Roger Shepard | |

|---|---|

Shepard at the ASU SciAPP conference in March 2019 | |

| Born | Roger Newland Shepard January 30, 1929 Palo Alto, California, U.S. |

| Died | May 30, 2022 (aged 93) Tucson, Arizona, U.S. |

| Occupation | cognitive scientist |

| Notable work | Shepard elephant, Shepard tones |

Roger Newland Shepard (January 30, 1929 – May 30, 2022[1]) was an American cognitive scientist and author of the "universal law of generalization" (1987). He was considered a father of research on spatial relations. He studied mental rotation, and was an inventor of non-metric multidimensional scaling, a method for representing certain kinds of statistical data in a graphical form that can be comprehended by humans. The optical illusion called Shepard tables and the auditory illusion called Shepard tones are named for him.

Shepard was born January 30, 1929, in Palo Alto, California. His father was a professor of materials science at Stanford.[2] As a child and teenager, he enjoyed tinkering with old clockworks, building robots, and making models of regular polyhedra.[3]

He attended Stanford as an undergraduate, eventually majoring in psychology[3] and graduating in 1951.[4]

Shepard obtained his Ph.D. in psychology at Yale University in 1955 under Carl Hovland,[5] and completed post-doctoral training with George Armitage Miller at Harvard.[6]

Subsequent to this, Shepard was at Bell Labs and then a professor at Harvard before joining the faculty at Stanford University. Shepard was Ray Lyman Wilbur Professor Emeritus of Social Science at Stanford University.[7]

His students include Lynn Cooper, Leda Cosmides, Rob Fish, Jennifer Freyd, George Furnas, Carol L. Krumhansl, Daniel Levitin, Michael McBeath, and Geoffrey Miller.[8]

In 1997, Shepard was one of the founders of the Kira Institute.[9]

|

Main article: Universal law of generalization |

Shepard began researching mechanisms of generalization while he was still a graduate student at Yale:[3]

I was now convinced that the problem of generalization was the most fundamental problem confronting learning theory. Because we never encounter exactly the same total situation twice, no theory of learning can be complete without a law governing how what is learned in one situation generalizes to another.

Shepard and collaborators "mapped" large sets of stimuli using the rank order of likelihood that a person or organism would generalize the response to Stimulus A and give the same response to Stimulus B. To use an example from Shepard's 1987 paper proposing his "Universal law of generalization": will a bird "generalize" that it can eat a worm slightly different from a previous worm that it found was edible?[10]

Shepard used geometric and spatial metaphors to map a psychological space where "distances" between different stimuli were larger or smaller depending on whether the stimuli were, respectively, less or more similar.[11] These imaginary distances are interesting because they permit mathematical inferences: the "exponential decay" in response to stimuli based on the distance holds valid for a wide range of experiments with human beings and with other organisms.[12]

In 1958, Shepard took a job at Bell Labs, whose computer facilities made it possible for him to expand earlier work on generalization. He reports, "This led to the development of the methods now known as non-metric multidimensional scaling – first by me (Shepard, 1962a, 1962b) and then, with improvements, by my Bell Labs mathematical colleague Joseph Kruskal (1964a, 1964b)."[3]

According to the American Psychological Association, "nonmetric multidimensional scaling .. has provided the social sciences with a tool of enormous power for uncovering metric structures from ordinal data on similarities."[13]

Awarding Shepard its Rumelhart Prize in 2006, the Cognitive Science Society called non-metric multidimensional scaling a "highly influential early contribution," explaining that:[7]

This method provided a new means of recovering the internal structure of mental representations from qualitative measures of similarity. This was accomplished without making any assumptions about the absolute quantitative validity of the data, but solely based on the assumption of a reproducible ordering of the similarity judgements.

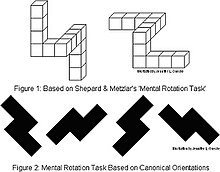

Inspired by a dream of three-dimensional objects rotating in space, Shepard began in 1968 to design experiments[3] to measure mental rotation. (Mental rotation involves "imagining how a two- or three-dimensional object would look if rotated away from its original upright position."[14])

The early experiments, in collaboration with Jacqueline Metzler, used perspective drawings of very abstract objects: "ten solid cubes attached face-to-face to form a rigid armlike structure with exactly three right-angled 'elbows,'" to quote their 1971 paper, the first report of this research.[15]

Shepard and Metzler were able to measure the speed with which subjects could imagine rotating these complicated objects. Later work by Shepard with Lynn A. Cooper illuminated the process of mental rotation further.[16] Shepard and Cooper also collaborated on a 1982 book (revised 1986) summarizing past work on mental rotation and other transformations of mental images.[17]

Reviewing that work in 1983, Michael Kubovy assessed its importance:[18]

Up to that day in 1968 [Shepard's dream about rotating objects], mental transformations were no more accessible to psychological experimentation than were any other so-called private experiences. Shepard transformed a compelling and familiar experience into an experimentally tractable problem by injecting it into a problem-task that admits of a correct and incorrect answer.

In 1990, Shepard published a collection of his drawings called Mind Sights: Original visual illusions, ambiguities, and other anomalies, with a commentary on the play of mind in perception and art.[19] One of these illusions ("Turning the tables," p. 48) has been widely discussed and studied as the "Shepard tabletop illusion" or "Shepard tables." Others, such as the figure-ground confusing elephant he calls "L'egs-istential quandary" (p. 79) are also widely known.[20]

Shepard is also noted for his invention of the musical illusion known as Shepard tones. He began his research on auditory illusions during his years at Bell Labs, where his colleague Max Mathews was experimenting with computerized music synthesis (Mind Sights, page 30.) Shepard tones give an illusion of constantly increasing pitch.[21] Musicians and sound-effect designers use Shepard tones to create some special effects.[22][23]

The Review of General Psychology named Shepard as one of the most "eminent psychologists of the 20th century" (55th on a list of 99 names, published in 2002).[24] Rankings for the list were based on journal citations, elementary textbook mentions, and nominations by members of the American Psychological Society.[25]

Shepard was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1977[26] and to the American Philosophical Society in 1999.[27] In 1995, he received the National Medal of Science.[7] The citation read:[28]

"For his theoretical and experimental work elucidating the human mind's perception of the physical world and why the human mind has evolved to represent objects as it does; and for giving purpose to the field of cognitive science and demonstrating the value of bringing the insights of many scientific disciplines to bear in scientific problem solving."

In 2006, he won the Rumelhart Prize.[7]