Gaius Sallustius Crispus | |

|---|---|

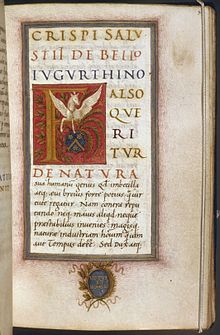

Imaginary portrait of Sallust | |

| Born | 86 BC |

| Died | c. 35 BC |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Occupation(s) | Politician and soldier |

| Office |

|

| Relatives | Gaius Sallustius Passienus Crispus (great-nephew and adopted son) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Caesarian |

| Rank | |

| Wars | Caesar's civil war (49–44 BC) |

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (/ˈsæləst/, SAL-əst; 86 – c. 35 BC),[1] was a historian and politician of the Roman Republic from a plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became a partisan of Julius Caesar (100 to 44 BC), circa 50s BC. He is the earliest known Latin-language Roman historian with surviving works to his name, of which Conspiracy of Catiline on the eponymous conspiracy, The Jugurthine War on the eponymous war, and the Histories (of which only fragments survive) remain extant. As a writer, Sallust was primarily influenced by the works of the 5th-century BC Greek historian Thucydides. During his political career he amassed great and ill-gotten wealth from his governorship of Africa.[2]

Sallust was probably born in Amiternum in Central Italy,[3][4][5] though Eduard Schwartz takes the view that Sallust's birthplace was Rome.[6] His birth date is calculated from the report of Jerome's Chronicon.[7] But Ronald Syme suggests that Jerome's date has to be adjusted because of his carelessness,[7] and suggests 87 BC as a more correct date.[7] However, Sallust's birth is widely dated at 86 BC,[4][8][9] and the Kleine Pauly Encyclopedia takes 1 October 86 BC as the birthdate.[10] Michael Grant cautiously offers 80s BC.[5]

There is no information about Sallust's parents or family,[11] except for Tacitus' mention of his sister.[12] The Sallustii were a provincial noble family of Sabine origin.[4][5][13] They belonged to the equestrian order and had full Roman citizenship.[4] During the Social War Sallust's parents hid in Rome, because Amiternum was under threat of siege by rebelling Italic tribes.[14] Because of this Sallust could have been raised in Rome.[11] He received a very good education.[4]

After an ill-spent youth, Sallust entered public life and may have won election as quaestor in 55 BC.[15] However, the evidence is unclear; some scholars suggest he never held the post.[5][16][17] The "earliest certain information" on his career is his terms as plebeian tribune in 52 BC, the year in which the followers of Milo killed Clodius. During his year, Sallust supported the prosecution of Milo.[18] He also organised "ferocious street demonstrations" to exert public pressure on Cicero, intimidating him into "giving a substandard performance",[19] seeing Milo leave the city into exile. In this year, he, with the other ten tribunes, all supported a law to permit Caesar to stand for a second consulship in absentia.[20]

Syme suggests that Sallust, because of his position in Milo's trial, did not originally support Caesar.[21] According to one inscription, some Sallustius (with unclear praenomen) was a proquaestor in Syria in 50 BC under Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus.[22] Mommsen identified this Sallustius with Sallust the historian, but Broughton argued that Sallust the historian would not have been an assistant to Caesar's adversary or, as an ex-plebeian tribune, have taken the lowly title legatus pro quaestore.[23]

Sallust's political affiliation is unclear in this early period,[24] but after he was expelled from the senate in 50 BC by Appius Claudius Pulcher (then serving as censor), he joined Caesar.[25] He was removed on grounds of immorality, but this was likely a pretext for his opposition to Milo during his tribunate.[26][25]

|

Further information: Caesar's civil war |

During the civil war from 49 to 45 BC, Sallust was a Caesarian partisan, but his role was not significant; his name is not mentioned in the dictator's Commentarii de Bello Civili.[27] Plutarch reported that Sallust dined with Caesar, Hirtius, Oppius, Balbus and Sulpicius Rufus on the night after Caesar's crossing the Rubicon into Italy in early January.[28] In 49 BC, Sallust was moved to Illyricum and probably commanded at least one legion there after the failure of Publius Cornelius Dolabella and Gaius Antonius.[10][27] This campaign was unsuccessful.[27] In 48 BC, he was probably made quaestor by Caesar, automatically restoring his seat in the senate.[10][29] In late summer 47 BC, a group of soldiers rebelled near Rome, demanding their discharge and payment for service. Sallust, as praetor designatus and serving as one of Caesar's legates,[30] with several other senators, was sent to persuade the soldiers to abstain, but the rebels killed two senators, and Sallust narrowly escaped death.[19]

In 46 BC, he served as a praetor[31] and accompanied Caesar in his African campaign, which ended in another defeat of the remaining Pompeians at Thapsus. Sallust did not participate in military operations directly, but he commanded several ships and organized supply through the Kerkennah Islands. As a reward for his services, Sallust was appointed proconsular governor of Africa Nova, either from 46–45 or for early 44 BC.[32] It is not clear why: Sallust was not a skilled general; the province was militarily significant. Moreover, his successors as governor were experienced military men. However, Sallust successfully managed the organization of supply and transportation, and these qualities could have determined Caesar's choice.[33] As governor he was so corrupt and avaricious that – on his return in late 45 or early 44 BC[34] – only Caesar's dictatorial influence enabled him to escape conviction on charges of corruption and extortion.[35] On his return to Rome he purchased and began laying out in great splendour the famous gardens on the Quirinal known as the Gardens of Sallust (Latin: Horti Sallustiani), which were later inherited by the emperors.

Due to those charges and without prospects for advancement, he devoted himself to writing history,[25] presenting his historical writings as an extension of public life to record achievements for future generations.[35] His political life influenced his histories, which produced in him a "deep bitterness toward the elite", with "few heroes in his surviving writings".[36] He also further developed his gardens, upon which he spent much of his accumulated wealth. According to Jerome, Sallust later became the second husband of Cicero's ex-wife Terentia.[37] However, prominent scholars of Roman prosopography such as Ronald Syme believe this is a legend.[38] According to Procopius, when Alaric's invading army entered Rome they burned Sallust's house.[39]

Sallust's monographs of the Catiline conspiracy (De coniuratione Catilinae or Bellum Catilinae) and the Jugurthine War (Bellum Jugurthinum) have come down to us complete, together with fragments of his larger and most important work (Historiae), a history of Rome from 78 to 67 BC.[40]

His brief monographs – his work on Catiline, for example, is shorter than the shortest of Livy's volumes – were the first books of their form attested at Rome.[41]

|

Main article: Bellum Catilinae |

The monograph was probably written c. 42 BC.[25] Some historians, however, give it an earlier date of composition, perhaps as early at 50 BC as an unpublished pamphlet which was reworked and published after the civil wars.[42] It shows no traces of personal recollections on the conspiracy, perhaps indicating the Sallust was out of the city on military service at the time.[43] It may have been written as "a plea for common sense" during the proscriptions of the Second Triumvirate, with its depiction of Caesar opposing the death penalty contrasting with the then-current slaughter.[44]

It is Sallust's first published work, detailing the attempt by Lucius Sergius Catilina to overthrow the Roman Republic in 63 BC. Sallust presents Catiline as a deliberate foe of law, order and morality, and does not give a comprehensive explanation of his views and intentions (Catiline had supported the party of Sulla, whom Sallust had opposed). Theodor Mommsen suggested that Sallust particularly wished to clear his patron (Caesar) of all complicity in the conspiracy.[citation needed]

In writing about the conspiracy of Catiline, Sallust's tone, style, and descriptions of aristocratic behaviour illustrate "the political and moral decline of Rome, begun after the fall of Carthage, quickening after Sulla's dictatorship, and spreading from the dissolute nobility to infect all Roman politics".[25] While he inveighs against Catiline's depraved character and vicious actions, he does not fail to state that the man had many noble traits. In particular, Sallust shows Catiline as deeply courageous in his final battle.[citation needed] He presents a narrative condemning the conspirators without doubt, likely relying on Cicero's De consulatu suo (lit. 'On his [Cicero's] consulship') for details of the conspiracy;[45] his narrative focused, however, on Caesar and Cato the Younger, who are held up as "two examples of virtus ('excellence')" with long speeches describing a debate on the punishment of the conspirators in the last section.[46][47]

|

Main article: Bellum Jugurthinum |

Sallust's Jugurthine War (Latin: Bellum Jugurthinum) is a monograph on the war against Jugurtha in Numidia from 112 to 106 BC. It was written c. 41–40 BC and again emphasised moral decline.[48] Sallust likely relied on a general annalistic history of the time, as well as the autobiographies of Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, Publius Rutilius Rufus, and Sulla.[48]

Its true value lies in the introduction of Marius and Sulla to the Roman political scene and the beginning of their rivalry. Sallust's time as governor of Africa Nova ought to have let the author develop a solid geographical and ethnographical background to the war; however, this is not evident in the monograph, despite a diversion on the subject, because Sallust's priority in the Jugurthine War, as with the Catiline Conspiracy, is to use history as a vehicle for his judgement on the slow destruction of Roman morality and politics.[citation needed]

|

See also: Epistula Mithridatis |

His last work, Historiae, covered events from 78 BC; none of it survives except a fragment of book 5, concerning the year 67 BC.[48] From the extant fragments, he seemed to again emphasize moral decline after Sulla; he "was not generous to Pompey".[48] Historians regret the loss of the work, as it must have thrown much light on a very eventful period, embracing the war against Sertorius (died 72 BC), the campaigns of Lucullus against Mithradates VI of Pontus (75-66 BC), and the victories of Pompey in the East (66–62 BC).[citation needed]

Two letters (Duae epistolae de republica ordinanda), letters of political counsel and advice addressed to Caesar, and an attack upon Cicero (Invectiva or Declamatio in Ciceronem), frequently attributed to Sallust, are thought by modern scholars to have come from the pen of a rhetorician of the first century AD, along with a counter-invective attributed to Cicero. At one time Marcus Porcius Latro was considered a candidate for the authorship of the pseudo-Sallustian corpus, but this view is no longer commonly held.[49]

The core theme of his work was decline, though his treatment of Roman politics was "often crude", with a historical philosophy influenced by Thucydides.[51] In this, he felt a "pervasive pessimism" with decline that was "both dreadful and inevitable", a consequence of political and moral corruption itself caused by Rome's immense power:[47] he traced the civil war to the influx of wealth from conquest and the absence of serious foreign threats to hone and exercise Roman virtue at arms.[52] For Sallust, the defining moments of the late republic were the destruction of Rome's old foe, Carthage, in 146 BC and the influx of wealth from the east after Sulla's First Mithridatic War.[53] At the same time, however, he conveyed a "starry-eyed and romantic picture" of the republic before 146 BC, with this period described in terms of "implausibly untrammelled virtue" that romanticised the distant past.[54]

The style of works written by Sallust was well known in Rome. It differs from the writings of his contemporaries — Caesar and especially Cicero. It is characterized by brevity and by the use of rare words and turns of phrase. As a result, his works are very far from the conversational Latin of his time.[55]

He employed archaic words: according to Suetonius, Lucius Ateius Praetextatus (Philologus) helped Sallust to collect them.[56] Ronald Syme suggests that Sallust's choice of style and even particular words was influenced by his antipathy to Cicero, his rival, but also one of the trendsetters in Latin literature in the first century BC.[57] More recent scholars agree, describing Sallust's style as "anti-Ciceronian", eschewing the harmonious structure of Cicero's sentences for short and abrupt descriptions.[58] "The Conspiracy of Catiline" reflects many features of style that were developed in his later works.[59]

Sallust avoids common words from public speeches of contemporary Roman political orators, such as honestas, humanitas, consensus.[60] In several cases he uses rare forms of well-known words: for example, lubido instead of libido, maxumum instead of maximum, the conjunction quo in place of more common ut. He also uses the less common endings -ere instead of common -erunt in the third person plural in the perfect indicative, and -is instead of -es in the accusative plural for third declension (masculine or feminine) adjectives and nouns. Some words used by Sallust (for example, antecapere, portatio, incruentus, incelebratus, incuriosus), are not known in other writings before him. They are believed to be either neologisms or intentional revivals of archaic words.[61] Sallust also often uses antithesis, alliterations and chiasmus.[62]

This style itself called for "a 'return to values'" which was "made to recall the austere life of the idealised ancient Roman", with archaisms and abrupt writing contrasted against Cicero's "adornment" as present decadence was contrasted with ancient virtues.[52]

On the whole, antiquity looked favourably on Sallust as a historian. Tacitus speaks highly of him.[63] Quintilian called him the "Roman Thucydides".[41] Martial joins the praise: "Sallust, according to the judgment of the learned, will rank as the prince of Roman historiographers".[64]

In late antiquity, he was highly praised by Jerome as "very reliable"; his monographs also entered the corpus of standard education in Latin, with Virgil, Cicero, and Terence (covering history, the epic, oratory, and comedy, respectively).[65]

In the thirteenth century Sallust's passage on the expansion of the Roman Republic (Cat. 7) was cited and interpreted by theologian Thomas Aquinas and scholar Brunetto Latini.[66] During the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance, Sallust's works began to influence political thought in Italy. Among many scholars and historians interested in Sallust, the most notable are Leonardo Bruni, Coluccio Salutati and Niccolò Machiavelli.[67] Among his admirers in England in the early modern period were Thomas More, Alexander Barclay and Thomas Elyot.[68] Justus Lipsius marked Sallust as the second most notable Roman historian after Tacitus.[69]

Historians since the 19th century also have negatively noted Sallust's bias and partisanship in his histories, not to mention some errors in geography and dating. Also importantly, much of Sallust's anti-corruption moralising is "blunted by his sanctimonious tone and by ancient accusations of corruption, which have made him out to be a remarkable hypocrite".[70]

Modern views on the period which Sallust documented reject moral failure as a cause of the republic's collapse and believe that "social conflicts are insufficient to account for the political implosion".[71] The core narrative of moral decline prevalent in Sallust's works, is now criticised as crowding out his own examination of the structural and socio-economic factors that brought about the crisis of the republic while also manipulating historical facts to make them fit his moralistic thesis; he, however, is credited as "a clear-sighted and impartial interpreter of his own age".[72]

His focus on moralising also misrepresents and over-simplifies the state of Roman politics. For example, Mackay 2009, pp. 84, 89:

Sallust paints a picture that is unsatisfactory in a number of ways. He has great interest in moralising, and for this reason, he tends to paint an exaggerated picture of the senate's faults... he analyses events in terms of a simplistic opposition between the self-interest of Roman politicians and the "public good" that shows little understanding of how the Roman political system actually functioned...[73] The reality was more complicated than Sallust's simplistic moralising would suggest.[74]

Quotations and commentaries "attest to the high status of Sallust's work in the first and second centuries CE".[75] Among those who borrowed information from his works were Silius Italicus, Lucan, Plutarch, and Ammianus Marcellinus.[76][77] Fronto used ancient words collected by Sallust to provide "archaic coloring" for his works.[78] In the second century AD, Zenobius translated his works into Ancient Greek.[76]

Other opinions were also present. For example, Gaius Asinius Pollio criticized Sallust's addiction to archaic words and his unusual grammatical features.[79] Aulus Gellius saved Pollio's unfavorable statement about Sallust's style via quote. According to him, Sallust once used the word transgressus meaning generally "passage [by foot]" for a platoon which crossed the sea (the usual word for this type of crossing was transfretatio).[80] Though Quintilian has a generally favorable opinion of Sallust, he disparages several features of his style:

For though a diffuse irrelevance is tedious, the omission of what is necessary is positively dangerous. We must therefore avoid even the famous terseness of Sallust (though in his case of course it is a merit), and shun all abruptness of speech, since a style which presents no difficulty to a leisurely reader, flies past a hearer and will not stay to be looked at again.[81]

His works were also extensively quoted in Augustine of Hippo's City of God; the works themselves also show up in manuscripts all over the post-Roman period and circulated in Carolingian libraries.[75] In the Middle Ages, Sallust's works were often used in schools to teach Latin. His brief style influenced, among others, Widukind of Corvey and Wipo of Burgundy.[82]

Petrarch also praised Sallust highly, though he primarily appreciated his style and moralization.[83] During the French Wars of Religion, De coniuratione Catilinae became widely known as a tutorial on disclosing conspiracies.[84]

Friedrich Nietzsche credits Sallust in Twilight of the Idols (1889) for his epigrammatic style: "My sense of style, for the epigram as a style, was awakened almost instantly when I came into contact with Sallust" and praises him for being "condensed, severe, with as much substance as possible in the background, and with cold but roguish hostility towards all 'beautiful words' and 'beautiful feelings'".[85]

Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen's first play Catiline (c. 1849) was based on Sallust's story.[82]

Several manuscripts of his works survived due to his popularity in antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Manuscripts of his writings are usually divided into two groups: mutili (mutilated) and integri (whole; undamaged). The classification is based on the existence of the lacuna (gap) between 103.2 and 112.3 of the Jugurthine War. The lacuna exists in the mutili scrolls, while integri manuscripts have the text there. The most ancient scrolls which survive are the Codex Parisinus 16024 and Codex Parisinus 16025, known as "P" and "A" respectively. They were created in the ninth century, and both belong to the mutili group.[86] Both these scrolls include only Catiline and Jugurtha, while some other mutili manuscripts also include Invective and Cicero's response.[87] The oldest integri scrolls were created in the eleventh century AD.[88] The probability that all these scrolls came from one or more ancient manuscripts is debated.[89]

There is also a unique scroll Codex Vaticanus 3864, known as "V". It includes only speeches and letters from Catiline, Jugurtha and Histories.[86] The creator of this manuscript changed the original word order and replaced archaisms with more familiar words.[86] The "V" scroll also includes two anonymous letters to Caesar probably from Sallust,[86] but their authenticity is debated.

Several fragments of Sallust's works survived in papyri of the second to fourth centuries AD. Many ancient authors cited Sallust, and sometimes their citations of Histories are the only source for reconstruction of this work. But the significance of these citations for the reconstruction is uncertain; because occasionally the authors cited Sallust from memory, some distortions were possible.[90]

((cite book)): CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link)