Sojourner Truth | |

|---|---|

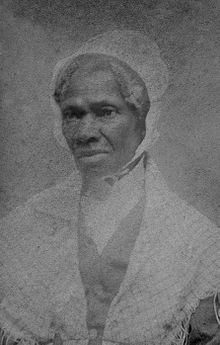

Truth, c. 1870 | |

| Born | Isabella Baumfree c. 1797 Swartekill, New York, U.S. |

| Died | (aged 86) Battle Creek, Michigan, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Abolitionist, human rights activist |

| Parent(s) | James Baumfree Elizabeth Baumfree |

Sojourner Truth (/soʊˈdʒɜːrnər, ˈsoʊdʒɜːrnər/;[1] born Isabella Baumfree; c. 1797 – November 26, 1883) was an American abolitionist and activist for African-American civil rights, women's rights, and alcohol temperance.[2] Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son in 1828, she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man.

She gave herself the name Sojourner Truth in 1843 after she became convinced that God had called her to leave the city and go into the countryside "testifying to the hope that was in her."[3] Her best-known speech was delivered extemporaneously, in 1851, at the Ohio Women's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. The speech became widely known during the Civil War by the title "Ain't I a Woman?", a variation of the original speech that was published in 1863 as being spoken in a stereotypical Black dialect, then more commonly spoken in the South.[4] Sojourner Truth, however, grew up speaking Dutch as her first language.[5][6][7]

During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army; after the war, she tried unsuccessfully to secure land grants from the federal government for formerly enslaved people (summarized as the promise of "forty acres and a mule"). She continued to fight on behalf of women and African Americans until her death. As her biographer Nell Irvin Painter wrote, "At a time when most Americans thought of slaves as male and women as white, Truth embodied a fact that still bears repeating: Among the blacks are women; among the women, there are blacks."[8]

A memorial bust of Truth was unveiled in 2009 in Emancipation Hall in the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center. She is the first African American woman to have a statue in the Capitol building.[9] In 2014, Truth was included in Smithsonian magazine's list of the "100 Most Significant Americans of All Time."[10]

Sojourner Truth once estimated that she was born between 1797 and 1800.[11] Truth was one of the 10 or 12[12] children born to James and Elizabeth Baumfree (or Bomefree). Her father was an enslaved man captured from present-day Ghana, while her mother – nicknamed "Mau-Mau Bet" – was the daughter of slaves captured from Guinea.[13] Colonel Hardenbergh bought James and Elizabeth Baumfree from slave traders and kept their family at his estate in a big hilly area called by the Dutch name Swartekill (just north of present-day Rifton), in the town of Esopus, New York, 95 miles (153 km) north of New York City.[14] Her first language was Dutch, and she continued to speak with a Dutch accent for the rest of her life.[15] Charles Hardenbergh inherited his father's estate and continued to enslave people as a part of that estate's property.[16]

When Charles Hardenbergh died in 1806, nine-year-old Truth (known as Belle), was sold at an auction with a flock of sheep for $100 (~$1,948 in 2023) to John Neely, near Kingston, New York. Until that time, Truth spoke only Dutch,[17] and after learning English, she spoke with a Dutch accent and not a stereotypical dialect.[18] She later described Neely as cruel and harsh, relating how he beat her daily and once even with a bundle of rods. In 1808 Neely sold her for $105 (~$2,003 in 2023) to tavern keeper Martinus Schryver of Port Ewen, New York, who owned her for 18 months. Schryver then sold Truth in 1810 to John Dumont of West Park, New York.[19] John Dumont raped her repeatedly, and considerable tension existed between Truth and Dumont's wife, Elizabeth Waring Dumont, who harassed her and made her life more difficult.[20]

Around 1815, Truth met and fell in love with an enslaved man named Robert from a neighboring farm. Robert's owner (Charles Catton, Jr., a landscape painter) forbade their relationship; he did not want the people he enslaved to have children with people he was not enslaving, because he would not own the children. One day Robert sneaked over to see Truth. When Catton and his son found him, they savagely beat Robert until Dumont finally intervened. Truth never saw Robert again after that day and he died a few years later.[21] The experience haunted Truth throughout her life. Truth eventually married an older enslaved man named Thomas. She bore five children: James, her firstborn, who died in childhood; Diana (1815), the result of a rape by John Dumont; and Peter (1821), Elizabeth (1825), and Sophia (c. 1826), all born after she and Thomas united.[22]

In 1799, the State of New York began to legislate the abolition of slavery, although the process of emancipating those people enslaved in New York was not complete until July 4, 1827. Dumont had promised to grant Truth her freedom a year before the state emancipation, "if she would do well and be faithful". However, he changed his mind, claiming a hand injury had made her less productive. She was infuriated but continued working, spinning 100 pounds (45 kg) of wool, to satisfy her sense of obligation to him.[17]

Late in 1826, Truth escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, Sophia. She had to leave her other children behind because they were not legally freed in the emancipation order until they had served as bound servants into their twenties. She later said, "I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right."[17][23]

She found her way to the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen in New Paltz, who took her and her baby in. Isaac offered to buy her services for the remainder of the year (until the state's emancipation took effect), which Dumont accepted for $20. She lived there until the New York State Emancipation Act was approved a year later.[17][24]

Truth learned that her son Peter, then five years old, had been sold by Dumont and then illegally resold to an owner in Alabama.[21] With the help of the Van Wagenens, she took the issue to the New York Supreme Court. Using the name Isabella van Wagenen, she filed a suit against Peter's new owner Solomon Gedney. In 1828, after months of legal proceedings, she got back her son, who had been abused by those who were enslaving him.[25][16] Truth became one of the first black women to go to court against a white man and win the case.[26][27][28] The court documents related to this lawsuit were rediscovered by the staff at the New York State Archives c. 2022.[25]

In 1827, she became a Christian and participated in the founding of the Methodist church of Kingston, New York.[29] In 1829, she moved to New York City and joined the John Street Methodist Church (Zion African Methodist Episcopal Church).[30]

In 1833, she was hired by Robert Matthews, also known as the Prophet Matthias, leader of a sect who identified with Judaism,[31] went to work for him as a housekeeper in the communal settlement, and became a member of the group.[32] In 1834, Matthews and Truth were charged with the murder of Elijah Pierson, but were acquitted due to lack of evidence and Truth's presentation of several letters confirming her reliability as a servant.[33] The trial then focused on the reported beating of his daughter of which he was found guilty and sentenced to three months and an additional thirty days for contempt of court. This event prompted Truth to leave the sect in 1835.[32] Afterwards, she retired to New York City until 1843.

In 1839, Truth's son Peter took a job on a whaling ship called the Zone of Nantucket. From 1840 to 1841, she received three letters from him, though in his third letter he told her he had sent five. Peter said he also never received any of her letters. When the ship returned to port in 1842, Peter was not on board and Truth never heard from him again.[16]

The year 1843 was a turning point for her. On June 1, Pentecost Sunday, she changed her name to Sojourner Truth. She chose the name because she heard the Spirit of God calling on her to preach the truth.[34][35] She told her friends: "The Spirit calls me, and I must go", and left to make her way traveling and preaching about the abolition of slavery.[36] Taking along only a few possessions in a pillowcase, she traveled north, working her way up through the Connecticut River Valley, towards Massachusetts.[24]

At that time, Truth began attending Millerite Adventist camp meetings. Millerites followed the teachings of William Miller of New York, who preached that Jesus would appear in 1843–1844, bringing about the end of the world. Many in the Millerite community greatly appreciated Truth's preaching and singing, and she drew large crowds when she spoke.[37] Like many others disappointed when the anticipated second coming did not arrive, Truth distanced herself from her Millerite friends for a time.[38][39]

In 1844, she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Florence, Massachusetts.[24] Founded by abolitionists, the organization supported women's rights and religious tolerance as well as pacifism. There were, in its four-and-a-half-year history, a total of 240 members, though no more than 120 at any one time.[40] They lived on 470 acres (1.9 km2), raising livestock, running a sawmill, a gristmill, and a silk factory. Truth lived and worked in the community and oversaw the laundry, supervising both men and women.[24] While there, Truth met William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and David Ruggles. Encouraged by the community, Truth delivered her first anti-slavery speech that year.

In 1845, she joined the household of George Benson, the brother-in-law of William Lloyd Garrison. In 1846, the Northampton Association of Education and Industry disbanded, unable to support itself.[17] In 1849, she visited John Dumont before he moved west.[16]

Truth started dictating her memoirs to her friend Olive Gilbert and in 1850 William Lloyd Garrison privately published her book, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: a Northern Slave.[17] That same year, she purchased a home in Florence for $300 and spoke at the first National Women's Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1854, with proceeds from sales of the narrative and cartes-de-visite captioned, "I sell the shadow to support the substance", she paid off the mortgage held by her friend from the community, Samuel L. Hill.[41][42][24]

In 1851, Truth joined George Thompson, an abolitionist and speaker, on a lecture tour through central and western New York State. In May, she attended the Ohio Women's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, where she delivered her famous extemporaneous speech on women's rights, later known as "Ain't I a Woman?". Her speech demanded equal human rights for all women. She also spoke as a former enslaved woman, combining calls for abolitionism with women's rights, and drawing from her strength as a laborer to make her equal rights claims.

The convention was organized by Hannah Tracy and Frances Dana Barker Gage, who both were present when Truth spoke. Different versions of Truth's words have been recorded, with the first one published a month later in the Anti-Slavery Bugle by Rev. Marius Robinson, the newspaper owner and editor who was in the audience.[43] Robinson's recounting of the speech included no instance of the question "Ain't I a Woman?", nor did any of the other newspapers reporting of her speech at the time. Twelve years later, in May 1863, Gage published another, very different, version. In it, Truth's speech pattern appeared to have characteristics of Black slaves located in the southern United States, and the speech was vastly different from the one Robinson had reported. Gage's version of the speech became the most widely circulated version, and is known as "Ain't I a Woman?" because that question was repeated four times.[44] It is highly unlikely that Truth's own speech pattern was like this, as she was born and raised in New York, and she spoke only upper New York State low-Dutch until she was nine years old.[45]

In the version recorded by Rev. Marius Robinson, Truth said:

I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman's rights. [sic] I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal. I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if a woman have a pint, and a man a quart – why can't she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, – for we can't take more than our pint'll hold. The poor men seems to be all in confusion, and don't know what to do. Why children, if you have woman's rights, give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won't be so much trouble. I can't read, but I can hear. I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well, if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept and Lazarus came forth. And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and the woman who bore him. Man, where was your part? But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.[46]

In contrast to Robinson's report, Gage's 1863 version included Truth saying her 13 children were sold away from her into slavery. Truth is widely believed to have had five children, with one sold away, and was never known to boast more children.[45] Gage's 1863 recollection of the convention conflicts with her own report directly after the convention: Gage wrote in 1851 that Akron in general and the press, in particular, were largely friendly to the woman's rights convention, but in 1863 she wrote that the convention leaders were fearful of the "mobbish" opponents.[45] Other eyewitness reports of Truth's speech told a calm story, one where all faces were "beaming with joyous gladness" at the session where Truth spoke; that not "one discordant note" interrupted the harmony of the proceedings.[45] In contemporary reports, Truth was warmly received by the convention-goers, the majority of whom were long-standing abolitionists, friendly to progressive ideas of race and civil rights.[45] In Gage's 1863 version, Truth was met with hisses, with voices calling to prevent her from speaking.[47] Other interracial gatherings of black and white abolitionist women had in fact been met with violence, including the burning of Pennsylvania Hall.

According to Frances Gage's recount in 1863, Truth argued, "That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody helps me any best place. And ain't I a woman?"[48] Truth's "Ain't I a Woman" showed the lack of recognition that black women received during this time and whose lack of recognition will continue to be seen long after her time. "Black women, of course, were virtually invisible within the protracted campaign for woman suffrage", wrote Angela Davis, supporting Truth's argument that nobody gives her "any best place"; and not just her, but black women in general.[49]

Over the next 10 years, Truth spoke before dozens, perhaps hundreds, of audiences. From 1851 to 1853, Truth worked with Marius Robinson, the editor of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Bugle, and traveled around that state speaking. In 1853, she spoke at a suffragist "mob convention" at the Broadway Tabernacle in New York City; that year she also met Harriet Beecher Stowe.[16] In 1856, she traveled to Battle Creek, Michigan, to speak to a group called the Friends of Human Progress.

Northampton Camp Meeting – 1844, Northampton, Massachusetts: At a camp meeting where she was participating as an itinerant preacher, a band of "wild young men" disrupted the camp meeting, refused to leave, and threatened to burn down the tents. Truth caught the sense of fear pervading the worshipers and hid behind a trunk in her tent, thinking that since she was the only black person present, the mob would attack her first. However, she reasoned with herself and resolved to do something: as the noise of the mob increased and a female preacher was "trembling on the preachers' stand", Truth went to a small hill and began to sing "in her most fervid manner, with all the strength of her most powerful voice, the hymn on the resurrection of Christ". Her song, "It was Early in the Morning", gathered the rioters to her and quieted them. They urged her to sing, preach, and pray for their entertainment. After singing songs and preaching for about an hour, Truth bargained with them to leave after one final song. The mob agreed and left the camp meeting.[51]

Abolitionist Convention – 1840s, Boston, Massachusetts: William Lloyd Garrison invited Sojourner Truth to give a speech at an annual antislavery convention. Wendell Phillips was supposed to speak after her, which made her nervous since he was known as such a good orator. So Truth sang a song, "I am Pleading for My people", which was her own original composition sung to the tune of Auld Lang Syne.[52]

Mob Convention – September 7, 1853: At the convention, young men greeted her with "a perfect storm", hissing and groaning. In response, Truth said, "You may hiss as much as you please, but women will get their rights anyway. You can't stop us, neither".[45] Sojourner, like other public speakers, often adapted her speeches to how the audience was responding to her. In her speech, Sojourner speaks out for women's rights. She incorporates religious references in her speech, particularly the story of Esther. She then goes on to say that, just as women in scripture, women today are fighting for their rights. Moreover, Sojourner scolds the crowd for all their hissing and rude behavior, reminding them that God says to "Honor thy father and thy mother".[53]

American Equal Rights Association – May 9–10, 1867: Her speech was addressed to the American Equal Rights Association, and divided into three sessions. Sojourner was received with loud cheers instead of hisses, now that she had a better-formed reputation established. The Call had advertised her name as one of the main convention speakers.[53] For the first part of her speech, she spoke mainly about the rights of black women. Sojourner argued that because the push for equal rights had led to black men winning new rights, now was the best time to give black women the rights they deserve too. Throughout her speech she kept stressing that "we should keep things going while things are stirring" and fears that once the fight for colored rights settles down, it would take a long time to warm people back up to the idea of colored women's having equal rights.[53]

In the second sessions of Sojourner's speech, she used a story from the Bible to help strengthen her argument for equal rights for women. She ended her argument by accusing men of being self-centered, saying: "Man is so selfish that he has got women's rights and his own too, and yet he won't give women their rights. He keeps them all to himself." For the final session of Sojourner's speech, the center of her attention was mainly on women's right to vote. Sojourner told her audience that she owned her own house, as did other women, and must, therefore, pay taxes. Nevertheless, they were still unable to vote because they were women. Black women who were enslaved were made to do hard manual work, such as building roads. Sojourner argues that if these women were able to perform such tasks, then they should be allowed to vote because surely voting is easier than building roads.

Eighth Anniversary of Negro Freedom – New Year's Day, 1871: On this occasion the Boston papers related that "...seldom is there an occasion of more attraction or greater general interest. Every available space of sitting and standing room was crowded".[53] She starts off her speech by giving a little background about her own life. Sojourner recounts how her mother told her to pray to God that she may have good masters and mistresses. She goes on to retell how her masters were not good to her, about how she was whipped for not understanding English, and how she would question God why he had not made her masters be good to her. Sojourner admits to the audience that she had once hated white people, but she says once she met her final master, Jesus, she was filled with love for everyone. Once enslaved folks were emancipated, she tells the crowd she knew her prayers had been answered. That last part of Sojourner's speech brings in her main focus. Some freed enslaved people were living on government aid at that time, paid for by taxpayers. Sojourner announces that this is not any better for those colored people than it is for the members of her audience. She then proposes that black people are given their own land. Because a portion of the South's population contained rebels that were unhappy with the abolishment of slavery, that region of the United States was not well suited for colored people. She goes on to suggest that colored people be given land out west to build homes and prosper on.

Second Annual Convention of the American Woman Suffrage Association – Boston, 1871: In a brief speech, Truth argued that women's rights were essential, not only to their own well-being, but "for the benefit of the whole creation, not only the women, but all the men on the face of the earth, for they were the mother of them".[54]

Truth dedicated her life to fighting for a more equal society for African Americans and for women, including abolition, voting rights, and property rights. She was at the vanguard of efforts to address intersecting social justice issues. As historian Martha Jones wrote, "[w]hen Black women like Truth spoke of rights, they mixed their ideas with challenges to slavery and to racism. Truth told her own stories, ones that suggested that a women's movement might take another direction, one that championed the broad interests of all humanity."[55]

Truth—along with Stephen Symonds Foster and Abby Kelley Foster, Jonathan Walker, Marius Robinson, and Sallie Holley—reorganized the Michigan Anti-Slavery Society in 1853 in Adrian, Michigan.[56] The state society was founded in 1836 in Ann Arbor, Michigan.[57]

In 1856, Truth bought a neighboring lot in Northampton, but she did not keep the new property for long. On September 3, 1857, she sold all her possessions, new and old, to Daniel Ives and moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, where she rejoined former members of the Millerite movement who had formed the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Antislavery movements had begun early in Michigan and Ohio. Here, she also joined the nucleus of the Michigan abolitionists, the Progressive Friends, some who she had already met at national conventions.[20] From 1857 to 1867 Truth lived in the village of Harmonia, Michigan, a Spiritualist utopia. She then moved into nearby Battle Creek, Michigan, living at her home on 38 College St. until her death in 1883.[58] According to the 1860 census, her household in Harmonia included her daughter, Elizabeth Banks (age 35), and her grandsons James Caldwell (misspelled as "Colvin"; age 16) and Sammy Banks (age 8).[16]

Truth helped recruit black troops for the Union Army during the Civil War. Her grandson, James Caldwell, enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. In 1864, Truth was employed by the National Freedman's Relief Association in Washington, D.C., where she worked diligently to improve conditions for African-Americans. In October of that year, she was invited to the White House by President Abraham Lincoln.[16][59] In 1865, while working at the Freedman's Hospital in Washington, Truth rode in the streetcars to help force their desegregation.[16]

Truth is credited with writing a song, "The Valiant Soldiers", for the 1st Michigan Colored Regiment; it was said to be composed during the war and sung by her in Detroit and Washington, D.C. It is sung to the tune of "John Brown's Body" or "The Battle Hymn of the Republic".[60] Although Truth claimed to have written the words, it has been disputed (see "Marching Song of the First Arkansas").

In 1867, Truth moved from Harmonia to Battle Creek. In 1868, she traveled to western New York and visited with Amy Post, and continued traveling all over the East Coast. At a speaking engagement in Florence, Massachusetts, after she had just returned from a very tiring trip, when Truth was called upon to speak she stood up and said, "Children, I have come here like the rest of you, to hear what I have to say."[61]

In 1870, Truth tried to secure land grants from the federal government to former enslaved people, a project she pursued for seven years without success. While in Washington, D.C., she had a meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant in the White House. In 1872, she returned to Battle Creek, became active in Grant's presidential re-election campaign, and even tried to vote on Election Day, but was turned away at the polling place.[54]

Truth spoke about abolition, women's rights, prison reform, and preached to the Michigan Legislature against capital punishment. Not everyone welcomed her preaching and lectures, but she had many friends and staunch support among many influential people at the time, including Amy Post, Parker Pillsbury, Frances Gage, Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, Laura Smith Haviland, Lucretia Mott, Ellen G. White, and Susan B. Anthony.[61]

Truth was cared for by two of her daughters in the last years of her life. Several days before Sojourner Truth died, a reporter came from the Grand Rapids Eagle to interview her. "Her face was drawn and emaciated and she was apparently suffering great pain. Her eyes were very bright and mind alert although it was difficult for her to talk."[16]

Truth died early in the morning on November 26, 1883, at her Battle Creek home.[62] On November 28, 1883, her funeral was held at the Congregational-Presbyterian Church officiated by its pastor, the Reverend Reed Stuart. Some of the prominent citizens of Battle Creek acted as pall-bearers; nearly one thousand people attended the service. Truth was buried in the city's Oak Hill Cemetery.[63]

Frederick Douglass offered a eulogy for her in Washington, D.C. "Venerable for age, distinguished for insight into human nature, remarkable for independence and courageous self-assertion, devoted to the welfare of her race, she has been for the last forty years an object of respect and admiration to social reformers everywhere."[64][65]

There have been many memorials erected in honor of Sojourner Truth, commemorating her life and work. These include memorial plaques, busts, and full-sized statues.

The first historical marker honoring Truth was established in Battle Creek in 1935, when a stone memorial was placed in Stone History Tower, in Monument Park. The State of Michigan further recognized her legacy by naming highway M-66 in Calhoun County the Sojourner Truth Memorial Highway.[66][67]

1999 marked the estimated bicentennial of Sojourner's birth. To honor the occasion, a larger-than-life sculpture of Sojourner Truth[68] by Tina Allen was added to Monument Park in Battle Creek. The 12-foot tall Sojourner monument is cast in bronze.[69]

In 1981, an Ohio Historical Marker was unveiled on the site of the Universalist "Old Stone" Church in Akron where Sojourner Truth gave her "Ain't I a Woman?" speech on May 29, 1851.[70][71] Sojourner Truth Legacy Plaza, which includes a statue of her by sculptor and Akron native Woodrow Nash, opened in Akron in 2024.[72][73]

In 1862, American sculptor William Wetmore Story completed a marble statue, inspired by Sojourner Truth, named The Libyan Sibyl.[74] The work won an award at the London World Exhibition. The original sculpture was gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York City, by the Erving Wolf Foundation in 1978.

In 1983, a plaque honoring Sojourner Truth was unveiled in front of the historic Ulster County Courthouse in Kingston, New York. The plaque was given by the Sojourner Truth Day Committee to commemorate the centennial of her death.[75]

In 1990, New York Governor Mario Cuomo presented a two-foot statue of Sojourner Truth, made by New York sculptor Ruth Inge Hardison, to Nelson Mandela during his visit to New York City.[76]

In 1998, on the 150th anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention, a life-sized, terracotta statue of Truth by artists A. Lloyd Lillie, Jr., and Victoria Guerina was unveiled at the Women's Rights National Historical Park visitor's center. Although Truth did not attend the convention, the statue marked Truth's famous 1851 speech in Akron, Ohio, and recognized her important role in the fight for women's suffrage.

In 2013, a bronze statue of Truth as an 11-year-old girl was installed at Port Ewen, New York, where Truth lived for several years while still enslaved. The sculpture was created by New Paltz, New York, sculptor Trina Green.[77]

In 2015, the Klyne Esopus Museum installed a historical marker in Ulster Park, New York commemorating Truth's walk to freedom in 1826. She walked about 14 miles from Esopus, up what is now Floyd Ackert Road, to Rifton, New York.[78]

In 2020, a statue was unveiled at the Walkway Over the Hudson park in Highland, New York. It was created by Yonkers sculptor Vinnie Bagwell, commissioned by the New York State Women's Suffrage Commission.[79] The statue includes text, braille, and symbols. The folds of her skirt act as a canvas to depict Sojourner's life experiences, including images of a young enslaved mother comforting her child, a slavery sale sign, images of her abolitionist peers, and a poster for a women's suffrage march.[80][81][82][83]

On August 26, 2020, on the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, a statue honoring Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony was unveiled in Central Park in New York City.[84] The sculpture, entitled "Women's Rights Pioneers Monument", was created by American artist Meredith Bergmann. It is the first sculpture in Central Park to depict historical women. A statue to the fictional character Alice in Wonderland is the only other female figure depicted in the park.[85] Original plans for the memorial included only Stanton and Anthony, but after critics raised objections to the lack of inclusion of women of color, Truth was added to the design.[86][87][88]

On February 28, 2022, New York Governor Kathy Hochul dedicated Sojourner Truth State Park near the site of her birthplace.[89]

In 1999, Sojourner, a Mexican limestone statue of Sojourner Truth by sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, was unveiled in Sacramento, California on the corner of K and 13th Street.[90] It was vandalized in 2013, where it was found smashed into pieces.[91]

A bronze statue by San Diego sculptor Manuelita Brown was dedicated on January 22, 2015, on the campus of the Thurgood Marshall College of Law, of the University of California, San Diego, California. The artist donated the sculpture to the college.[92][93]

In 2002, the Sojourner Truth Memorial statue by Oregon sculptor Thomas "Jay" Warren was installed in Florence, Massachusetts, in a small park located on Pine Street and Park Street, on which she lived for ten years.[94][95]

In 2009, a bust of Sojourner Truth was installed in the U.S. Capitol.[96] The bust was sculpted by noted artist Artis Lane. It is in Emancipation Hall of the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center. With this installation, Truth became the first black woman to be honored with a statue in the Capitol building.[97]

In regard to the magazine Ms., which began in 1972,[98][99] Gloria Steinem has stated, "We were going to call it Sojourner, after Sojourner Truth, but that was perceived as a travel magazine.[100]

Truth was posthumously inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1981.[16] She was also inducted to the Michigan Women's Hall of Fame, in Lansing, Michigan. She was part of the inaugural class of inductees when the museum was established in 1983.[16]

The U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative, 22-cent postage stamp honoring Sojourner Truth in 1986.[16][101] The original artwork was created by Jerry Pinkney, and features a double portrait of Truth. The stamp was part of the Black Heritage series. The first day of issue was February 4, 1986.[102]

Truth was included in a monument of "Michigan Legal Milestones" erected by the State Bar of Michigan in 1987, honoring her historic court case.[103]

The calendar of saints of the Episcopal Church remembers Sojourner Truth annually, together with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Amelia Bloomer and Harriet Ross Tubman, on July 20.[104] The calendar of saints of the Lutheran Church remembers Sojourner Truth together with Harriet Tubman on March 10.[105]

In 1997, The NASA Mars Pathfinder mission's robotic rover was named "Sojourner".[106] The following year, S.T. Writes Home[107] appeared on the web offering "Letters to Mom from Sojourner Truth", in which the Mars Pathfinder Rover at times echoes its namesake.

In 2002, Temple University scholar Molefi Kete Asante published a list of 100 Greatest African Americans, which includes Sojourner Truth.[108]

In 2009 Truth was inducted into the National Abolition Hall of Fame, in Peterboro, New York.

In 2014, the asteroid 249521 Truth was named in her honor.[109]

Truth was included in the Smithsonian Institution's list of the "100 Most Significant Americans", published 2014.[10]

The U.S. Treasury Department announced in 2016 that an image of Sojourner Truth will appear on the back of a newly designed $10 bill along with Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Alice Paul and the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession. Designs for new $5, $10 and $20 bills were originally scheduled to be unveiled in 2020 in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of American women winning the right to vote via the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[110] Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin announced that plans for the $20 redesign, which was to feature Harriet Tubman, have been postponed.

On September 19, 2016, the U.S. Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus announced the name of the last ship of a six unit construction contract as USNS Sojourner Truth (T-AO 210).[111] This ship will be part of the latest John Lewis-class of Fleet Replenishment Oilers named in honor of U.S. civil and human rights heroes currently under construction at General Dynamics NASSCO in San Diego, CA.[112]

A Google Doodle was featured on February 1, 2019, in honor of Sojourner Truth.[113] The doodle was showcased in Canada, United States, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Israel, Ireland and Germany.[114]

For their first match of March 2019, the women of the United States women's national soccer team each wore a jersey with the name of a woman they were honoring on the back; Christen Press chose the name of Sojourner Truth.[115]

Metro-North Railroad named one of its Shoreliner II passenger cars – No.6188 – in honor of Sojourner Truth.[116]

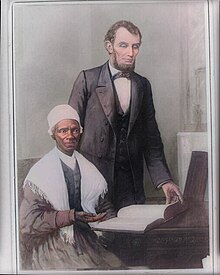

In 1892, Albion artist Frank Courter was commissioned by Frances Titus to paint the meeting between Truth and President Abraham Lincoln that occurred on October 29, 1864.[16]

In 1945, Elizabeth Catlett created a print entitled I'm Sojourner Truth as part of a series honoring the labor of black women. The print is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection.[117] She would later create a full-size statue of Truth, which was displayed in Sacramento, California.

In 1958, African-American artist John Biggers created a mural called the Contribution of Negro Woman to American Life and Education as his doctoral dissertation. It was unveiled at the Blue Triangle Community Center (former YWCA) – Houston, Texas and features Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, and Phillis Wheatley.[118][119]

Inspired by the work of pioneer women's historian Gerda Lerner, feminist artist Judy Chicago (Judith Sylvia Cohen) created a collaborative masterpiece – The Dinner Party, a mixed-media art installation, between the years 1974 and 1979. The Sojourner Truth placesetting is one of 39. The Dinner Party is gifted by the Elizabeth Sackler Foundation to the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum – New York in 2000.[120]

Feminist theorist and author bell hooks titled her first major work after Truth's "Ain't I a Woman?" speech.[121] The book was published in 1981.

African-American composer Gary Powell Nash composed In Memoriam: Sojourner Truth, in 1992.[122]

The Broadway musical The Civil War, which premiered in 1999, includes an abridged version of Truth's "Ain't I a Woman?" speech as a spoken-word segment. On the 1999 cast recording, the track was performed by Maya Angelou.[123]

In 2018, a crocheted mural, Sojourner Truth: Ain't I A Woman?, was hung on display at the Akron Civic Theatre's outer wall at Lock 3 Park in Ohio. It was one of four projects in New York and North Carolina as part of the "Love Across the U.S.A.", spearheaded by fiber artist OLEK.[124]

Starting in 1895, numerous black civic associations adopted the name Sojourner Truth Club or similar titles to honor her.

Examples listing club names, places, years founded:[137]

Fanaticism -.– online edition (pdf format, 9.9 MB

Inductees to the National Women's Hall of Fame | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Enslaved people |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slave owners |

| ||||

| Primary locations | |||||

| Laws |

| ||||

| Events | |||||

| Abolitionists |

| ||||

| Related articles | |||||

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |