| HU-16 Albatross | |

|---|---|

| |

| A U.S. Navy Grumman UF-1 Albatross | |

| Role | Air-sea rescue flying boat |

| Manufacturer | Grumman |

| First flight | October 24, 1947[1] |

| Introduction | 1949 |

| Retired | 1995 (Hellenic Navy) |

| Status | In limited use |

| Primary users | United States Air Force United States Coast Guard United States Navy Royal Canadian Air Force Hellenic Navy |

| Produced | 1949–1961 |

| Number built | 466 |

| Developed from | Grumman Mallard |

The Grumman HU-16 Albatross is a large, twin–radial engined amphibious seaplane that was used by the United States Air Force (USAF), the U.S. Navy (USN), the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG), and the Royal Canadian Air Force primarily as a search and rescue (SAR) aircraft. Originally designated as the SA-16 for the USAF and the JR2F-1 and UF-1 for the USN and USCG, it was redesignated as the HU-16 in 1962. A new build G-111T Albatross with modern avionics and engines was proposed in 2021 with production in Australia to commence in 2025.[2]

Design and development

[edit]An improvement of the design of the Grumman Mallard, the Albatross was developed to land in open-ocean situations to accomplish rescues. Its deep-V hull cross-section and keel length enable it to land in the open sea. The Albatross was designed for optimal 4-foot (1.2 m) seas, and could land in more severe conditions, but required JATO (jet-assisted takeoff, or simply booster rockets) for takeoff in 8–10-foot (2.4–3.0 m) seas or greater.

Operational history

[edit]

Most Albatrosses were used by the U.S. Air Force (USAF), primarily in the search and rescue (SAR) mission role, and initially designated as SA-16. The USAF used the SA-16 extensively in Korea for combat rescue, where it gained a reputation as a rugged and seaworthy craft. Later, the redesignated HU-16B (long-wing variant) Albatross was used by the USAF's Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service and saw extensive combat service during the Vietnam War. In addition, a small number of Air National Guard air commando groups were equipped with HU-16s for covert infiltration and extraction of special forces from 1956 to 1971.[3] Other examples of the HU-16 made their way into Air Force Reserve rescue and recovery units prior to its retirement from USAF service.

The U.S. Navy also employed the HU-16C/D Albatross as an SAR aircraft from coastal naval air stations, both stateside and overseas. It was also employed as an operational support aircraft worldwide and for missions from the former Naval Air Station Agana, Guam, during the Vietnam War. Goodwill flights were also common to the surrounding Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands in the early 1970s. Open-water landings and water takeoff training using JATO was also conducted frequently by U.S. Navy HU-16s from locations such as NAS Agana, Guam; Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; NAS Barbers Point, Hawaii; NAS North Island, California, NAS Key West, Florida; NAS Jacksonville, Florida, and NAS Pensacola, Florida, among other locations.

The HU-16 was also operated by the U.S. Coast Guard as both a coastal and long-range open-ocean SAR aircraft for many years until it was supplanted by the HU-25 Guardian and HC-130 Hercules.

The final USAF HU-16 flight was the delivery of AF Serial No. 51-5282 to the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, in July 1973 after setting an altitude record of 32,883 ft earlier in the month.[4]

The final US Navy HU-16 flight was made 13 August 1976, when an Albatross was delivered to the National Museum of Naval Aviation at NAS Pensacola, Florida.[5]

The final USCG HU-16 flight was at CGAS Cape Cod in March 1983, when the aircraft type was retired by the USCG. The Albatross continued to be used in the military service of other countries, the last being retired by the Hellenic Navy (Greece) in 1995.

The Pakistan Air Force operated 4 SA-16As from 1958 to 1968 which it received under the MAP program. It's No. 4 Squadron was equipped with these hydroplanes while based at Drigh Road Air Base. The SA-16s were used for maritime reconnaissance and coastal patrol during the 1965 War with India. At least one SA-16 was on patrol during the 17 day war flying 14 missions in support of the Navy. They were put in storage on 19 August 1968.[6][7]

The Royal Canadian Air Force operated Grumman Albatrosses with the designation "CSR-110".

Civil operations

[edit]

In the mid-1960s the U.S. Department of the Interior acquired three military Grumman HU-16s from the U.S. Navy and established the Trust Territory Airlines in the Pacific to serve the islands of Micronesia. Pan American World Airways and finally Continental Airlines' Air Micronesia operated the Albatrosses serving Yap, Palau, Chuuk (Truk), and Pohnpei from Guam until 1970, when adequate island runways were built, allowing land operations.

Many surplus Albatrosses were sold to civilian operators, mostly to private owners. These aircraft are operated under either Experimental-Exhibition or Restricted category and cannot be used for commercial operations, except under very limited conditions.

In the early 1980s, Chalk's International Airlines owned by Merv Griffin's Resorts International had 13 Albatrosses converted to Standard category as G-111s. This made them eligible to be used in scheduled airline operations. These aircraft had extensive modification from the standard military configuration, including rebuilt wings with titanium wing spar caps, additional doors and modifications to existing doors and hatches, stainless steel engine oil tanks, dual engine fire extinguishing systems on each engine, and propeller auto feather systems installed. The G-111s were operated for only a few years and then put in storage in Arizona. Most are still parked there, but some have been returned to regular flight operations with private operators.

Satellite technology company Row 44, now known as Anuvu, bought an HU-16B Albatross (registration N44HQ)[8] in 2008 to test its in-flight satellite broadband internet service. Named Albatross One, the company selected the aircraft for its operations because it has the same curvature atop its fuselage as the Boeing 737 aircraft for which the company manufactures its equipment. The plane purchased by Row 44 was used at one time as a training aircraft for space shuttle astronauts by NASA. It features the autographs of the astronauts who trained aboard the plane on one of the cabin walls.[9][10]

In 1997, a Grumman Albatross (N44RD), piloted by Reid Dennis and Andy Macfie, became the first Albatross to circumnavigate the globe. The 26,347 nmi flight around the world lasted 73 days, included 38 stops in 21 countries, and was completed with 190 hours of flight time.[11] In 2013 Reid Dennis donated N44RD to the Hiller Aviation Museum.[12]

Since the aircraft weighs over 12,500 pounds, pilots of civilian US-registered Albatross aircraft must have a type rating. A yearly Albatross fly-in is held at Boulder City, Nevada, where Albatross pilots can become type rated.

Proposed new build

[edit]Amphibian Aerospace Industries in Darwin, Australia, acquired the type certificate and announced in December 2021 that it planned to commence manufacturing a new version of the Albatross from 2025. Dubbed the G-111T, it would have modern avionics and Pratt & Whitney PT6A-67F turboprop engines, with variants for passengers, freight, search and rescue, coastal surveillance, and aeromedical evacuation.[13][14]

Variants

[edit]

- XJR2F-1 - Prototype designation, two built

- HU-16A (originally SA-16A) - USAF version

- HU-16A (originally UF-1) - Indonesian version

- HU-16B (originally SA-16B) - USAF version (modified with long wing)

- SHU-16B (modified HU-16B for Anti-Submarine Warfare) - export version, featured an AN/APS-88 in the nose and MAD boom in the tail[15]

- HU-16C (originally UF-1) - US Navy version

- LU-16C (originally UF-1L) - US Navy version

- TU-16C (originally UF-1T) - US Navy version

- HU-16D (originally UF-1) - US Navy version (modified with long wing)

- HU-16D (originally UF-2) - German version (built with long wing)

- HU-16E (originally UF-2G) - US Coast Guard version (modified with long wing)

- HU-16E (originally SA-16A) - USAF version (modified with long wing)

- G-111 (originally SA-16A) - civil airline version derived from USAF, JASDF, and German originals

- CSR-110 - RCAF version[16]

- G-111T - proposed new builds with modern avionics and turboprop engines.

Operators

[edit] Argentina

Argentina

- Argentine Air Force - 3 aircraft.[17]

- Argentine Naval Aviation - 4 aircraft.[18]

Brazil

Brazil

Canada

Canada

Chile

Chile

Republic of China

Republic of China

Germany

Germany

Greece

Greece

Indonesia

Indonesia

- Indonesian Navy[26]

- Indonesian Air Force[27]

- Airfast Indonesia[28]

- Dirgantara Air Service[29]

- Pelita Air[29]

Italy

Italy

Japan

Japan

Malaysia

Malaysia

Mexico

Mexico

Norway

Norway

Pakistan

Pakistan

Peru

Peru

Philippines

Philippines

Portugal

Portugal

Spain

Spain

Thailand

Thailand

United States

United States

Aircraft on display

[edit]- HU-16A

- AF Ser. No. 51-0006 - Strategic Air and Space Museum in Ashland, Nebraska[42]

- AF Ser. No. 51-0022 - Pima Air and Space Museum adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson, Arizona[43]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7144 - Museum of Aviation, Robins AFB, Georgia[44]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7163 - Castle Air Museum adjacent to the former Castle AFB, Atwater, California[45]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7176 - Coast Guard Air Station Clearwater, Florida: It was previously at the Pate Museum of Transportation in Cresson, Texas, until its disassembly and relocation to CGAS Clearwater for restoration. It is currently marked as USCG 1023.[46]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7193 - Maryland Air National Guard Museum, Warfield Air National Guard Base, Baltimore, Maryland[47]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7195 - Yanks Air Museum, Chino, California[48]

- MM50-179 - Italian Air Force Museum, Vigna di Valle, Italy [49]

- 48607 - Philippine Air Force Aerospace Museum, Pasay City, Philippines

- HU-16A (Indonesian version)

- IR-0117 – On display at Dirgantara Mandala Museum, Sleman Regency, Special Region of Yogyakarta, Indonesia[50]

- IR-0220 – On storage in Husein Sastranegara International Airport, Bandung, West Java, Indonesia: It was displayed during Bandung Airshow 2017.[51][52]

- Unknown – On display at Abdul Rachman Saleh Air Force Base, Malang, East Java, Indonesia.[53]

- HU-16B

- BS-02 - Museo Nacional de Aeronáutica de Argentina, at Moron, Buenos Aires, Argentina[54][55]

- ex-BS-03 - Museo Aviación Naval, Buenos Aires, Argentina. Displayed as Argentine Naval Aviation 4-BS-3.[18]

- AF Serial No. 51-5282, at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio: This was USAF's last operational HU-16. On 4 July 1973, it established a world record for twin-engined amphibians when it reached 32,883 feet and was transferred to the Air Force Museum two weeks later.[56]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7181, then BuNo 151265 - U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield, Sattahip, Chonburi Province, Thailand[57][58] Former USAF and USN aircraft in Royal Thai Navy markings, now bearing registration 151265 and displayed as a gate guardian since the early 1990s.

- HU-16C

- BuNo 137928 Hemisphere Dancer - Universal Studios, Orlando, Florida[59] Former USN aircraft in civilian markings, previously owned by musician and pilot Jimmy Buffett

- BuNo 137932 - Hiller Aviation Museum, San Carlos, California, N44RD formerly owned by Reid W. Dennis.[60]

- HU-16E

- AF Ser. No. 51-7209 - Aerospace Museum of California, former McClellan AFB, Sacramento, California[61]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7216 - Floyd Bennett Field, New York City, New York[62]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7228 - New England Air Museum, Windsor Locks, Connecticut[63]

- USCG 7236 - National Museum of Naval Aviation, NAS Pensacola, Florida[64]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7245, then USCG 7245 - Pacific Coast Air Museum, Santa Rosa, California[65] Originally served in USAF, transferred to USCG circa 1957-58.

- AF Ser. No. 51-7247, then USCG 7247 - Coast Guard Air Station Elizabeth City, North Carolina.[66]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7250, the USCG 7250 - Coast Guard Air Station Cape Cod, Massachusetts[67]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7251 - Dyess Linear Air Park, Dyess AFB, Texas[68]

- AF Ser. No. 51-7254 - Jimmy Doolittle Air & Space Museum, Travis AFB, Fairfield, California[69]

- AF Ser. No. 52-1280 - Kirtland AFB, Albuquerque, New Mexico.[70]

- USCG 1293 - March Field Air Museum, March ARB, Riverside, California.[71]

- USCG 2129 - Battleship Memorial Park, Mobile, Alabama[72]

One UF-1G is operated by TP Universal Exports in Minnesota and is still flying today.

Accidents and incidents

[edit]- On 24 January 1952, SA-16A Albatross, 51-001, c/n G-74,[73] of the 480th Air Resupply Squadron (described as a Central Intelligence Agency air unit), on cross-country flight from Mountain Home AFB, Idaho, to San Diego, California, suffered failure of the port engine over Death Valley. The crew of six successfully bailed out around 18:30 with no injuries, and walked south some 14 miles (23 km) to Furnace Creek, California, where they were picked up the following day by an SA-16 from the 42nd Air Rescue Squadron, March AFB, California. The abandoned SA-16 crashed into Towne Summit mountain ridge of the Panamint Range west of Stovepipe Wells with the starboard engine still running. The wreckage is still there.[74][75]

- On 16 May 1952, a U.S. Navy Grumman Albatross attached to the Iceland Defense Force crashed on Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland. Due to bad weather conditions, rescuers did not make it to the crash site until two and a half days later. One crew member was found dead in the wreckage, but the other four were not found despite extensive search. Evidence on scene suggested that they had tried to deploy the emergency radio, but most likely failed due to very poor weather conditions, and then tried to walk down the glacier.[76] In 1964, partial remains of one of the crewmember along with an engraved wedding ring were found at the rim of the glacier.[77] On 20 August 1966, the remains of the three remaining crew members were found at a similar location.[78][79]

- On 18 May 1957, U.S. Coast Guard HU-16E Albatross, Coast Guard 1278, stalled and crashed during a JATO demonstration during the Armed Forces Day display at Coast Guard Air Station Salem. The pilot and another crewman were killed. The stall was caused by pilot error.[80]

- On 22 August 1957, U.S. Coast Guard HU-16E Albatross, Coast Guard 1259, crashed during takeoff at Floyd Bennett Field, killing 4 of the 6 crew on board. The aircraft had just completed an inspection in which the control columns were removed and inspected for fatigue cracks. Although not proven, it is believed that poor maintenance during the re-installation of the control columns led to the crash.[81]

- On 3 July 1964, U.S. Coast Guard HU-16E Albatross, Coast Guard 7233, was lost along with all five crew members as it returned from a search for a missing fishing boat. Two days later, the wreckage was found on a mountainside, 3 miles (4.8 km) from its base at Air Station Annette, Alaska.[82]

- On 18 June 1965, on the first Operation Arc Light mission flown by B-52 Stratofortresses of Strategic Air Command to hit a target in South Vietnam, two aircraft collided in the darkness. Eight crew were killed, but four survivors were located and picked up by an HU-16A-GR Albatross amphibian, AF serial number 51-5287. The Albatross was damaged on take-off by a heavy sea state, and those on board had to transfer to a Norwegian freighter and a Navy vessel, the aircraft sinking thereafter.[83]

- On 9 January 1966, a Republic of China Air Force HU-16 carrying three mainland Chinese naval defectors, two officers of the Defense Ministry and four officers of the Matsu Defense Command,[84] was shot down by communist MiGs over the Taiwan Straits, just hours after they had surrendered their landing ship and asked for asylum. The Albatross was attacked just 15 minutes after departing the island of Matsu on a 135 miles (217 km) flight to Taipei. According to a U.S. Defense Department announcement, the attack was a swift—and perhaps intentional—retribution for the communist sailors who killed seven fellow crew members during their predawn escape to freedom.[85]

- On 23 April 1966, a Royal Canadian Air Force Grumman CSR-110 Albatross (9302) serving with No. 121 Composite Unit (KU) at RCAF Station Comox, BC crashed on the Hope Slide near Hope, BC. It was the only RCAF Albatross loss. Five of the six crew members died (Squadron Leader J. Braiden, Flying Officer Christopher J. Cormier, Leading Aircraftsman Robert L. McNaughton, Flight Lieutenant Phillip L. Montgomery, and Flight Lieutenant Peter Semak). Flying Officer Bob Reid was the sole survivor. A portion of the wreckage is still visible and can be hiked to.

- On 18 January 1967, a Grumman HU-16A Albatross operated by the Air Force of the Republic of Indonesia (AURI), military registration 302, en route to Malang-Abdul Rachman Saleh Airport (MLG/WARA), was reported as missing with the loss of all 19 occupants onboard.[86][87]

- On 5 March 1967, U.S. Coast Guard HU-16E Albatross, Coast Guard 1240, c/n G-61, out of Coast Guard Air Station St. Petersburg, Florida, deployed to drop a dewatering pump to a sinking 40-foot (12 m) yacht, Flying Fish, in the Gulf of Mexico off of Carrabelle, Florida. Shortly after making a low pass behind the sinking vessel to drop the pump, the flying boat crashed a short distance away, with loss of all six crew. The vessel's crew heard a loud crash, but could see nothing owing to fog. The submerged wreck was not identified until 2006.[88][89]

- On 15 June 1967, U.S. Coast Guard HU-16E Albatross, Coast Guard 7237, was based at Coast Guard Air Station Annette Island, in Alaska. The crew was searching near Sloko Lake, British Columbia, Canada, for a missing light plane. The pilot began following the river up to Sloko Lake, intending to turn around at the lake and fly back out of the valley. The co-pilot called for a right turn, but for some reason, the plane went left. According to reports, the co-pilot shouted, “Come right! Come right!” The plane hit the mountain, and burst into flames. The three observers in the back were able to get clear of the wreckage, and reported seeing an intense fire engulf the front half of the aircraft. Pilot Lt. Robert Brown, co-pilot Lt. David Bain, and radio operator AT2 Robert Striff, Jr., however, were killed. The wreckage can still be seen on the side of the mountain in Atlin Provincial Park.[90]

- On 7 August 1967, U.S. Coast Guard HU-16E Albatross, Coast Guard 2128, c/n G-355, (ex-USAF SA-16A, 52-128), out of CGAS San Francisco, returning from a search mission for an overdue private cabin cruiser Misty (which had run out of fuel) in the Pacific Ocean off of San Luis Obispo, struck a slope of Mount Mars near the Monterey-San Luis Obispo County line, about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) east of Highway 1. The airframe broke in two, killing two crew immediately and injuring four others, with one dying in the hospital several days later.[91]

- On 21 September 1973, U.S. Coast Guard HU-16E Albatross, Coast Guard 2123, was lost over the Gulf of Mexico. The crew was dropping flares over a search area when one flare ignited inside the aircraft, incapacitating the pilots, which led the aircraft to enter an uncontrollable spin. All seven on board were killed.[82]

- On 23 January 1986, Indonesian Air Force HU-16A Albatross number IR-0222 crashed into the water at Makassar harbor during an attempted emergency landing. Five out of 8 crew were killed in the accident. The wreckage also blocked the harbor and delaying a Pelni liner from docking.[92]

- On 5 November 2009, Albatross N120FB of Albatross Adventures crashed shortly after take-off from St. Lucie County International Airport, Fort Pierce, Florida. An engine failed shortly after take-off; the aircraft was damaged beyond economic repair.[93]

Specifications (HU-16B)

[edit]Data from Albatross: Amphibious Airborne Angel,[94] United States Navy Aircraft since 1911,[95] Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1958-59[96] Grumman Albatross: A History of the Legendary Seaplane[97]

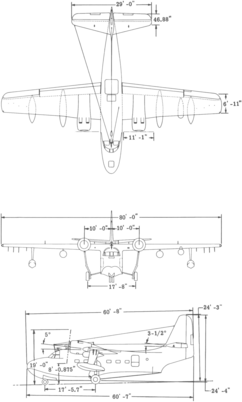

General characteristics

- Crew: 4-6

- Capacity: 10 passengers

- Length: 62 ft 10 in (19.15 m)

- Wingspan: 96 ft 8 in (29.46 m)

- Height: 25 ft 10 in (7.87 m)

- Wing area: 1,035 sq ft (96.2 m2)

- Airfoil: NACA 23017[98]

- Empty weight: 22,883 lb (10,380 kg)

- Gross weight: 30,353 lb (13,768 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 37,500 lb (17,010 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 675 US gal (562.1 imp gal; 2,555.2 L) internal fuel + 400 US gal (333.1 imp gal; 1,514.2 L) in wingtip floats + two 300 US gal (249.8 imp gal; 1,135.6 L) drop tanks

- Powerplant: 2 × Wright R-1820-76A Cyclone 9 9-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engines, 1,425 hp (1,063 kW) each for take-off

- 1,275 hp (951 kW) normal rating from sea level to 3,000 ft (914 m)

- Propellers: 3-bladed Hamilton Standard constant-speed fully-feathering reversible-pitch propellers

Performance

- Maximum speed: 236 mph (380 km/h, 205 kn)

- Cruise speed: 124 mph (200 km/h, 108 kn)

- Stall speed: 74 mph (119 km/h, 64 kn)

- Range: 2,850 mi (4,590 km, 2,480 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 21,500 ft (6,600 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,450 ft/min (7.4 m/s)

Avionics

- AN/APS-31A search radar

See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

References

[edit]- ^ Pigott, Peter (2001). Wings across Canada: an illustrated history of Canadian aviation. Dundurn Press. p. 121. ISBN 1-55002-412-4.

- ^ "Australia to restart HU-16 production after 60 years". 14 December 2021.

- ^ Minami, Wayde. "Albatross Was a Maryland Air Guard Classic". 175th Wing, Air National Guard. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22.

- ^ "Grumman HU-16B Albatross". National Museum of the United States Air Force. May 29, 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Grossnick, Roy A. "Part 10: The Seventies 1970–1980" (PDF). United States Naval Aviation 1910–1995. Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center Department of the Navy. pp. 279–330.

- ^ Fricker, John (1979). Battle for Pakistan. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 0711009295.

- ^ Hussain, Shabbbir; Quraishi, Tariq (1982). History of the Pakistan Air Force, 1947-1982. p. 57.

- ^ "FAA Aircraft Registry N44HQ". Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Albatross One". row44.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Speedy In-Flight Wi-Fi, Even During a Wild Ride". The New York Times. 17 October 2011. Archived from the original on 14 December 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Foreman, Herb (March 11, 2013). "Record Holding Albatross Retires to Hiller Aviation Museum". In Flight USA. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ^ Murtagh, Heather (April 29, 2013). "Hiller gets amphibious contribution". San Mateo Daily News. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ^ "Albatross flying boat returns and will be built in NT". Australian Aviation. 13 December 2021.

- ^ "Albatross 2.0". Amphibian Aerospace Industries.

- ^ Mutza, Wayne (1996). Grumman Albatross: A History of the Legendary Seaplane. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 0-88740-913-X.

- ^ Wolfe, Ray. "Albatross Current Status List". Grumman Albatross Research. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- ^ "ARGENTINA'S REORGANISED AIR ARM pg. 385". flightglobal.com. 1969. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ a b Núñez Padin, Jorge Felix (2009).

- ^ "World Air Forces 1971 pg. 924". Flightglobal Insight. 1971. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Aircraft – ITPS Canada". Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- ^ Canadian Warbirds of the Post-War Piston Era. Writers Press Club. 2001. ISBN 9780595184200. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1971 pg. 926". Flightglobal Insight. 1971. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 92". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1971 pg. 928". Flightglobal Insight. 1971. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 59". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1971 pg. 930". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ TNI, PUSPEN TNI, Puspen Mabes. "LINTASAN SEJARAH ANGKATAN UDARA | WEBSITE TENTARA NASIONAL INDONESIA". tni.mil.id. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

((cite web)): CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "SOUTH EAST ASIA 1960s-1970s - INDONESIA & DUTCH NEW GUINEA". goodall.com.au. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b "SINGAPORE-SELETAR AIRPORT 1981". goodall.com.au. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d "GRUMMAN SA-16 / UF ALBATROSS". uswarplanes.net. 2018. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 68". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 72". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1971 pg. 934". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "PAKISTAN'S AIR POWER pg. 92". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1971 pg. 935". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1987 pg. 78". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Altimagem: Grumman SA-16 Albatross".

- ^ "World Air Forces 1971 pg. 937". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "World Air Forces 1955 pg. 664". flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Historian's Office". history.uscg.mil. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "HU-16E Albatross". marchfield.org. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-0006". Strategic Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on 24 October 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-0022". Pima Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7144". Museum of Aviation. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7163". Castle Air Museum. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7176". Pier System. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7193". Aero Web. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7195". Yanks Air Museum. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16A Albatross/MM50-179". Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ "The Grumman Albatross Web Site – Albatrosses in Museum". hu-16.com. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Bandung Air Show 2017 Akan Hadir di Bandara Husein Sastranegara". jabar.inews.id (in Indonesian). 8 November 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "The Sea Scouts". fenomenanews.com (in Indonesian). 21 December 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Lanud Abd Saleh Geser Pesawat Albatros ke Jogging Track". tni-au.mil.id (in Indonesian). 6 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Esteban Brea (2012-03-13). "Museo Nacional de Aeronáutica: Más de medio siglo de preservación" [National Aeronautics Museum: More than half a century of preservation] (in Spanish). Gaceta Aeronautica. Archived from the original on 9 December 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ Cater & Caballero (IPMS Magazine May 2013)

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-5282". National Museum of the US Air Force. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ https://www.goodall.com.au/grumman-amphibians/grummanalbatross.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Aviation Photo #1838634: Grumman HU-16B Albatross - Thailand - Navy".

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/137928". Buffett World. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ Highton, Scott. "Virtual Reality Tour Grumman Albatross HU-16C". Hiller Aviation Museum. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7209". Aerospace Museum of California. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7216". Aero Web. Archived from the original on 30 May 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7228". New England Aviation Museum. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7236". National Museum of Naval Aviation. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7245". Pacific Coast Air Museum. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7247". Warbirds Resource Group. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7250". HU-16 Museums. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7251". Aero Web. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/51-7254". Jimmy Doolittle Museum. 9 September 2012. Archived from the original on 27 August 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/1280". Aero Web. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/1293". March Field Air Museum. Archived from the original on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "HU-16 Albatross/2129". USS Alabama Museum. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "1951 USAF Serial Numbers". Joebaugher.com. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ "Albatross Plane Crash Site". Death-Valley.net. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ "Video of wreck site". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Ameríska björgunarflugvélin fannst uppi á Eyjafjallajökli í gær". Alþýðublaðið (in Icelandic). 20 May 1952. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ "Fundu leifar af mannslíkama á Eyjafjallajökli". Alþýðublaðið (in Icelandic). 26 May 1964. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ "Þrjú lík bandarískra flugmanna fundust uppi á Eyjafjallajökli". Tíminn (in Icelandic). 22 August 1966. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ "Lík bandarískra flugmanna finnast á Eyjafjallajökli". Þjóðviljinn (in Icelandic). 22 August 1966. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ "Armed Forces Day Crash".

- ^ "Four Perish in USCG Test Flight".

- ^ a b "Fatal Coast Guard Aircraft Accidents".

- ^ Schlight, John (1988). The War in South Vietnam: The Years of the Offensive, 1965-1968 (The United States Air Force in Southeast Asia). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force. p. 52. ISBN 0-912799-51-X.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Grumman HU-16A Albatross 11021 Taiwan Strait". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ "Migs [sic] Shoot Down Unarmed Chinese Plane". Playground Daily News. Vol. 19, no. 342. Fort Walton Beach, FL. United Press International. 10 January 1966. p. 2.

- ^ "The Straits Times". 21 January 1967. p. 1.

- ^ "ASN aircraft accident Grumman HU-16A Albatross 302 Java". Aviation-Safety.net. Flight Safety Foundation. 1967. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ Barnette, Michael (2008). Florida's Shipwrecks. Images of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7385-5413-6.

- ^ "Coast Guard Plane Feared Lost in Gulf". Star-News. Pasadena, CA. United Press International. 6 March 1967.

- ^ "Coast Guard Aviation Casualties". 15 June 1967. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ Freeze, Ken (7 August 1967). "Mt. Mars USCG HU-16E Crash". Jacksjoint.com. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Crash of a Grumman HUI-16A Albatross off Makassar: 5 killed | Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives". www.baaa-acro.com. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

- ^ "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 10 November 2009. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ^ Dorr, Robert F. (October 1991). "Albatross: Amphibious Airborne Angel". Air International. 41 (4): 193–201. ISSN 0306-5634.

- ^ Bridgman, Leonard, ed. (1958). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1958-59. London: Jane's All the World's Aircraft Publishing Co. Ltd. pp. 311–312.

- ^ Mutza, Wayne (1996). Grumman Albatross: A History of the Legendary Seaplane. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 0-88740-913-X.

- ^ Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Flight test report". Archived from the original on 2012-12-08. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

Further reading

[edit]- Núñez Padin, Jorge Felix (2009). Núñez Padin, Jorge Felix (ed.). JRF Goose, PBY Catalina, PBM Mariner & HU-16 Albatros. Serie Aeronaval (in Spanish). Vol. 25. Bahía Blanca, Argentina: Fuerzas Aeronavales. ISBN 9789872055745. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-01-26.

- "Pentagon Over the Islands: The Thirty-Year History of Indonesian Military Aviation". Air Enthusiast Quarterly (2): 154–162. n.d. ISSN 0143-5450.

External links

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

- Historical Aircraft page on Northrop Grumman Web Site

- HU-16 history, including other designations

- The Grumman Albatross Site

- Summary at Coast Guard Historian's site

- The Grumman Albatross – A Spotter’s Guide

USAF amphibious aircraft designations | |

|---|---|

| Observation Amphibian "OA" (1925-1947) | |

| Amphibian "A" (1948-1962) | |

Not to be confused with the Attack or Aerial target sequences. | |

| Patrol |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patrol Bomber |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Patrol Torpedo Bomber |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1 Not assigned · 2 Designation reused | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Utility (J) (1935–1955) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utility transport (JR) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Utility (U) (1955–1962) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

United States tri-service utility aircraft designations post-1962 | |

|---|---|

| Main sequence | |

| Non-sequential | |

| Related designations | |

1 Not assigned • 2 Designated to hide the true role • 3 Assigned to multiple types | |

Canadian Armed Forces post-1968 unified aircraft designations | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical Sequence |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Role |

| ||||||||||||||||||

1 Not assigned | |||||||||||||||||||

Brazilian Air Force aircraft designations | |

|---|---|

| Attack (A) | |

| Cargo (C) | |

| Electronic (E) | |

| Fighter (F) | |

| Helicopter (H) | |

| Liaison (L) | |

| Maritime (M) | |

| Observation (O) | |

| Patrol (P) | |

| Reconnaissance (R) | |

| Search & rescue (S) | |

| Trainer (T) | |

| Utility (U) | |

| Glider (Z) | |

Designations carried over from American designation systems are not included unless the designations were modified. | |