| Cotentinais | |

|---|---|

Map of Cotentin peninsula | |

| Region | Cotentin Peninsula |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | nrf |

Cotentinais (French pronunciation: [kɔtɑ̃tinɛ]) is the dialect of the Norman language spoken in the Cotentin Peninsula of France. It is one of the strongest dialects of the language on the French mainland.

Due to the relative lack of standardisation of Norman, there are five main subdialects of Cotentinais:

At the end of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th century a new movement arose in the Channel Islands, led by writers such as George Métivier (Guernsey, 1790–1881—dubbed the Guernsey Burns) and writers from Jersey. The independent governments, lack of censorship and diverse social and political milieu of the Islands enabled a growth in the publication of vernacular literature—often satirical and political.

Most literature was published in the large number of competing newspapers, which also circulated in the neighbouring Cotentin, sparking a literary renaissance on the Norman mainland.

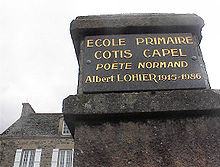

The Norman poet Côtis-Capel (1915–1986) was a native of the Cotentin and used the landscape as inspiration for his poetry.

The Norman language writer Alfred Rossel, native of Cherbourg, composed many songs which form part of the heritage of the region. Rossel's song Sus la mé ("on the sea") is often sung as a regional patriotic song.

Each sub-group has some characteristics which made it possible to define them:

The dialect of La Hague is very guttural, in particular by the hard pronunciation of Norman aspirated H ("Hague" is typically pronounced [hrague] in the region). It pronounces the verbs of the first group with final in [ - has ]: chauntaer (to sing) is read [chanhanta] /ʃaɔ̃tɑ/. It is the same for the conjugation with the last participle. Exception, in the two communes of Cap de La Hague (Auderville and Saint-Germain-des-Vaux) where one pronounces [chanhanto] /ʃaɔ̃to/.

The dialect of the Val de Saire, pronounces in the same way finals of the verbs of the first group in [-o]: acataer (to buy) is read [acato]. With the past participle, even pronunciation, except with the female one: [acata:] with one [-a:] length. Example: Ole a 'taé acataée sauns câotioun will say [ôlata: acata: sahan kâossiahon] = (it was bought without guarantee)

The dialects of north and south Coutançais pronounce the verbs of the first group and their participle past in [-âé] or [-âè]: happaer (to catch) is thus said [hrapâé]. Caught will result in happaée [hrappaée]. The difference between these two group resides more on the pronunciation of [qŭ-] Norman. Here, for qŭyin (dog), one will say [ki'i], [tchi], or [tchihin] (with one [-hin] final hardly audible). for comparison, let us recall that in Cauchois, one says [ki'in].

The Baupteis, the dialect of Bauptois, are close to the languages of Coutançais for the verbs to first group and it [qŭ-]. On the other hand, it has the characteristic to pronounce it [âo] cotentinais in [è], which does not facilitate comprehension of it. This provision did not appear besides in the dialectal literature and thus almost disappeared. Where everywhere in Normandy one says câosaer (to discuss), marked [kâoza, kâozo, kâozaé, kâozaè, or kâozé] according to preceding sub-groups' and as a Norman Southerner [kâozé], the language of Bauptois will say [kèzaé] or [kèzâè] or rarely [kèza]. Thus the câode iâo (hot water) will say it [kèdiè]. Bâopteis decides there besides [bèté:].

Each sub-group thus also has its Norman language authors who, even if they have used or contributed to the development of a coherent and unified orthography, have written texts specific to each sub-group, but readable by all. Thus, the rich vocabulary of Cotentinais was turned to literary purpose by several poets and writers at the 19th and 20th centuries, in particular:

Alfred Rossel, precursor of the writing into Norman of Cotentin writes Norman "area of Cherbourg", i.e. between this city and Valognes, which can be connected to the sub-groups of La Hague, the Valley of Saire and Bauptois.

Cotentinais is still spoken today, but sparsely, and cultural activity is maintained by some folk associations (songs, dances, magazines) and especially by the Magène association which aims to safeguard and to promote Norman by publishing of discs and books.