| Part of a series on |

| Cannons |

|---|

|

Cetbang (originally known as bedil, also known as warastra or meriam coak) were cannons produced and used by the Majapahit Empire (1293–1527) and other kingdoms in the Indonesian archipelago. There are 2 main types of cetbang: the eastern-style cetbang which looks like a Chinese cannon and is loaded from the front, and the western-style cetbang which is shaped like a Turkish and Portuguese cannon, loaded from the back.[1]: 97–98

Etymology

[edit]The word "cetbang" is not found in old Javanese, it probably comes from the Chinese word chongtong (銃筒), which also influenced the Korean word 총통(chongtong).[1]: 93 The term "meriam coak" is from the Betawi language, it means "hollow cannon", referring to the breech.[2][3] It is also simply referred to as coak.[4]: 10

Cetbang in old Javanese is known as bedil.[1][5][6] It is also called a warastra, which is synonymous with bedil.[7]: 246 Warastra is an old Javanese word, it means magic arrow, powerful arrow, awesome arrow, or superior arrow.[8]: 108, 132

In Java, the term for cannon is called bedil,[9] but this term may refer to various types of firearms and gunpowder weapon, from small pistol to large siege guns. The term bedil comes from wedil (or wediyal) and wediluppu (or wediyuppu) in the Tamil language.[10] In its original form, these words refer to gunpowder blast and saltpeter, respectively. But after being absorbed into bedil in the Malay language, and in a number of other cultures in the archipelago, that Tamil vocabulary is used to refer to all types of weapons that use gunpowder. In Javanese and Balinese the term bedil and bedhil is known, in Sundanese the term is bedil, in Batak it is known as bodil, in Makasarese, badili, in Buginese, balili, in Dayak language, badil, in Tagalog, baril, in Bisayan, bádil, in Bikol languages, badil, and Malay people call it badel or bedil.[10][11][12]

Description

[edit]There are 2 main types of cetbang:

Eastern-style cetbang

[edit]

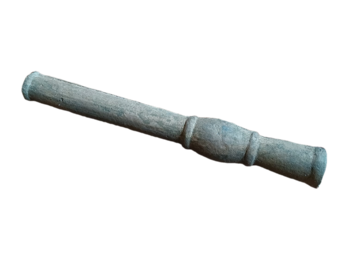

Its predecessors were brought by the Mongol-Chinese troops to Java, so they resembled Chinese cannons and hand cannons. Eastern-style cetbangs were mostly made of bronze and were front-loaded cannons. It fires arrow-like projectiles, but round bullets and co-viative projectiles[note 1] can also be used. These arrows can be solid-tipped without explosives, or with explosives and incendiary materials placed behind the tip. Near the rear, there is a combustion chamber or room, which refers to the bulging part near the rear of the gun, where the gunpowder is placed. The cetbang is mounted on a fixed mount, or as a hand cannon mounted on the end of a pole. There is a tube-like section on the back of the cannon. In the hand cannon-type cetbang, this tube is used as a socket for a pole.[1]: 94 The arrow-throwing cetbang would have been useful in naval combat, especially as a weapon used against ships (mounted under the bow gun shield or apilan), and also in a siege, because of its projectile ability to explode and as incendiary material.[1]: 97

Western-style cetbang

[edit]

The western-style cetbang was derived from the Turkish prangi cannon that came to the archipelago after 1460 CE. Just like prangi, this cetbang is a breech-loading swivel gun made of bronze or iron, firing single rounds or scatter shots (a large number of small bullets). In order to achieve a high firing rate, 5 chambers can be alternately reloaded.[1]: 94–95, 98

For the rear-loading cetbang, the smallest may be about 60 cm (24 in) long, and the largest about 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in). Their calibers range from 22 to 70 cm (8.7 to 27.6 in).[1]: 97 They are light, mobile cannons, most of them can be carried and shot by one man,[13]: 505 but they are not fired from the shoulder like a bazooka because the high recoil force could break human bones.[1]: 97 These gun are mounted on swivel yoke (called cagak), the spike is fitted into holes or sockets in the bulwarks of a ship or the ramparts of a fort.[14] A tiller of wood is inserted to the back of the cannon with rattan, to enable it to be trained and aimed.[13]: 505

Cetbang can be mounted as a fixed gun, swivel gun, or placed in a wheeled carriage. Small-sized cetbang can be easily installed on small vessels called penjajap and lancaran. This gun is used as an anti-personnel weapon, not anti-ship. In this age, even to the 17th century, the Nusantaran soldiers fought on a platform called balai (see the picture of a ship below) and perform boarding actions. Loaded with scatter shots (grapeshot, case shot, or nails and stones) and fired at close range, the cetbang would have been effective at this type of fighting.[7]: 241 [15]: 162

History

[edit]Majapahit era (ca. 1300–1478)

[edit]

Cannons were introduced to Majapahit when Kublai Khan's Chinese army under the leadership of Ike Mese sought to invade Java in 1293. History of Yuan mentioned that the Mongol used a weapon called 炮 (Pào) against Daha forces.[16]: 1–2 [17][18]: 220 This weapon is interpreted differently by researchers, it may be a trebuchet that throws thunderclap bombs, firearms, cannons, or rockets. It is possible that the gunpowder weapons carried by the Mongol-Chinese troops amounted to more than 1 type.[1]: 97

Thomas Stamford Raffles wrote in The History of Java that in 1247 saka (1325 CE), cannons have been widely used in Java especially by the Majapahit. It is recorded that the small kingdoms in Java that sought the protection of Majapahit had to hand over their cannons to the Majapahit.[19]: 106 [20]: 61 Majapahit under Mahapatih (prime minister) Gajah Mada (in office 1331–1364) utilized gunpowder technology obtained from Yuan dynasty for use in the naval fleet.[21]: 57

The neighboring kingdom of Sunda was recorded using bedil during the battle of Bubat of 1357. Kidung Sunda canto 2 stanza 87–95 mentioned that the Sundanese had juru-modya ning bedil besar ing bahitra (aimer/operator of the big cannon on the ships) in the river near Bubat square. Majapahit troops situated close to the river were unlucky: The corpses could hardly be called corpses, they were maimed, torn apart in the most gruesome way, the arms and the heads were thrown away. The cannonballs were said to discharge like rain, which forced the Majapahit troops to retreat in the first part of the battle.[22]: 34, 104–105

Ma Huan (Zheng He's translator) visited Java in 1413 and took notes about the local customs. His book, Yingya Shenlan, mentioned that cannons are fired in Javanese marriage ceremonies when the husband was escorting his new wife to the marital home to the sound of gongs, drums, and firecrackers.[7]: 245 Haiguo Guangji (海国广记) and Shuyu zhouzi lu (殊域周咨錄) recorded that Java is vast and densely populated, and their armored soldiers and hand cannons (火銃—huǒ chòng) dominated the Eastern Seas.[23]: 755 [24][25]

Because of the close maritime relations of the Nusantara archipelago with the territory of west India, after 1460 new types of gunpowder weapons entered the archipelago through Arab intermediaries. This weapon seems to be cannon and gun of Ottoman tradition, for example the prangi, which is a breech-loading swivel gun.[1]: 94–95

Majapahit decline and the rise of Islam (1478–1600)

[edit]

When the Portuguese first came to Malacca, they found a large colony of Javanese merchants under their own headmen; they were manufacturing their own cannon, which is deemed as important as sails in a ship.[26] Duarte Barbosa recorded the abundance of gunpowder-based weapons in Java ca. 1514. The Javanese were deemed as expert gun casters and good artillerymen. The weapon found there include one-pounder cannons, long muskets, spingarde (arquebus), schioppi (hand cannon), Greek fire, guns (cannons), and other fire-works.[27]: 254 [28]: 198 [29]: 224 When Malacca fell to the Portuguese in 1511 A.D., breech-loading swivel guns (cetbang) and muzzle-loading swivel guns (lela and rentaka) were found and captured by the Portuguese.[30]: 50 In 1513, the Javanese fleet led by Pati Unus, sailed to attack Portuguese Malacca "with much artillery made in Java, for the Javanese are skilled in founding and casting, and in all works in iron, exceeding what they have in India".[15]: 162 [31]: 23

De Barros and Faria e Sousa mention that with the fall of Malacca (1511), Albuquerque captured 3,000 out of 8,000 artillery. Among those, 2,000 were made from brass and the rest from iron, in the style of Portuguese berço (berso). All of the artillery had its proper complement of carriages which could not be rivaled even by Portugal.[29]: 279 [31]: 22 [32]: 127–128 Afonso de Albuquerque compared Malaccan gun founders as being on the same level as those of Germany. However, he did not state what ethnicity the Malaccan gun founder was.[32]: 128 [18]: 221 [33]: 4 Duarte Barbosa stated that the arquebus-maker of Malacca was Javanese.[34]: 69 The Javanese also manufactured their own cannon in Malacca.[26] Anthony Reid argued that the Javanese handled much of the productive work in Malacca before 1511 and in 17th century Pattani.[34]: 69

Wan Mohd Dasuki Wan Hasbullah explained several facts about the existence of gunpowder weapons in Malacca and other Malay states before the arrival of the Portuguese:[35]: 97–98

- No evidence showed that guns, cannons, and gunpowder are made in Malay states.

- No evidence showed that guns were ever used by the Malacca Sultanate before the Portuguese attack, even from Malay sources themselves.

- Based on the majority of cannons reported by the Portuguese, the Malays preferred small artillery.

The cannons found in Malacca were of various types: esmeril (1/4 to 1/2-pounder swivel gun,[36] probably refers to cetbang or lantaka), falconet (cast bronze swivel gun larger than the esmeril, 1 to 2-pounder,[36] probably refers to lela), medium saker (long cannon or culverin between a six and a ten-pounder, probably refers to meriam),[37][38]: 385 and bombard (short, fat, and heavy cannon).[30]: 46 The Malays also have 1 beautiful large cannon sent by the king of Calicut.[30]: 47 [31]: 22

Despite having a lot of artillery and firearms, the weapons of Malacca were mostly and mainly purchased from the Javanese and Gujarati, where the Javanese and Gujarati were the operators of the weapons. In the early 16th century, before the Portuguese arrival, the Malays were a people who lacked firearms. The Malay chronicle, Sejarah Melayu, mentioned that in 1509 they do not understand “why bullets killed”, indicating their unfamiliarity with using firearms in battle, if not in ceremony.[33]: 3 As recorded in Sejarah Melayu:

Setelah datang ke Melaka, maka bertemu, ditembaknya dengan meriam. Maka segala orang Melaka pun hairan, terkejut mendengar bunyi meriam itu. Katanya, "Bunyi apa ini, seperti guruh ini?". Maka meriam itu pun datanglah mengenai orang Melaka, ada yang putus lehernya, ada yang putus tangannya, ada yang panggal pahanya. Maka bertambahlah hairannya orang Melaka melihat fi'il bedil itu. Katanya: "Apa namanya senjata yang bulat itu maka dengan tajamnya maka ia membunuh?"

After (the Portuguese) came to Malacca, then met (each other), they shot (the city) with cannon. So all the people of Malacca were surprised, shocked to hear the sound of the cannon. They said, "What is this sound, like thunder?". Then the cannon came about the people of Malacca, some lost their necks, some lost their arms, some lost their thighs. The people of Malacca were even more astonished to see the effect of the gun. They said: "What is this weapon called that is round, yet is sharp enough to kill?" [39]: 254–255 [18]: 219

Lendas da India by Gaspar Correia and Asia Portuguesa by Manuel de Faria y Sousa confirmed Sejarah Melayu's account. Both recorded a similar story, although not as spectacular as described in Sejarah Melayu.[40]: 120–121 [41]: 43 The Epic of Hang Tuah narrates a Malaccan expedition to the country of Rum (the Ottoman Empire) to buy bedil (guns) and large meriam (cannons) after their first encounter with the Portuguese in 1509 CE, indicating their shortage of firearms and gunpowder weapons.[42]: 205–248 [note 2] Malaccan expedition to Rum (Ottoman Turks) to buy cannons never actually happened, it was only mentioned in the fictitious literature Hikayat Hang Tuah, which in reality based on the sending of a series of Acehnese embassies to the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century.[43]

When the Portuguese came to the archipelago, they referred to it as berço, which was also used to refer to any breech-loading swivel gun, while the Spaniards call it verso.[15]: 151

Colonial era (1600–1945)

[edit]When the Dutch captured Makassar's fort of Somba Opu (1669), they seized 33 large and small bronze cannons, 11 cast-iron cannons, 145 base (breech-loading swivel gun) and 83 breech-loading gun chamber, 60 muskets, 23 arquebuses, 127 musket barrels, and 8483 bullets.[38]: 384

Bronze breech-loading swivel guns, called ba'dili,[44][45] is brought by Makassan sailors on trepanging voyage to Australia. Matthew Flinders recorded the use of small cannon on board Makassan perahu off the Northern Territory in 1803.[46] Vosmaer (1839) writes that Makassan fishermen sometimes took their small cannon ashore to fortify the stockades they built near their processing camps to defend themselves against hostile Aborigines.[47] Dyer (ca. 1930) noted the use of cannon by Makassans, in particular the bronze breechloader with 2 inches (50.8 mm) bore.[48]: 64 [4]: 10

The Americans fought Moros equipped with breech-loading swivel guns in the Philippines in 1904.[13]: 505 These guns are usually referred to as lantaka or breech-loading lantaka.[49]

Surviving examples

[edit]There are surviving examples of the cetbang at:

- The Bali Museum, Denpasar, Bali. This Balinese cannon is located in the yard of Bali Museum.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. This cannon is thought to have been produced in the 15th century, made from bronze with a length of 37+7/16 inches (95.1 cm).[50]

- Luis de Camoes museum in Macau has a piece of highly ornamented cetbang. Year manufactured is unknown.

- Talaga Manggung museum, Majalengka, West Java. Numerous cetbang is in good condition due to routine cleaning ritual.[51]

- Some cetbang can be found in National Museum of Anthropology at Manila.

- Fatahillah Museum has a meriam coak labelled as "Cirebon cannon", in a fixed, highly ornamented mount. The whole mount is 234 cm (92 in) in length, 76 cm (30 in) in width, and 79 cm (31 in) in height.[52]

- Several examples and parts of cetbang can be found in Rijksmuseum, Netherlands, labelled as lilla (lela cannon).

- A cetbang is found in Beruas river, Perak, in 1986. Now it is exhibited in Beruas museum.[53]

Cetbang are also found at:

- Dundee beach, Northern Territory, Australia, known as "Dundee Beach swivel gun". Researchers have concluded that this bronze swivel cannon is from the 1750, before James Cook's voyage to Australia.[54] Initially thought to be Portuguese cannon, researcher has concluded that it is likely originated from Makassar. There is nothing in its chemical composition, style, or form that matches Portuguese breech loading swivel guns.[4]: 11

- Bissorang village, Selayar islands, Sulawesi Selatan province. This cannon is thought to have originated from the Majapahit era. Local people call this cetbang Ba'dili or Papporo Bissorang.[44][45]

- A Mataram-era (1587–1755) cetbang can be found at Lubuk Mas village, South Sumatera, Indonesia.[55]

- A 4-wheeled cetbang can be found at Istana Panembahan Matan in Mulia Kerta, West Kalimantan.[56]

- Two cannons can be found in Elpa Putih village, Amahai sub-district, Central Maluku Regency. It is thought to have originated from 16–17th century Javanese Islamic kingdoms.[57]

- Two cannons, named Ki Santomo and Nyi Santoni, can be found in Kasepuhan Palace (in Cirebon). They are labelled as "Meriam dari Mongolia" (cannon from Mongolia).[58] There is a doubt regarding the origin of the cannon, because the cannon is shaped like a Chinese dragon.[1]: 97

Gallery

[edit]-

Yuan-style Javanese hand cannon, likely manufactured locally in Java.

-

A hand cannon with carrying handle from Majapahit era.

-

A Chinese-style cannon found in Java, made of bronze and weighs about 15 kg. Unknown origin, it is either Chinese-made or a Javanese copy. It may be used as anti-ship cannon or as a mortar, firing large cannonballs or bombs.

-

A cetbang found on Selayar island

-

Cetbang in Bali Museum. Length: 1833 mm. Bore: 43 mm. Length of tiller: 315 mm. Widest part: 190 mm (at the base ring).

-

Bedil naga (dragon cannon) found on the Great Barrier Reef. Indonesian origin, manufactured between 1630 and 1680. Its discovery indicate that Asian vessels visited the coastline of eastern Australia prior to James Cook voyage.

-

A bronze sacred gun in Java, with breech-block, ca. 1866. Malay women come and settle accounts with the tutelary deity of this gun, and pray for children.

-

Breech-loading "lilla", Rijksmuseum, ca. 1750–1850. Length 180.5 cm, width 21.5 cm, calibre: 4.5 cm, weight: 120.8 kg.

-

Meriam coak dubbed "Cirebon cannon" of Jakarta History Museum (Fatahillah Museum).

-

Two cannons in Keraton Kasepuhan, labelled as cannon from Mongolia. The dragon head is similar to Chinese dragon (long) than Javanese dragon (naga).

Similar weapons

[edit]- Chongtong, Korean cannon adapted from the Yuan and Ming dynasty guns

- Bo-hiya, Japanese fire arrow

- Huochong, Chinese hand cannon

- Bedil tombak, Nusantaran hand cannon

See also

[edit]- Lantaka

- Breech-loading swivel gun

- Java arquebus, a type of firearm also called a bedil

- Timeline of the gunpowder age

- History of gunpowder

- History of cannon

Notes

[edit]- ^ A type of scatter bullet—when shot it spews fire, splinters and bullets, and can also be arrows. The characteristic of this projectile is that the bullet does not cover the entire bore of the barrel. Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 9 and 220.

- ^ Maka kata Laksamana, "Adapun hamba sekalian datang ini dititahkan oleh Sultan Melaka membawa surat dan bingkisan tanda berkasih-kasihan antara Sultan Melaka dan duli Sultan Rum, serta hendak membeli bedil dan meriam yang besar-besar. Adalah kekurangan sedikit bedil yang besar-besar di dalam negeri Melaka itu. Adapun hamba lihat tanah di atas angin ini terlalu banyak bedil yang besar-besar.”. Translation: Then the Admiral said, "As for our reason for coming here, we were ordered by the Sultan of Melaka to bring a letter and a gift of sympathy between the Sultan of Melaka and the Sultan of Rum, as well as to buy large guns and cannons. There is a shortage of large guns in the state of Melaka. While I see that the land above the wind has too many big guns."

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Averoes, Muhammad (2020). Antara Cerita dan Sejarah: Meriam Cetbang Majapahit. Jurnal Sejarah, 3(2), 89 - 100.

- ^ Museum Nasional (1985). Meriam-Meriam Kuno di Indonesia. Jakarta: Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

- ^ Singhawinata, Asep (27 March 2017). "Meriam Peninggalan Hindia Belanda". Museum Talagamanggung Online. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Clark, Paul (2013). Dundee Beach Swivel Gun: Provenance Report. Northern Territory Government Department of Arts and Museums.

- ^ "Mengejar Jejak Majapahit di Tanadoang Selayar - Semua Halaman - National Geographic". nationalgeographic.grid.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ Arthomoro (14 November 2019). "Mengenal Cetbang / Meriam Kerajaan Majapahit dari Jenis , Tipe dan Fungsinya". kompilasitutorial.com. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1976). "L'Artillerie legere nousantarienne: A propos de six canons conserves dans des collections portugaises" (PDF). Arts Asiatiques. 32: 233–268. doi:10.3406/arasi.1976.1103. S2CID 191565174.

- ^ Mardiwarsito, L. (1992). Kamus Indonesia-Jawa Kuno. Jakarta: Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

- ^ Gardner, G. B. (1936). Keris and Other Malay Weapons. Singapore: Progressive Publishing Company.

- ^ a b Kern, H. (January 1902). "Oorsprong van het Maleisch Woord Bedil". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 54: 311–312. doi:10.1163/22134379-90002058.

- ^ Syahri, Aswandi (6 August 2018). "Kitab Ilmu Bedil Melayu". Jantung Melayu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ Rahmawati, Siska (2016). "Peristilahan Persenjataan Tradisional Masyarakat Melayu di Kabupaten Sambas". Jurnal Pendidikan Dan Pembelajaran Khatulistiwa. 5.

- ^ a b c Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576077702.

- ^ "Cannons of the Malay Archipelago". www.acant.org.au. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Wade, Geoff; Tana, Li, eds. (2012). Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4311-96-0.

- ^ Schlegel, Gustaaf (1902). "On the Invention and Use of Fire-Arms and Gunpowder in China, Prior to the Arrival of European". T'oung Pao. 3: 1–11.

- ^ Lombard, Denys (1990). Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale (The Javanese Crossroads: Towards a Global History) Vol. 2. Paris: Editions de l'Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales. Page 178.

- ^ a b c Reid, Anthony (1993). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680. Volume Two: Expansion and Crisis. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- ^ Raffles, Thomas Stamford (1830). The History of Java. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street.

- ^ Yusof, Hasanuddin (September 2019). "Kedah Cannons Kept in Wat Phra Mahathat Woramahawihan, Nakhon Si Thammarat". Jurnal Arkeologi Malaysia. 32: 59–75.

- ^ Pramono, Djoko (2005). Budaya Bahari. Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 9789792213768.

- ^ Berg, C. C., 1927, Kidung Sunda. Inleiding, tekst, vertaling en aanteekeningen, BKI LXXXIII : 1-161.

- ^ Hesheng, Zheng; Yijun, Zheng (1980). 郑和下西洋资料汇编 (A Compilation of Materials on Zheng He's Voyages to the West) Volume 2, Part 1. 齐鲁书社 (Qilu Publishing House).

《海国广记·爪哇制度》有文字,知星历。其国地广人稠,甲兵火铳为东洋诸番之雄。其俗尚气好斗,生子一岁,便以匕首佩之。刀极精巧,名日扒刺头,以金银象牙雕琢人鬼为靶。男子无老幼贫富皆佩,若有争置,即拔刀相刺,盖杀人当时拿获者抵死,逃三日而出,则不抵死矣。

- ^ Congjian, Yan (1583). 殊域周咨錄 (Shuyu Zhouzilu) 第八卷真臘 (Volume 8 Chenla). p. 111.

其國地廣人稠,甲兵火銃,為東洋諸番之雄。其俗尚氣好鬥。

- ^ Wenbin, Yan, ed. (2019). 南海文明圖譜:復原南海的歷史基因◆繁體中文版 (Map of South China Sea Civilization: Restoring the Historical Gene of the South China Sea. Traditional Chinese Version). Rúshì wénhuà. p. 70. ISBN 9789578784987.

《海國廣記》記載,爪哇「甲兵火銃為東洋諸蕃之冠」。

- ^ a b Furnivall, J. S. (2010). Netherlands India: A Study of Plural Economy. Cambridge University Press. p. 9.

- ^ Jones, John Winter (1863). The travels of Ludovico di Varthema in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India, and Ethiopia, A.D. 1503 to 1508. Hakluyt Society.

- ^ Stanley, Henry Edward John (1866). A Description of the Coasts of East Africa and Malabar in the Beginning of the Sixteenth Century by Duarte Barbosa. The Hakluyt Society.

- ^ a b Partington, J. R. (1999). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0.

- ^ a b c Charney, Michael (2004). Southeast Asian Warfare, 1300-1900. BRILL. ISBN 9789047406921.

- ^ a b c Crawfurd, John (1856). A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries. Bradbury and Evans.

- ^ a b Birch, Walter de Gray (1875). The Commentaries of the Great Afonso Dalboquerque, Second Viceroy of India, translated from the Portuguese edition of 1774 volume 3. London: The Hakluyt society.

- ^ a b Charney, Michael (2012). Iberians and Southeast Asians at War: the Violent First Encounter at Melaka in 1511 and After. In Waffen Wissen Wandel: Anpassung und Lernen in transkulturellen Erstkonflikten. Hamburger Edition.

- ^ a b Reid, Anthony (1989). The Organization of Production in the Pre-Colonial Southeast Asian Port City. In Broeze, Frank (Ed.), Brides of the Sea: Asian Port Cities in the Colonial Era (pp. 54–74). University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ Hasbullah, Wan Mohd Dasuki Wan (2020). Senjata Api Alam Melayu. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

- ^ a b Manucy, Albert C. (1949). Artillery Through the Ages: A Short Illustrated History of the Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America. U.S. Department of the Interior Washington. p. 34. ISBN 9780788107450.

- ^ Lettera di Giovanni Da Empoli, with introduction and notes by A. Bausani, Rome, 1970, page 138.

- ^ a b Tarling, Nicholas (1992). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: Volume 1, From Early Times to C.1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521355056.

- ^ Kheng, Cheah Boon (1998). Sejarah Melayu The Malay Annals MS RAFFLES No. 18 Edisi Rumi Baru/New Romanised Edition. Academic Art & Printing Services Sdn. Bhd.

- ^ . Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. 17. pp. 117–149. 1886 – via Wikisource. Cetbang at the Internet Archive

- ^ Pintado, M.J. (1993). Portuguese Documents on Malacca: 1509–1511. National Archives of Malaysia. ISBN 9789679120257.

- ^ Schap, Bot Genoot, ed. (2010). Hikayat Hang Tuah II. Jakarta: Pusat Bahasa. ISBN 978-979-069-058-5.

- ^ Braginsky, Vladimir (8 December 2012). "Co-opting the Rival Ca(n)non the Turkish Episode of Hikayat Hang Tuah". Malay Literature. 25 (2): 229–260. doi:10.37052/ml.25(2)no5. ISSN 0128-1186.

- ^ a b "kabarkami.com Is For Sale". www.kabarkami.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ a b Amiruddin, Andi Muhammad Ali (2017). Surga kecil Bonea Timur. Makassar: Pusaka Almaida. p. 15. ISBN 9786026253385.

- ^ Flinders, Matthew (1814). A Voyage to Terra Australis. London: G & W Nichol.

- ^ Vosmaer, J. N. (1839). "Korte beschrijving van het Zuid- Oostelijk schiereiland van Celebes, in het bijzonder van de Vosmaers-Baai of van Kendari". Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kusten en Wetenschapen. 17: 63–184.

- ^ Dyer, A. J. (1930). Unarmed Combat: An Australian Missionary Adventure. Edgar Bragg & Sons Pty. Ltd., printers 4-6 Baker Street Sydney.

- ^ "National Museum of the Philippines, Part III (Museum of the Filipino People)". Wandering Bakya. 15 August 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Cannon | Indonesia (Java) | Majapahit period (1296–1520) | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Museum Talaga Manggung-Dinas Pariwisata dan Kebudayaan Provinsi Jawa Barat". www.disparbud.jabarprov.go.id. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ "Museum Sejarah Jakarta". Rumah Belajar. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ Amran, A. Zahid (22 September 2018). "Kerajaan Melayu dulu dah guna senjata api berkualiti tinggi setaraf senjata buatan Jerman | SOSCILI". Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ La Canna, Xavier (22 May 2014). "Old cannon found in NT dates to 1750s". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Rawas, Sukandar. "Meriam kuno Lubuk Mas". Youtube.

- ^ Rodee, Ab (11 August 2017). "Meriam Melayu". Picbear. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Handoko, Wuri (July 2006). "Meriam Nusantara dari Negeri Elpa Putih, Tinjauan Awal atas Tipe, Fungsi, dan Daerah Asal". Kapata Arkeologi. 2: 68–87. doi:10.24832/kapata.v2i2.27. S2CID 186092709.

- ^ "Palace Kasepuhan-Dinas Pariwisata dan Kebudayaan Provinsi Jawa Barat". www.disparbud.jabarprov.go.id. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

Indonesian traditional weapons, armors, and premodern gunpowder-based weapons | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Filipino weapons | |

|---|---|

| Edged weapons | |

| Impact weapons | |

| Shields | |

| Flexible | |

| Pole or spear weapons | |

| Projectile |

|

| Firearms | |

| Associated martial arts | |