Ottonian art is a style in pre-romanesque German art, covering also some works from the Low Countries, northern Italy and eastern France. It was named by the art historian Hubert Janitschek after the Ottonian dynasty which ruled Germany and Northern Italy between 919 and 1024 under the kings Henry I, Otto I, Otto II, Otto III and Henry II.[1] With Ottonian architecture, it is a key component of the Ottonian Renaissance (circa 951–1024). However, the style neither began nor ended to neatly coincide with the rule of the dynasty. It emerged some decades into their rule and persisted past the Ottonian emperors into the reigns of the early Salian dynasty, which lacks an artistic "style label" of its own.[2] In the traditional scheme of art history, Ottonian art follows Carolingian art and precedes Romanesque art, though the transitions at both ends of the period are gradual rather than sudden. Like the former and unlike the latter, it was very largely a style restricted to a few of the small cities of the period, and important monasteries, as well as the court circles of the emperor and his leading vassals.

After the decline of the Carolingian Empire, the Holy Roman Empire was re-established under the Saxon Ottonian dynasty. From this emerged a renewed faith in the idea of Empire and a reformed Church, creating a period of heightened cultural and artistic fervour. It was in this atmosphere that masterpieces were created that fused the traditions from which Ottonian artists derived their inspiration: models of Late Antique, Carolingian, and Byzantine origin. Surviving Ottonian art is very largely religious, in the form of illuminated manuscripts and metalwork, and was produced in a small number of centres for a narrow range of patrons in the circle of the Imperial court, as well as important figures in the church. However much of it was designed for display to a wider public, especially of pilgrims.[3]

The style is generally grand and heavy, sometimes to excess, and initially less sophisticated than the Carolingian equivalents, with less direct influence from Byzantine art and less understanding of its classical models, but around 1000 a striking intensity and expressiveness emerge in many works, as "a solemn monumentality is combined with a vibrant inwardness, an unworldly, visionary quality with sharp attention to actuality, surface patterns of flowing lines and rich bright colours with passionate emotionalism".[4]

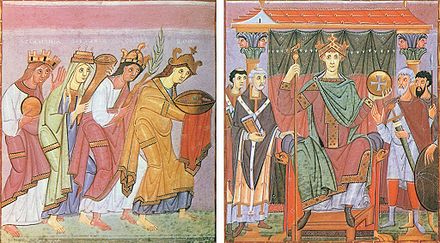

Following late Carolingian styles, "presentation portraits" of the patrons of manuscripts are very prominent in Ottonian art,[5] and much Ottonian art reflected the dynasty's desire to establish visually a link to the Christian rulers of Late Antiquity, such as Constantine, Theoderic, and Justinian as well as to their Carolingian predecessors, particularly Charlemagne. This goal was accomplished in various ways. For example, the many Ottonian ruler portraits typically include elements, such as province personifications, or representatives of the military and the Church flanking the emperor, with a lengthy imperial iconographical history.[6]

As well as the reuse of motifs from older imperial art, the removal of spolia from Late Antique structures in Rome and Ravenna and their incorporation into Ottonian buildings was a device intended to suggest imperial continuity. This was clearly the intention of Otto I when he removed columns, some of porphyry, and other building materials from the Palace of Theoderic in Ravenna and reused them in his new cathedral at Magdeburg. The one thing the ruler portraits rarely attempt is a close likeness of the individual features of a ruler; when Otto III died, some manuscript images of him were re-purposed as portraits of Henry II without the need being felt to change the features.

In a continuation and intensification of late Carolingian trends, many miniatures contain presentation miniatures depicting the donors of the manuscripts to a church, including bishops, abbots and abbesses, and also the emperor. In some cases successive miniatures show a kind of relay: in the Hornbach Sacramentary the scribe presents the book to his abbot, who presents it to St Pirmin, founder of Hornbach Abbey, who presents it to St Peter, who presents it to Christ, altogether taking up eight pages (with the facing illuminated tablets) to stress the unity and importance of the "command structure" binding church and state, on earth and in heaven.[7]

Byzantine art also remained an influence, especially with the marriage of the Greek princess Theophanu to Otto II, and imported Byzantine elements, especially enamels and ivories, are often incorporated into Ottonian metalwork such as book covers. However, if there were actual Greek artists working in Germany in the period, they have left less trace than their predecessors in Carolingian times. The manuscripts were both scribed and illuminated by monks with specialized skills,[8] some of whose names are preserved, but there is no evidence as to the artists who worked in metal, enamel and ivory, who are usually assumed to have been laymen,[9] though there were some monastic goldsmiths in the Early Medieval period, and some lay brothers and lay assistants employed by monasteries.[10] While secular jewellery supplied a steady stream of work for goldsmiths, ivory carving at this period was mainly for the church, and may have been centred in monasteries, although (see below) wall-paintings seems to have been usually done by laymen.

Ottonian monasteries produced many magnificent medieval illuminated manuscripts. They were a major art form of the time, and monasteries received direct sponsorship from emperors and bishops, having the best in equipment and talent available.[11] The range of heavily illuminated texts was very largely restricted (unlike in the Carolingian Renaissance) to the main liturgical books, with very few secular works being so treated.[2]

In contrast to manuscripts of other periods, it is very often possible to say with certainty who commissioned or received a manuscript, but not where it was made. Some manuscripts also include relatively extensive cycles of narrative art, such as the sixteen pages of the Codex Aureus of Echternach devoted to "strips" in three tiers with scenes from the life of Christ and his parables.[12] Heavily illuminated manuscripts were given rich treasure bindings and their pages were probably seen by very few; when they were carried in the grand processions of Ottonian churches it seems to have been with the book closed to display the cover.[13]

The Ottonian style did not produce surviving manuscripts from before about the 960s, when books known as the "Eburnant group" were made, perhaps at Lorsch, as several miniatures in the Gero Codex (now Darmstadt), the earliest and grandest of the group, copy those in the Carolingian Lorsch Gospels. This is the first stylistic group of the traditional "Reichenau school". The two other major manuscripts of the group are the sacramentaries named for Hornbach and Petershausen. In the group of four presentation miniatures in the former described above "we can almost follow ... the movement away from the expansive Carolingian idiom to the more sharply defined Ottonian one".[14]

A number of important manuscripts produced from this period onwards in a distinctive group of styles are usually attributed to the scriptorium of the island monastery of Reichenau in Lake Constance, despite an admitted lack of evidence connecting them to the monastery there. C. R. Dodwell was one of a number of dissident voices here, believing the works to have been produced at Lorsch and Trier instead.[15] Wherever it was located, the "Reichenau school" specialized in gospel books and other liturgical books, many of them, such as the Munich Gospels of Otto III (c. 1000) and the Pericopes of Henry II (Munich, Bayerische Nationalbibl. clm. 4452, c. 1001–1024), imperial commissions. Due to their exceptional quality, the manuscripts of Reichenau were in 2003 added to the UNESCO Memory of the World International Register.[16]

The most important "Reichenau school" manuscripts are agreed to fall into three distinct groups, all named after scribes whose names are recorded in their books.[17] The "Eburnant group" covered above was followed by the "Ruodprecht group" named after the scribe of the Egbert Psalter; Dodwell assigns this group to Trier. The Aachen Gospels of Otto III, also known as the Liuthar Gospels, give their name to the third "Liuthar group" of manuscripts, most from the 11th century, in a strongly contrasting style, though still attributed by most scholars to Reichenau, but by Dodwell also to Trier.[18]

The outstanding miniaturist of the "Ruodprecht group" was the so-called Master of the Registrum Gregorii, or Gregory Master, whose work looked back in some respects to Late Antique manuscript painting, and whose miniatures are notable for "their delicate sensibility to tonal grades and harmonies, their fine sense of compositional rhythms, their feelings for the relationship of figures in space, and above all their special touch of reticence and poise".[19] He worked chiefly in Trier in the 970s and 980s, and was responsible for several miniatures in the influential Codex Egberti, a gospel lectionary made for Archbishop Egbert of Trier, probably in the 980s. However, the majority of the 51 images in this book, which represent the first extensive cycle of images depicting the events of Christ's life in a western European manuscript, were made by two monks from Reichenau, who are named and depicted in one of the miniatures.[20]

The style of the "Liuthar group" is very different, and departs further from rather than returning to classical traditions; it "carried transcendentalism to an extreme", with "marked schematization of the forms and colours", "flattened form, conceptualized draperies and expansive gesture".[21] Backgrounds are often composed of bands of colour with a symbolic rather than naturalistic rationale, the size of figures reflects their importance, and in them "emphasis is not so much on movement as in gesture and glance", with narrative scenes "presented as a quasi-liturgical act, dialogues of divinity".[22] This gestural "dumb-show [was] soon to be conventionalized as a visual language throughout medieval Europe".[4]

The group were produced perhaps from the 990s to 1015 or later, and major manuscripts include the Munich Gospels of Otto III, the Bamberg Apocalypse and a volume of biblical commentary there, and the Pericopes of Henry II, the best known and most extreme of the group, where "the figure-style has become more monumental, more rarified and sublime, at the same time thin in density, insubstantial, mere silhouettes of colour against a shimmering void".[23] The group introduced the background of solid gold to Western illumination.

Two dedication miniatures added to the Egmond Gospels around 975 show a less accomplished Netherlandish version of Ottonian style. In Regensburg St. Emmeram's Abbey held the major Carolingian Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram, which probably influenced a style with "an incisive line and highly formal organization of the page", giving in the Uta Codex of c. 1020 complex schemes where "bands of gold outline the bold, squares circles, ellipses, and rhombs that enclose the figures", and inscriptions are incorporated in the design explicating its complex theological symbolism. This style was to be very influential on Romanesque art in several media.[24]

Echternach Abbey became important under Abbot Humbert, in office from 1028 to 1051, and the pages (as opposed to the cover) of the Codex Aureus of Echternach were produced there, followed by the Golden Gospels of Henry III in 1045–46, which Henry presented to Speyer Cathedral (now Escorial), the major work of the school. Henry also commissioned the Uppsala Gospels for the cathedral there (now in the university library).[25] Other important monastic scriptoria that flourished during the Ottonian age include those at Salzburg,[26] Hildesheim, Corvey, Fulda, and Cologne, where the Hitda Codex was made.[27]

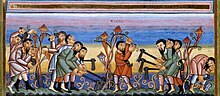

This scene was often included in Ottonian cycles of the Life of Christ. Many show Jesus (with crossed halo) twice, once asleep and once calming the storm.

Objects for decorating churches such as crosses, reliquaries, altar frontals and treasure bindings for books were all made of or covered by gold, embellished with gems, enamels, crystals, and cameos.[28] This was a much older style, but the Ottonian version has distinctive features, with very busy decoration of surfaces, often gems raised up from the main surface on little gold towers, accompanied by "beehive" projections in gold wire, and figurative reliefs in repoussé gold decorating areas between the bars of enamel and gem decoration. Relics were assuming increasing importance, sometimes political, in this period, and so increasingly rich reliquaries were made to hold them.[29] In such works the gems do not merely create an impression of richness, but served both to offer a foretaste of the bejewelled nature of the Celestial city, and particular types of gem were believed to have actual powerful properties in various "scientific", medical and magical respects, as set out in the popular lapidary books.[30] The few surviving pieces of secular jewellery are in similar styles, including the crown worn by Otto III as a child, which he presented to the Golden Madonna of Essen after he outgrew it.[31]

Examples of crux gemmata or processional crosses include an outstanding group in the Essen Cathedral Treasury; several abbesses of Essen Abbey were Ottonian princesses. The Cross of Otto and Mathilde, Cross of Mathilde and the Essen cross with large enamels were probably all given by Mathilde, Abbess of Essen (died 1011), and a fourth cross, the Theophanu Cross came some fifty years later.[32] The Cross of Lothair (Aachen) and Imperial Cross (Vienna) were imperial possessions; Vienna also has the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire. The book cover of the Codex Aureus of Echternach (Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg) is in a very comparable style.[33] Other major objects include a reliquary of St Andrew surmounted by a foot in Trier,[34] and gold altar frontals for the Palace Chapel, Aachen and Basel Cathedral (now in Paris).[35] The Palace Chapel also has the pulpit or Ambon of Henry II. The late Carolingian upper cover of the Lindau Gospels (Morgan Library, New York) and the Arnulf Ciborium in Munich were important forerunners of the style, from a few decades before and probably from the same workshop.[36]

Large objects in non-precious metals were also made, with the earliest surviving wheel chandeliers from the end of the period, a huge candelabra in Essen, and in particular a spectacular collection of ambitious large bronze works, and smaller silver ones, at Hildesheim Cathedral from the period of Bishop Bernward (died 1022), who was himself an artist, although his biographer was unusually honest in saying that he did not reach "the peaks of perfection". The most famous of these is the pair of church doors, the Bernward Doors, with biblical figure scenes in bronze relief, each cast in a single piece, where the powerfully simple compositions convey their meanings by emphatic gestures, in a way comparable to the Reichenau miniatures of the same period.[37] There is also a bronze column, the Bernward Column, 3.79 metres (12.4 ft) high, originally the base for a crucifix, cast in a single hollow piece. This unusual form is decorated with twenty-four scenes from the ministry of Jesus in a continuous strip winding round the column in the manner of Trajan's Column and other Roman examples.[38]

Around 980, Archbishop Egbert of Trier seems to have established the major Ottonian workshop producing cloisonné enamel in Germany, which is thought to have fulfilled orders for other centres, and after his death in 993 possibly moved to Essen. During this period the workshop followed Byzantine developments (of many decades earlier) by using the senkschmelz or "sunk enamel" technique in addition to the vollschmelz one already used. Small plaques with decorative motifs derived from plant forms continued to use vollschmelz, with enamel all over the plaque, while figures were now usually in senkschmelz, surrounded by a plain gold surface into which the outline of the figure had been recessed. The Essen cross with large enamels illustrated above shows both these techniques.[39]

Much very fine small-scale sculpture in ivory was made during the Ottonian period, with Milan probably a site if not the main centre, along with Trier and other German and French sites. There are many oblong panels with reliefs which once decorated book-covers, or still do, with the Crucifixion of Jesus as the most common subject. These and other subjects very largely continue Carolingian iconography, but in a very different style.[40]

A group of four Ottonian ivory situlae appear to represent a new departure for ivory carving in their form, and the type is hardly found after this period. Situlae were liturgical vessels used to hold holy water, and previously were usually of wood or bronze, straight-sided and with a handle. An aspergillum was dipped in the situla to collect water with which to sprinkle the congregation or other objects. However the four Ottonian examples from the 10th century are made from a whole section of elephant tusk, and are slightly larger in girth at their tops. All are richly carved with scenes and figures on different levels: the Basilewsky Situla of 920 in the Victoria & Albert Museum, decorated with scenes from the Life of Christ on two levels,[41] the "Situla of Gotofredo" of c. 980 in Milan Cathedral,[42] one in the Aachen Cathedral Treasury,[43] and one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[44] All came from the milieu of the Ottonian court: an inscription says that Archbishop Gotfredus presented the Milan example in anticipation of a visit by the Emperor,[45] also referred to in the London example which was possibly from the same workshop.[46] The latest and most lavish is the Aachen example, which is studded with jewels and shows an enthroned Emperor, surrounded by a pope and archbishops. This was probably made in Trier about 1000.[47]

Among various stylistic groups and putative workshops that can be detected, that responsible for pieces including the panel from the cover of the Codex Aureus of Echternach and two diptych wings now in Berlin (all illustrated below) produced particularly fine and distinctive work, perhaps in Trier, with "an astonishing perception of the human form ... [and] facility in handling the material".[48]

A very important group of plaques, now dispersed in several collections, were probably commissioned (perhaps by Otto I) for Magdeburg Cathedral and are called the Magdeburg Ivories, "Magdeburg plaques", the "plaques from the Magdeburg Antependium" or similar names. They were probably made in Milan in about 970, to decorate a large flat surface, though whether this was a door, an antependium or altar frontal, the cover of an exceptionally large book, a pulpit, or something else, has been much discussed. Each nearly square plaque measures about 13x12 cm, with a relief scene from the Life of Christ inside a plain flat frame; one plaque in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York has a "dedication" scene, where a crowned monarch presents Christ with a model church, usually taken to be Otto I with Magdeburg Cathedral. Altogether seventeen survive, probably fewer than half of the original set. The plaques include background areas fully cut through the ivory, which would presumably originally have been backed with gold. Apart from the spaces left beside buildings, these openwork elements include some that leave chequerboard or foliage patterns.[49] The style of the figures is described by Peter Lasko as "very heavy, stiff, and massive ... with extremely clear and flat treatment of drapery ... in simple but powerful compositions".[50]

Although it is clear from documentary records that many churches were decorated with extensive cycles of wall-painting, survivals are extremely rare, and more often than not fragmentary and in poor condition. Generally they lack evidence to help with dating such as donor portraits, and their date is often uncertain; many have been restored in the past, further complicating the matter. Most survivals are clustered in south Germany and around Fulda in Hesse; though there are also important examples from north Italy.[51] There is a record of bishop Gebhard of Constance hiring lay artists for a now vanished cycle at his newly foundation (983) of Petershausen Abbey, and laymen may have dominated the art of wall-painting, though perhaps sometimes working to designs by monastic illuminators. The artists seem to have been rather mobile: "at about the time of the Oberzell pictures there was an Italian wall-painter working in Germany, and a German one in England".[52]

The church of St George at Oberzell on Reichenau Island has the best-known surviving scheme, though much of the original work has been lost and the remaining paintings to the sides of the nave have suffered from time and restoration. The largest scenes show the miracles of Christ in a style that both shows specific Byzantine input in some elements, and a closeness to Reichenau manuscripts such as the Munich Gospels of Otto III; they are therefore usually dated around 980–1000. Indeed, the paintings are one of the foundations of the case for Reichenau Abbey as a major centre of manuscript painting.[53]

Very little wood carving has survived from the period, but the monumental painted figure of Christ on the Gero Cross (around 965–970, Cologne Cathedral) is one of the outstanding masterpieces of the period. Its traditional dating by the church, long thought to be implausibly early, was finally confirmed by dendrochronology.[54] The Golden Madonna of Essen (about 1000, Essen Cathedral, which was formerly the abbey) is a virtually unique survival of a type of object once found in many major churches. It is a smaller sculpture of the Virgin and Child, which is in wood which was covered with gesso and then thin gold sheet.[55] Monumental sculpture remained rare in the north, though there are more examples in Italy, such as the stucco reliefs on the ciborium of Sant' Ambrogio, Milan, and also on that in the Abbey of San Pietro al Monte, Civate, which relate to ivory carving of the same period,[56] the large silver cross of the Abbess Raingarda in the Basilica of San Michele Maggiore in Pavia[57] and some stone sculpture.

Surviving Ottonian works are very largely those in the care of the church which were kept and valued for their connections with either royal or church figures of the period. Very often the jewels in metalwork were pilfered or sold over the centuries, and many pieces now completely lack them, or have modern glass paste replacements. As from other periods, there are many more surviving ivory panels (whose material is usually hard to re-use) for book-covers than complete metalwork covers, and some thicker ivory panels were later re-carved from the back with a new relief.[58] Many objects mentioned in written sources have completely disappeared, and we probably now only have a tiny fraction of the original production of reliquaries and the like.[2] A number of pieces have major additions or changes made later in the Middle Ages or in later periods. Manuscripts that avoided major library fires have had the best chance of survival; the dangers facing wall-paintings are mentioned above. Most major objects remain in German collections, often still church libraries and treasuries.

The term "Ottonian art" was not coined until 1890, and the following decade saw the first serious studies of the period; for the next several decades the subject was dominated by German art historians mainly dealing with manuscripts,[59] apart from Adolph Goldschmidt's studies of ivories and sculpture in general. A number of exhibitions held in Germany in the years following World War II helped introduce the subject to a wider public and promote the understanding of art media other than manuscript illustrations. The 1950 Munich exhibition Ars Sacra ("sacred art" in Latin) devised this term for religious metalwork and the associated ivories and enamels, which was re-used by Peter Lasko in his book for the Pelican History of Art, the first survey of the subject written in English, as the usual art-historical term, the "minor arts", seemed unsuitable for this period, where they were, with manuscript miniatures, the most significant art forms.[60] In 2003 a reviewer noted that Ottonian manuscript illustration was a field "that is still significantly under-represented in English-language art-historical research".[61]