Socialist Labor Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | July 15, 1876 |

| Preceded by | Workingmen's Party of the United States |

| Headquarters | Mountain View, California |

| Newspaper | The Weekly People (1891–2011) |

| Membership (2006) | 77[1][needs update] |

| Ideology | Socialism Marxism Impossibilism Lassallism (until 1899) De Leonism (after 1899) |

| Political position | Left-wing |

| Colors | Red |

| Website | |

| slp.org | |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United States |

|---|

| Part of the Politics series on |

| De Leonism |

|---|

|

| Daniel De Leon |

| Marxism |

| Concepts |

| DeLeonists |

| Organizations |

| Socialism portal |

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)[2] is a political party in the United States. It was established in 1876, and was the first socialist party formed in the country.

Originally known as the Workingmen's Party of the United States, the party changed its name in 1877 to Socialistic Labor Party[3] and again sometime in the late 1880s to Socialist Labor Party.[4] The party was additionally known in some states as the Industrial Party or Industrial Government Party.[5] In 1890, the SLP came under the influence of Daniel De Leon, who used his role as editor of The Weekly People, the SLP's English-language official organ, to expand the party's popularity beyond its then largely German-speaking membership. Despite his accomplishments, De Leon was a polarizing figure among the SLP's membership. In 1899, his opponents left the SLP and merged with the Social Democratic Party of America to form the Socialist Party of America.

After his death in 1914, De Leon was followed as national secretary by Arnold Petersen. Critical of both the Soviet Union and the reformist wing of the Socialist Party of America, the SLP became increasingly isolated from the majority of the American Left. Its support increased in the 1950s and into the early 1960s, when Eric Hass was influential in the party, but slightly declined in the mid-1960s. The SLP experienced another increase in support in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but then subsequently declined at a fast rate with the party last nominating a candidate for president in 1976. In 2008, the party closed its national office and the party's newspaper The People ceased publications in 2011.

The party advocates "socialist industrial unionism", the belief in a fundamental transformation of society through the combined political and industrial action of the working class organized in industrial unions.

Organizational history

[edit]Forerunners and origins

[edit]In 1872, the International, a European-based international organization for a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist political groups and trade union organizations, moved its headquarters to New York City. It was in a weakened and disorganized state, having recently suffered a bitter internal struggle between Marxists, who supported trade union organization as preliminary to workers' revolution and anarchists, led by Mikhail Bakunin, who advocated the immediate revolutionary overthrow of organized government.[6]

In 1874, the members of the American-based International, led by cigarmaker Adolph Strasser and carpenter Peter J. McGuire joined forces with socialists from Newark and Philadelphia to form the ephemeral Social-Democratic Workingmen's Party of North America, the first Marxist political party in the United States.

Despite these organizational efforts, the socialist movement in America remained deeply divided over tactics. German immigrants preferred the parliamentary approach employed by Ferdinand Lassalle and the fledgling Social Democratic Party of Germany while longer-term residents of America usually supported a trade union orientation.[7] In April 1876, a preliminary conference took place in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania bringing together representatives of the union-oriented "Internationalists" and the electorally oriented "Lassalleans". The gathering agreed to issue a call for a Unity Congress to be held in July to establish a new political party.[8]

On Saturday, July 15, 1876, delegates from the remaining American sections of the First International gathered in Philadelphia and disbanded that organization.[9] The following Wednesday, July 19, the planned Unity Congress was convened, attended by seven delegates claiming to represent a membership of 3,000 in four organizations: the trade union-oriented Marxists of the now-disbanded International, and three Lassallean groups—the Workingmen's Party of Illinois, the Social Political Workingmen's Society of Cincinnati and the Social-Democratic Workingmen's Party of North America.[10] The organization formed by this Unity Convention was known as the Workingmen's Party of the United States (WPUS), and the native English-speaking Philip Van Patten was elected as the party's first "Corresponding Secretary", the official in charge of the day-to-day operations of the party.[10]

A number of socialist newspapers also emerged around this time, all privately owned, including Paul Grottkau's Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung, Joseph Brucker's Milwaukee Socialist and an English-language weekly also published in Milwaukee called The Emancipator.[11] German émigrés dominated the organization, although in Chicago Albert Parsons and G.A. Schilling maintained an active English-speaking section.[12]

In 1877, the Workingmen's Party met at Newark, New Jersey in a convention which changed the name of the organization to the Socialist Labor Party (generally rendered in English throughout the 1880s as "Socialistic Labor Party", a more stilted rendition of the German name of the group, Sozialistischen Arbeiter-Partei).[13] The SLP achieved its most notable electoral success in Chicago, where in 1878–1879, its candidates won slots for a state senator, three state representatives and four city aldermen.[14][15] In the 1879 Chicago mayoral election, the party's nominee received more than 20% of the vote.[15]

There was an upsurge of support for the new organization, reflected in the proliferation of the socialist press. Between 1876 and 1877, no fewer than 24 newspapers were established which either directly or indirectly supported the SLP.[16] Eight of these were English-language publications, including one daily, while 14 were in German, including seven dailies. Two more papers were published in Czech and Swedish, respectively.[16]

Just two years later, in the wake of an economic crisis, not one of the privately owned English newspapers had survived.[17] In 1878, the party established its own English-language paper, The National Socialist, but managed to keep the publication alive only one year.[17] The year 1878 saw the establishment of a more enduring newspaper: the German-language New Yorker Volkszeitung (New York People's News). The Volkszeitung included material by the best and the brightest of the German-American socialist movement, including Alexander Jonas, Adolph Douai, and Sergei Shevitch and Herman Schlüter; and quickly emerged as the leading voice of the SLP during the last decades of the 19th century.[17]

About this same time, the American anarchist movement gained strength, fueled by the economic crisis and strike wave of 1877. As socialist Frederic Heath recounted in 1900:

The line between Anarchism and Socialism was not at this time sharply drawn in the Socialist organizations, in spite of the fact of their being opposites. Both being critics and denouncers of the present system, however, they were able to work together. As a result of the brutalities of the militia and regulars in the railway strikes of 1877, a new plan was devised by the Chicago agitators. This found expression in the Lehr und Wehr Verein (teaching and defense society), an armed and drilled body of workmen pledged to protect the workers against the militia in a strike. ... The arms-bearing tactics were opposed by the Executive Committee of the SLP, the Secretary of which was Philip van Patten. A fight ensued between the Verbote, which was the weekly edition of the Arbeiter Zeitung, of Chicago, and the Labor Bulletin, the official party organ which Patten edited.[18]

The SLP suffered its first split in 1878. Members who were displeased with the exclusively political actionist turn of the party who wanted the group to focus more on organizing workers formed the International Labor Union. Members were not barred from belonging to both, but there was still some animosity between the two organizations.[19]

Amidst economic crisis and factional squabbling, membership in the SLP plummeted. As the 1870s drew to a close, the Socialistic Labor Party could count about 2,600 members—with at least one estimate substantially lower.[20]

In the 1880s

[edit]

The years 1880 and 1881 saw a new influx of political refugees from Germany, activists in the socialist movement fleeing the crackdown on radicalism launched with the Anti-Socialist Laws of 1878.[20] This influx of new German members, coming during a time of low ebb of the English-speaking membership, extended Germanic influence in the SLP. Excluded from the voting booth by their lack of citizenship status, many of the newcomers had little use for electoral politics. An SLP German militia sued on Second Amendment grounds to keep and bear arms in Chicago parades. However, the Supreme Court ruled against them in Presser v. Illinois.

The anarchist movement expanded rapidly with the debate over tactics between the electorally-oriented socialists and the direct action-oriented anarchists becoming ever more bitter. The 1881 SLP Convention in New York saw some of the party's anarchist members and one New York section split from the party to form a new party called the Revolutionary Socialist Labor Party as part of an International Workingmen's Association. The official organ of this short-lived splinter group was a newspaper called The Anarchist.[21]

In 1882, Johann Most, a former German Social Democrat turned Anarchist firebrand, came to the United States, further fueling the growth and militancy of the American anarchist movement. The SLP further divided the next year when Marxist Paul Grottkau was forced by the anarchists to resign as editor of the Chicago daily, the Arbeiter Zeitung. In his place August Spies was installed, a man later executed as part of the anti-anarchist repression which followed the Haymarket affair of May 1886.[22]

After a brief honeymoon period in the late 1870s had run its course, the SLP saw the departure of most of its English-speaking members. The party's English-language organ, Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement, appeared monthly from Detroit in the shadow of the powerful Chicago German-language radical press until it was finally discontinued altogether at the end of 1883. The party was so thoroughly German that it published the stenographic proceedings of its 1884 and 1885 National Conventions only in that language.[23] From 1885, the official organ of the party was a German-language weekly, Der Sozialist. No English-language SLP organ existed from the demise of the Bulletin in 1883 to the establishment of the Workingmen's Advocate in 1886.

The party's membership situation was so dismal that the English-speaking Corresponding Secretary of the organization, Philip Van Patten, left a suicide note in April 1883 and mysteriously disappeared. He later surfaced as a government employee, a socialist oppositionist no more.[24] Membership in the organization atrophied to just 1,500 by 1883.[25] What growth there was among the American radical movement was experienced by the rival anarchist organization, the International Working People's Association (IWPA), also sometimes referred to as the International Workingmen's Association.[26]

A split between the electorally oriented SLP and the revolution-minded IWPA, which took with it a good portion of the SLP's left-wing, including such prominent leaders as the English-speaking orator Albert Parsons and the German-speaking newspaper editor August Spies, began to develop early in the 1880s, with the split formalized by 1883, a year in which the SLP and the IWPA held competing conventions in Baltimore and Pittsburgh, respectively.[27] At its December 1883 Baltimore Convention, the SLP made a vain effort at reestablishing organizational unity with the IWPA, adopting a particularly radical "proclamation" in the name of the party and eliminating the position of National Secretary to allow the form of decentralization favored by the anarchists.[28]

The issue of violence proved an insurmountable barrier to unity between the SLP and the anarchist movement and as Paul Grottkau, Alexander Jonas and their co-thinkers began to again forcefully espouse the Marxist point of view in 1884, the SLP began to rebound. In March 1884, the SLP consisted of 30 sections and two years later it had doubled.[29] Three new privately owned English-language newspapers were briefly established, although none could achieve the critical mass of subscribers and advertising revenue necessary for survival.[29]

The SLP attempted to again make a foray into American electoral politics despite its still heavily German composition, joining forces with other labor organization into the United Labor Party to support Single Tax advocate Henry George in the 1886 New York City mayoral election.[30][31] The party remained almost completely separated from the English-speaking workers movement and longing for leaders who could traverse the seemingly insurmountable language barrier which limited the organization to a sort of Teutonic ghetto.

Throughout the decade of the 1880s, the SLP was based upon local "Sections" coordinated by a loose National Executive Committee based in New York City. It was not until 1889 that any move was made to establish intermediate state levels of organization.[32]

Relationship with the labor movement

[edit]The SLP did attempt to play an influence in the existing labor movement during the decade of the 1880s. As early as 1881, National Secretary Philip Van Patten joined the Order of the Knights of Labor, the leading national union of the day.[33] A decade later, the SLP retained a faith in the established trade union organizations to conduct their own affairs along a generally socialist course. In each issue of The People during 1891 the weekly affairs of the New York Central Labor Federation, the New York Central Labor Union, the Brooklyn Central Labor Federation, the Brooklyn Central Labor Union and the Hudson County, New Jersey (Jersey City) Central Labor Federation were covered in detail under the recurring headline "Parliaments of Labor". The doings of individual unions in the New York area and around the world were similarly covered in short summary.

Despite its active role as cheerleader and publicist, the SLP was unable to exert any sort of real influence in the Knights of Labor until it was already in steep decline toward the start of the 1890s, when it won effective control of the New York District Assembly of the K of L in 1893.[33] In that same year, socialist delegates to the governing General Assembly of the K of L were largely responsible for the defeat of Terence Powderly and his replacement by J. R. Sovereign as Grand Master Workman, the chief executive officer of the organization.[33]

So great was the SLP's influence that the newly elected Sovereign promised to appoint a member of the party as editor of the Journal of the Knights of Labor.[33] When he recanted on this pledge, a bitter feud erupted, ending with the December 1895 General Assembly refusing to seat de facto SLP party leader Daniel De Leon as a delegate from District Assembly 49, resulting in an outright break of the two organizations and withdrawal of the greater part of the New York district from the organization, thereby hastening the Knights of Labor's demise.[33]

Coming of Daniel De Leon

[edit]

The year 1890 has long been regarded as a watershed by the SLP as it marked the date when the organization came under the influence of Daniel De Leon.[34] A native of the South American island of Curaçao, De Leon had been resident in the United States for 18 years before he began to play a leading role in the American socialist movement. De Leon attended a Gymnasium in Hildesheim, Germany in the 1860s before studying at the University of Leyden, from which he graduated in 1872 at the age of 20.[35] De Leon was a brilliant student—well versed in history, philosophy and mathematics. He was also a linguist with few peers, possessing fluency in Spanish, German, Dutch, Latin, French, English and ancient Greek; and a reading knowledge of Portuguese, Italian and modern Greek.[36]

Upon graduation, De Leon immigrated to the United States, settling in New York City. There he made the acquaintance of a group of Cubans who sought the liberation of their native land and edited their Spanish-language newspaper.[37] De Leon paid the bills with a job teaching Latin, Greek and math at a school in Westchester, New York.[38] This teaching job enabled De Leon to finance his further education at Columbia Law School, from which he graduated with honors in 1878.[39] Thereafter, De Leon moved to Texas, where he practiced law for a time before returning to Columbia University in 1883 to take a position as a lecturer on Latin American diplomacy.[39]

De Leon seems to have been further politicized by the 1886 workers' campaign for the Eight-Hour Day and the brutal excesses of the police which came with it.[39] De Leon was on the committee which nominated Henry George to run for Mayor in that same year and he spoke in public several times on George's behalf during the course of the campaign.[39] De Leon participated in the first Nationalist Club in New York City, a group dedicated to advancing the socialist ideas expressed by Edward Bellamy in his extremely popular novel of the day, Looking Backward (1888).[39] De Leon was also deeply influenced by The Co-operative Commonwealth by Laurence Gronlund.[40]

The failings of the Nationalist Club movement to develop a viable program or strategy for winning political power left De Leon searching for an alternative. This he found in the scientific determinism underlying the writings of Karl Marx.[41] In the fall of 1890, De Leon abandoned his academic career to devote himself full-time to the SLP. He was engaged in the spring of 1891 as the party's "National Lecturer", traveling the entire country from coast to coast to speak on the SLP's behalf.[39] He was also named the SLP's candidate for Governor of New York in the fall of that same year, gathering a respectable 14,651 votes.[42]

As the historian Bernard Johnpoll notes, the SLP which Daniel De Leon joined in 1890 differed little from the organization which had been born at the end of the 1870s as it was largely a German-language organization located in an English-speaking country. Just 17 of the party's 77 branches used English as their basic language while only two members of the party's governing National Executive Committee spoke English fluently.[40] The arrival of an erudite, well-read and multilingual university lecturer with English fluency was seen as a great triumph for the SLP organization.

In the spring of 1891, De Leon was set to work as the National Organizer for the SLP. He pioneered for an English-speaking organization on a cross-country six-week tour to the West Coast and back in April and May.[43]

In 1892, De Leon was elected editor of The Weekly People, the SLP's English-language official organ.[38] He retained this important position without interruption for the rest of his life. De Leon never assumed the formal role of head of the organization, National Secretary, but was always recognized—by supporters and detractors alike—as the leader of the SLP through his tight editorial control of the official party press.

While increasing the exposure and popularity of the organization among the American-born during his editorial tenure, De Leon proved to be a polarizing figure among the SLP's membership during his editorial tenure as historian Howard Quint notes:

Even De Leon's opponents were usually willing to concede that he possessed a tremendous intellectual grasp of Marxism. Those who had suffered under his editorial lashings looked on him as an unmitigated scoundrel who took fiendish delight in character assassination, vituperation, and scurrility. But most of De Leon's contemporaries, and especially his critics, misunderstood him, just as he himself lacked understanding of people. He was not a petty tyrant who desired power for power's sake. Rather, he was a dogmatic idealist, devoted brain and soul to a cause, a zealot who could not tolerate heresy or backsliding, a doctrinaire who would make no compromise with principles. For this strong-willed man, this late nineteenth-century Grand Inquisitioner of American socialism, there was no middle ground. You were either a disciplined and undeviating Marxist or no socialist at all. You were either with the mischief-making, scatterbrained reformers and 'labor fakirs' or you were against them. You either agreed on the necessity of uncompromising revolutionary tactics or you did not, and those falling into the latter category were automatically expendable as far as the Socialist Labor Party was concerned.[44]

Early electoral politics

[edit]The Socialist Labor Party advocated a two-pronged attack against capitalism, including both economic and political components—trade unions and electoral campaigns.

The SLP ran candidates under its own name for the first time in the New York elections of 1886, in which it put forward a full ticket headed by J. Edward Hall as its gubernatorial nominee and Alexander Jonas as its candidate for Mayor of New York.[45] Fewer than 3,000 votes were cast for this ticket throughout the entire state of New York, a result so disheartening that the German language party paper the New Yorker Volkszeitung and some prominent party leaders advocated abandonment of electoral campaigns for the time being.[46] The National Convention of 1889 upheld the policy of political action and the SLP was again active in the New York elections of 1890.[46]

In 1891, the party's electoral effort was led by the candidacy of Daniel De Leon for Governor of New York. De Leon polled a respectable 14,651 votes in the losing effort.[47]

The party nominated its first candidate for President of the United States in 1892, a decision made in September of that year at a national conference of the organization held at party headquarters in New York City,[48] despite the fact that the SLP's platform called for the abolition of the offices of President and Vice President. A pro-forma nominating convention was held in New York City in August, attended by just 8 delegates, at which candidates were named and a platform approved.[49] The party's ticket, featuring Boston camera manufacturer Simon Wing and New York electrician Charles H. Matchett, appeared on the ballot in just six states and drew a total of 21,512 votes.[50]

The number of votes gathered by the SLP ticket in 1892 constituted 0.18% of the national presidential vote that year. In percentage terms, the next two presidential elections of 1896 and 1900 were the most successful for the party as the SLP presidential candidate Charles H. Matchett received 0.26% of the national popular vote in 1896 and the party's candidate in 1900 Joseph Maloney received 0.29% of the popular vote nationwide. The latter's run was also the first time the SLP candidate was eclipsed by another socialist as Eugene Debs ran for the first time for the Socialist Party that year and received 0.6% of the national popular vote. Although SLP presidential candidates would go on to get higher vote totals in the mid-20th century, they would never again surpass 0.25% of the national vote.[51]

Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance

[edit]The main ideological principle of the SLP is revolutionary industrial unionism (also known as "socialist industrial unionism").

The early Socialist Labor Party, influenced by the father of the Social Democratic Party of Germany Ferdinand Lassalle, argued that the wage gains and improvements of conditions achievable by trade unions were insignificant and ephemeral. Only the capture of the state through the ballot box would enable a restructuring of the economy and society in anything resembling a permanent manner. So long as capitalism existed, wage gains here would be offset by the pressure of wage cuts there and incomes would be driven down to a subsistence minimum through the inexorable pressure of the market. Thus the political campaign for the capture of the state—winning office for the sake of winning power to enact change—was considered paramount.

For the Marxists who had come to dominate the Socialist Labor Party by the 1890s, this idea was exactly backwards. So long as fundamental economic relations between workers and employers remained unchanged, any alteration of the personnel of the state apparatus would be short-lived and would fall to nothing due to the wealth of the employers and their desire to preserve the existing economic order. The employing class controlled press and school and pulpit, the Marxists believed, their ideas of the "natural" order of things stuffed the heads of their willing political servitors. Only through collective action, trade union activities, could the working class begin to achieve consciousness of itself, the nature of the world and its purported historic mission.

However, what sort of trade unions would instill in the working class the ideas and drive to action that would lead to a revolutionary restructuring of the economic order? This was the central question, over which the SLP ultimately divided. On the one hand there were those who advocated the policy of "boring from within" the already-existing unions, attempting to win their memberships over to the idea of socialist reorganization of society through the force of propaganda and practical example. Ultimately, it was believed that enough individual unions could be won over that the entire trade union movement could be moved in a socialist direction.

Others rejected the existing network of craft unions as hopelessly reactionary bureaucracies, sometimes outright criminal in their administration, but never able to see beyond their own narrow and isolated concerns of wages, hours, recognition, and jurisdiction. A completely new, explicitly socialist industrial union structure was required, these individuals believed, an organization established on a broad basis uniting workers of different crafts in common cause. This new organization would gain the support of the working class when average workers at the bench witnessed the superiority of its form of organization and ideas in actual practice.

At the SLP's national convention of 1896, this issue came to a head with the formation of the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance, a party-sponsored industrial union federation founded to compete directly with the unions of the emerging American Federation of Labor and the declining Knights of Labor, which eventually became a part of the Industrial Workers of the World when that organization was founded in 1905.

Party split of 1899

[edit]

De Leon's opponents (primarily German-Americans, Jewish immigrants of various origins and trade unionists led by Henry Slobodin and Morris Hillquit) left the SLP in 1899. They later merged with the Social Democratic Party of America, headed by Victor L. Berger and Eugene V. Debs to form the Socialist Party of America.

20th century

[edit]In July 1908, the SLP briefly made national news with the nomination of Martin R. Preston, a convicted killer serving a 25-year prison sentence in Nevada, for President of the United States.[52] Making the nomination on the convention floor was party leader Daniel De Leon himself, who noted that Preston had "acted as the protector of defenseless girls" during a strike and had killed a restaurateur who had threatened him with death.[52] Despite the fact that the 32-year-old Preston was under the constitutionally mandated presidential age of 35, he was nonetheless unanimously nominated by the New York convention, which immediately notified him of their selection by telegram.[52] However, Preston declined the nomination,[53] leaving the SLP's National Executive Committee to name a new standard-bearer for the November election.

Arnold Petersen became national secretary for most of the 20th century from the death of De Leon in 1914 to 1969.

The SLP, always critical of both the Soviet Union and of the Socialist Party's "reformism", became increasingly isolated from the majority of the American Left.[54] The party had always advocated what they considered the purist socialism in its program, arguing that other parties had abandoned Marxism and became either fan clubs for dictators or merely a radical wing of the Democratic Party.

The party experienced two growth spurts in the 20th century. The first occurred in the late 1940s. The presidential ticket, which had been receiving 15,000 to 30,000 votes, increased to 45,226 in 1944. Meanwhile, the aggregate nationwide totals for Senate nominees increased during this same period from an average in the 40,000 range to 96,139 in 1946 and 100,072 in 1948. The party's fortunes began to sag during the early 1950s and by 1954 the aggregate nationwide totals for Senate nominees was down to 30,577.

Eric Hass became influential in the SLP in the early 1950s. Hass, the nominee for president in 1952, 1956, 1960 and 1964, played a major role in rebuilding the SLP. He authored the booklet "Socialism: A Home Study Course". Hass increased the party's nationwide totals and recruited many local candidates. His vote for president increased from 30,250 in 1952 to 47,522 in 1960 (a 50% increase). Although his total slipped to 45,187 in 1964, Hass outpolled all other third-party candidates—the only time this happened to the SLP. Aggregate nationwide totals for Senate nominees increased throughout the late 1960s, hitting 112,990 in 1972.

The increased interest in the SLP in the late 1960s was not a permanent growth spurt. New recruits subscribed to the anti-authoritarian views of the time and wanted their voices to have an equal status with the old-time party workers. Newcomers felt that the party was too controlled by a small clique, resulting in widespread discontent. The SLP nominated its last presidential candidate in 1976, and has run few campaigns since then. In 1980, members of the SLP in Minnesota, claiming that the party had become bureaucratic and authoritarian in its internal party structure, split from the party and formed the New Union Party.

21st century

[edit]The SLP began having trouble funding their newspaper The People, so frequency was changed from monthly to bi-monthly in 2004. However, that did not save the paper from collapse and it was suspended as of March 31, 2008. An online version, published quarterly, ceased publication in 2011. As of January 2007, the party had 77 members-at-large as well as seven sections of which four (San Francisco Bay Area, Wayne County, Cleveland and Portland) held meetings, with an average attendance of 3–6 members.[1] The SLP closed its national office on September 1, 2008.[55]

Legacy

[edit]De Leon and the SLP helped to found the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905. They soon had a falling out with the element that they termed "the bummery" and left to form their own rival union, also called the Industrial Workers of the World, based in Detroit. De Leon died in 1914[54] and with his passing this organization lost its central focus. This body was renamed the Workers International Industrial Union (WIIU) and declined into little more than SLP members. The WIIU was wound up in 1924. Famed author Jack London was an early member of the Socialist Labor Party, joining in 1896. He left in 1901 to join the Socialist Party of America.

The American businessman and middleman for the Soviet Union Armand Hammer was said to be named after the "arm and hammer" graphic symbol of the SLP, in which his father Julius had a leadership role.[56] Late in his life, Hammer confirmed that the story contained the true origin of his given name.[57]: 16

The science fiction writer Mack Reynolds, who wrote one of the first Star Trek novels, was an active member of the SLP (his father Verne L. Reynolds was twice the SLP's candidate for vice president). His fiction often deals with socialist reform and revolution as well as socialist utopian thought and his characters often use De Leonite terminology such as "industrial feudalism".[58]

National Conventions

[edit]| Convention | Location | Date | Notes and references |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st National Congress | Philadelphia, PA | July 6, 1872 | First congress of the International Workingmen's Association in America (IWA), which formed the North American Federation of the International Workingmen's Association (NAF IWA) |

| 2nd National Congress | Philadelphia, PA | April 11, 1874 | Second congress of the International Workingmen's Association in America (IWA); split created Social-Democratic Workingmen's Party of North America (SDWP) |

| Congress | Philadelphia, PA | July 4–6, 1875 | First and only congress of the SDWP Platform and constitution of the Social-Democratic Workingmen's Party of North America |

| Union Congress | Philadelphia, PA | July 19–22, 1876 | First and only congress of the Workingmen's Party 1. Original edition of the proceedings. 2. The 1976 centennial edition edited and annotated by Philip S. Foner. |

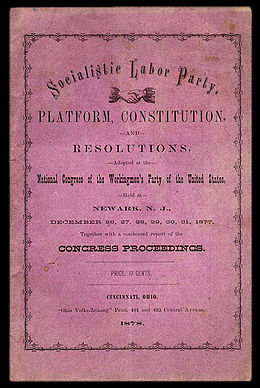

| National Congress | Newark, NJ | December 26–31, 1877 | Name changed to Socialistic Labor Party; Documents & Proceedings. |

| 2nd National Convention | Allegheny, PA | December 26, 1879 – January 1, 1880 | Documents & Condensed Proceedings. |

| 3rd National Convention | New York City | December 26–29, 1881 | Proceedings in German from the New Yorker Volkszeitung. |

| 4th National Convention | Baltimore, MD | December 26–28, 1883 | Proceedings in German; some pages blacked out. |

| 5th National Convention | Cincinnati, OH | October 5–8, 1885 | Proceedings in German. |

| 6th National Convention | Buffalo, NY | September 17–20, 1887 | Proceedings. |

| 7th National Convention (regular) | Chicago, IL | October 12–17, 1889 | Upholds political action. Account of Proceedings in Workmens Advocate. |

| 7th National Convention (dissident) | Chicago, IL | September 28–October 2, 1889 | Proceedings. |

| 1892 Nominating Convention | New York City | August 27, 1892 | Attended by just 8 delegates, who nominated presidential slate and approved platform. |

| 8th National Convention | Chicago, IL | July 2–5, 1893 | Proceedings as reported in The People. |

| 9th National Convention | New York City | July 4–10, 1896 | Establishes Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance. Proceedings. |

| 10th National Convention (regular) | New York City | June 2–8, 1900 | Reviews 1899 party split. Proceedings. |

| 10th National Convention (dissident) | Rochester, NY | January 27–February 2, 1900 | No stenographic record published. |

| 11th National Convention | New York City | July 2–7, 1904 | Microfilm of the typescript is available from the Wisconsin Historical Society. |

| 12th National Convention | New York City | July 2–7, 1908 | No stenographic record published. |

| 13th National Convention | New York City | April 1912 | No stenographic record published. Nomination was made on April 9. |

| 14th National Convention | New York City | April 29–May 3, 1916 | No stenographic record published. Platform. |

| 15th National Convention | New York City | May 5–10, 1920 | Proceedings. |

| 16th National Convention | New York City | May 10–13, 1924 | Proceedings. |

| 17th National Convention | New York City | May 12–14, 1928 | Proceedings. |

| 18th National Convention | New York City | April 30–May 2, 1932 | Proceedings p. 1, Proceedings p. 2. |

| 19th National Convention | New York City | April 25–28, 1936 | Proceedings p. 1, Proceedings p. 2. |

| 20th National Convention | New York City | April 27–30, 1940 | Proceedings p. 1, Proceedings p. 2. |

| 21st National Convention | New York City | April 29–May 2, 1944 | Proceedings. |

| 22nd National Convention | New York City | May 1–3, 1948 | Proceedings. |

| 23rd National Convention | New York City | May 3–5, 1952 | Proceedings. |

| 24th National Convention | New York City | May 5–7, 1956 | Platform. |

| 25th National Convention | New York City | May 7–9, 1960 | Proceedings. |

| 26th National Convention | New York City | May 2–4, 1964 | Proceedings. |

| 27th National Convention | Brooklyn, NY | May 4–7, 1968 | Proceedings. |

| 28th National Convention | Detroit, MI | April 8–11, 1972 | Platform. |

| 29th National Convention | Southfield, MI | February 7–11, 1976 | Proceedings. |

| 30th National Convention | Chicago, IL | May 28–June 1, 1977 | Proceedings. |

| 31st National Convention | Philadelphia, PA | May 26–31, 1978 | Proceedings; no pdf available. |

| 32nd National Convention | Milwaukee, WI | July 1979 | Proceedings; no pdf available. |

| 33rd National Convention | Milwaukee, WI | June 27–July 1, 1980 | Proceedings; no pdf available. |

| 34th National Convention | Milwaukee, WI | July 1981 | Proceedings; no pdf available. |

| 35th National Convention | Milwaukee, WI | August 1982 | Proceedings; no pdf available. |

| 36th National Convention | Akron, OH | July 18–23, 1983 | Proceedings; no pdf available. Platform. |

| 37th National Convention | Akron, OH | July 1985 | Proceedings; no pdf available. |

| 38th National Convention | Akron, OH | July 27–31, 1987 | Proceedings; no pdf available. |

| 39th National Convention | Santa Clara, CA | April 29–May 3, 1989 | Proceedings. |

| 40th National Convention | Santa Clara, CA | April 28–30, 1991 | Proceedings. |

| 41st National Convention | Santa Clara, CA | May 1–4, 1993 | Proceedings. |

| 42nd National Convention | Santa Clara, CA | July 15–18, 1995 | Proceedings. |

| 43rd National Convention | Santa Clara, CA | May 2–5, 1997 | Proceedings. |

| 44th National Convention | Santa Clara, CA | April 9–12, 1999 | Proceedings. |

| 45th National Convention | Santa Clara, CA | June 1–4, 2001 | Proceedings. |

| 46th National Convention | Santa Clara, CA | July 9–11, 2005 | Proceedings. |

| 47th National Convention | Santa Clara, CA | July 14–16, 2007 | Proceedings. |

Secretaries of the party

[edit]| Name | Tenure | Title |

|---|---|---|

| Philip Van Patten | July 1876–April 1883 | Corresponding Secretary |

| Schneider | April–October 1883 | Corresponding Secretary |

| Hugo Vogt | October–December 1883 | Corresponding Secretary |

| None | December 1883–March 1884 | (Executive position abolished) |

| Wilhelm Rosenberg | March 1884–October 1889 | Corresponding and Financial Secretary |

| Benjamin J. Gretsch | October 1889–October 1891 | National Secretary |

| Henry Kuhn | 1891–1906 | National Secretary |

| Frank Bohn | 1906–1908 | National Secretary |

| Henry Kuhn | 1908 (pro tem) | National Secretary |

| Paul Augustine | 1908–1914 | National Secretary |

| Arnold Petersen | 1914–1969 | National Secretary |

| Nathan Karp | 1969–1980 | National Secretary |

| Robert Bills | 1980–2023 | National Secretary |

Presidential tickets

[edit]All election results taken from Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections and Vote for presidential and vice presidential candidates of the Socialist Labor Party.

Notable members

[edit]- John J. Ballam

- J. Mahlon Barnes

- Ella Reeve Bloor

- Frank Bohn

- George Boomer

- Louis B. Boudin

- Abraham Cahan

- John C. Chase

- Maximilian Cohen

- James Connolly

- Georgia Cozzini

- Daniel De Leon

- Solon De Leon

- Adolph Douai

- Benjamin Feigenbaum

- Louis C. Fraina

- Paul Grottkau

- Julius Gerber

- Margaret Haile

- J. Edward Hall

- Benjamin Hanford

- Job Harriman

- Caleb Harrison

- Eric Hass

- Max S. Hayes

- Morris Hillquit

- Isaac Hourwich

- Frank Johns

- Olive M. Johnson

- Antoinette Konikow

- William Ross Knudsen

- Joseph A. Labadie

- Algernon Lee

- Jack London

- Meyer London

- William Mailly

- Charles Matchett

- James H. Maurer

- P. J. McGuire

- Thomas J. Morgan

- Kate Richards O'Hare

- Albert Parsons

- Arnold Petersen

- Patrick L. Quinlan

- Arthur E. Reimer

- Mack Reynolds

- Verne L. Reynolds

- Wilhelm Rosenberg

- Lucien Sanial

- George A. Schilling

- Sergei Shevitch

- Algie Martin Simons

- Henry Slobodin

- August Spies

- Adolph Strasser

- Philip Van Patten

- Leslie White

- Morris Winchevsky

- Simon Wing

Party press

[edit]Party-owned

[edit]- Vorbote (The Warning) (1874–1924) – Chicago weekly. Predated the SLP, party organ 1876–1878. Broke with SLP for anarchism in the early 1880s.

- Arbeiter Stimme (Worker's Voice) (1876–1878) – New York City weekly. Predated the SLP under the title Sozial-Demokrat. New York Public Library holds master negative film.

- The Labor Standard (April 1876–December 1881) – New York City. Originally organ of the Social-Democratic Workingmen's Party of North America under title The Socialist. New York Public Library holds master negative film.

- The Social Democrat (c. 1877) – New York daily.

- The National Socialist (May 1878 – 1879) – Cincinnati official organ with John McIntosh as editor.

- Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement (1879–1883) – published in Detroit and New York City.

- Der Sozialist (1885–1892) – German language. Published in New York City.

- Vorwärts (Forward) (1892–1932) – published in New York City. Broke with SLP in 1899 and became privately owned publication.

- The Workmen's Advocate (1885–1891) – originally published by the New Haven (CT) Trades Council. Official organ of SLP from November 21, 1886. Subscription list taken over by The People in 1891.

- The People (1891–2011) – published in New York City by New Yorker Volkszeitung on behalf of the SLP. Party-owned from 1899. Later moved to Palo Alto, CA.

- Pittsburgher Volkszeitung (c. 1891) – German language. Pittsburgh weekly.

Privately owned

[edit]English

[edit]- Advance (1896–1902) – San Francisco weekly. Wisconsin Historical Society holds master negative film.

- The Echo (c. 1877) – Boston weekly.

- Emancipator (c. 1877) – Cincinnati and Milwaukee weekly.

- Emancipator (1894) – Cleveland weekly.

- The Evening Telegram (c. 1884) – New Haven weekly.

- Lawrence Labor (1896) – Lawrence, MA weekly.

- The Liberator (1896–1897)

- Manchester Labor (1896) – Manchester, NH weekly.

- Ohio Labor (1895–1896) – Toledo weekly.

- Philadelphia Labor (1893–1894) – Philadelphia weekly.

- Quincy Labor (1895) – Quincy, IL weekly

- Rochester Labor (1896) – Rochester, NY weekly

- Rochester Socialist (1898) – Rochester, NY monthly.

- St. Louis Labor (1893–1928) – St. Louis daily. Broke with SLP circa 1897.

- San Antonio Labor (1894–1896) – San Antonio weekly.

- San Francisco Truth (c. 1884) – San Francisco weekly.

- Savannah Labor (1895) – Savannah, GA weekly.

- The Socialist (c. 1877) – Detroit weekly.

- The Socialist Alliance (1898) – Chicago weekly.

- The Star (c. 1877) – St. Louis daily.

- The Times (c. 1877) – Indianapolis weekly.

- The Tocsin (?–1899) – Minneapolis weekly.

- The Truth (1898) – Davenport, IA. Bilingual English and German.

- The Voice of the People (c. 1884) – New York City weekly.

- The Wage Worker (?–1899) – Kansas City weekly.

- Worcester Labor (1896) – Worcester, MA weekly.

- Workingmen's Ballot (c. 1877) – Boston weekly.

German

[edit]- Arbeiter von Ohio (Ohio Worker) (c. 1877) – Cincinnati weekly.

- Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung (Chicago Workers' News) (1876–1924) – Chicago daily paper, which published Vorbote.

- Chicagoer Sozialist (Chicago Socialist) (c. 1877) – Chicago daily.

- Chicagoer Volkszeitung (Chicago People's News) (c. 1877) – Chicago daily.

- Cleveland Volksfreund (Cleveland People's Friend) (1898) – Weekly.

- Freiheitsbanner (Freedom Flag) (c. 1877) – Cincinnati weekly.

- Illinois Volkszeitung (c. 1884)

- Milwaukee Sozialist (Milwaukee Socialist) (c. 1877) – Milwaukee daily. Predated the SLP.

- Die Neue Zeit (The New Era) (c. 1877) – Louisville and Chicago daily.

- New Yorker Volkszeitung (New York People's News) (1878–1932) – New York City daily. Broke with SLP in 1899, but continued publication until 1932.

- Ohio Volkszeitung (Ohio People's News) (c. 1877) – Cincinnati daily.

- Philadelphia Tageblatt (Philadelphia Daily Paper) (1877–1942) – Philadelphia daily. Broke with SLP at some point.

- Pittsburgher Arbeiter Zietung (c. 1890) – Pittsburgh weekly.

- Vorwärts! (Forward!) (1877–1878) – Milwaukee weekly. Wisconsin Historical Society holds master negative film.

- Vorwärts! (1893–1932) – Milwaukee daily with Victor Berger as editor. Broke with SLP in 1897. Wisconsin Historical Society holds master negative film.

- Vorwärts (Forward) (c. 1877) – Newark daily.

- Volksstimme des Westens (Voice of the People of the West) (c. 1877) – St. Louis daily.

Other languages

[edit]- Bulgarian

- Rabotnicheska Prosveta (Workers' Enlightenment) (1911–1969) – published in Granite City, IL and Detroit. Weekly.

- Czech

- Delnicke Listy (Voice of Labor) (c. 1877) – Cleveland weekly; predated the SLP.

- Pravda (Truth) (1898) – New York City weekly.

- Danish-Norwegian

- Arbejderen (The Worker) (1898) – Chicago weekly.

- Hungarian

- A Munkás (The Worker) (1910–1961) – New York City weekly. New York Public Library holds master negative film.

- Nepszava (People's Voice) (1898) – New York City weekly.

- Latvian

- Proletareets (The Proletarian) (1902–1911)

- Norwegian

- Den Nye Tid (The New Time) (c. 1877) – Chicago weekly.

- Polish

- Sila (The Force) (1898) – Buffalo weekly.

- Serbo-Croatian

- Radnička Borba (Workers' Struggle) (1907–1970) – published in New York, Cleveland and Detroit. Weekly, later semi-monthly.

- Swedish

- Arbetaren (The Worker) (1895–1928) – New York City weekly.

- Ukrainian

- Robitinychyi Holos (Workers' Voice) (1922–?) – New York City weekly.

- Yiddish

- Der Ermes (The Truth) (1895–1896) – Boston weekly.

- Arbeiter Zeitung (Workers' News) (1898) – New York City.

- Sources: Proceedings of the National Congress, 1877, pp. 16–17; Hillquit (1903), pp. 225, 242; American Labor Press Directory (1925), pp. 22–23; Library of Congress Chronicling America database.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Minutes, Reports, Resolutions etc (PDF). Forty-Seventh National Convention, Socialist Labor Party. 14–16 July 2007. p. 22.

- ^ "The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of the Constitution of the Socialist Labor Party of America adopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1924, 1928, 1932, 1936, 1940, 1944, 1948, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1964, 1968, 1972, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1993, 2001, 2005 and 2007) (cited February 18, 2016).

- ^ Socialistic Labor Party. Platform, Constitution, and Resolutions, Adopted at the National Congress of the Workingmen's Party of the United States, Held at Newark, New Jersey, December 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 1877. Together with a condensed report of the Congress Proceedings (Ohio Volks-Zeitung: Cincinnati, Ohio, 1878), pp. 26–27.

- ^ While the 1885 constitution and platform uses the term "socialistic" in the party name, the 1890 constitution and platform uses the term "socialist" in the party name. As both of these sources appear to be scans of original documents, it is safe to assume that this second name change necessarily occurred somewhere between 1885 and 1890. Unfortunately, the other sources provided by the SLP are not original scans and must be taken with a grain of salt. The Report of the Proceedings of the Sixth National Convention of the Socialistic Labor Party, Held at Buffalo, New York, September 17, 19, 20 & 21, 1887 (New York Labor News Company: New York, September 1887) would seem to indicate that party was still calling itself the Socialistic Labor Party in that year. While the majority of the .pdf is not an original scan, the cover page is. Yet, the 1887 platform (which is in no part an original scan) would seem to indicate that the party was calling itself the Socialist Labor Party by 1887. Likewise, the 1889 platform (reported in this non-scan copy of the Workmen's Advocate on October 26, 1889) employs the name Socialist Labor Party.

- ^ 20th Convention, section on Minnesota indicates that it was known as the Industrial Party in Minnesota from approximately 1920 to 1944, when the name was changed to Industrial Government Party. This lasted until the apparent dissolution of the Minnesota affiliate after the mass defection into the New Union Party in 1980. Additionally, the name Industrial Government Party was used in New York from approximately 1944 to 1954.

- ^ Frederic Heath, Social Democracy Red Book, (cover title: "Socialism in America.") Terre Haute, IN: Standard Publishing Co., 1900; pg. 32.

- ^ The division between German SDP-oriented newcomers and existing residents is mentioned in Heath, Social Democracy Red Book, pg. 33.

- ^ Frank Girard and Ben Perry, [The Socialist Labor Party, 1876–1991: A Short History](https://libcom.org/article/socialist-labor-party-1876-1991-short-history-frank-girard-and-ben-perry). Philadelphia, PA: Livra Books, 1991; pg. 3.

- ^ Girard and Perry, The Socialist Labor Party, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Girard and Perry, The Socialist Labor Party, pg. 4.

- ^ Heath, Social Democracy Red Book, pg. 33.

- ^ Heath, Social Democracy Red Book, pp. 33–34.

- ^ See, for example, the cover of the Platform und Constitution der Soz. Arbeiter-Partei published after the 1885 5th National Convention of the organization by the "National Executive Committee of the Socialistic Labor Party.

- ^ Dray, Philip (2010). There Is Power In A Union. New York: Doubleday. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-385-52629-6.

- ^ a b Ross, Jack (2015). The Socialist Party of America.

- ^ a b Morris Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States. New York: Funk and Wagnall Co., 1903; pg. 225.

- ^ a b c Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 227.

- ^ Heath, Social Democracy Red Book, pp. 34–35.

- ^ "International Labor Union" in Neil Schlager ed. St. James Encyclopedia of Labor History Worldwide Detroit: St. James Press/Gale Group/Thomson Learning, 2004. pp. 475–477.

- ^ a b Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 228.

- ^ Heath, Social Democracy Red Book, pg. 35.

- ^ Heath, Social Democracy Red Book, pg. 37.

- ^ See, for example: Offizielles Protokoll der 5. National-Konventin der Soz. Arbeiter-Partei von Nord-Amerika, abgehalten am 5., 6., 7. und 8. Oktober 1885 in Cincinnati, Ohio. New York: National Executive Committee of the Socialistic Labor Party, 1886.

- ^ Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 239.

- ^ Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 238.

- ^ For a contemporary example illustrating this confusing dual name for the largely German-language organization, see Richard T. Ely, Recent American Socialism. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University, 1886; pg. 21.

- ^ Ely, Recent American Socialism, pg. 26.

- ^ Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pp. 240–241.

- ^ a b Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 242.

- ^ Genovese, Frank C. (1991). "Henry George and Organized Labor: The 19th Century Economist and Social Philosopher Championed Labor's Cause, but Used Its Candidacy for Propaganda". The American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 50 (1): 113–127. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.1991.tb02500.x. ISSN 0002-9246. JSTOR 3487043.

- ^ "1886: The Men Who Would Be Mayor". City Journal. 2015-12-23. Retrieved 2021-11-08.

- ^ "State Organization: Circular of the New York City Committee of the SLP," Workmen's Advocate [New York], vol. 5, no. 25 (June 22, 1889), pg. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 293.

- ^ During the Arnold Petersen administration, the SLP passionately disavowed its history of the period before the arrival of De Leon, going so far as to publish a glossy illustrated "Golden Jubilee" volume celebrating the party's 50th anniversary in 1940. The pre-1890 SLP was sneeringly referred to as the "Socialistic Labor Party" (emphasis his) by Petersen in his party history contained in that volume. See: Socialist Labor Party: Golden Jubilee, 1890–1940 (cover title). New York: Socialist Labor Party, 1940.

- ^ Quint, Howard (1953). The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement: The Impact of Socialism on American Thought and Action, 1886–1901. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 142–143.

- ^ Olive M. Johnson, "Daniel De Leon — Our Comrade," in Daniel De Leon: The Man and His Work: A Symposium. New York: National Executive Committee of the Socialist Labor Party, 1919; pg. 88. Johnson acknowledges the 1904 pamphlet The Party Press as the source of much of her biographical information.

- ^ Historian Howard Quint refers to the nature of the unnamed paper as "revolutionary," which seems rather doubtful. Quint, Howard (1953). The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement: The Impact of Socialism on American Thought and Action, 1886–1901. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 143.

- ^ a b Johnson, "Daniel De Leon — Our Comrade," pg. 89.

- ^ a b c d e f Quint, Howard (1953). The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement: The Impact of Socialism on American Thought and Action, 1886–1901. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 143.

- ^ a b Bernard Johnpoll with Lillian Johnpoll, The Impossible Dream: The Rise and Demise of the American Left. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981; pg. 250.

- ^ Quint, Howard (1953). The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement: The Impact of Socialism on American Thought and Action, 1886–1901. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 144.

- ^ Quint, Howard (1953). The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement: The Impact of Socialism on American Thought and Action, 1886–1901. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 145.

- ^ De Leon spoke in the new state of Washington, in Portland, Oregon and four times in California. On his return trip, De Leon spoke in Denver, Topeka, Kansas City, St. Louis, Evansville, Indianapolis, Dayton, Pittsburgh, Scottsdale, Connellsville, Baltimore, Wilmington, Philadelphia and Camden over the course of a three-week period. See, "Socialist Labor Party". The People. Vol. 1, no. 3. 19 April 1891. p. 5.; and "Socialism in California". The People. Vol. 1, no. 4. 26 April 1891. p. 5.

- ^ Quint, Howard (1953). The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement: The Impact of Socialism on American Thought and Action, 1886–1901. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 145–146.

- ^ Morris Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 281.

- ^ a b Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 282.

- ^ The People [New York], November 29, 1891, cited in Quint, The Forging of American Socialism, pg. 145.

- ^ Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States, pg. 283.

- ^ "National Politics," Oakland Tribune, vol. 34, no. 30 (Aug. 28, 1892), pg. 5.

- ^ Quint, The Forging of American Socialism, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections, http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/

- ^ a b c "Convict Nominated: Socialist Labor Party Name Murderer for President," Tyrone [PA] Daily Herald, vol. XX, no. XX (July 6, 1908), pg. 1.

- ^ "Declines the Nomination for President on the Socialist Labor Ticket," Lima Daily News, vol. 12, no. 164 (July 9, 1908), pg. 3.

- ^ a b Kenneth T. Jackson, The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995; pg. 1083.

- ^ "Socialist Labor Party Closes Office". Ballot Access News. December 31, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ Epstein 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Steve Weinberg (1990). Armand Hammer, The Untold Story. Random House Value Publishing. ISBN 9780517062821.

- ^ Hough, Lawrence E. (1998). "Welcome to the Revolution: The Literary Legacy of Mack Reynolds". Utopian Studies. p. 324.

- Epstein, Edward Jay (1996). Dossier : the secret history of Armand Hammer (1st ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0679448020.

Further reading

[edit]- Seán Cronin, "The Rise and Fall of the Socialist Labor Party of North America," Saothar, vol. 3 (1977), pp. 21–33. in JSTOR.

- Darlington, Ralph (2008). Syndicalism and the Transition to Communism. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-3617-5.

- Nathan Dershowitz, "The Socialist Labor Party," Politics [New York], vol. 5, no. 3, whole no. 41 (Summer 1948), pp. 155–158.

- Philip S. Foner, The Great Labor Uprising of 1877. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1977.

- Philip S. Foner, The Workingmen's Party of the United States: A History of the First Marxist Party in the Americas. Minneapolis, MN: MEP Publications, 1984.

- Frank Girard and Ben Perry, Socialist Labor Party, 1876–1991: A Short History. Philadelphia: Livra Books, 1991.

- Howard Quint, The Forging of American Socialism: Origins of the Modern Movement: The Impact of Socialism on American Thought and Action, 1886–1901. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1953.

- L. Glen Seratan, Daniel Deleon: The Odyssey of an American Marxist. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979.

- James Andrew Stevenson, Daniel DeLeon: The Relationship of Socialist Labor Party and European Marxism, 1890-1914. PhD dissertation. University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1977.

- Charles M. White, The Socialist Labor Party, 1890-1903. PhD dissertation. University of Southern California, 1959.

See also

[edit]- Arm and hammer (symbol)

- British Socialist Labour Party

- Canadian Socialist Labour Party

- Socialist Studies

External links

[edit]- Contemporary SLP links

- Socialist Labor Party of America. Official party website.

- The People. Index of issues available in pdf, 1999–2008.

- Primary documents

- Bulletin of the Social Labor Movement. Vol 1. No. 14 (December 1880–January 1881). Full issue of rare official organ.

- "1891 Report of the NEC of the SLP". December 18, 1891.

- SLP Documents Downloads. Early American Marxism website. Index for assorted party documents in pdf format.

- Report of the Proceedings of the National Convention of the Socialistic Labor Party. Index for pdfs of proceedings of the party (1878–1887).

- Daniel DeLeon Online. Socialist Labor Party. Extensive collection of editorials and writings by Daniel De Leon in pdf format.

- Links relating to the historic SLP

- SLP Publications. Early American Marxism website. Partial, but lengthy list of official publications of the party.

- Early American Marxism website. Includes extensive party history.

- "DeLeon — A Sketch of His Socialist Career". Socialist Labor Party. Official party history of the party's most notable leader.

- Papers of the Socialist Labor Party of America: Records of the Socialist Labor Party of America; guide to a microfilm edition. User guide to the microfilm collection filmed by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

- Archives

- Socialist Labor Party Seattle Section Records. 1930–1962. 2.73 cubic feet (7 boxes).

- George E. Rennar Papers. 1933–1972. 37.43 cubic feet. Contains ephemera on the Socialist Labor Party.

| National Secretaries |

|

|---|---|

| Presidential tickets |

|

| Related topics | |

Current communist parties in the United States | |

|---|---|

| Marxist–Leninist (including Maoist and Hoxhaist parties) | |

| Trotskyist | |

| Other | |

This group includes only pre-1996 parties that fielded a candidate that won greater 0.1% of the popular vote in at least one presidential election | |||||||||||||||

| Presidential tickets that won at least one percent of the national popular vote (candidate(s) / running mate(s)) |

| ||||||||||||||

| Other notable left-wing parties | |||||||||||||||

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |