Henry Billings Brown | |

|---|---|

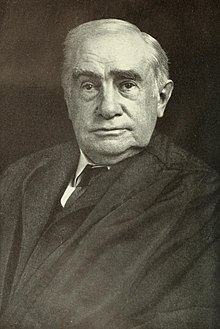

Brown's portrait by Frances Benjamin Johnston, 1905 | |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office January 5, 1891 – May 28, 1906[1] | |

| Nominated by | Benjamin Harrison |

| Preceded by | Samuel Freeman Miller |

| Succeeded by | William Henry Moody |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan | |

| In office March 19, 1875 – December 29, 1890 | |

| Nominated by | Ulysses S. Grant |

| Preceded by | John W. Longyear |

| Succeeded by | Henry Harrison Swan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 2, 1836 Lee, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | September 4, 1913 (aged 77) Bronxville, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Caroline Pitts

(m. 1864; died 1901)Josephine Tyler (m. 1904) |

| Education | Yale University (BA) Harvard University |

| Signature | |

Henry Billings Brown (March 2, 1836 – September 4, 1913) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1891 to 1906.

Although a respected lawyer and U.S. District Judge before ascending to the high court, Brown is harshly criticized for writing the majority opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson, an opinion widely regarded as one of the most ill-considered decisions ever issued by the Court, which upheld the legality of racial segregation in public transportation. Plessy legitimized existing state laws establishing racial segregation, and provided an impetus for later segregation statutes. Legislative achievements won during the Reconstruction Era were erased through Plessy's "separate but equal" doctrine.[2]

Brown was born in South Lee, Massachusetts, the son of Mary Tyler and Billings Brown, and grew up in Massachusetts and Connecticut. His was a New England merchant family, as his family was of entire English Puritan descent, emigrating following the Puritan migration to New England (1620–1640). The first ancestor who arrived was Edward Brown, settling in Ipswich, Massachusetts.[3] He attended Monson Academy, Monson, MA and entered Yale College at 16. There he was a member of Alpha Delta Phi fraternity and was elected to membership in Phi Beta Kappa. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree there in 1856. Among his undergraduate classmates were Chauncey Depew, later a U.S. Senator from New York, and David Josiah Brewer, who became Brown's colleague on the Supreme Court. Depew roomed across the hall from Brown for three years in Old North Middle Hall, and remembered "a feminine quality [about Brown] which led to his being called Henrietta" by classmates in his all-male college.[4] After a yearlong tour of Europe, Brown studied law with Judge John H. Brockway in Ellington, Connecticut, but his refusal to participate in a local religious revival made life there unpleasant for him.[5] He left Ellington to pursue legal studies, with a year at Yale Law School, and a semester at Harvard Law School.

Admitted to the Michigan Bar in 1860, Brown's early law practice was in Detroit, Michigan, where he specialized in admiralty law as it applied to shipping on the Great Lakes. In addition to his private law practice, at times between 1861 and 1868 Brown served as Deputy U.S. Marshal, Assistant United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan, and to fill an opening was appointed judge of the Wayne County Circuit Court in Detroit, although he only served briefly in that position and lost an election for a full term.[6] He then became a partner specializing in admiralty law in the firm of Newberry, Pond & Brown, and practiced there for seven years. In 1872 Brown failed in an attempt to win the Republican nomination for a congressional seat.[7]

In 1864, Brown married Caroline Pitts, the daughter of a wealthy Michigan lumber merchant. They had no children. He did not serve in the Union Army during the Civil War, but like many well-to-do men instead hired a substitute soldier to take his place.

Brown kept diaries from his college days until his appointment as a federal judge in 1875. Now held in the Burton Historical Collection of the Detroit Public Library, they suggest that he was both genial and ambitious, but also depressed and doubtful about himself. As a child Brown attended his family's Congregational Church, and when married to his first wife he accompanied her to a Presbyterian Church, but he was generally uninterested in religious matters.

The death of Brown's father-in-law left Brown and his wife financially independent, so he was willing to accept the relatively low salary of a federal judge. On March 17, 1875, Brown was nominated by President Ulysses Grant to a seat on the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan left vacant by the death of John Wesley Longyear. Brown was confirmed by the United States Senate two days later and immediately received his commission.

Brown edited a collection of rulings and orders in important admiralty cases from inland waters,[8] and later compiled a case book on admiralty law for lectures at Georgetown University.[9] He also taught admiralty law classes at the University of Michigan Law School from 1860 to 1875, and medical jurisprudence at the Detroit Medical College (now the medical school of Wayne State University) from 1868 to 1871.[10] Brown received honorary doctoral degrees from the University of Michigan in 1887,[11] and from Yale University in 1891.[12]

Brown was nominated by President Benjamin Harrison as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court on December 23, 1890, to succeed Samuel Freeman Miller. Harrison, who had earlier considered Brown for a Supreme Court appointment following the death of Stanley Matthews the previous year, actively lobbied senators on Brown's behalf.[13] He was confirmed by the U.S. Senate by voice vote on December 29, 1890,[14] and was sworn into office on January 5, 1891.[1] In an autobiographical essay, Brown commented "While I had been much attached to Detroit and its people, there was much to compensate me in my new sphere of activity. If the duties of the new office were not so congenial to my taste as those of district judge, it was a position of far more dignity, was better paid and was infinitely more gratifying to one's ambition."[15]

As a jurist, Brown was generally against government intervention in business, and joined the majority opinion in Lochner v. New York (1905) striking down a limitation on maximum working hours. He did, however, support the federal income tax in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. (1895), and wrote for the Court in Holden v. Hardy (1898), upholding a Utah law restricting male miners to an eight-hour day.

Brown is best known, and widely criticized, for the 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, in which he wrote the majority opinion upholding the principle and legitimacy of "separate but equal" facilities for American blacks and whites. In his opinion, Brown argued that the recognition of racial difference did not necessarily violate constitutional principle. As long as equal facilities and services were available to all citizens, the "commingling of the two races" need not be enforced. Plessy, which provided legal support for the system of Jim Crow Laws, was effectively overruled by the Court in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. When issued, Plessy attracted relatively little attention, but in the late 20th century it came to be condemned, with maledictions falling on Brown for having written it.

We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it. The argument necessarily assumes ... that social prejudices may be overcome by legislation, and that equal rights cannot be secured to the negro except by an enforced commingling of the two races. We cannot accept this proposition. If the two races are to meet upon terms of social equality, it must be the result of natural affinities, a mutual appreciation of each other's merits, and a voluntary consent of individuals. (From Brown's majority opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 551 (1896))

Justice Brown authored the Court's 1901 opinions in DeLima v. Bidwell and Downes v. Bidwell, two of the Insular Cases, considering the status of territories acquired by the U.S. in the Spanish–American War of 1898.

|

Main article: Hale v. Henkel |

Brown expounded for the majority the powers accorded to the grand jury in Hale v. Henkel, a 1906 case where the defendant—a tobacco company executive—refused to testify to the grand jury on several grounds in a case based upon the Sherman Antitrust Act. This opinion, said to be among his best, was rendered March 12, 1906, only 10 weeks before his retirement.

In 1891 he paid $25,000 (equivalent to $848,000 in 2023) to the Riggs family for land at 1720 16th Street, NW, in Washington, D.C., hired Cornell architect William Henry Miller, and built a five-story, 18-room mansion for $40,000 (equivalent to $1,356,000 in 2023). He would live in this house, later known as the Toutorsky Mansion, until his death. Ironically—in light of Brown's racial attitudes—the house is now the embassy of the Republic of the Congo.

Brown's wife Caroline died in 1901. Three years later, Brown married a close friend of hers, the widow Josephine E. Tyler, who survived him.

Near the end of his years on the Court, Brown largely lost his eyesight. He retired from the Court on May 28, 1906, at the age of 70.

In April 1910, retired Justice Brown presented a talk to The Ladies' Congressional Club of Washington, D.C., entitled "Woman Suffrage". In it he advocated against extending the vote to women, arguing that no persons, male or female, have a natural right to the vote, and that for a litany of reasons women should not have the legal ability to participate in elections. From the perspective of the 21st century, the talk is full of risible assertions and clichés about the role of women in society.[16]

Brown died of heart disease on September 4, 1913, at a hotel in Bronxville, New York. He is buried next to his first wife in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit.

Despite Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown as a judge did not invariably vote against the interests of minority litigants. For example, in Ward v. Race Horse, Brown was the sole dissenter when the Court held that tribal hunting rights granted under an 1869 treaty with the Bannock Indians must yield to a state law prohibiting them. As to the Chinese Exclusion Act, Brown voted with the majority in United States v. Wong Kim Ark that a child born in the United States of Chinese parents was a U.S. citizen under the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.[a] Brown also voted with the majority in Wong Wing v. United States, in holding that Chinese persons allegedly in the United States illegally may not be imprisoned at hard labor without a trial pending deportation.[17] Brown also joined Justice David Brewer's dissent in Giles v. Harris, arguing Black Americans had a right to challenge voter suppression in federal court.[18]

Brown, a privileged son of the Yankee merchant class, was a reflexive social elitist whose opinions of women, African‐Americans, Jews, and immigrants now seem odious, even if they were unexceptional for their time. Brown exalted, as he once wrote, 'that respect for the law inherent in the Anglo‐Saxon race'. Although he was widely praised as a fair and honest judge, Plessy has irrevocably dimmed his otherwise creditable career. Though some may argue that Brown bears personal guilt for the racial evils Plessy helped make possible, others respond that Brown was a man of his day, noting that the decades of de jure discrimination that came after Plessy merely reflected the zeitgeist.[19]

Brown has been remembered as "a capable and solid, if unimaginative, legal technician."[20] One of his friends offered the faint praise that Brown's life "shows how a man without perhaps extraordinary abilities may attain and honour the highest judicial position by industry, by good character, pleasant manners and some aid from fortune".[21] His obituary in the New York Times stated that on the Supreme Court Brown "gained a reputation for the strictest impartiality"; that he was "courteous to counsel", "was noted for his willingness to admit that he had committed an error", and finally that "he was remarkably free from pride of opinion".[22]

Perhaps the public nadir of Brown's legacy occurred during the 2010 Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearings for then Solicitor General, and former Harvard Law School Dean, Elena Kagan, to be an associate justice of the Supreme Court. Kagan admitted that she did not know who Brown was, and her questioner, Republican Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, then mentioned Brown with disdain:[23]

Senator GRAHAM. And do you know — are you familiar with Justice Henry Billings Brown?

Ms. KAGAN. I feel as though I should be, but I'm going to say no.

Senator GRAHAM. Well, you don't want him to be your hero, trust me.

A Liberty ship named after him, the Henry B. Brown (hull number 938),[24] was launched in 1943 and scrapped in 1965.

Apart from a sepulchral monument in a Detroit cemetery, there are no known statues, named schools or buildings or institutions, or any other memorials to Brown. There has been no book-length biography published about him.