| The Shawshank Redemption | |

|---|---|

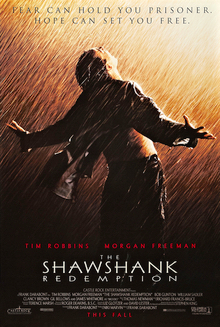

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Frank Darabont |

| Screenplay by | Frank Darabont |

| Based on | Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption by Stephen King |

| Produced by | Niki Marvin |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Roger Deakins |

| Edited by | Richard Francis-Bruce |

| Music by | Thomas Newman |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 142 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[2] |

| Box office | $73.3 million |

The Shawshank Redemption is a 1994 American prison drama film written and directed by Frank Darabont, based on the 1982 Stephen King novella Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption. The film tells the story of banker Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins), who is sentenced to life in Shawshank State Penitentiary for the murders of his wife and her lover, despite his claims of innocence. Over the following two decades, he befriends a fellow prisoner, contraband smuggler Ellis "Red" Redding (Morgan Freeman), and becomes instrumental in a money laundering operation led by the prison warden Samuel Norton (Bob Gunton). William Sadler, Clancy Brown, Gil Bellows, and James Whitmore appear in supporting roles.

Darabont purchased the film rights to King's story in 1987, but development did not begin until five years later, when he wrote the script over an eight-week period. Two weeks after submitting his script to Castle Rock Entertainment, Darabont secured a $25 million budget to produce The Shawshank Redemption, which started pre-production in January 1993. While the film is set in Maine, principal photography took place from June to August 1993 almost entirely in Mansfield, Ohio, with the Ohio State Reformatory serving as the eponymous penitentiary. The project attracted many stars for the role of Andy, including Tom Hanks, Tom Cruise, and Kevin Costner. Thomas Newman provided the film's score.

While The Shawshank Redemption received critical acclaim upon its release—particularly for its story, the performances of Robbins and Freeman, Newman's score, Darabont's direction and screenplay and Roger Deakins' cinematography—the film was a box-office disappointment, earning only $16 million during its initial theatrical run. Many reasons were cited for its failure at the time, including competition from the films Pulp Fiction and Forrest Gump, the general unpopularity of prison films, its lack of female characters, and even the title, which was considered to be confusing for audiences. It went on to receive multiple award nominations, including seven Academy Award nominations, and a theatrical re-release that, combined with international takings, increased the film's box-office gross to $73.3 million.

Over 320,000 VHS rental copies were shipped throughout the United States, and on the strength of its award nominations and word of mouth, it became the top video rental of 1995. The broadcast rights were acquired following the purchase of Castle Rock Entertainment by Turner Broadcasting System, and it was shown regularly on the TNT network starting in 1997, further increasing its popularity. Decades after its release, the film is still broadcast regularly, and is popular in several countries, with audience members and celebrities citing it as a source of inspiration or naming it a favorite in various surveys, leading to its recognition as one of the most "beloved" films ever made. In 2015, the United States Library of Congress selected the film for preservation in the National Film Registry, finding it "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

[edit]In 1947, Portland, Maine banker Andy Dufresne arrives at Shawshank State Prison to serve two consecutive life sentences for murdering his wife and her lover. He is befriended by Ellis "Red" Redding, a contraband smuggler serving a life sentence, who procures a rock hammer and a large poster of Rita Hayworth for Andy. Assigned to work in the prison laundry, Andy is frequently raped by "the Sisters" prison gang and their leader, Bogs Diamond.

In 1949, Andy overhears the captain of the guards, Byron Hadley, complaining about being taxed on an inheritance and offers to help him shelter the money legally. After an assault by the Sisters nearly kills Andy, Hadley beats and cripples Bogs, who is subsequently transferred to a minimum security hospital; Andy is not attacked again. Warden Samuel Norton meets Andy and reassigns him to the decrepit prison library to assist elderly inmate Brooks Hatlen, a front to use Andy's financial expertise to manage financial matters for other prison staff and the warden himself. Andy begins writing weekly letters to the state legislature requesting funds to improve the library.

Brooks is paroled in 1954 after serving 50 years, but cannot adjust to the outside world and eventually hangs himself. The legislature sends a library donation that includes a recording of The Marriage of Figaro; Andy plays an excerpt over the public address system and is punished with solitary confinement. After his release from solitary, Andy explains to a dismissive Red that hope is what gets him through his sentence. In 1963, Norton begins exploiting prison labor for public works, profiting by undercutting skilled labor costs and receiving bribes. Andy launders the money using the alias "Randall Stephens."

In 1965, Andy and Red befriend Tommy Williams, a young prisoner incarcerated for burglary. A year later, Andy helps him pass his General Educational Development (GED) exam. Tommy reveals to Red and Andy that his cellmate at another prison had claimed responsibility for the murders for which Andy was convicted. Andy brings the information to Norton, who refuses to listen. When Andy mentions the money laundering, Norton sends Andy to solitary confinement and has Hadley fatally shoot Tommy under the guise of an escape attempt. After Andy refuses to continue the money laundering, Norton threatens to destroy the library, remove Andy's protection by the guards, and move him to worse conditions.

Andy is released from solitary confinement after two months and tells a skeptical Red that he dreams of living in Zihuatanejo, a Mexican town on the Pacific coast. He asks Red to promise, once he is released, to travel to a specific hayfield near Buxton and recover a package that Andy buried there. Red worries about Andy's mental well-being, especially when he learns Andy asked a fellow inmate for a rope.

At the next day's roll call, the guards find Andy's cell empty. An irate Norton throws a rock at the poster hanging on the cell wall, and finds behind it a tunnel that Andy had dug with his rock hammer over nearly two decades. The previous night, Andy used the rope to escape through the tunnel and prison sewage pipe, taking Norton's suit, shoes, and ledger, containing evidence of the money laundering and corruption at Shawshank. While guards search for him, Andy poses as Randall Stephens and withdraws over $370,000[a] of the laundered money from several banks, and mails the ledger to a local newspaper. State police arrive at Shawshank and take Hadley into custody, while Norton commits suicide to avoid arrest.

The following year, Red is paroled after serving 40 years but struggles to adapt to life outside prison and fears that he never will. Remembering his promise to Andy, he visits Buxton and finds a cache containing money and a letter asking him to come to Zihuatanejo. Red violates his parole by traveling to Fort Hancock, Texas and crossing the border into Mexico, admitting that he finally feels hope. He finds Andy on a Zihuatanejo beach, and the reunited friends happily embrace.

Cast

[edit]- Tim Robbins as Andy Dufresne: A banker sentenced to life in prison in 1947 for the murder of his wife and her lover[3]

- Morgan Freeman as Ellis Boyd "Red" Redding: A prison contraband smuggler who befriends Andy[4][5]

- Bob Gunton as Samuel Norton: The pious and cruel warden of Shawshank penitentiary[3]

- William Sadler as Heywood: A member of Red's gang of long-serving convicts[4][6]

- Clancy Brown as Byron Hadley: The brutal captain of the prison guards[7][8]

- Gil Bellows as Tommy Williams: A young convict imprisoned for burglary in 1965[4][9]

- James Whitmore as Brooks Hatlen: The elderly prison librarian, imprisoned at Shawshank for over five decades[10]

The cast also includes Mark Rolston as Bogs Diamond, the head of "the Sisters" gang and a prison rapist;[11] Jeffrey DeMunn as the prosecuting attorney in Dufresne's trial; Alfonso Freeman as Fresh Fish Con; Ned Bellamy and Don McManus as, respectively, prison guards Youngblood and Wiley; and Dion Anderson as Head Bull Haig.[4] Renee Blaine portrays Andy's wife, and Scott Mann portrays her golf-instructor lover Glenn Quentin.[12] Frank Medrano plays Fat Ass, one of Andy's fellow new inmates who is beaten to death by Hadley,[4][13] and Bill Bolender plays Elmo Blatch, a convict who is implied to be responsible for the crimes for which Andy is convicted.[14] James Kisicki and Claire Slemmer portray the Maine National Bank manager and a teller, respectively.[15][16]

Analysis

[edit]The film has been interpreted as being grounded in Christian mysticism.[17] Andy is offered as a messianic, Christ-like figure, with Red describing him early in the film as having an aura that engulfs and protects him from Shawshank.[18] The scene in which Andy and several inmates tar the prison roof can be seen as a recreation of the Last Supper, with Andy obtaining beer/wine for the twelve inmates/disciples as Freeman describes them as the "lords of all creation" invoking Jesus' blessing.[19] Director Frank Darabont responded that this was not his deliberate intention,[20] but he wanted people to find their own meaning in the film.[21] The discovery of The Marriage of Figaro record is described in the screenplay as akin to finding the Holy Grail, bringing the prisoners to a halt, and causing the sick to rise up in their beds.[22]

Early in the film, Warden Norton quotes Jesus Christ to describe himself to Andy, saying, "I am the light of the world", declaring himself Andy's savior, but this description can also reference Lucifer, the bearer of light.[23] Indeed, the warden does not enforce the general rule of law, but chooses to enforce his own rules and punishments as he sees fit, becoming a law unto himself, like the behavior of Satan.[3] The warden has also been compared to former United States President Richard Nixon. Norton's appearance and public addresses can be seen to mirror Nixon's. Similarly, Norton projects an image of a holy man, speaking down sanctimoniously to the servile masses while running corrupt scams, like those of which Nixon was accused.[24]

Zihuatanejo has been interpreted as an analog for heaven or paradise.[25] In the film, Andy describes it as a place with no memory, offering absolution from his sins by forgetting about them or allowing them to be washed away by the Pacific Ocean, whose name means "peaceful". The possibility of escaping to Zihuatanejo is only raised after Andy admits that he feels responsible for his wife's death.[25] Similarly, Red's freedom is only earned once he accepts he cannot save himself or atone for his sins. Freeman has described Red's story as one of salvation as he is not innocent of his crimes, unlike Andy who finds redemption.[26]

While some Christian viewers interpret Zihuatanejo as heaven, film critic Mark Kermode wrote that it can also be interpreted as a Nietzschean form of guiltlessness achieved outside traditional notions of good and evil, where the amnesia offered is the destruction rather than forgiveness of sin, meaning Andy's aim is secular and atheistic. Just as Andy can be interpreted as a Christ-like figure, he can be seen as a Zarathustra-like prophet offering escape through education and the experience of freedom.[25] Film critic Roger Ebert argued that The Shawshank Redemption is an allegory for maintaining one's feeling of self-worth when placed in a hopeless position. Andy's integrity is an important theme in the story line, especially in prison, where integrity is lacking.[27]

Robbins himself believes that the concept of Zihuatanejo resonates with audiences because it represents a form of escape that can be achieved after surviving for many years within whatever "jail" someone finds themselves in, whether a bad relationship, job, or environment. Robbins said that it is important that such a place exists for us.[28] Isaac M. Morehouse suggests that the film provides a great illustration of how characters can be free, even in prison, or imprisoned, even in freedom, based on their outlooks on life.[29] Philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre described freedom as an ongoing project that requires attention and resilience, without which a person begins to be defined by others or institutions, mirroring Red's belief that inmates become dependent on the prison to define their lives. Andy displays resilience through rebellion, by playing music over the prison loudspeaker, and refusing to continue with the money-laundering scam.[3]

Many elements can be considered as tributes to the power of cinema. In the prison theater, the inmates watch the film Gilda (1946), but this scene was originally intended to feature The Lost Weekend (1945). The interchangeability of the films used in the prison theater suggests that it is the cinematic experience and not the subject that is key to the scene, allowing the men to escape the reality of their situation.[30] Immediately following this scene, Andy is assaulted by the Sisters in the projector room and uses a film reel to help fight them off.[31] At the end of the film, Andy passes through a hole in his cell hidden by a movie poster to escape both his cell and ultimately Shawshank.[32]

Andy and Red's relationship has been described as a nonsexual story between two men,[33] that few other films offer, as the friendship is not built on conducting a caper, car chases, or developing a relationship with women.[34] Philosopher Alexander Hooke argued that Andy and Red's true freedom is their friendship, being able to share joy and humor with each other.[3]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Frank Darabont first collaborated with author Stephen King in 1983 on the short film adaptation of "The Woman in the Room", buying the rights from him for $1—a Dollar Deal that King used to help new directors build a résumé by adapting his short stories.[8] After receiving his first screenwriting credit in 1987 for A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, Darabont returned to King with $5,000[35] to purchase the rights to adapt Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, a 96-page novella from King's 1982 collection Different Seasons, written to explore genres other than the horror stories for which he was commonly known.[36] Although King did not understand how the story, largely focused on Red contemplating his fellow prisoner Andy, could be turned into a feature film, Darabont believed it was "obvious".[8] King never cashed the $5,000 check from Darabont; he later framed it and returned it to Darabont accompanied by a note which read: "In case you ever need bail money. Love, Steve."[37]

Five years later, Darabont wrote the script over an eight-week period. He expanded on elements of King's story. Brooks, who in the novella is a minor character who dies in a retirement home, became a tragic character who eventually hanged himself. Tommy, who in the novella trades his evidence exonerating Andy for transfer to a nicer prison, in the screenplay is murdered on the orders of Warden Norton, who is a composite of several warden characters in King's story.[8] Darabont opted to create a single warden character to serve as the primary antagonist.[38] Among his inspirations, Darabont listed the works of director Frank Capra, including Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and It's a Wonderful Life (1946), describing them as tall tales; Darabont likened The Shawshank Redemption to a tall tale more than a prison movie.[39] He also cited Goodfellas (1990) as an inspiration on the use of dialogue to illustrate the passage of time in the script, and the prison drama Birdman of Alcatraz (1962) directed by John Frankenheimer.[40] While later scouting filming locations, Darabont happened upon Frankenheimer who was scouting for his own prison-set project Against the Wall. Darabont recalled that Frankenheimer took time out from his scouting to provide Darabont with encouragement and advice.[41]

At the time, prison-based films were not considered likely box-office successes, but Darabont's script was read by then-Castle Rock Entertainment producer Liz Glotzer, whose interest in prison stories and reaction to the script, led her to threaten to quit if Castle Rock Entertainment did not produce The Shawshank Redemption.[8] Director and Castle Rock Entertainment co-founder Rob Reiner also liked the script. He offered Darabont between $2.4 million[42] and $3 million to allow him to direct it himself.[8] Reiner, who had previously adapted King's 1982 novella The Body into the 1986 film Stand by Me, planned to cast Tom Cruise as Andy and Harrison Ford as Red.[8][43]

Castle Rock Entertainment offered to finance any other film Darabont wanted to develop. Darabont seriously considered the offer, citing growing up poor in Los Angeles, believing it would elevate his standing in the industry, and that Castle Rock Entertainment could have contractually fired him and given the film to Reiner anyway, but he chose to remain the director, saying in a 2014 Variety interview, "you can continue to defer your dreams in exchange for money and, you know, die without ever having done the thing you set out to do".[8] Reiner served as Darabont's mentor on the project, instead.[8] Within two weeks of showing the script to Castle Rock Entertainment, Darabont had a $25 million budget to make his film[2] (taking a $750,000 screenwriting and directing salary plus a percentage of the net profits),[42] and pre-production began in January 1993.[39][b]

Casting

[edit]

Morgan Freeman was cast at the suggestion of producer Liz Glotzer, who ignored the novella's character description of a white Irishman, nicknamed "Red". Freeman's character alludes to the choice when queried by Andy on why he is called Red, replying "Maybe it's because I'm Irish."[40] Freeman opted not to research his role, saying "acting the part of someone who's incarcerated doesn't require any specific knowledge of incarceration ... because men don't change. Once you're in that situation, you just toe whatever line you have to toe."[2] Darabont was already aware of Freeman from his minor role in another prison drama, Brubaker (1980), while Tim Robbins had been excited to work alongside Freeman, having grown up watching him in The Electric Company children's television show.[41]

Darabont looked initially at some of his favorite actors, such as Gene Hackman and Robert Duvall, for the role of Andy Dufresne, but they were unavailable;[40] Clint Eastwood and Paul Newman were also considered.[44] Tom Cruise, Tom Hanks, and Kevin Costner were offered, and passed on the role[8]—Hanks due to his starring role in Forrest Gump,[40] and Costner because he had the lead in Waterworld.[45] Johnny Depp, Nicolas Cage, and Charlie Sheen were also considered for the role at different stages.[45] Cruise attended table readings of the script, but declined to work for the inexperienced Darabont.[8] Darabont said he cast Robbins after seeing his performance in the 1990 psychological horror Jacob's Ladder.[46] When Robbins was cast, he insisted that Darabont use experienced cinematographer Roger Deakins, who had worked with him on The Hudsucker Proxy.[8] To prepare for the role, Robbins observed caged animals at a zoo, spent an afternoon in solitary confinement, spoke with prisoners and guards,[33] and had his arms and legs shackled for a few hours.[2]

Cast initially as young convict Tommy, Brad Pitt dropped out following his success in Thelma & Louise, and the role went to a debuting Gil Bellows.[2][8] James Gandolfini passed on portraying prison rapist Bogs.[8] Bob Gunton was filming Demolition Man (1993) when he went to audition for the role of Warden Norton. To convince the studio that Gunton was right for the part, Darabont and producer Niki Marvin arranged for him to record a screen test on a day off from Demolition Man. They had a wig made for him as his head was shaved for his Demolition Man role. Gunton wanted to portray Norton with hair as this could then be grayed to convey his on-screen aging as the film progressed. Gunton performed his screen test with Robbins, which was filmed by Deakins. After being confirmed for the role, he used the wig in the film's early scenes until his hair regrew. Gunton said that Marvin and Darabont saw that he understood the character, which went in his favor, as did the fact his height was similar to Robbins', allowing Andy to believably use the warden's suit.[38]

Portraying the head guard Byron Hadley, Clancy Brown was given the opportunity to speak with former guards by the production's liaison officer but declined, believing it would not be a good thing to say that his brutal character was in any way inspired by Ohio state correctional officers.[47] William Sadler, who portrays Heywood, said that Darabont had approached him in 1989 on the set of the Tales from the Crypt television series, where he was a writer, about starring in the adaptation he was intending to make.[48] Freeman's son Alfonso has a cameo as a young Red in mug shot photos,[40] and as a prisoner shouting "fresh fish" as Andy arrives at Shawshank.[49] Among the extras used in the film were the former warden and former inmates of the reformatory, and active guards from a nearby incarceration facility.[2][50] The novella's original title attracted several people to audition for the nonexistent role of Rita Hayworth, including a man in drag clothing.[42]

Filming

[edit]

On a $25 million budget,[51] principal photography took place over three months[8] between June and August 1993.[52][53] Filming regularly required up to 18-hour workdays, six days a week.[8] Freeman described filming as tense, saying, "Most of the time, the tension was between the cast and director. I remember having a bad moment with the director, had a few of those." Freeman referred to Darabont's requiring multiple takes of scenes, which he considered had no discernible differences. For example, the scene where Andy first approaches Red to procure a rock hammer took nine hours to film and featured Freeman throwing and catching a baseball with another inmate throughout it. The number of takes that were shot resulted in Freeman turning up to filming the following day with his arm in a sling. Freeman sometimes simply refused to do the additional takes. Robbins said that the long days were difficult. Darabont felt that making the film taught him a lot, "A director really needs to have an internal barometer to measure what any given actor needs."[8] He found his most frequent struggles were with Deakins. Darabont favored more scenic shots, while Deakins felt that not showing the outside of the prison added a sense of claustrophobia, and it meant that when a wide scenic shot was used, it had more impact.[2]

Marvin spent five months scouting prisons across the United States and Canada, looking for a site that had a timeless aesthetic, and was completely abandoned, hoping to avoid the complexity of filming the required footage, for hours each day, in an active prison with the security difficulties that would entail.[54] Marvin eventually chose the Ohio State Reformatory in Mansfield, Ohio, to serve as the fictional Shawshank State Penitentiary in Maine, citing its Gothic-style stone and brick buildings.[53][54] The facility had been shuttered three years earlier in 1990,[55] due to inhumane living conditions.[53]

The 15-acre reformatory, housing its own power plant and farm, was partially torn down shortly after filming was completed, leaving the main administration building and two cellblocks.[53] Several of the interior shots of the specialized prison facilities, such as the admittance rooms and the warden's office, were shot in the reformatory. The interior of the boarding room used by Brooks and Red was in the administration building; exterior shots of the boarding house were taken elsewhere. Internal scenes in the prison cellblocks were filmed on a sound stage built inside a nearby shuttered Westinghouse Electric factory. Since Darabont wanted the inmates' cells to face each other, almost all the cellblock scenes were shot on a purpose-built set housed in the Westinghouse factory,[53] except for the scene featuring Elmo Blatch's admission of guilt for the crimes for which Andy was convicted. It was filmed in one of the actual prison's more confined cells.[56] Scenes were also filmed in Mansfield, as well as neighboring Ashland, Ohio.[57] The oak tree under which Andy buries his letter to Red was located near Malabar Farm State Park, in Lucas, Ohio;[44] it was destroyed by winds in 2016.[58]

Just as a prison in Ohio stood in for a fictional one in Maine, the beach scene showing Andy and Red's reunion in Zihuatanejo, Mexico, was actually shot in the Caribbean on the island of Saint Croix, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands.[59] The beach at 'Zihuatanejo' is the Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge,[60] a protected area for leatherback sea turtles.[61] Scenes shot in Upper Sandusky included the prison wood shop scene where Red and his fellow inmates hear The Marriage of Figaro (the woodshop is now called the Shawshank Woodshop),[44] and the opening court scene which was shot at the Wyandot County Courthouse.[60] Other shooting locations included Pugh Cabin in Malabar Farm State Park, where Andy sits outside as his wife engages in an affair,[62] Butler, Ohio, stood in for Buxton, Maine,[63] and the Bissman Building in Mansfield served as the halfway house where Brooks stayed following his release.[64]

For the scene depicting Andy's escape from the prison, Darabont envisioned Andy using his miniature rock hammer to break into the sewage pipe, but he determined that this was not realistic. He opted instead to use a large piece of rock.[65] While the film portrays the iconic scene of Andy escaping to freedom through a sewer pipe described as a "river of shit", Robbins crawls through a mixture of water, chocolate syrup, and sawdust. The stream into which Robbins emerges was actually certified toxic by a chemist according to production designer Terence Marsh. The production team dammed the stream to make it deeper and used chlorination to partially decontaminate it.[49][65] Of the scene, Robbins said, "when you're doing a film, you want to be a good soldier—you don't want to be the one [who] gets in the way. So you will do things as an actor that are compromising to your physical health and safety."[66] The scene was intended to be much longer and more dramatic, detailing Andy's escape across a field and onto a train, but with only a single night available to film the sequence, it was shortened to showing Andy standing triumphant in the water.[65][67] Of his own work, Deakins considers the scene to be one of his least favorite, saying that he "over-lit" it.[67] In response, Darabont disagreed with Deakins' self-assessment. He said that the time and precision taken by Deakins, and their limited filming schedule, meant he had to be precise in what he could film and how. In a 2019 interview, he stated that he regretted that this meant he could not film a close up of Robbins' face as he climbed down out of the hole from his cell.[65]

As for the scene where Andy rebelliously plays music over the prison announcement system, it was Robbins' idea for Andy to turn the music up and not shut it off.[49] While in the finished film the inmates watch Rita Hayworth in Gilda (1946), they were originally intended to be watching Billy Wilder's The Lost Weekend (1945), a film about the dangers of alcohol. As the footage was too costly to procure from Paramount Pictures, producer Niki Marvin approached The Shawshank Redemption's domestic distribution rights-holder Columbia Pictures, which offered a list of lower-priced titles, one of which was Gilda.[68] As filming took place mainly in and around the prison, scenes were often shot in near chronological order respective of the different eras depicted throughout the story. This aided the actors' performances as their real-life relationships evolved alongside those of their respective characters.[65] Darabont commented that the scene in which Andy tells Red about his dreams of going to Mexico, was one of the last filmed and one that he most revisited in recollecting on the film's production. He praised Robbins and Freeman for completing the scene in only a few takes.[41]

Post-production

[edit]The final cut of the theatrically released film runs for 142 minutes,[1] and was dedicated to the memory of Allen Greene, Darabont's former agent, who died during filming from AIDS.[69] The film's first edit ran for nearly two and a half hours, which Glotzer considered "long", and several scenes were cut including a longer sequence of Red adjusting to life after incarceration; Darabont said that in test screenings the audience seemed to be getting impatient with the scene as they were already convinced that Red would not make it.[33] Another scene cut for time showed a prison guard investigating Andy's escape tunnel; this was thought to slow down the action.[70] The film originally had a cold open that played out Andy's crime, with his trial playing throughout the opening credits, but these scenes were edited together to create a more "punchy" opening.[71] One scripted scene, which Darabont described as his best work, was left unfilmed because of the shooting schedule.[72] In the scene, a dreaming Red is sucked into the poster of Rita Hayworth to find himself alone and insignificant on the Pacific shore, saying "I am terrified, there is no way home." Darabont said that he regretted being unable to capture the scene.[73]

In Darabont's original vision for the end of the film, Red is seen riding a bus towards the Mexican border, leaving his fate ambiguous. Glotzer insisted on including the scene of Red and Andy reuniting in Zihuatanejo. She said Darabont felt this was a "commercial, sappy" ending, but Glotzer wanted the audience to see them together.[8] Castle Rock agreed to finance filming for the scene without requiring its inclusion, guaranteeing Darabont the final decision.[74] The scene originally featured a longer reunion in which Andy and Red recited dialogue from their first meeting, but Darabont said it had a "golly-gee-ain't-we-cute" quality and excised it.[75] The beach reunion was test audiences' favorite scene; both Freeman and Robbins felt it provided the necessary closure. Darabont agreed to include the scene after seeing the test audience reactions, saying: "I think it's a magical and uplifting place for our characters to arrive at the end of their long saga..."[74]

Music

[edit]The film's score was composed by Thomas Newman. He felt that it already elicited such strong emotions without music that he found it difficult to compose one that would elevate scenes without distracting from them. The piece, "Shawshank Redemption", plays during Andy's escape from Shawshank and originally had a three-note motif, but Darabont felt it had too much of a "triumphal flourish" and asked that it be toned down to a single-note motif. "So Was Red", played following Red's release from prison, and leading to his discovery of Andy's cache, became one of Newman's favorite pieces. The piece was initially written for a solo oboe, until Newman reluctantly agreed to add harmonica—a reference to the harmonica Red receives from Andy to continue his message of hope. According to Darabont, harmonica player Tommy Morgan "casually delivered something dead-on perfect on the first take", and this is heard in the finished film.[76] Newman's score was so successful that excerpts from it were used in movie trailers for years afterwards.[36]

Release

[edit]Theatrical

[edit]Leading up to its release, the film was test screened with the public. These were described as "through the roof", and Glotzer said they were some of the best she had seen.[8][77] It was decided to mostly omit Stephen King's name from any advertising, as the studio wanted to attract a "more prestigious audience", who might reject a film from a writer known mostly for pulp fiction works such as The Shining and Cujo.[78]

Following early September premieres at the Renaissance Theatre in Mansfield, and the Toronto International Film Festival,[15][79] The Shawshank Redemption began a limited North American release on September 23, 1994. During its opening weekend, the film earned $727,000 from 33 theaters—an average of $22,040 per theater. Following a Hollywood tradition of visiting different theaters on opening night to see the audiences view their film live, Darabont and Glotzer went to the Cinerama Dome, but found no one there. Glotzer claimed that the pair actually sold two tickets outside the theater with the promise that if the buyers did not like the film, they could ask Castle Rock for a refund.[8] While critics praised the film, Glotzer believed that a lackluster review from the Los Angeles Times pushed crowds away.[8][77] It received a wide release on October 14, 1994, expanding to a total of 944 theaters to earn $2.4 million—an average of $2,545 per theater—finishing as the number-nine film of the weekend, behind sex-comedy Exit to Eden ($3 million), and just ahead of the historical drama Quiz Show ($2.1 million), which was in its fifth week at the cinemas.[36][51] The Shawshank Redemption closed in late November 1994, after 10 weeks with an approximate total gross of $16 million.[80] It was considered a box-office bomb, failing to recoup its $25 million budget, not including marketing costs and the cinema exhibitors' cuts.[8]

The film was also competing with Pulp Fiction ($108 million),[35] which also premiered October 14 following its Palme d'Or award win, and Forrest Gump ($330 million),[35] which was in the middle of a successful 42-week theatrical run.[77] Both films would become quotable cultural phenomena. A general audience trend towards action films starring the likes of Bruce Willis and Arnold Schwarzenegger was also considered to work against the commercial success of The Shawshank Redemption.[8] Freeman blamed the title, saying it was unmemorable,[8] while Robbins recalled fans asking: "What was that Shinkshonk Reduction thing?".[21] Several alternative titles had been posited before the release due to concerns that it was not a marketable title.[48] The low box office was also blamed on a lack of female characters to broaden the audience demographics, the general unpopularity of prison films, and the bleak tone used in its marketing.[21][41]

After being nominated for several Oscars in early 1995,[8] the film was re-released between February and March, earning a further $12 million.[80][41] In total, the film grossed $28.3 million in the United States and Canada,[51] and $45 million[81] from other markets for a worldwide total of $73.3 million. In the United States, it became the 51st-highest-grossing film of 1994, and the 21st-highest-grossing R-rated film of 1994.[51]

Post-theatrical

[edit]Despite its disappointing box-office returns, in what was then considered a risky move, Warner Home Video shipped 320,000 rental video copies throughout the United States in 1995. It went on to become the top rented film of that year.[36][82] Positive recommendations, repeat customer viewings, and being well received by both male and female audiences were considered key to the film's rental success.[21]

Ted Turner's Turner Broadcasting System had acquired Castle Rock Entertainment in 1993, which enabled his television channel, TNT, to obtain the cable-broadcast rights to the film.[35] According to Glotzer, because of the low box-office numbers, TNT could air the film at a very low cost, but still charge premium advertising rates. The film began airing regularly on the network in June 1997.[35][8] Television airings of the film accrued record-breaking numbers,[21] and its repeated broadcast was considered essential to turning the film into a cultural phenomenon after its poor box-office performance.[8] Darabont felt the turning point for the film's success was the Academy Award nominations, saying "nobody had heard of the movie, and that year on the Oscar broadcast, they were mentioning this movie seven times".[46] In 1996, the rights to The Shawshank Redemption were acquired by Warner Bros. Pictures, following the merger of its parent company Time Warner with the Turner Broadcasting System.[83]

In the United Kingdom, the film was watched by 1.11 million viewers on the subscription television channel Film4 in 2006, making it the year's second most-watched film on subscription digital television.[84]

By 2013, The Shawshank Redemption had aired on 15 basic cable networks, and in that year occupied 151 hours of airtime, rivaling Scarface (1983), and behind only Mrs. Doubtfire (1993). It was in the top 15% of movies among adults between the ages of 18 and 49 on the Spike, Up, Sundance TV, and Lifetime channels. Despite its mainly male cast, it was the most-watched movie on the female-targeted OWN network. In a 2014 Wall Street Journal article, based on the margins studios take from box office returns, home media sales, and television licensing, The Shawshank Redemption had made an estimated $100 million. Jeff Baker, then-executive vice president and general manager of Warner Bros. Home Entertainment, said that the home video sales had earned about $80 million.[35] While finances for licensing the film for television are unknown, in 2014, current and former Warner Bros. executives confirmed that it was one of the highest-valued assets in the studio's $1.5 billion library.[85] That same year, Gunton said that by its tenth anniversary in 2004, he was still earning six-figure residual payments, and was still earning a "substantial income" from it, which was considered unusual so many years after its release.[86]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]

The Shawshank Redemption opened to generally positive reviews.[90][91][92] Some reviewers compared the film to other well-received prison dramas, including Birdman of Alcatraz, Cool Hand Luke, and Riot in Cell Block 11.[93][94] Gene Siskel said that, like One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, The Shawshank Redemption is an inspirational drama about overcoming overbearing authority.[94] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[95]

Entertainment Weekly's Owen Gleiberman said that Freeman makes the Red character feel genuine and "lived-in".[5] Janet Maslin of The New York Times said that Freeman was quietly impressive, but lamented that Red's role in the film had limited range, restricted to observing Andy. She considered Freeman's commanding performance made him a much stronger figure than simply an observer. Maslin said that Freeman's performance was especially moving when describing how dependent Red had become on living within the prison walls.[96] Variety's Leonard Klady suggested that Freeman had the "showier" role, allowing him "a grace and dignity that came naturally", without ever becoming banal,[87] and The Washington Post's Desson Howe called Freeman a "master" of comedic and poignant cadence.[97] Even Kenneth Turan's Los Angeles Times review, which Glotzer credited with derailing the film's box-office success, praised Freeman, saying his "effortless screen presence lends Shawshank the closest thing to credibility it can manage".[98]

Of Robbins' performance, Gleiberman said that in his "laconic-good-guy, neo-Gary Cooper role, [Robbins] is unable to make Andy connect with the audience".[5] Conversely, Maslin said that Andy has the more subdued role, but that Robbins portrays him intensely, and effectively depicts the character as he transitions from new prisoner to aged father figure,[96] and Klady stated that his "riveting, unfussy ... precise, honest, and seamless" performance anchors the film.[87] Howe said that while the character is "cheesily messianic" for easily charming everyone to his side, comparing him to "Forrest Gump goes to jail", Robbins exudes the perfect kind of innocence to sell the story.[97] The Hollywood Reporter stated that both Freeman and Robbins gave outstanding, layered performances that imbued their characters with individuality,[88] and Rolling Stone's Peter Travers said that the pair created something "undeniably powerful and moving".[93] Gunton and Brown were deemed by Klady as "extremely credible in their villainy",[87] while Howe countered that Gunton's warden was a clichéd character who extols religious virtues while having people murdered.[97]

Maslin called the film an impressive directorial debut that tells a gentle tale with a surprising amount of loving care,[96] while Klady said the only failings came when Darabont focused for too long on supporting characters, or embellished a secondary story.[87] The Hollywood Reporter said that both the directing and writing were crisp, while criticizing the film's long running time.[88] Klady said that the length and tone, while tempered by humor and unexpected events, would dampen the film's mainstream appeal, but the story offered a fascinating portrait of the innate humanity of the inmates.[87] Gleiberman disliked that the prisoners' crimes were overlooked to portray them more as good guys.[5] Turan similarly objected to what he perceived as extreme violence and rape scenes, and making most of the prisoners seem like a "bunch of swell and softhearted guys" to cast the prison experience in a "rosy glow".[98] Klady summarized the film as "estimable and haunting entertainment", comparing it to a rough diamond with small flaws,[87] but Howe criticized it for deviating with multiple subplots, and pandering by choosing to resolve the story with Andy and Red's reunion, rather than leaving the mystery.[97] Ebert noted that the story works because it is not about Andy as the hero, but how Red perceives him.[79]

Deakins' cinematography was roundly praised,[87] with The Hollywood Reporter calling it "foreboding" and "well-crafted",[88] and Travers saying "the everyday agonies of prison life are meticulously laid out ... you can almost feel the frustration and rage seeping into the skin of the inmates".[93] Gleiberman praised the choice of scenery, writing "the moss-dark, saturated images have a redolent sensuality; you feel as if you could reach out and touch the prison walls".[5] The Hollywood Reporter said of Newman's score, "at its best moments, alights with radiant textures and sprightly grace notes, nicely emblematic of the film's central theme",[88] and Klady described it as "the right balance between the somber and the absurd".[87]

Accolades

[edit]The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards in 1995, the most for a Stephen King film adaptation:[99] Best Picture (Marvin), Best Actor (Freeman), Best Adapted Screenplay (Darabont), Best Cinematography (Deakins), Best Film Editing (Richard Francis-Bruce), Best Sound (Robert J. Litt, Elliot Tyson, Michael Herbick, and Willie D. Burton),[100] and Best Original Score (Newman, his first Academy Award nomination).[76] It did not win in any category.[99] It received two Golden Globe Award nominations for Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture for Freeman, and Best Screenplay for Darabont.[101]

Robbins and Freeman were both nominated for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role at the inaugural Screen Actors Guild Awards in 1995.[102] Darabont was nominated for a Directors Guild of America award in 1994 for Best Director of a feature film,[103] and a Writers Guild of America Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.[104] Deakins won the American Society of Cinematographers award for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography,[89] while producer Niki Marvin was nominated for a 1994 Golden Laurel Award by the Producers Guild of America.[104]

Legacy

[edit]

Darabont later adapted and directed two other King stories, The Green Mile (1999) and The Mist (2007).[105] In a 2016 interview, King said that The Shawshank Redemption was his favorite adaptation of his work, alongside Stand by Me.[106]

The oak tree, under which Andy leaves a note for Red directing him to Zihuatanejo, became a symbol of hope for its role in the film, and is considered iconic.[58][107] In 2016, The New York Times reported that the tree attracted thousands of visitors annually.[108] The tree was partially destroyed on July 29, 2011, when it was split by lightning, and news of the damage was reported by U.S. and international publications.[107][109] The tree was completely felled by strong winds on or around July 22, 2016,[107] and its vestiges were cut down in April 2017.[110] The remains were turned into The Shawshank Redemption memorabilia, including rock hammers and magnets.[111]

The prison site, which was planned to be fully torn down after filming,[55][112] became a tourist attraction.[53] The Mansfield Reformatory Preservation Society, a group of enthusiasts of the film, purchased the building and site from Ohio for one dollar in 2000 and took up maintaining it as a historical landmark, both as its purpose as a prison and as the filming site.[55][113] A 2019 report estimated the attraction to be earning $16 million in annual revenue.[41] Many of the rooms and props remain there, including the false pipe through which Andy escapes,[55] and a portion of the oak tree from the finale, after it was damaged in 2011.[44] The surrounding area is also visited by fans, while local businesses market "Shawshanwiches" and Bundt cakes in the shape of the prison.[55] According to the Mansfield/Richland County Convention and Visitors Bureau (later renamed Destination Mansfield),[59] tourism in the area had increased every year since The Shawshank Redemption premiered, and in 2013 drew in 18,000 visitors and over $3 million to the local economy.[44] As of 2019, Destination Mansfield operates the Shawshank Trail, a series of 15 marked stops around locations related to the film across Mansfield, Ashland, Upper Sandusky, and St Croix. The trail earned $16.9 million in revenue in 2018.[59][114]

In late August 2014, a series of events was held in Mansfield to celebrate the film's 20th anniversary including a screening of the film at the Renaissance Theatre, a bus tour of certain filming locations, and a cocktail party at the reformatory. Cast from the film attended some of the events, including Gunton, Scott Mann, Renee Blaine, and James Kisicki.[15] The 25th anniversary was similarly celebrated in August 2019.[115] Guests included Darabont, Blaine, Mann, Gunton, Alfonso Freeman,[114] Bellows, Rolston, Claire Slemmer,[116] and Frank Medrano.[117] Darabont stated that only at this event, the first time he had returned to Mansfield, was he able to realize the lasting impact of the film, stating, "It is a very surreal feeling to be back all these years later and people are still talking about it."[112]

Critical reassessment

[edit]Contemporary review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an 89% approval rating from 140 critics, with an average rating of 8.20/10. The consensus reads, "Steeped in old-fashioned storytelling and given evergreen humanity by Morgan Freeman and Tim Robbins, The Shawshank Redemption chronicles the hardship of incarceration patiently enough to come by its uplift honestly."[118] The film also has a score of 82 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 21 critics indicating "universal acclaim".[119]

In 1999, film critic Roger Ebert listed Shawshank on his list of The Great Movies.[92] The American Film Institute ranked the film number 72 on its 2007 AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) list, outranking Forrest Gump (76) and Pulp Fiction (94).[120][121] It was also number 23 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers (2006) list charting inspiring films.[122]

In 2005, the Writers Guild of America listed Darabont's screenplay at number 22 on its list of the 101 greatest screenplays,[123] and in 2006, Film4 listed it number 13 on its list of 50 Films to See Before You Die.[124] In 2014, The Shawshank Redemption was named Hollywood's fourth-favorite film, based on a survey of 2,120 Hollywood-based entertainment industry members; entertainment lawyers skewed the most towards the film.[125] In 2017, The Daily Telegraph named it the 17th-best prison film ever made,[126] and USA Today listed it as one of the 50 best films of all time.[127] In 2019, GamesRadar+ listed its ending as one of the best of all time.[128]

The Shawshank Redemption appeared on several lists of the greatest films of the 1990s, by outlets including: Paste and NME (2012),[129][130] Complex (2013),[131] CHUD.com (2014),[132] MSN (2015),[133] TheWrap,[134] Maxim,[135] and Rolling Stone (all 2017).[136]

Cultural influence

[edit]In November 2014, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences celebrated the film's 20th anniversary with a special one-night screening at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater in Beverly Hills, California.[46] In 2015, the film was selected by the United States Library of Congress to be preserved in the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". Darabont responded: "I can think of no greater honor than for The Shawshank Redemption to be considered part of our country's cinematic legacy."[90] Variety said that the word "Shawshank" could be used to instantly convey images of a prison.[36]

The significant and enduring public appreciation for the film has often been difficult for critics to define.[90] In an interview, Freeman said, "About everywhere you go, people say, 'The Shawshank Redemption—greatest movie I ever saw'" and that such praise "Just comes out of them". Robbins said, "I swear to God, all over the world—all over the world—wherever I go, there are people who say, 'That movie changed my life'".[8] In a separate interview, Stephen King said, "If that isn't the best [adaptation of my works], it's one of the two or three best, and certainly, in moviegoers' minds, it's probably the best because it generally rates at the top of these surveys they have of movies. ... I never expected anything to happen with it."[137] In a 2014 Variety article, Robbins claimed that South African politician Nelson Mandela told him about his love for the film,[8] while it has been cited as a source of inspiration by several sportsmen including Jonny Wilkinson (UK), Agustín Pichot (Argentina), Al Charron (Canada), and Dan Lyle (USA),[138] and Sarah Ferguson, the Duchess of York.[139] Gunton said he had encountered fans in Morocco, Australia, South America,[140] Germany, France, and Bora Bora.[38] Director Steven Spielberg said that the film was "a chewing-gum movie—if you step on it, it sticks to your shoe".[40] Speaking on the film's 25th anniversary, Darabont said that older generations were sharing it with younger generations, contributing to its longevity.[41]

It has been the number-one film on IMDb's user-generated Top 250 since 2008, when it surpassed The Godfather, having remained at or near the top since the late 1990s.[8][78] In the United Kingdom, readers of Empire voted the film as the best of the 1990s, the greatest film of all time in 2006, and it placed number four on Empire's 2008 list of "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time" and their 2017 list of "The 100 Greatest Movies".[21][141][142][143] In March 2011, the film was voted by BBC Radio 1 and BBC Radio 1Xtra listeners as their favorite film of all time.[144] It regularly appears on Empire's top 100 films, was named the greatest film to not win the Academy Award for Best Picture in a 2013 poll by Sky UK (it lost to Forrest Gump),[145] and ranked as Britain's favorite film in a 2015 YouGov poll. When the British Film Institute analyzed the demographic breakdown of the YouGov poll, it noted that The Shawshank Redemption was not the top-ranked film in any group, but was the only film to appear in the top 15 of every age group, suggesting it is able to connect with every polled age group, unlike Pulp Fiction which fared better with younger voters, and Gone with the Wind (1939) with older voters.[77]

A 2017 poll conducted by Gatwick Airport also identified the film as the fourth-best to watch while in flight.[146] When English film critic Mark Kermode interviewed a host of United States moviegoers, they compared it to a "religious experience".[77] It was also voted as New Zealand's favorite film in a 2015 poll.[147] Lasting fan appreciation has led to it being considered one of the most beloved films of all time.[8][36][114][148][149]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "The Shawshank Redemption". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "'The Shawshank Redemption': 2 Pros and Countless Cons". Entertainment Weekly. September 30, 1994. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Hooke, Alexander (May–June 2014). "The Shawshank Redemption". Philosophy Now. Archived from the original on June 3, 2014. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "The Shawshank Redemption". TV Guide. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Gleiberman, Owen (September 23, 1994). "The Shawshank Redemption". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Nichol, John (November 2, 2015). "Interview: Actor William Sadler Talks Tales From The Crypt, Shawshank, The Mist And More". ComingSoon.net. CraveOnline. Archived from the original on November 3, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ Pritchard, Tom (October 29, 2017). "All The Easter Eggs and References Hiding in Thor: Ragnarok". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Heiderny, Margaret (September 22, 2014). "The Little-Known Story of How The Shawshank Redemption Became One of the Most Beloved Films of All Time". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ TSR 1993, 1h20m32s.

- ^ Devine, J.P. (July 14, 2017). "J.P. Devine MIFF Movie Review: 'The Shawshank Redemption'". Kennebec Journal. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ "Mark Rolston". Hollywood.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ McNaull, Courtney (June 1, 2017). "Shawshank Hustle back for third year". Mansfield News Journal. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ TSR 1993, 16m42s—19m05s.

- ^ Wilson, Sean (August 22, 2017). "The scariest Stephen King characters to stalk the screen". Cineworld. Archived from the original on November 4, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ a b c Glaser, Susan (August 12, 2014). "'The Shawshank Redemption' 20 years later: Mansfield celebrates its role in the classic film". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ Whitmire, Lou (March 25, 2019). "Tickets available for events celebrating 25th anniversary of 'Shawshank'". Mansfield News Journal. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 30.

- ^ Kermode 2003, pp. 31, 39.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f Kermode, Mark (August 22, 2004). "Hope springs eternal". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 39.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 48.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Kermode 2003, p. 68.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 80.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (September 23, 1994). "Review: The Shawshank Redemption". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 69.

- ^ Morehouse, Isaac M. (October 3, 2008). "Stop Worrying about the Election". Ludwig von Mises Institute. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 37.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 41.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Nordyke, Kimberly (November 19, 2014). "'Shawshank Redemption' Reunion: Stars Share Funny Tales of "Cow Shit," Cut Scenes and that Unwieldy Title". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d e f Adams, Russell (May 22, 2014). "The Shawshank Residuals". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Chernov, Matthew (September 22, 2014). "'The Shawshank Redemption' at 20: How It Went From Bomb to Beloved". Variety. Archived from the original on September 23, 2014. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "20 Things You (Probably) Didn't Know About The Shawshank Redemption". ShortList. October 20, 2014. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c Voisin, Scott. "Character King Bob Gunton on The Shawshank Redemption". Phantom of the Movies' Videoscope. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Kermode 2003, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f Schulz, Bill (August 27, 2014). "20 Things You Didn't Know About 'The Shawshank Redemption'". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Boucher, Geoff (December 27, 2019). "'The Shawshank Redemption' At 25: Frank Darabont's Great Escape – Q&A". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 4, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c Lacher, Irene (October 5, 1994). "The Prize: Directing 'Shawshank': Frank Darabont Didn't Want to Just Write the Screenplay, So He Took a Pay Cut". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved September 29, 2017.

- ^ Hutchinson, Sean (September 24, 2015). "15 Things You Might Not Know About The Shawshank Redemption". MSN. Archived from the original on November 4, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Turner, Cory (August 7, 2014). "Visiting 'Shawshank' Sites, 20 Years Later". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- ^ a b "15 Things You Didn't Know About The Shawshank Redemption". Cosmopolitan. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved October 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c King, Susan (November 16, 2014). "Classic Hollywood Reconnecting with 'The Shawshank Redemption'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ TRF 2001, 22:42.

- ^ a b Harris, Will (July 5, 2015). "William Sadler on Freedom, naked tai chi, and getting silly as the Grim Reaper". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c Emery, Mark (September 23, 2015). "'The Shawshank Redemption': 10 fun facts about the movie 21 years after its release". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ Forgione, Mary (July 9, 2014). "'Shawshank Redemption' at 20? Ohio prison, film sites plan events". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "The Shawshank Redemption (1994)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Frook, John Evan (March 24, 1993). "Location News; Mexico's Cine South looks to branch out". Variety. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Cleveland: The Shawshank Redemption prison". The A.V. Club. March 8, 2011. Archived from the original on September 14, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- ^ a b Rauzi, Robin (December 1, 1993). "Doing 'Redemption' Time in a Former Prison". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Turner, Cory (August 4, 2011). "On Location: Mansfield, Ohio's 'Shawshank' Industry". All Things Considered. NPR. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ Valero, Gerardo (June 6, 2016). "The "Shawshank" Greatness, Part II". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ Kubacki, Dan (August 23, 2014). "Locals celebrate 20th anniversary of 'Shawshank' release with eventful weekend". Times-Gazette. Hillsboro, Ohio. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Smith, Nigel (July 25, 2016). "Rotten luck: tree from The Shawshank Redemption toppled by strong winds". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Shawshank Trail adds 15th stop in Virgin Islands". USA Today. McLean, Virginia. March 15, 2017. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Stephens, Steve (September 3, 2017). "Ticket to Write: 'Shawshank' scene to be marked on St. Croix". The Columbus Dispatch. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ "Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge (St. Croix)". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ "Pugh Cabin at Malabar Farm State Park". Shawshank Trail. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ "Snyder Road and Hagerman Road in Butler, Ohio". Shawshank Trail. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ "The Bissman Building". Shawshank Trail. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Bennett, Tara (December 25, 2019). "The Shawshank Redemption at 25: The Story Behind Andy's Iconic Prison Escape". IGN. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 75.

- ^ a b Shepherd, Jack; Crowther, Jane (October 18, 2019). "Roger Deakins on iconic Shawshank Redemption shot: "That's one of those ones that I hate"". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on October 18, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ Kermode 2003, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Gonzalez, Ed (October 16, 2004). "The Shawshank Redemption". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ Greene, Andy (July 30, 2015). "Flashback: Watch Two Cut Scenes From 'Shawshank Redemption'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ^ Kermode 2003, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Kermode 2003, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 79.

- ^ a b Kermode 2003, p. 87.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 86.

- ^ a b Adams, Russell (June 20, 2014). "How Thomas Newman Scored 'The Shawshank Redemption'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Callaghan, Paul (September 22, 2017). "How The Shawshank Redemption became the internet's favourite film". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Dowd, A.A. (August 19, 2014). "Escape is the unlikely link between The Shawshank Redemption and Natural Born Killers". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (October 17, 1999). "The Shawshank Redemption". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Shawshank Redemption (1994) – Weekend Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ Klady, Leonard (February 19, 1996). "B.O. with a vengeance: $9.1 billion worldwide". Variety. p. 1.

- ^ "Top Video Rentals" (PDF). Billboard. January 6, 1996. p. 54.

- ^ Cox, Dan (December 6, 1997). "Castle Rock near split-rights deal". Variety. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "Statistical Yearbook 2006/2007" (PDF). UK Film Council. p. 126. Retrieved April 21, 2022 – via British Film Institute.

- ^ Pallotta, Frank (May 28, 2014). "'The Shawshank Redemption' Accounted For A Huge Amount Of Cable Air Time In 2013". Business Insider. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ Weisman, Aly (June 4, 2014). "The Actors From 'Shawshank Redemption' Still Make A 'Steady' Income Off TV Residual Checks". Business Insider. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Klady, Leonard (September 9, 1994). "Review: 'The Shawshank Redemption'". Variety. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "'The Shawshank Redemption': THR's 1994 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. September 23, 1994. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "9th Annual ASC Awards – 1994". American Society of Cinematographers. 1994. Archived from the original on August 2, 2011. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c Barnes, Mike (December 16, 2015). "'Ghostbusters,' 'Top Gun,' 'Shawshank' Enter National Film Registry". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 19, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ^ Kirkland, Bruce (September 22, 2014). "The Shawshank Redemption: 20 years on, it's still a classic". Toronto Sun. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (October 17, 1999). "Great Movies: The Shawshank Redemption". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 11, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c Travers, Peter (September 23, 1994). "The Shawshank Redemption". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Siskel, Gene (September 23, 1994). "'The Shawshank Redemption' Unlocks A Journey To Freedom". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ "Find CinemaScore" (Type "Shawshank Redemption, The" in the search box). CinemaScore. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c Maslin, Janet (October 17, 1999). "Film Review; Prison Tale by Stephen King Told Gently, Believe It or Not". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Howe, Desson (September 23, 1994). "'The Shawshank Redemption' (R)". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Turan, Kenneth (September 23, 1994). "Movie Review : 'Shawshank': Solid Portrayals But A Dubious Treatment". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Best and Worst of Stephen King's Movies". MSN Movies. October 20, 2012. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "The 67th Academy Awards (1995) Nominees and Winners". Academy Awards. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

- ^ "The 52nd Annual Golden Globe Awards (1995)". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "The Inaugural Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild Awards. 1995. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ Dutka, Elaine (January 24, 1995). "DGA Nods: What's It Mean for the Oscars? : Movies: The surprising nominations of Frank Darabont ("Shawshank Redemption") and Mike Newell ("Four Weddings and a Funeral") may throw a twist into the Academy Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ a b "The Shawshank Redemption – Presented at The Great Digital Film Festival". Cineplex Entertainment. February 7, 2010. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ "The Shawshank Redemption". Academy Awards. November 18, 2014. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (February 2, 2016). "Stephen King On What Hollywood Owes Authors When Their Books Become Films: Q&A". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c Whitmire, Lou (July 22, 2016). "'Shawshank' tree falls over". Mansfield News Journal. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Victor, Daniel (July 25, 2016). "Famed Oak Tree From 'Shawshank Redemption' Is Toppled by Heavy Winds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 28, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ Child, Ben (August 3, 2011). "Shawshank Redemption tree split in half by storm". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on November 28, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ Martz, Linda (June 17, 2017). "Last of 'Shawshank Redemption' tree cut up". WKYC News. Archived from the original on November 28, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ "'Shawshank' oak tree merchandise for sale during 'Shawshank Hustle' in Mansfield". WKYC News. June 17, 2017. Archived from the original on November 28, 2017. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Bennett, Tara (September 25, 2019). "The Shawshank Redemption at 25: Frank Darabont on His Return to the Real Shawshank". IGN. Archived from the original on September 27, 2019. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ Glasser, Susan (July 21, 2019). "'Shawshank' 25th anniversary: How movie redeemed Mansfield's notorious Ohio State Reformatory". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c Pincus-Roth, Zachary (August 29, 2019). "The unlikely greatness of 'The Shawshank Redemption,' 25 years later". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ Brookbank, Sarah (March 8, 2019). "Shawshank Redemption cast to reunite in Mansfield for 25th anniversary". USA Today. McLean, Virginia. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ Schmidt, Ingrid (August 18, 2019). "Shawshank 25 - The Movie's Impact In Mansfield". WMFD News. Archived from the original on August 19, 2019. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ Tuggle, Zach (August 17, 2019). "Memories aplenty during Shawshank's 25th anniversary". Mansfield News Journal. Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ "The Shawshank Redemption". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "The Shawshank Redemption". Metacritic. September 18, 2017. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "America's Greatest Movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – 10th Anniversary Edition" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 6, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 16, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ "101 Greatest Screenplays". Writers Guild of America, West. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ "Film4's 50 Films To See Before You Die". Film4. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ "Hollywood's 100 Favorite Films". The Hollywood Reporter. June 25, 2014. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ Robey, Tim (July 23, 2017). "From Shawshank to Scum: the 20 best prison movies ever made". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ "50 best movies of all time". USA Today. McLean, Virginia. December 23, 2017. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Edwards, Rich (August 15, 2019). "The 25 best movie endings of all time, from Casablanca to Avengers: Infinity War". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ Dunaway, Michael (July 10, 2012). "The 90 Best Movies of the 1990s". Paste. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ Nicholls, Owen (May 15, 2012). "9 Best Films Of The 90s". NME. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ "The 50 Best Movies of the '90s". Complex. June 22, 2013. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ Nunziata, Nick (December 29, 2014). "The 100 Best Movies Ever – The Shawshank Redemption (#4)". CHUD.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ Horner, Rachel (April 3, 2017). "Top 50 Movies From the '90s". MSN. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ Welk, Brian (July 13, 2017). "90 Best Movies of the '90s, From 'The Silence of the Lambs' to 'The Matrix' (Photos)". TheWrap. Archived from the original on January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ Sciarrino, John (April 3, 2017). "The 30 Greatest Movies Of The '90S, Ranked". Maxim. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel; et al. (July 12, 2017). "The 100 Greatest Movies of the Nineties". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 30, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ Branch, Chris (September 24, 2014). "Stephen King Thought The 'Shawshank Redemption' Screenplay Was 'Too Talky'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on July 16, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ Gilbey, Ryan (September 26, 2004). "Film: Why are we still so captivated?". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Kermode 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Harris, Will (June 20, 2015). "Bob Gunton on Daredevil, Greg The Bunny, and The Shawshank Redemption". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- ^ "Shawshank is 'best ever film'". London Evening Standard. January 27, 2006. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. 2008. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movies". Empire. June 23, 2017. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ "Your favourite movies!". BBC Radio 1. March 10, 2011. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- ^ "Shawshank Redemption voted 'best Oscars also-ran'". The Independent. London. February 8, 2013. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ Morgan Britton, Luke (September 18, 2017). "Top 10 films to watch on a flight revealed". NME. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ^ Nordyke, Kimberly (July 2, 2015). "New Zealand's favourite film is The Shawshank Redemption". Stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (October 15, 2019). "Tim Robbins Blames 'Shawshank' Box Office Flop on Title No One Could Remember". IndieWire. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ Yenisey, Zeynep (September 10, 2019). "25 Facts About 'the Shawshank Redemption' You Probably Didn't Know". Maxim. Archived from the original on September 11, 2019. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

Works cited

[edit]- Frank Darabont (director, writer), Niki Marvin (producer) (September 23, 1994). The Shawshank Redemption (DVD). United States: Warner Home Video.

- Mark Kermode (writer), Andrew Abbott (director) (September 8, 2001). Shawshank: The Redeeming Feature (video).

- Kermode, Mark (2003). The Shawshank Redemption. BFI Modern Classics. London: British Film Institute. ISBN 978-0-8517-0968-0.

External links

[edit]- The Shawshank Redemption at IMDb

- The Shawshank Redemption at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Shawshank Redemption at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Shawshank Redemption at the TCM Movie Database

| Films directed |

|

|---|---|

| Films written |

|

| TV series developed |

|

| International | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Other | |