 million people!"[130]

Shortly before his death, Solzhenitsyn opined in an interview published 2 April 2008 in Izvestia that, while the famine in Ukraine was both artificial and caused by the state, it was no different from the Russian famine of 1921–1922. Solzhenitsyn expressed the belief that both famines were caused by systematic armed robbery of the harvests from both Russian and Ukrainian peasants by Bolshevik units, which were under orders from the Politburo to bring back food for the starving urban population centers while refusing for ideological reasons to permit any private sale of food supplies in the cities or to give any payment to the peasants in return for the food that was seized.[131] Solzhenitsyn further alleged that the theory that the Holodomor was a genocide which only victimized the Ukrainian people was created decades later by believers in an anti-Russian form of extreme Ukrainian nationalism. Solzhenitsyn also cautioned that the ultranationalists' claims risked being accepted without question in the West due to widespread ignorance and misunderstanding there of both Russian and Ukrainian history.[131]

The Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn Center in Worcester, Massachusetts promotes the author and hosts the official English-language website dedicated to him.[132]

In October 1983, French literary journalist Bernard Pivot made an hour-long television interview with Solzhenitsyn at his rural home in Vermont, US. Solzhenitsyn discussed his writing, the evolution of his language and style, his family and his outlook on the future—and stated his wish to return to Russia in his lifetime, not just to see his books eventually printed there.[133][134] Earlier the same year, Solzhenitsyn was interviewed on separate occasions by two British journalists, Bernard Levin and Malcolm Muggeridge.[133]

In 1998, Russian filmmaker Alexander Sokurov made a four-part television documentary, Besedy s Solzhenitsynym (The Dialogues with Solzhenitsyn). The documentary was shot in Solzhenitsyn's home depicting his everyday life and his reflections on Russian history and literature.[135]

In December 2009, the Russian channel Rossiya K broadcast the French television documentary L'Histoire Secrète de l'Archipel du Goulag (The Secret History of the Gulag Archipelago)[136] made by Jean Crépu and Nicolas Miletitch[137] and translated into Russian under the title Taynaya Istoriya "Arkhipelaga Gulag" (Тайная история "Архипелага ГУЛАГ"). The documentary covers events related to the creation and publication of The Gulag Archipelago.[136][138][139]

|

Main article: Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn bibliography |

((citation)): CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link).[140]