Santa Paula, California | |

|---|---|

|

Top: Thomas Aquinas College; Bottom: historic train depot (left) and downtown (right) | |

| Nickname: Citrus Capital of the World[1] | |

Location in Ventura County and the state of California | |

| Coordinates: 34°21′21″N 119°4′6″W / 34.35583°N 119.06833°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Ventura |

| Founded | 1872[2] |

| Incorporated | April 22, 1902[3] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Leslie Cornejo[4] |

| • State senator | Monique Limón (D)[5] |

| • Assemblymember | Gregg Hart (D)[5] |

| • U.S. rep. | Julia Brownley (D)[6] |

| Area | |

| • City | 5.69 sq mi (14.75 km2) |

| • Land | 5.53 sq mi (14.32 km2) |

| • Water | 0.16 sq mi (0.42 km2) 2.41% |

| Elevation | 279 ft (85 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 30,657 |

| • Density | 5,543.76/sq mi (2,081.00/km2) |

| • Metro | 823,318 |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 93060, 93061 |

| Area code | 805 |

| FIPS code | 06-70042 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 1652793, 2411826 |

| Website | spcity |

Santa Paula (Spanish for "St. Paula") is a city in Ventura County, California, United States. Situated amid the orchards of the Santa Clara River Valley, the city advertises itself to tourists as the "Citrus Capital of the World".[11] Santa Paula was one of the early centers of California's petroleum industry. The Union Oil Company Building, the founding headquarters of the Union Oil Company of California in 1890, now houses the California Oil Museum.[11] The population was 30,657 at the 2020 census, up from 29,321 at the 2010 census.

The area of what today is Santa Paula was inhabited by the Chumash, a Native American people, before the Spanish arrived. In 1769, the Spanish Portola expedition, first Europeans to see inland areas of California, came down the Santa Clara River Valley from the previous night's encampment near Fillmore and camped in the vicinity of Santa Paula on August 12, near one of the creeks coming into the valley from the north (most likely Santa Paula Creek). Fray Juan Crespi, a Franciscan missionary traveling with the expedition, had previously named the valley Cañada de Santa Clara. He noted that the party traveled about 9 to 10 miles (14 to 16 km) that day and camped near a large native village, which he named San Pedro Amoliano.[12] The site of the expedition's arrival has been designated California Historical Landmark No. 727.[13][note 1][note 2][14]

Franciscan missionaries, led by Father Junipero Serra, became active in the area after the founding of the San Buenaventura Mission and established an Asistencia; the town takes its name from the Catholic Saint Paula. Santa Paula is located on the 1843 Rancho Santa Paula y Saticoy Mexican land grant.

In 1872 Nathan Weston Blanchard purchased 2,700 acres (10.9 km2) and laid out the townsite. Considered the founder of the community, he planted seedling orange trees in 1874.[15][16] Several small oil companies owned by Wallace Hardison, Lyman Stewart and Thomas R. Bard were combined and became the Union Oil Company in 1890.[17][18]

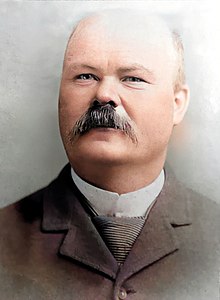

Santa Paula was incorporated in April 1902.[19] The first mayor was Lewis Arthur Hardison.[20]

In April 1911, Gaston Méliès moved his Star Film Company from San Antonio, Texas to a site just north of Santa Paula.[21]

The large South Mountain Oil Field southeast of town, just across the Santa Clara River, was discovered by the Oak Ridge Oil Company in 1916, and developed methodically through the 1920s, bringing further economic diversification and growth to the area. While the field peaked in production in the 1950s, Occidental Petroleum continues to extract oil through its Vintage Production subsidiary and remains a significant local employer.

A major expansion began in 2016 when construction started on a 500-acre (200 ha) master-planned community of 1,500 homes.[22]

The town has been devastated by floods, fires, and was once affected by a nearby truck explosion that resulted in an industrial disaster.

|

Main article: Great Flood of 1862 |

The Great Flood of 1862 began on December 24, 1861, when it rained for almost four weeks, reaching a total of 35 inches (890 mm) at Los Angeles.

|

Main article: St. Francis Dam § Collapse and flood wave |

The failure and near complete collapse of the St. Francis Dam took place in the middle of the night on March 12, 1928. The dam was holding a full reservoir of 12.4 billion gallons (47 billion liters) of water that surged down San Francisquito Canyon and emptied into the Santa Clara River. The town was first hit by the waters at approximately 3:00 a.m. Though hundreds of homes and structures were destroyed, the loss of life would have been greater if it were not for two motorcycle police officers that noisily warned as many people as possible.[23] A sculpture called "The Watchers" in downtown Santa Paula depicts this act of heroism.[24]

|

Main article: Thomas Fire |

In December 2017, the Thomas Fire broke out nearby. While it was the largest wildfire in modern California history at the time, the Santa Ana winds drove the fire toward Ventura and Santa Barbara. Over a thousand structures were destroyed which included a few out buildings just outside the city. It was finally confirmed to be fully contained in January 2018, and a reported 281,893 acres (440 sq mi; 114,078 ha) had burned. One firefighter and one civilian were the only fatalities directly caused by the fire. The cost of the fire rose to be an estimated $297 million.

|

Main article: Maria Fire |

On October 31, 2019, the Maria Fire was reported burning at the top of South Mountain between Santa Paula and Somis and expanded throughout that evening.[25] Heavily influenced by 20–30 mph (32–48 km/h) winds within the canyons, the fire became a full scale conflagration, growing from 50 to 750 acres (20 to 304 ha) inside an hour, to over 4,000 acres (16 km2) after several hours.[25][26] The fire worked its way north towards Santa Paula where the topography of the Santa Clara River Valley which can serve as a funnel for Santa Ana winds.[27] Mandatory evacuations were ordered for a wide swath of over 1,800 homes surrounding the fire area, affecting over 7,500 residences.[25][26]

|

Main article: Santa Clara Waste Water explosion |

A vacuum truck exploded at the Santa Clara Waste Water plant in the early morning hours of November 18, 2014. Two workers were injured in the initial explosion, three responding fire-fighters were injured by the fumes from the spill of a highly volatile chemical mixture, and 50 others were exposed to fumes and required treatment at local hospitals.[28][29] The driver was transporting waste from a temporary storage drum to a processing center when he stopped to take a meal break.[30] The rear of the truck exploded, spreading a white liquid over a 300-by-400-foot area (91 by 122 m) that spontaneously combusted as it dried and was sensitive to shock, pressure and the application of water or oxygen. The tires of the first fire truck on the scene and the boots of three firefighters sparked small explosions when they drove and walked over the substance as they went to help the injured workers.[31][32] The incident evolved into a disaster when later in the morning additional materials began to burn and explode, which resulted in a three-mile-long plume of toxic smoke (4.8 km) and the closing of Highway 126.[33] Chemical smoke drifted over the area and nearby residents and businesses were required to evacuate.[34]

About 1,000 US gallons (3,800 L; 830 imp gal) of a chemical mixture consisted of some sort of organic peroxide.[35] Three weeks after the incident, the substance was still highly susceptible to friction and seemed to react to something as slight as wind.[36] Sodium chlorite was identified in an internal investigation by the firm in the months following the disaster. They claimed that the chemical was being using as a water treatment agent for the first time and was stored in the same type of storage container as wastewater.[37][dead link] The worker combined the chemical with wastewater in the vacuum truck where the chemical interacting with organic material caused an explosion that blew off the back of the truck. A former county district attorney, retained by a company attorney, issued a report in March 2015 that provided an explanation of events indicating that the worker may have accidentally combined the chemicals.[37][38] Later, investigators found that an inspection by a Defense Logistics Agency contractor was scheduled for that morning and officials of the firm had directed the transfer of these hazardous materials to another location.[39]

Although the explosion and resulting fumes caused injuries including the lungs of three fire-fighters who remained off-duty indefinitely, the material scattered around the site was found to be non-hazardous for clean-up purposes.[40] The two fire engines that arrived first were scrapped. A local emergency was declared that lasted for three months.[41][38][42][43] The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency oversaw the decontamination of the site. The material was neutralized and solidified on site and taken to a landfill.[40]

On August 7, 2015, a Ventura County grand jury indicted the Santa Clara Waste Water Co., the affiliated Green Compass and nine company executives and managers.[44] Following the indictment, the district attorney had the nine defendants arrested on suspicion of several felonies and misdemeanors, including filing a false or forged instrument, dissuading a witness from reporting a crime, known failure to warn of serious concealed danger, withholding information regarding a substantial danger to public safety, conspiracy to commit a crime, causing impairment of an employee's body, and disposal of hazardous waste.[45] The individuals pleaded guilty. The two corporate entities reached an agreement in June 2019 after they had already paid about $800,000 in restitution.[46][44][47][48]

The city of Santa Paula, according to the United States Census Bureau, has a total area of 4.7 square miles (12 km2), 4.6 square miles (12 km2) of it land and 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2) of it (2.41%) water. Santa Paula is located in the Santa Clara River Valley on the north bank of the Santa Clara River and is surrounded by fruit orchards. The downtown area is centered around Main Street, which is home to the oldest homes in the city. Homes are often bungalows, cottages, Victorian-style houses and craftsman homes.[49][50]

Santa Paula has a warm-summer mediterranean climate (Csb) typical of the coastal Southern California with warm summers and cool winters.

| Climate data for Santa Paula, California, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1894–2008 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 97 (36) |

92 (33) |

98 (37) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

110 (43) |

108 (42) |

99 (37) |

99 (37) |

110 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 69.3 (20.7) |

69.2 (20.7) |

71 (22) |

74 (23) |

75.1 (23.9) |

77.2 (25.1) |

80.7 (27.1) |

82.7 (28.2) |

81.6 (27.6) |

78.5 (25.8) |

73.8 (23.2) |

69.2 (20.7) |

75.2 (24.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 55.2 (12.9) |

55.9 (13.3) |

57.5 (14.2) |

60 (16) |

62.5 (16.9) |

65.1 (18.4) |

68.8 (20.4) |

69.4 (20.8) |

68.1 (20.1) |

64.4 (18.0) |

59.1 (15.1) |

55.2 (12.9) |

61.8 (16.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 41.1 (5.1) |

42.5 (5.8) |

43.9 (6.6) |

45.9 (7.7) |

50 (10) |

53.1 (11.7) |

56.9 (13.8) |

56.1 (13.4) |

54.7 (12.6) |

50.2 (10.1) |

44.4 (6.9) |

41.1 (5.1) |

48.3 (9.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 20 (−7) |

23 (−5) |

25 (−4) |

30 (−1) |

35 (2) |

35 (2) |

38 (3) |

36 (2) |

40 (4) |

32 (0) |

28 (−2) |

22 (−6) |

20 (−7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.72 (94) |

4.85 (123) |

2.69 (68) |

0.83 (21) |

0.35 (8.9) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.01 (0.25) |

0.04 (1.0) |

0.16 (4.1) |

0.69 (18) |

1.44 (37) |

2.53 (64) |

17.38 (441) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.9 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 28.9 |

| Source 1: NOAA[51] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[52] | |||||||||||||

|

See also: California coastal sage and chaparral |

Bears can come down out of the hills and roam in neighboring agricultural areas and occasionally come into residential neighborhoods.[53][54] Mountain lions have periodically been spotted in residents' backyards.[55]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 188 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,047 | 456.9% | |

| 1910 | 2,216 | — | |

| 1920 | 3,967 | 79.0% | |

| 1930 | 7,452 | 87.8% | |

| 1940 | 8,986 | 20.6% | |

| 1950 | 11,049 | 23.0% | |

| 1960 | 13,279 | 20.2% | |

| 1970 | 18,001 | 35.6% | |

| 1980 | 20,658 | 14.8% | |

| 1990 | 25,062 | 21.3% | |

| 2000 | 28,598 | 14.1% | |

| 2010 | 29,321 | 2.5% | |

| 2020 | 30,675 | 4.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[56] | |||

The 2010 United States Census[57] reported that Santa Paula had a population of 29,321. The population density was 6,230.3 inhabitants per square mile (2,405.5/km2). The racial makeup of Santa Paula was 18,458 (63.0%) White, 152 (0.5%) African American, 460 (1.6%) Native American, 216 (0.7%) Asian, 24 (0.1%) Pacific Islander, 8,924 (30.4%) from other races, and 1,087 (3.7%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 23,299 persons (79.5%).

The Census reported that 29,188 people (99.5% of the population) lived in households, 44 (0.2%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 89 (0.3%) were institutionalized.

There were 8,347 households, out of which 4,087 (49.0%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 4,767 (57.1%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 1,267 (15.2%) had a female householder with no husband present, 650 (7.8%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 540 (6.5%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 45 (0.5%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 1,331 households (15.9%) were made up of individuals, and 678 (8.1%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.50. There were 6,684 families (80.1% of all households); the average family size was 3.85.

The population was spread out, with 8,722 people (29.7%) under the age of 18, 3,295 people (11.2%) aged 18 to 24, 8,012 people (27.3%) aged 25 to 44, 6,193 people (21.1%) aged 45 to 64, and 3,099 people (10.6%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31.1 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 101.5 males.

There were 8,749 housing units at an average density of 1,859.1 per square mile (717.8/km2), of which 4,694 (56.2%) were owner-occupied, and 3,653 (43.8%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.0%; the rental vacancy rate was 4.1%. 15,528 people (53.0% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 13,660 people (46.6%) lived in rental housing units.

As of the census of 2000, there were 28,598 people, 8,137 households, and 6,435 families residing in the city. The population density was 6,214.6 inhabitants per square mile (2,399.5/km2). There were 8,341 housing units at an average density of 1,812.6 per square mile (699.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 35.2% White, 5.41% African American, 1.02% Native American, 0.70% Asian, 0.19% Pacific Islander, .37% from other races, and 4.68% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 61.2% of the population.[58]

There were 8,136 households, out of which 44.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.1% were married couples living together, 13.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 20.9% were non-families. 17.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.49 and the average family size was 3.86.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 31.4% under the age of 18, 10.9% from 18 to 24, 29.7% from 25 to 44, 17.3% from 45 to 64, and 10.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females, there were 103.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 102.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $41,651, and the median income for a family was $45,419. Males had a median income of $32,165 versus $25,818 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,736. About 12.2% of families and 14.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.4% of those under age 18 and 9.1% of those age 65 or over.

While agriculture is the most important industry in Santa Paula today, the city experienced an economic boom after oil was discovered in 1880.[49]

The economy is primarily agriculturally based, originally focusing on the growing of oranges and lemons.[49] Santa Paula's mediterranean climate combined with an estimated 20 feet (6.1 m) of topsoil have made it a prime location for growing citrus. Avocado has also become a major crop and an avocado was added to the city's official seal. Calavo Growers, Inc. is headquartered here.[59]

Santa Paula has very few large retail stores but residents often travel to neighboring cities to purchase hard goods. The Main Street area consists mostly of clothing shops, specialty shops, novelty shops, dollar stores, restaurants, service-oriented businesses and office space. The city also has neighborhood stores and small grocery markets. Many of these small shops and markets have a distinct Latin-American flavor, often selling a myriad of imported items. In addition some markets also have a meat department which sells a variety of beef, poultry, and seafood.

A 501-acre expansion (203 ha) on the eastern edge of Santa Paula was approved in 2015. This residential and commercial development by Limoneira was known as "East Area One" for the purpose of approval. Officials and residents were hoping this major expansion of the city would create new jobs and increase tax revenue for the cash-strapped city.[60] When the project was first proposed in 1997, concerns were raised that Limoneira was beginning to develop their extensive holdings of prime farmland. Company officials claimed that 83% of the Teague-McKevett parcel was either unsuitable for agriculture or had a low value because of poor soil and drainage.[61]

The Santa Clara Valley represents one of the best preserved examples of a mature Southern California landscape of citrus groves.[16][62] Tourists find a town with a main street reminiscent of Middle America in an agricultural setting preserved through Ventura County's greenbelt agreements.[16] The California Oil Museum,[63] within the historic Union Oil building, is located downtown, as are the Santa Paula Art Museum[64] and Museum of Ventura County Agriculture Museum.[65] The Santa Paula Mural Project has completed numerous murals depicting the city's history.[66][67] The monogram "SP" on South Mountain above the city is visible from around town and along Highway 126. Students from Santa Paula High School first etched the letters into the hills in December 1922.[68]

The city changed from an at-large city council election to a district system on 2023 under the threat of a lawsuit under the California Voting Rights Act. The mayor's seat, which rotates among them, did not change.[69]

The Santa Paula Water Recycling Facility was built in 2010 for $63 million to treat the city sewage.[70] Santa Paula Water, a partnership of two corporations, financed, built and operated the facility under the agreement with the city. The city purchased the facility for $70.8 million in 2015 to take control and end a dispute over the failure of the plant to sufficiently remove chlorides. Although the new plant used modern treatment methods, the treated wastewater contained contaminants called chlorides that must be removed under state law before being discharged into the Santa Clara River.[71]

The Santa Paula Fire Department provided fire protection and emergency medical services at the basic life support level (BLS) from two fire stations. American Medical Response (AMR) is the paramedic ambulance provider for the city. On July 8, 2018, The Santa Paula Fire Department was disbanded after serving Santa Paula for 115 years. The Ventura County Fire Department now provides fire protection services for the City of Santa Paula. Both fire stations used by Santa Paula Fire were transferred to Ventura County Fire.[72]

The Santa Paula Police Department provides law enforcement services for the city. The overall crime rate is low.[49]

Historically, education was provided by the Santa Paula Elementary School District and the Santa Paula Union High School District. In 2013, the two bodies were merged to form the Santa Paula Unified School District. Many schools in Santa Paula, largely serving students from low-income families, are scoring low in state-administered tests, below the 30th percentile in statewide comparisons.[49]

Elementary schools

Middle school

High schools

Thomas Aquinas College, outside city limits

The city has been featured in Hollywood media on numerous occasions. Some examples include:

Various commercials, including a Super Bowl Budweiser commercial, (The Human Bridge) have been filmed in downtown Santa Paula.

Santa Paula was the early film capital of California. Gaston Méliès brought his Star Film Company to the city in 1911, filming movies such as The Ghost of Sulphur Mountain.

Parts of the movie Disorganized Crime (1989), starring Fred Gwynne, was filmed downtown on Main Street.

Main Street and other locations featured prominently in the 1990 Winona Ryder film Welcome Home, Roxy Carmichael. And other films such as “Pee-wee's Big Holiday”.

Chaplin (1992) filmed throughout the surrounding area and held a casting call in town for background actors.

Santa Paula also served as one of the locations for the motion picture Mr. Woodcock (2007), starring Billy Bob Thornton.

A good portion of Joe Dirt (2001) starring David Spade was filmed downtown as well as at the popular restaurant Mary B's.

The Lindsay Lohan movie Georgia Rule (2007) was filmed in Santa Paula.

The majority of the 1997 film Leave It to Beaver was filmed in Santa Paula, with many Santa Paula residents being cast in minor character roles and as extras. The famous scene of Beaver trapped in the giant coffee cup had Main Street blocked off for almost a week while filming continued.

Parts of the Brian De Palma movie Carrie (1976), starring Sissy Spacek, were filmed in Santa Paula.

Other movies that were filmed partially in Santa Paula include The Philadelphia Experiment (1984), the Chinatown sequel The Two Jakes (1990), the Martin Short/Danny Glover buddy comedy Pure Luck (1991), For Love of the Game (1999), Bubble Boy (2001), starring Jake Gyllenhaal, and Bedtime Stories (2008) starring Adam Sandler.

The James M. Sharp House is an historical Italian villa-style house built in 1890. It is located on West Telegraph Road, just outside Santa Paula, and has been the setting for several movies, including Amityville 4 (1989), The Black Gate (1995), and How to Make an American Quilt (1995).

The music video for “To Die For” by Sam Smith was shot entirely in the town.[78]

Dennis DeYoung, former lead singer of the popular 1970s and 1980s rock group Styx, filmed the music video for Desert Moon, also the title of his first solo album, at the train depot in 1984.

The music video for the 2001 song “Video” by American R&B artist India Arie was filmed in and around Santa Paula and its surrounding citrus groves. This was India Arie's debut song and video from her Acoustic Soul album.

Parts of the 1976 season 3 episode of The Rockford Files "Coulter City Wildcat", were filmed in Santa Paula.

On the television drama The West Wing, Santa Paula is the hometown of fictional presidential candidate Arnold Vinick (Alan Alda). In early 2005, Santa Paula Mayor Mary Ann Krause began a lobbying campaign to have Santa Paula declared Vinick's hometown. In a publicity move for the town, city officials officially "claim[ed] Senator Arnold Vinick as a resident of Santa Paula," in April 2005, and opened an official campaign headquarters for the fictional Republican Senator in the town's train depot. (Santa Paula for Vinick) On October 14, 2005, NBC released Vinick's official biography and revealed Santa Paula as the town in which he was raised.[79]

Santa Paula served as the backdrop for the fictional Charterville in the 1996–98 TV series Big Bad Beetleborgs.

An episode of the television series Matlock was filmed on Santa Paula St.

After a 1994 fire destroyed their sets in nearby Fillmore, the TV series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles filmed in various locations, including Santa Paula's Ebell Mansion.

The Santa Paula Train Depot has been a location for various productions, including for the miniseries The Thorn Birds (1983), starring Richard Chamberlain and in the season 3 finale of Glee (2012).

Scenes for the third season of Mayans M.C. were shot on Main Street in October 2020 and February 2021.[80]